Yu Xiuhua

Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You

How far would you go for great love? And what distances would you cross?

We’re pleased to offer Yu Xiuhua’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

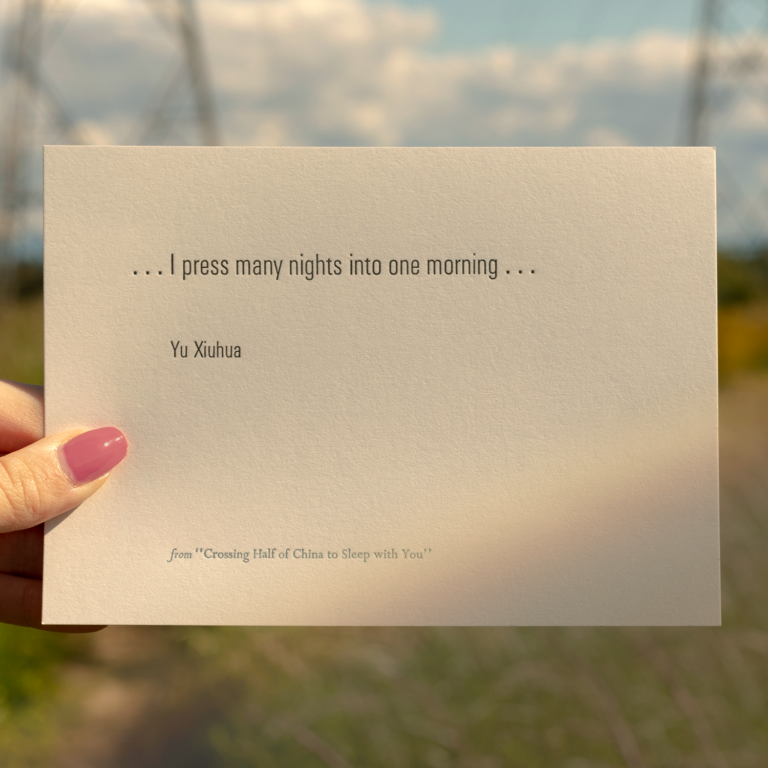

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Yu Xiuhua is a poet from Hengdian, in Hubei, China. She became well known in 2014 with her online poem “Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You.” In 2015, her debut book sold fifteen thousand copies in one day. The New York Times named her one of the eleven most courageous women around the world in 2017. Image: VCG / Getty Images

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Hi, friends. Pádraig here with a quick announcement before this final episode of this season: we will be back in September, with Season 6, and also in the autumntime, we have a Poetry Unbound book. More information about that coming at the end of this episode, so stay tuned for that, and in the meantime, thanks for listening.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and a question that I think can be really difficult to answer sometimes is, What do you want?, because What do you want? implies you only want one thing. But so often, hidden underneath a desire is another desire and another desire and another desire. Desire, I think, is a portal where we look at the thing we want, but we also look at the other things that are gathered around that. And I don’t think I know of any better vehicle for holding all that together than poetry. In the lines of poetry, there’s so much said and so much implied, so much lurking in the silence of a poem and so much present in the text of it.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You” by Yu Xiuhua, translated by Ming Di:

“To sleep with you or to be slept, what’s the difference if there’s any?

Two bodies collide – the force, the flower pushed open by

the force,

the virtual spring in the flowering – nothing more than this

and this we mistake as life restarting. In half of China

things are happening: volcanoes

erupting, rivers running dry,

political prisoners and displaced workers abandoned,

elk deer and red-crowned cranes shot.

I cross the hail of bullets to sleep with you.

I press many nights into one morning to sleep with you.

I run across many of me and many of me run into one to sleep

with you.

Yet I can be misled by butterflies of course

and mistake praise as spring,

a village like Hengdian as home. But all these,

all of these are absolutely indispensable

reasons that I sleep with you.”

[music: “Creatures of Myth” by Gautam Srikishan]

One question that’s really important to ask in any poem is who’s speaking. And the answer is often, I don’t know. Obviously, Yu Xiuhua wrote the poem, but the way that a person uses the word “I” in a poem doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re speaking for themselves. And in this poem, is Yu Xiuhua speaking for herself or a version of herself, a person she’d want to be, a person she was — who knows? — or somebody entirely different? That’s why often, you speak about the “speaker” of a poem.

And then this poem, too, is translated brilliantly, by Ming Di. And every poem is translated — sometimes into a different language, but it’s translated from the page into the person reading it or hearing it, too. Each engagement with a poem is a certain translation, a certain interpretation of it.

In an essay she wrote, Yu Xiuhua wrote about how a person might be constrained by circumstance, and they might create a fantasy for self, and that some might want to disparage a fantasy — a way that you invent a speaker in your life in order to engage in the kind of fantasies that you might think, I wouldn’t be able to do that, but you invent a person, to speak from their point of view. A poem gives you an opportunity to try out new voices — art does. No poem is completely yourself, and even ones that are trying to be self-narrated themselves are only a certain version of yourself. It’s never the fullness of you.

And in this poem, as I wonder who is the speaker — and the question, for me, isn’t is it Yu Xiuhua or not; the question for me is, who are they? What are they like? And they’re philosophical. They’re upfront about sex and desire, a keen observer of landscape and politics and place. And in all of that, I have such admiration for whoever is speaking here, this voice that lifts up off this magnificent page and holds so much of civic observation, together with deep desire.

[music: “Inessential” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There’s deep reflection on what desire is, in this poem: “nothing more than this / and this we mistake as life restarting.” So is she saying that desire is actually life ending, or just starting? What’s she saying? It’s not entirely clear, but she is offering, quite brilliantly, that desire can be many things at once. Desire can be enlivening, or it can be closing. And here, desire is a force, like death and life and drive, and it’s a yearning and a pursuit, and it’s physical, and it destroys and creates, and it can be a distraction, as well.

Toward the end of the poem, there’s this turn: “Yet I can be misled,” and then there’s three things that could mislead whoever’s speaking. And I love them: “by butterflies,” by mistaking “praise as spring” and “a village like Hengdian as home.” You could be misled by beauty, by praise, or by a sense of belonging. What an amazing critique of the human enterprise that’s happening here, not just in the context of desire, but in the context of living; to pay attention to the things that can be misleading, not just the things that are misleading that would be condemnatory, but the things that could be distracting from the true work, which, in this poem, is crossing half of China to sleep with you.

Desire, in this poem, the desire to cross half of China to sleep with you, opens up the speaker’s eyes to paying attention to what it is that’s in the environment — “volcanoes / erupting, rivers running dry” — and then questions to do with politics and workers and the shooting of animals, and bullets. So much is happening here that opens us up to the reality that love and lust and desire must be in conversation as an equal and sometimes disturbing political force within the context of what’s happening in any of our countries. This, I think, is a magnificent tension that this poem holds in a poem that is about unobscured desire, a desire that would make a person cross half a country.

In the context of that, we see what a person’s capable of doing: “I cross the hail of bullets to sleep with you.” Also, there’s the imagination in this poem, too, that the hail of bullets would stop. Desire is a political force in the poem.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

The title of this poem, “Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You,” there’s another time that “half of China” occurs, too, in the poem: “In half of China / things are happening.” And the title and then the repetition of some of that title bring each other into conversation. And this poem is so much about location, but also, more than just location, it’s about locatedness in the natural environment, in the animal environment, and in the political and cultural environment. Where is it that you are experiencing your desire? Where is it going? How is it that this desire will manifest itself in the location where you are? And all of these are being wrapped up into the speaking voice of this overwhelming poem.

Yu Xiuhua was born in Hengdian village in Hubei Province in China, so “Hengdian” that’s referenced toward the end of the poem — you can “be misled by butterflies” or praise or seeing “a village like Hengdian as home” — “Hengdian” is a reference to where she’s from. She was born with cerebral palsy, and that has resulted in mobility and speech needs. And so much of her poetry addresses existential questions of life; questions to do with love and desire and existence and politics and stigma, as well as writing, and also, nature. All of these great existential themes are ones around which her poetry circles.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

One of the deep intelligences of this poem is contained in this line: “I run across many of me and many of me run into one to sleep / with you.” This is an intuition about the reality that no person is just one thing. Every person is many things. And in the context of our relatedness to each other, the many of me relate to the many of you. And this is something that poetry can continually remind us. A speaker in a poem is only a part of you. It’s only a voice of you. It’s only a fantasy or an imagination or a past or a future you, or a you that you’d like to be. And all of these have elements of truth in them, an echo of who it is that’s writing this. And any performed speech, any conversation, is only a part of me. How is it that we can find a way not to try to stuff all of them into one, but to allow the multitudes of the self to be in conversation with the self and with others?

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You” by Yu Xiuhua, translated by Ming Di:

“To sleep with you or to be slept, what’s the difference if there’s any?

Two bodies collide – the force, the flower pushed open by

the force,

the virtual spring in the flowering – nothing more than this

and this we mistake as life restarting. In half of China

things are happening: volcanoes

erupting, rivers running dry,

political prisoners and displaced workers abandoned,

elk deer and red-crowned cranes shot.

I cross the hail of bullets to sleep with you.

I press many nights into one morning to sleep with you.

I run across many of me and many of me run into one to sleep

with you.

Yet I can be misled by butterflies of course

and mistake praise as spring,

a village like Hengdian as home. But all these,

all of these are absolutely indispensable

reasons that I sleep with you.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Hi, friends. Thanks very much for listening to Poetry Unbound this season. This is the last episode of Season 5. Season 6 starts in September, and in October, there’s a Poetry Unbound book going to be released. You can preorder it at your local bookshop or wherever you do that, and we have a Poetry Unbound newsletter that’s starting up this summer, too. You can subscribe to that — there’s a link in the show notes, but you can also just go to onbeing.org/series/poetry-unbound/. We’ve got a questionnaire there and we’ve got information, and I’ll be writing every few weeks about what’s happening, and giving you some insights into the show, and I would love to be in touch with you through that. Again, the link is onbeing.org/poetry-unbound — all in the show notes. And I really look forward to seeing you at events in the autumntime, for book launches, and engaging with you through the newsletter.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You,” by Yu Xiuhua, was published in World Literature Today. Thank you to Ming Di, who gave us permission to use her translation of the poem. Read it at our website, at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Kayla Edwards, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

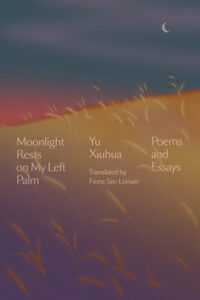

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.