Yehuda Amichai

Poems as Teachers | Episode 6

Being right may feel good, but what human price do we pay for this feeling of rightness? Yehuda Amichai’s poem “The Place Where We Are Right,” translated by Stephen Mitchell, asks us to answer this question, consider how doubt and love might expand and enrich our perspective, and reflect upon the buried and not-so-buried ruins of past conflicts, arguments, and wounds that still call for our attention.

This is the sixth episode of “Poems as Teachers,” a special seven-part miniseries on conflict and the human condition.

We’re pleased to offer Yehuda’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

Guests

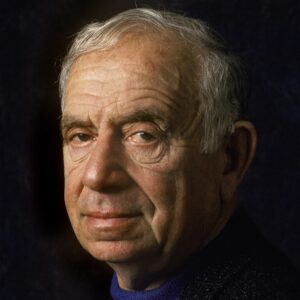

Yehuda Amichai was an Israeli poet and novelist born in Würzburg, Germany, and he lived from 1924 to 2000. His poetry is collected in numerous works, including Open Closed Open, The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai, and The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai.

Stephen Mitchell is an author, poet, and translator. His works of translation include The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, Gilgamesh, and Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon: Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda. Mitchell translated The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai with Chana Bloch. Image by Brie Childers.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and a number of years ago I was leading a community mediation in the north of Ireland. And in the context of the mediation, somebody said, The most frightening experience I ever had was 20 years ago when I spoke at a youth festival and people didn’t like what I said. As I was leaving, some of the young people gathered around my car and they thought it was being mild, but they were jostling the car and booing and jeering. And as this man said this, I thought, I think I was one of those young people and I asked him, Was this this festival, this date and this place? And he said, Yeah. And I’d had such a strong sense of connection with those other people. I was deepening my relationship with religion, deepening my relationship with some friends, and this guy had said something that people didn’t like, and I joined in, in this display of jeering that 20 years later was still something that somebody else said was the most frightening experience of their life. It was a shock to me, and it changed everything in that community mediation, for suddenly our past to be present in the room where we thought we were talking about what was happening now, but actually, we were talking about much more than that.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The Place Where We Are Right” by Yehuda Amichai translated by Stephen Mitchell

“From the place where we are right

flowers will never grow

in the spring.

“The place where we are right

is hard and trampled

like a yard.

“But doubts and loves

dig up the world

like a mole, a plow.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

where the ruined

house once stood.”

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

So this is one of Yehuda Amichai’s most famous poems. It’s so short and brilliant and precise. He is probably the most famous Israeli poet of the 20th century. He was born in 1924 and he died in 2000, and he was celebrated the world over. This particular translation is by Steven Mitchell. Yehuda Amichai’s poetry is characterized by a kind of style of language that takes really complex things and distills them into — not simplistic — but profoundly simple things. Graspable images and metaphors that can be used for deep reflection on personal life, on political life, on differences, on arguments, on change, on love, and you see this profoundly here.

If you read the poem, including the title by the end of it — and it’s such a short poem — you’ve said these words, “the place where we are right,” three times — in the title, in the first line, and then in the fourth line. “The place where we are right / flowers will never grow.” “The place where we are right / is hard and trampled.” So what is “the place [that] we are right” and what is the place of this title and this repeated refrain within the poem. And also what’s the emphasis? The “place” where we are right or the place where we are “right”? Or the emphasis on the “we”? You could go through those six words and place emphasis and find extraordinary riches and a harvest of reflection.

Partly what I think is so important in this is A) demonstrating the brilliance of Yehuda Amichai and Steven Mitchell’s translation. But B) that this is a poem, I think, that asks for reflection, to say, where is it that I think I’m right and how much work am I willing to do to reflect on the convenience of that, and to reflect on are there victims to the way that I think that I’m right? Are there victims created on the other side of that?

[music: “Creatures of Myth” by Gautam Srikishan]

The poem builds on the metaphor of land, “the place where we are right.” But then it goes alongside that there’s no flowers growing there in the spring, it’s “hard and trampled / like a yard.” And the place can be dug up “like a mole, a plow,” and then we also hear of the place “where the ruined / house once stood.” So we see a landscape, a landscape for growth, a landscape for animals, a landscape for harvest, and a landscape for living. How is it that we are able to use this land as a metaphor for reflection?

Yehuda Amichai had been born in Germany in 1924, like I said, and when he was 12, the family fled to Palestine. This was 1936. He’d grown up being called slurs in Germany, and told, because he was a Jew, to leave and go back to Palestine, and when they went, the same thing: told to leave.

And he fought in the Second World War, and he fought for the creation and protection of Israel. He knew the hatred with which Jews had been treated in Europe as century after century unfolded pogrom after pogrom. And the hatred that Israel faced, too.

He wasn’t a member of a political party, but he knew that poetry was political. And — like all those who love a thing best — he also wasn’t afraid of being critical. He said he was afraid though, “of people who speak in absolutes” — for him it’s a demonstration of loyalty to ask critical questions, as you see here in “doubts and loves / dig up the world,” the final stanza of this poem says. And it says, “but doubts and loves / dig up the world.” That “but” there is an indication of some kind of change, some turn.

How willing am I to allow both doubt and love to dig up the place where I’m right? Because to speak about the place where I’m right is to imply the place where other people are wrong. And there are things that I don’t want to be wrong about, hard-won things, but I always feel in Yehuda Amichai’s poem, what he’s doing is saying, Well, especially the place where it’s convenient for you to be right. That’s me projecting into it, totally. But he was so intelligent about conflict. I think he’s saying, In the place where you have privilege, or in the place where you’re frightened about acknowledging that you might be wrong, there, allow both doubt and love to dig that up because something else might be there. It isn’t to be groundless, it is to say that there might be another experience of land underneath your feet. It isn’t to say you don’t belong anywhere, leave, be gone. It is to say doubt and love are two things that can hold you. Love, alone, I don’t think is enough because it’s easy to love something and nonetheless be violent in its name. This is about saying “doubt and love.” The doubt that says, What if I need to pay attention to another point of view? How willing am I to ask myself a question that might mean that I have to stand on new ground, that I have to go a bit deeper, that I have to employ doubt and love and maybe even bring some of my loyalties into question in order to ask something that has a deeper integrity.

[music: “Taoudella” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’ve spent so much time thinking about those last three lines of the poem: “and a whisper will be heard in the place / where the ruined / house once stood.” Like if it was, “and a whisper will be heard in the place where the house once stood,” it would almost make sense to say, Oh, who lived there? But this is saying that the land has a memory of a ruin, and that ruin has a whisper.

What’s interesting is that it isn’t a shout that’ll be heard or it isn’t a voice, it’s a whisper, which is to say that you have to pay close attention.

I love the depth to which this is saying, there is history upon history upon history, and you need to know the story, the whispers from the ruins as well as what came before the ruins. Whose ruin is being referred to here? Everybody’s perhaps. The ruins of my own defensiveness; the ruins of my own rage; the ruins of the things that I refuse to acknowledge to be true, because I said, I’m willing to hurt this other grouping of people in order to justify the place where I’m right. These are the ruins that have whispers in them, he’s saying perhaps. These are the things that I need to listen to, but they’re buried.

He’s, in a certain sense, saying, dig up the ruins, let the ruins speak. You have something to learn. It’s a way of saying that the doubt that I had in myself of, Am I right? That there might’ve been something in there — in the context of the power that I had and the power of denial. He’s saying, you’re going to have to listen to that, and doubts and loves will be the thing that do it.

I love how trustable this is. He isn’t saying this is easy. This is not a poem that’s saying, Expose yourself to terrible harm or that says, where you’ve finally been able to make safety for yourself, go and make unsafety. What is being proposed, I think, is to say where it is that you have not been willing to examine the possibility that your power might be causing difficulty to people who are in the place that you say is wrong. You need to examine that power.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

So much of what we’re looking at in this series of poems as teachers, looking at conflict and the human condition, is about the possibility of change. And it’s always easy, I think, to think, well, the other person on the other side of this won’t change. And that might be true and understandable why you’d say that, you might’ve been given a little evidence. I always want to ask as well though other questions: Am I open to change? And this poem of Yehuda Amichai’s is a poem that considers the question of me being open to the possibility of change in myself, the possibility of a change in a way I think, a change in the way I think about my own doubts, my own loves, what it is that grounds me. How can I go deeper? How can I learn more? It’s not easy, but it is something that will cause a deeper sense of belonging if we can do it.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The Place Where We Are Right” by Yehuda Amichai translated by Steven Mitchell

“From the place where we are right

flowers will never grow

in the spring.

“The place where we are right

is hard and trampled

like a yard.

“But doubts and loves

dig up the world

like a mole, a plow.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

where the ruined

house once stood.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “The Place Where We Are Right” comes from Yehuda Amichai’s book The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai. Thank you to the University of California Press who gave us permission to use Yehuda’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Additional support for this mini-season of Poetry Unbound comes from:

Civic (Re)Solve — building communities of civic empowerment.

Quiet — listen and finish listening.

And The Hearthland Foundation — committed to justice, equity and connection, one creative act at a time.

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Cameron Musar, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.