Thupten Jinpa

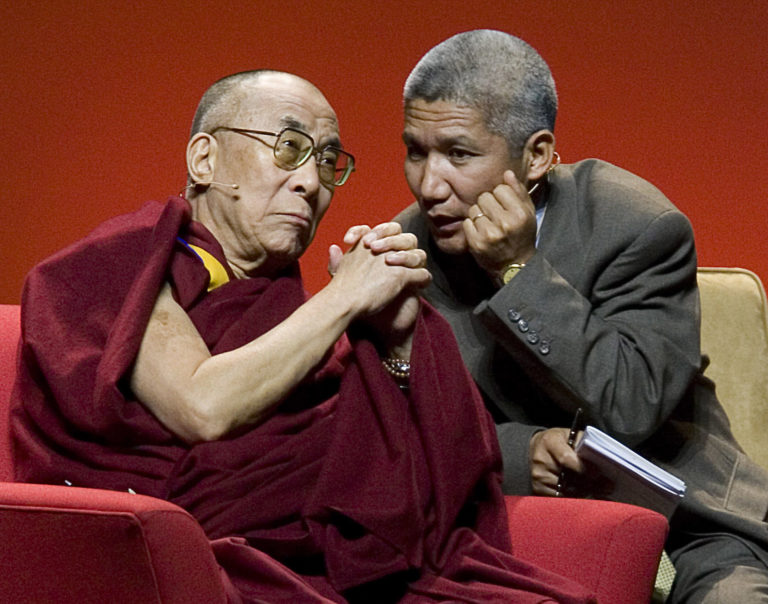

Translating the Dalai Lama

Esoteric teachings on reincarnation and consciousness; simple teachings on compassion and ethics. Geshe Thupten Jinpa is a man who finishes the Dalai Lama’s English sentences. Meet this philosopher and former monk, now a husband and father of two daughters, and hear what happens when the ancient tradition embodied in the Dalai Lama meets science and life.

Image by Stephen Brashear/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Thupten Jinpa is the chief English translator to the Dalai Lama and is the translator and editor of many books, including Ethics for the New Millennium and Toward a True Kinship of Faiths: How the World's Religions can Come Together.

Transcript

February 21, 2013

Krista Tippett, Host: Esoteric teachings on reincarnation and consciousness, simple teachings on compassion and ethics; as principal English translator of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, Geshe Thupten Jinpa finishes the Dalai Lama’s sentences.

[Sound bite of Dalai Lama and Jinpa]

Ms. Tippett: Meet this philosopher and former monk, now a husband and father of two daughters, and hear what happens when the ancient tradition embodied in the Dalai Lama meets science and life.

Thupten Jinpa: One thing that I cherish about the experience of translating for him is the joyful state of mind I can automatically get into. But when I try to cultivate that state of mind in my own quiet sitting meditation, it’s tougher. And this is, of course, a tremendous source of energy and enthusiasm, and also it’s a constant reminder to me that ordinary people can strive to that kind of state of mind. So that I find most transformative.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. This is On Being, from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

Ms. Tippett: Thupten Jinpa’s life story parallels the tumultuous modern history of the Tibetan people. In 1959, the then-23-year-old Dalai Lama escaped Lhasa in secrecy under fear of capture by Chinese troops. Thupten Jinpa’s parents followed one year later, with their four-year-old son and his two siblings in tow.

He entered a monastery as a boy and later studied philosophy and religion at Cambridge. I spoke with him in 2010. These days, Thupten Jinpa lives in Montreal, picking up from there at regular intervals to accompany the Dalai Lama on his extensive public engagements.

Ms. Tippett: I know that you were too young to remember that flight from Tibet that you went on with your parents, and following His Holiness, but I wonder if you grew up with a sense from that experience of what Tibetan Buddhism meant or a sense of a special responsibility to this tradition because of that life experience?

Thupten Jinpa: I don’t think I can say exactly when this sense of responsibility kind of dawned on me, but perhaps one of my earliest memories from my childhood was from this boarding school which was in Shimla in North India. It was a smallish school, and one of my earliest memories, really, the visit of His Holiness to the school. And a whole host of Indian security officials came, police, a couple of hours earlier, and I remember playing marbles with them. That I remember very, very clearly. It was a big deal for the school, you know. And fortunately, a boy and a girl was chosen to offer him traditional Tibetan white scarf, and I happened to be chosen as the boy. I don’t know why, but after His Holiness had the ceremony and we’re walking, you know, from one place to another, you know, across the entrance outside, I remember actually walking holding his hand. I mean, so these are the kind of — very, very early memories I have.

Ms. Tippett: I wonder what — what place His Holiness had in your imagination even from that young age. You know, looking in from the outside, he is such a complex — there are all these aspects to what he represents and who he is, right? On the one hand, he is a national figure of the Tibetan people. On the other hand, he is a reincarnated Lama. On the other hand, he is, as he likes to say, a simple Buddhist monk. Did you think of him as human, divine? I mean, can you put that into words? Because I don’t think there’s an equivalent in the West.

Thupten Jinpa: I think — yeah, I think it’s very difficult to really kind of fully articulate the complexity of, you know, a Tibetan, someone like myself, even after all these years of working for him so closely to really describe the full range of the complexity of, you know, my relationship with him and my perception of him. Even at a very, very early age, I remember very, very clearly that there was on my part a tremendous kind of, you know, a sense of connection with him. I mean, I don’t know why. Maybe, you know, as a kid, I saw him as a father figure and partly, you know, he’s got this wonderful smile, which probably for a young kid, is very comforting.

Growing up later as a monk in a monastic university, then, of course, I had the opportunity to appreciate the more sophisticated aspects of his personality as someone who has gone through the classical Buddhist education, someone who is a deep thinker, as, you know, erudite in the, you know, the most subtle aspects of technical Buddhist philosophy and textual scholarship and all of this.

You know, of course, you know, as Tibetans, we — there is a kind of a mythic dimension to our relation to His Holiness because he’s not just an individual person. You know, he kind of represents a whole institution of the Dalai Lama and, in a sense we, you know, at some subconscious level in the person of the Dalai Lama, we kind of bring together all the inherited wisdoms of the successive Dalai Lamas. So there is that mythic aspect of, you know, at least, you know, my perception of him, which brings a certain richness.

Then later, of course, you know, I had the opportunity and honor to be able to serve him, you know, much more closely as his personal translator. Then, of course, you know, you read about the descriptions of the Bodhisattva in the scriptures, but it’s very rare you see one. But when you see someone like him whose entire being is dedicated to the welfare of other beings and who does it day in and day out, so that was for me very, very, very inspiring actually. I mean, much more so than his sophisticated refined philosophy.

Ms. Tippett: Um, you know, I would like to talk to you— I mean, even with this image you just gave of debating in monasteries. And you didn’t you enter a monastery at the age of 11? Is that right?

Thupten Jinpa: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: That’s a whole layer of Tibetan Buddhism that is unknown in the West and also that can’t— there’s no space for that to find expression in the Dalai Lama’s public appearances. So I would like to draw you out a little bit on that. So, you know, as you say, His Holiness belongs to this and you belong to this vast, in part very esoteric, metaphysical world. I mean, just for starters, for example, I mean, you’ve pointed out that meditation is an English word and that the word meditation that everyone knows now in fact doesn’t carry all of the nuance.

Thupten Jinpa: In some ways, when you see terms like meditation become popularized, it sort of becomes a victim of its own success. The fact that it gets to be popularized means it has become mainstream. But on the other side, you have to pay a price for this. Going mainstream involves some process of kind of reduction where it sort of somehow ends up in its lowest denomination. So in the popular image, people tend to immediately think of meditation as someone sitting quietly, emptying their mind. But if you look at original Sanskrit term, bhavana, and the Tibetan term, gom, from which this term meditation is kind of being used now as a translation.

Bhavana has the connotation of cultivation. It’s like cultivating a field. So there is this connotation of cultivation and the Tibetan term gom has the connotation of familiarity, a process of familiarity. So, uh, and meditation can be, you know, as His Holiness often points out, analytic where it’s not simply sitting down and quieting your mind, but it can actually be a process where you use kind of discernment and move from stages and stages to kind of, in some sense, uncovering layers and layers to get to a point …

Ms. Tippett: So there’s a knowledge that’s being acquired.

Thupten Jinpa: Yes, exactly. But also meditation can be, you know, simply stilling the mind. So of course, when we use in the popular English context, we use the word meditation, all of these nuances get left out. But it’s probably part of the process and, at some point, the nuances will come back because, in the end, you know, I agree with the famous Wittgenstein dictum that, you know, the meaning of a word is its use.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Today we’re exploring subtleties of Tibetan Buddhism with Geshe Thupten Jinpa. He’s a philosopher, former monk, and, since 1985, principal English translator and interpreter of the Dalai Lama. He’s created a project to bring Tibetan Buddhism’s classic texts into the world’s languages. He’s also involved in teaching and research at McGill University and at Stanford. And Thupten Jinpa is chairman of the Dalai Lama’s Mind and Life Institute. This is an ongoing global project that brings scientists and Buddhist practitioners into dialogue, with their very different approaches to human consciousness and knowledge.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me about the knowledge that comes through meditation.

Thupten Jinpa: Well, it’s not simply— the Tibetan tradition is a very complex tradition. And, in some sense, one of the main things that people have to bear in mind is that when people are kind of encountering a tradition such as Tibetan Buddhism, it’s very different historically from, say, any of the monotheistic traditions that you see in the West, particularly in the West. Through history, a process has taken place where there has been a kind of gradual separation between spirituality or religion. And then you have science, which has even further kind of, you know, now confining more and more to a worldview where your understanding of the world is based on what you can directly perceive or what you can infer on the basis of what direct experience can show us. So this kind of separation between science and philosophy and spirituality has not occurred in the context of Tibetan tradition, Tibetan Buddhism.

So Tibetan Buddhism is kind of anti-worldview. Now because of that, you know, you cannot look at Tibetan Buddhism and say this is religion. For the same reason, you cannot say this is philosophy. Or nor can you say this is science, of course, certainly not. But within that tradition, you have all the elements. So a monk’s training involve kind of incorporating all of this, integrating all of this. So philosophy— you know, philosophical enquiry is driven by some kind of understanding of, you know, kind of ethical motivation and aimed at some kind of spiritual goal of enlightenment or whatever you may want to call it, perfection. So that makes the training of a monk very, very sophisticated, because you have to, you know, study all these aspects, the relationship between our perception and the world, and the distinction between true knowledge and a mere belief in assumption. You know, how does a language in thought relate to the actual reality? I mean, these are very, very esoteric questions.

Ms. Tippett: But there is that link that, you’re right, has been severed, decoupled, in the West between knowledge and goodness.

Thupten Jinpa: Sure.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve also said that Tibetan tradition then provides a novel response to this ancient Greek question of why knowledge doesn’t translate into action. What you just said helps explain that, that in fact things are never separated to begin with.

Thupten Jinpa: Sure. It’s partly there, but also partly in the Eastern tradition. It’s not just Tibetan tradition, but also Indian tradition — in the classical Indian tradition in general, there was always the role for meditation and meditation can be seen as a kind of the link between kind of intellectual conscious knowledge and its translation into behavior.

Ms. Tippett: Right.

Thupten Jinpa: So the idea is you can begin with knowledge, but knowledge needs to be totally integrated into the being, into the very personality of the person, so that what comes out in response to a given situation would be something that is ethical — truly ethical and the right thing to do, and that integration can be achieved through a process which we do call cultivation or meditation.

Ms. Tippett: As I remarked before, His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s public teachings are very simple …

Thupten Jinpa: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: … but of necessity, and yet he carries this weight and authority that transcends the words. And so what this helps me understand and realizing this, as I was reading you also in preparation for this, is that the experience of him is not just of the stripped-down teachings, but of the fruit of the teachings, right? Of the cultivation of this very complex tradition.

Thupten Jinpa: Sure, sure. The very compelling thing about him is that, when he talks about, you know, issues like compassion and sense of caring for others and recognition of the oneness of human family, you know, there’s a kind of node of conviction that comes through partly through his body language.

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Thupten Jinpa: That’s why it’s very powerful to …

Ms. Tippett: It’s almost tangible as much as it’s verbal.

Thupten Jinpa: Almost kind of visceral, and the fact that he embodies this is what makes the interaction with him, even in his large public events, very, very powerful. And of course, partly because he wants to really reach everybody, there’s a kind of deliberate simplification of the message. But partly, it’s also because he insists on communicating directly with the audience that he relies on his own amount of English. I mean, his vocabulary is very rich, but then his ability to carry on with complex sentences becomes more challenging. I mean, when you sit there and listen to him, it all seems very, you know, kind of common sense.

But on the other hand, I would argue that it’s the commonsensical nature of his gentle talk that is most profound. Because, in a sense, he’s making us think and not take for granted these things. For example, like one of the kind of memorable things he has said is that the fact that kind of actions of affection, actions of love and caring, do not make headlines is because we take them for granted, which suggests that we expect people …

Ms. Tippett: As normal.

Thupten Jinpa: As normal, to behave in that manner. The fact that killing and violence makes the headlines is because we don’t expect normally people to behave in that manner and, when they do, we are shocked.

Ms. Tippett: We become very confused by …

Thupten Jinpa: Exactly, and he is suggesting that, by not being critically reflective, we sometimes let ourselves driven by headline news and the sad kind of byproduct of that is that people become cynical thinking, “Oh, we’re such horrible species.” Whereas, he says— he’s saying it is the opposite. The fact that they are sensational, that they are news-making, means that somehow in some way we don’t expect fellow human beings to behave in those manners. So these kind of things are very powerful actually. I mean, he’s questioning many of our everyday assumptions and he’s saying, “No, don’t take them for granted.”

Ms. Tippett: You’ve been involved in different ways in the Mind and Life

Dialogues, I believe, which are this extended dialogue which His Holiness has hosted between scientists and spiritual thinkers and you know what they’ve shown about how meditation does affect the brain. I mean, the research that’s come out of that has really changed neuroscience. It’s very full of impact. But how have those conversations and the learnings through them affected you? Have they opened your mind up to knowing or thinking about things that you hadn’t considered before?

Thupten Jinpa: Well, it’s difficult to say. I mean, I have been fortunate to be a part of the Mind and Life Dialogues right from the beginning when it began. The one thing that has changed my mind is probably perhaps the way— as a Buddhist scholar, today I look at many of the mental processes. Of course, as a Buddhist philosopher, we do acknowledge that there are behavioral expressions of your, you know, mental states, but the brain was never really part of that picture.

Ms. Tippett: There was mind was the …

Thupten Jinpa: There is the mind, and then there is your behavior. And as a result of, you know, being part of these dialogues, I’ve come to appreciate how the Western neuroscientific understanding of the brain’s role in mental experience is fairly advanced.

And I have come to now, you know, accept that no discourse on mental phenomenon that doesn’t take into account the brain’s role is going to be complete and comprehensive. So in that sense, although I may not buy into completely the scientific agenda and the underlying assumption that in the end all mental processes are reducible to …

Ms. Tippett: Biology.

Thupten Jinpa: … biology and, you know, brain, biological or biochemistry or whatever it is, basically a physical processes, which I know is a major assumption underlying neuroscience and much of Western life sciences in general. You know, as a Buddhist thinker, I’m not convinced. My own feeling is that the problem of consciousness is going to remain. A philosopher called it the very hard problem and I think, at least for the foreseeable future, it is going to remain a very hard problem. I can’t quite see how, in the end, consciousness can be ultimately reduced to brain processes.

Ms. Tippett: But there’s also still a distinction, or you can ask the question in two ways, right? Whether there is a physical correlate to mental processes or even to what we call consciousness, or whether they arise physically, whether they are purely physical phenomena?

Thupten Jinpa: Sure.

Ms. Tippett: So, you know, this is something I would have asked His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Because of your belief in reincarnation, I mean, that sheds a whole new light on the matter of consciousness, right?

Thupten Jinpa: Sure.

Ms. Tippett: Because, presumably, he is a— well, you say this, but there’s a body, but there’s something complete in fact, as you understand it, that completely transcends the body and moves from one body to another. Is that a discussion in Tibetan circles?

Thupten Jinpa: Yes. Well, not in the Mind and Life circles because His Holiness …

Ms. Tippett: No but, in response to the Mind and Life circles within Tibetan tradition?

Thupten Jinpa: Yes, of course, of course. I mean, the— the— one of the, um, this is probably potentially an area where science and Buddhism may have kind of an important divergence. For Buddhism, it’s very important to at least acknowledge the possibility of consciousness that is— although on the manifest level of experience— may be contingent upon the physical basis, which is the brain. But at some ultimate level, there is a kind of an aspect of that experience of consciousness that is independent.

Ms. Tippett: And when you say consciousness, um, I mean, let’s say again, if in— in terms of the idea of reincarnation, I mean, it’s more than awareness. It’s also aspects of memory, right? I mean, what do you think of? What is involved in human consciousness when you use that word?

Thupten Jinpa: Well, I think at a fundamental level consciousness, I mean, it may be the term consciousness, even in the English usage, there’s a certain ambiguity. Sometimes we refer to consciousness in a sense of being self-conscious. So sometimes people would argue that the animals like rats are not conscious because they have no self-consciousness, but sometimes consciousness …

Ms. Tippett: I’m not sure how we know that but …

Thupten Jinpa: Yeah, exactly, but sometimes people tend to use consciousness in a much more general sense as a way of contrasting consciousness from inanimate material object.

Ms. Tippett: Right. Sentient.

Thupten Jinpa: Yes, sentient. So therefore, the ambiguity of the term, yeah sentient, ambiguity of the term, exists in English as well as in the Tibetan equivalent. But to put it very crudely, by consciousness in the Buddhist philosophy, we mean this primary phenomenon which give rise to all the more evolved conscious sensory and thought processes, so consciousness can be seen as a kind of primary awareness which is a kind of basic property of a sentient being. Now many of the more conscious part of that experience of mental life, say, specific memory of a place or a person or a very kind of you know technical knowledge of certain things, these are very contingent upon experience of what you have.

Ms. Tippett: Which may be rooted in a body, right?

Thupten Jinpa: Yeah, but the underlying that all of this mental experience is, to use William James’ terminology, a stream of consciousness. There is this kind of continuity underlying all of this. And it is this stream that Buddhists would argue gets carried over from life after life.

Ms. Tippett: I see.

Thupten Jinpa: When it passes on, it goes on in a very, very rudimentary basic level, but at the same time, it has all the capacity of expressing itself, you know, into a more evolved form of consciousness. So just because you have experienced something in this life doesn’t mean that you’re going to be able to remember everything in the next life.

Ms. Tippett: But there might be some imprint of that.

Thupten Jinpa: Sure, sure.

Ms. Tippett: It’s true of Thupten Jinpa, as he said about the Dalai Lama, that his physical presence adds another layer to the experience of his ideas. And you can see that for yourself. We videotaped my hour with him along the edges of a conference on happiness with the Dalai Lama at Emory University.

And it was a very different, yet equally interesting experience to be on stage with Thupten Jinpa in his role as interpreter. Find links to these videos on our website, onbeing.org.

There you can also find out how to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. On Facebook, we’re at facebook.com/onbeing. On Twitter, follow our show @beingtweets. Follow me @kristatippett.

Coming up, Thupten Jinpa on bringing monastic training into his transition from monk to husband and father.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we’re shining a light inside the metaphysical and human worlds of Tibetan Buddhism, which is personified in the Dalai Lama of Tibet.

I’m in conversation with his principal English translator, Geshe Thupten Jinpa. He’s a former monk, a philosopher, and a Buddhist scholar in his own right. We’re discussing subtleties of this ancient tradition and what happens when it meets modern science and modern lives. Here he is at work with the Dalai Lama before a live audience of 4,000.

The Dalai Lama: So therefore, we believe, we consider this body is something very precious. [foreign language spoken]

Thupten Jinpa [translating]: For example, in the— there is a Buddhist practices that involve one’s relationship with an attitude towards one’s body, one’s material resources, and also one’s collection of virtues and in the connection to all of these one needs — you know, there are different stages of practice that involve, first of all, kind of letting go and then the second stage …

The Dalai Lama: … under different circumstances …

Thupten Jinpa: … under certain circumstances, we have to …

The Dalai Lama: … the circumstances are such, you see, give your body, your organ, something really benefit, then give. Other circumstances, you must protect.

Thupten Jinpa: Protect. So there’s a kind of a guarding and protecting and nurturing of the body and then …

The Dalai Lama: [foreign language spoken]

Thupten Jinpa: … also a perfection of those resources in body and then increasing and enhancing the capacity. So there’s a complex relationship, you know, with body resources and one’s virtues.

Ms. Tippett: I want to come back to this very human encounter that I have with you this experience that many people have of you when they experience His Holiness the Dalai Lama as his translator. But I have to say, having observed that a few times in a few different places, it feels much more like an intimate conversation that’s happening between the two of you. I’ve even heard people describe it like a marriage, that you’re completing his thought before he finishes his sentence. You know, it’s more than just you interpreting words and it feels like a friendship as well.

Thupten Jinpa: Sure.

Ms. Tippett: You know, just going back to the story you told me about the awe you had for him. I think that also comes through too, that a great reverence comes through. What is that like, then, to develop that relationship with this person?

Thupten Jinpa: Sure. I think when I’m actually on stage assisting him as his interpreter, um, I actually kind of lose the sense of time. You know, I, um, fortunately, because I’ve served in this capacity for now over 25 years, in many instances, it’s not so much that he needs interpretation, but it’s basically, you know, he’s thinking about something and he starts a conversation and my role is to simply follow through the, you know, kind of chain of thought …

Ms. Tippett: Follow that thought to the end, yes.

Thupten Jinpa: And then when he is struggling for a word, simply to suggest so that his struggle for the word doesn’t stop his flow of thought. That has been primarily the kind of role, generally in the public events. But in more technical nature, say, like at a science conference, then there will be a lot more interpretation. I mean, in my case, often I’ll be hearing something that he had already said before, but every time he says it, he says it in a completely different way. It’s very fresh, and the fact that, you know, he truly lives it makes a huge difference. And the sheer joy of his personality, I mean, that person that makes the experience very, very— I mean, for me, I’m almost in a meditative state when I’m translating for him.

Ms. Tippett: But it’s a joyful meditative state in which there’s laughter as well.

Thupten Jinpa: Yeah, yeah, definitely, yeah. I mean, I suppose perhaps I was fortunate enough to establish this close working relationship with him when I was in my monastic years and perhaps there was a sense of collegiality, um, of kind of camaraderie, you know, as kind of fellow monastic members. In fact, when I finally left the order and met him as a layperson, the first thing he said to me was, “Of course, as a senior member of the monastic community, you know, you have to understand that I was very saddened to lose someone like you.” And then he said, “But at the same time, I know you well and I know you have thought about this question very seriously and you haven’t taken this decision lightly.”

So he said, “You know, I trust your judgment.” So that’s the person he is — and he is — I mean, it’s —it’s interesting— what is interesting about His Holiness is that what are opposing characteristics in normal human beings, you tend to see them converging in him. Because normally when you see among religious people, people who are pious, people who are very, very devoted in self-discipline, they tend to be also quite intolerant of others who don’t meet up to their standards. I saw that particularly with His Holiness that this was completely lacking.

You know, when I was a monk, I was never really pious. That was never my cup of tea. I was studious, I was, you know, curious, but piety was never really my cup of tea. So and His Holiness gets up at 3:30 in the morning. You know, I even have difficulty getting up at 5:30 or 6. So for a monk that’s fairly late, but I never felt being judged by him, you know, even when I was a monk that somehow I wasn’t living up to the standards that the monk was expected to be, you know. So this is an amazing thing about him. And another thing is that normally when you see people who have tremendous self-confidence, then humility is not really a part of their characteristic. You know, with powerful self-confidence comes a certain sense of pride and arrogance. Again, in His Holiness, this arrogance is completely missing. He’s at a personal level very humble, but at the same time, tremendous self-confidence.

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Thupten Jinpa: So this is an interesting juxtaposition of what generally can be contrasting kind of, you know, characteristics. And one of the things that amazes me is that he has this gift to be fully present, you know, when he’s talking to someone. It doesn’t really matter whether the person in the room that he’s talking to is the president of a country or whether it is just an ordinary person. The way in which he treats, just none of these mundane considerations, you know, have any role and that is an amazing, you know, kind of quality because it’s very, very difficult. And another thing is that, in him— you know that Tibetans particularly adore him, worship him, you know, one could argue, but none of this goes to his head. He remains humble at a personal level. So these are what makes it amazing for me to have this opportunity to work for him. You know, after all these years, you know, my affection for him, my admiration and my respect, even my sense of awe remains undiminished.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah.

[Sound bite of Tibetan chant]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. My guest, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, has spent a quarter century as the Dalai Lama’s English interpreter. He’s a philosopher, a former monk, and Buddhist scholar. And he’s become a close collaborator on the Dalai Lama’s dialogues with scientists and on his English-language writing projects.

Ms. Tippett: So you are married now, right, when you left the monastic order. So how long have you been married?

Thupten Jinpa: Fourteen years now.

Ms. Tippett: And you have two children? Is that right?

Thupten Jinpa: Two children.

Ms. Tippett: So I heard this— anyway, when we were researching you, a question and answer with His Holiness, and someone asked him about anxiety and stress. He said, “Well, even monks and nuns are caught in anxieties and my advice is to live simply.” And he said: “My translator, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, can answer that question better. He was a monk, now he’s a father. As a monk, he slept peacefully. Now as a father, his child wakes him up when he’s asleep.”

I do wonder how— well, one thing that occurs to me is that maybe as a parent you also have a different insight into the longings and the stresses that people bring when they hear his teachings and that this life— I mean, even I know I read about that he gets up at 3:30 and meditates for hours before every day. But I have children too; that feels like a dream. How has that changed you, formed you, made you a different Tibetan Buddhist and a different colleague to His Holiness?

Thupten Jinpa: I think you are right. I mean I — well, one thing that surprised me a bit was actually how challenging relationships can be. You know, although as a monk, you know, we live in a community, there are relationships. But relationships are more that of teacher to student and to fellow monks as colleagues. Then we have within the monastic community, the setup is we have smaller families within which we live together. But none of the challenges that we have, you know, in any given social context where there are more than two or three people, there’s always going to be some challenges in the context of relationships, because that’s, you know, what we are, human beings.

But what surprised me a little bit was how actually tougher it was to have an intimate marriage partner and to live in a truly, you know, sharing life. That was tougher. But on the other hand, I truly feel grateful that I went through the monastic life, because the discipline it taught me and also it may sound strange, but certain degree of emotional independence I found tremendously helpful.

Ms. Tippett: As a married man.

Thupten Jinpa: As a married man, so that you don’t dump all of your baggage on your spouse, and somehow when your spouse is annoyed or angry, somehow to be able to relate to that in a more compassionate manner so that you don’t take it personally. So that — and also it has partly to do with the kind of compassion training that we go through in the monasteries, you know, putting yourself in other peoples’ shoes and trying to enhance one’s empathy.

So these kind of things, the best way I could describe this is some degree of emotional independence so that your relationship is not completely this kind of needy and this clingy and grasping. So that I was very happy to see that my monastic years really helped, and also this basic discipline as a monk that I was able to bring into my life. That was but at the same time, what was very, very valuable as a layperson is the sheer joy and also the headache that comes with being a parent. You know, and— and His Holiness, of course, when he talks about cultivation of compassion, he says that, because of the biological factor, you know, women in some sense have greater propensity and greater sensitivity to other’s pain. Therefore, there needs to be more women in the public role, particularly in the leadership role.

You know, something similar to this is what I experienced as a father, that there is a certain visceral feeling of love and compassion to your children that, as monks, probably will take ages to cultivate. Um, that, you know, as parents, you know, these come very naturally and you can see, especially when the children are young. And as they get— now my two girls are kind of teenage and preteen, so it gets more complicated. But especially when they are very young, you know, their needs are very real and their needs are very urgent and their needs are for now, you know. And, and so one thing I noticed is that, in the parental love, the quality of unconditionality is very powerful. Whereas as a monk, you don’t have that opportunity except towards your teacher. But then there is a kind of hierarchy. You know, it’s to someone who is an object of reverence.

Ms. Tippett: Right. So this really gives you an experience, of an expression of these things you were learning in the monastery that …

Thupten Jinpa: Oh definitely, especially the unconditionality of, you know, this is truly selfless nature of the parental love to your child. And this is powerful.

Ms. Tippett: What comes to mind as the most unexpected and formative experiences you’ve had as a translator? This is my last question.

Thupten Jinpa: Well, that’s— one thing that I do kind of, you know, cherish deeply about the experience of translating for him is the quality of the joyful state of mind I can automatically get into when I’m there. But when I try to cultivate that kind of state of mind in my own quiet sitting meditation, it’s tougher. So probably it has a lot to do with the ambience, the fact of being next to him, the sheer kind of presence of his kind of being and his compassionate energy, whatever it may be. But there is a kind of state of mind that I get into, you know, quite naturally. And this is, of course, a tremendous source of energy and enthusiasm, and also it’s a constant reminder to me that ordinary people can strive to that kind of state of mind.

So that probably for me I find most transformative part of my work for him, but also the other part that I truly value is the opportunity to assist him very, very closely on some of the books that have had huge impact on the wider world, for example, Ethics for the New Millennium …

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Thupten Jinpa: … which is an attempt to articulate and envision what a secular approach to ethics would look like; that is, an approach that is respectful to all the perspectives of the multiplicity of religions, but at the same time, you know, it does not require— subscribe to any particular religious belief or faith. And that was done out of a sheer compassion by His Holiness for the world in a concern that somehow we need to promote the culture of compassion. So I had a kind of, you know, great opportunity to work with him closely on that.

[Sound bite of music]

Thupten Jinpa: Another book that I assisted him was the book that told his story of many years of engagement with science, scientists: Universe in the Single Atom. You know, for me, the most compelling part of that book, in addition to personal stories is the over-arching theme, which is the need for taking compassion to be central in human motivation and not forgetting that science is one among many human activities that are ultimately aimed at betterment of humanity.

Somehow that ethical consideration that underlied, you know, the whole scientific revolution in the early days must not be forgotten and how the scientist, particularly in the field of biogenetics, they’re now creating new realities which human beings never confronted in the past, which has huge implications for the survival of the species in the world. As a whole, he’s appealed to the scientists to not take these lightly, but to take the ethical responsibility of what they’re doing seriously.

And then just recently, I’ve finished, um, he finished a book that I assisted him on, which tells his story of more than 50 years of engagement in other religious traditions, and it’s toward, you know, the true kinship of faiths, how the world’s religions kind of come together. And again here, one of the powerful chapters in that book is the argument that, despite all the diversity and the doctrinal beliefs and the metaphysical, you know, idea theories underpinning those doctrinal beliefs, when it comes to the prescription of how to lead a good life, an ethical life, there is a tremendous convergence across all the major traditions and these traditions were divided across time, across geography, across culture, across language, and all of these prescriptions in the end comes down to compassion.

Compassion is the foundation of, you know, moral teachings for all the world religions. And I think this is a powerful message that people in the religious world, as well as the secularist, need to heed because, if this is true and if we can convince ourselves that this is the foundation of all of our value system and compassionate nature is a key aspect of who we are, then we will tell ourselves a different story. And if we tell ourselves a different story of who we are, then the chances are that we’re going to try to act in accordance with that story. I think these— I feel tremendously privileged, because, as an ordinary person, I will never have a chance to have that kind of outreach to the world, but by serving him for these books, I’ve really have an opportunity to at least contribute to this process. So these are what I find, you know, deeply transformative, yeah.

Ms. Tippett: Well, Thupten Jinpa, thank you so much.

Thupten Jinpa: Thank you. It was a joy.

Ms. Tippett: Geshe Thupten Jinpa is the Dalai Lama’s principal English translator and president of the Institute of Tibetan Classics in Montreal, Canada. He is also a participating scholar and executive committee member of Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education.

You can listen again, download this program, or watch my entire conversation with Thupten Jinpa at our website, onbeing.org. There you’ll also find video of him acting as interpreter in a public discussion on happiness with the Dalai Lama and three world religious leaders.

While you’re at onbeing.org, sign up for our weekly email newsletter. It’s a capsule of what I’m reading, your exchanges with us on Twitter and Facebook, and words and images that grab our imagination in our digital spaces delivered to your inbox. Sign up at onbeing.org.

You can also keep in touch with us at Facebook.com/onbeing. On Twitter, use the hashtag #onbeing and converse with other listeners. I’m there @Kristatippett. Follow our show @beingtweets.

On Being, on-air and online, is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, Susan Leem, and Stefni Bell. Special thanks this week to the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University. Our senior producer is Dave McGuire. Trent Gilliss is our senior editor. And I’m Krista Tippett.