Patrisse Cullors + Robert Ross

The Spiritual Work of Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter co-founder and artist Patrisse Cullors presents a luminous vision of the spiritual core of Black Lives Matter and a resilient world in the making. She joins Dr. Robert Ross, a physician and philanthropist on the cutting edge of learning how trauma can be healed in bodies and communities. A cross-generational reflection on evolving social change.

Image by Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

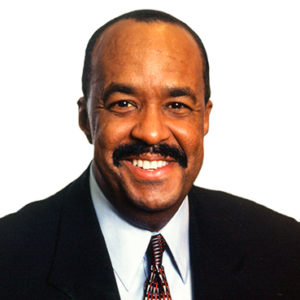

Robert K. Ross is president and chief executive officer for The California Endowment. Trained as a pediatrician, Dr. Ross has been a leader in work surrounding trauma, resilience, and community as a clinician, public health executive, and health philanthropist. He previously served as director of the Health and Human Services Agency for the County of San Diego and as the Commissioner of Public Health for the City of Philadelphia.

Patrisse Cullors is a co-founder of Black Lives Matter and the founder of Dignity and Power Now. She is currently touring with her multimedia performance art piece POWER: From the Mouths of the Occupied. Her artwork can be found on her website.

Transcript

May 25, 2017

Krista Tippett, host: We’ve heard a lot about Black Lives Matter, but you may never have heard one of its co-founders reflect outside a moment of crisis, presenting a luminous vision of the resilient world we’re making now. I met Patrisse Cullors, who is also an artist, in a cross-generational conversation with Dr. Robert Ross. He’s a physician and a leader who is helping redefine public health in terms of human wholeness. They give voice to the generative potential in this moment we inhabit — its courage and creativity, its seeds in trauma and resilience, and its possibility for all of our growth as individuals and community.

Ms. Patrisse Cullors: You see the light that comes inside of people to other communities that are like, “I’m going to stand on the side of black lives.” You see people literally transforming. And that’s a different type of work. And for me, that is a spiritual work. It’s a healing work. And human to human, if you take a moment to be with somebody, to understand the pains they’re going through, you get to transform yourself.

Dr. Robert Ross: I think what Black Lives Matter is a living case study about is about narrative change and framing. Because then it leads to, “OK, if black lives matter, then what does it mean for schools?” “If black lives matter, then what does it mean for police reform?” “If black lives matter, what does it mean for economic development and jobs?” And so it leads to a whole host of, “OK, so if that’s true, what does that mean?” I think for those of us in my generation, Patrisse, who are in charge of stuff, it challenges us to rethink our frames and pick different kinds of fights.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Ms. Tippett: My conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Robert Ross took place in 2016 with an invited audience of social change and nonprofit leaders. We’re at the Los Angeles headquarters of the California Endowment, which Dr. Ross leads.

Ms. Tippett: We most often grapple publicly, I think, when it comes to Black Lives Matter and our whole encounter with racial and social inequity, in terms of news events and violent injustice and political and legal actions. And I’m sure we will touch on those things in this conversation. But what we’re also trying to do at the same time this morning is carve out a space to explore human and spiritual underpinnings and promise in these things.

And so I want to start with a little bit — just hearing a little bit about the spiritual ground and formation of each of your early lives and focus that on what you would now — perhaps not then, but now — call experiences of trauma and resilience that were seeds of the passion for addressing these things that you’re now bringing to all of us. And Patrisse, I want to start with you. You grew up here in Los Angeles in the 1990s.

Ms. Cullors: Born and raised.

Ms. Tippett: Born and raised. Yeah. So where does your mind go if you think about the spiritual underpinnings of your life as they had to do with what you would now call trauma and resilience?

Ms. Cullors: I love this question. We don’t get asked these things a lot in our movement. But, one, I just want to say thank you. Thank you for having me on, and thank you, California Endowment, for inviting me. And for me, I feel like I’m not just bringing myself, but I’m bringing the movement into this conversation. I’m bringing my ancestors into this conversation. And my great-grandmother, Jenny Endsley, who would’ve been 103 just a couple days ago, is a deep reminder for me around why I do this work.

She raised me and my three other siblings while my mom had to work three jobs to barely get food on our table. And she was both Choctaw, Blackfoot, and African American, grew up in Oklahoma. Her father was a medicine man. And she told us lots of stories about the KKK, lots of stories of her father defending their family against the KKK, and her eventual move to Los Angeles.

And she was probably one of the most glamorous women I ever met. She had hundreds of wigs in her closet and lots of sequins, and she was this amazing singer and had such a powerful impact on me and my siblings and my family’s life because she stood up for black life so fiercely throughout her lifetime. And that looked like being a part of the NAACP; it looked like picking up her black grandchildren all the time from after-school programs; it looked like helping my mom navigate a system that was consistently trying to separate her from her children.

And so those are sort of my early years of understanding my own formation here in Los Angeles. And then my grandmother was the first person to put me on stage. I wrote a speech, “If I Were President,” when I was in second grade, during the first Bush administration. And she would always ask me, “What did you do in school today, grandbaby?” And I read the speech to her, and she was like, “Oh, well, I’m going to have you read that speech at the women’s club.”

And I remember getting on stage at 9, reading this speech, “If I Were President,” her giving me this trophy, and it was just this moment where I was like, “Oh, someone believes in me. Someone believes in what I have to offer.” And I think what we forget when we are raising young black children is that the belief in them is absolutely necessary in building their own spiritual foundation and their own fortitude. And I believe if I didn’t have my great grandmother, who deeply believed in me and my siblings, I would not actually be who I am today.

Ms. Tippett: That story is so wonderful, and I love that the question elicited a whole different answer because that story you just told about your grandmother and her glamour and that belief and that beauty and courage, strength was against a backdrop, which is the story I’ve heard more often, of growing up in Los Angeles in the 1990s in a neighborhood full of crack addicts and crackdown, which, as you said, had essentially criminalized poverty and the effects of poverty. But it’s that both/and is what brought us you now.

Ms. Cullors: Yes. And I think it’s important in this current historical moment that we’re naming the tragedy and the resilience. So the tragedy is black people are being killed often and continue to be killed often. The tragedy is that black people are living in poverty. Black folks have the highest rate of homelessness. Those are the tragedies, but there is this — also this other side, which is this amazing movement that is challenging age-old racism and discrimination. And I always tell audiences what a great time to be alive to show up for this current historical moment.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. So Bob, you grew up in the South Bronx, and I don’t know a lot about your upbringing. How would you start to talk about the formative seeds for your passion about trauma and resilience?

Dr. Ross: Sure, yeah. Patrisse, by the way, do you still have that speech that you wrote in the second grade?

Ms. Cullors: I don’t know if I still have it. [laughs]

Dr. Ross: I would love to see it. Yeah, so, my upbringing, a bicultural upbringing, my father’s African-American. My mother’s Puerto Rican. We grew up in the South Bronx at a time when it was — still is a challenged community. My mother was — at the time, I didn’t realize she was a community organizer, but she was. I mean, in retrospect, I now know she was a neighborhood organizer, and she would rally neighbors and residents to, for example, try and take back this vacant lot that the kids used to play in and had glass and rocks and litter and try and take it back as a park for the kids — for us kids and try and shoo away the drug dealers from the park. And so my brothers and I thought she was just this nosy busybody, but…

Ms. Tippett: Which is what made old-fashioned neighborhoods healthy. [laughs]

Dr. Ross: Exactly. Little did I know that she was teaching me a lot about what my work would look like. I would say, for me, the spiritual pivot, if you will, that’s related to the work that I do — my staff has heard me say this — you mentioned crack cocaine. When I was a practicing pediatrician in the mid ‘80s, late ‘80s, early 1990s in Camden, New Jersey and in North Philadelphia is when crack cocaine came to the United States, when crack cocaine came to neighborhoods like — communities like Detroit and Los Angeles and New York.

It was an awakening for me in a couple of fronts. One, before 1984, poor people couldn’t buy cocaine. Crack cocaine gets — some evil genius comes up with crack. All of a sudden, the euphoric, short-acting passport to nirvana known as crack cocaine hit neighborhoods and communities. And for five bucks, you could buy your way into euphoria and into hope. But it’s a very short-acting, 20-minute drug, and then you have to get at it over and over and over again.

So that got introduced into inner city communities, and it had a substantive impact on my experience in the community as a pediatrician and a healer because now we’re seeing youth violence go through the roof, gun violence go through the roof, massive increases in property crimes and personal crimes, mothers, pregnant mothers and young mothers, forgetting that they were actually mothers and parents of children as a result of being addicted to crack, attending a lot of deliveries of crack babies. And I was being introduced to what we call later the “social determinants of health,” the roles that poverty and hopelessness and housing and lack of jobs all play in wellness, in health and healing.

Ms. Tippett: I don’t know when you were born, but how did the Civil Rights Movement intersect with your coming of age and your consciousness about these things?

Dr. Ross: Yeah. I feel like I’m in the lost generation, which is why — so it was my parents’ generation who weathered the Depression, defeated Hitler, brought the Civil Rights Movement. So, on my dad’s watch and my parents’ watch, they did all that, OK?

Ms. Tippett: Which was as much in the ‘50s as the ‘60s, although we tend to think of it as the ‘60s, right? Yeah.

Dr. Ross: Yeah. So I came in at the tail end of the Civil Rights Movement, enough to remember Martin Luther King on television, but not marching. I was too young. And so I feel our generation has pretty much dropped the ball.

Ms. Tippett: I’m curious for both of you about — so we are remembering our own history. I also wonder how you think about ways in which that movement and all it stood for, if there are things we are only now able to appropriate. I mean, I think about W.E.B. Du Bois saying, “The problem of the 20th century is the color line.” What we didn’t know in the 20th century, what we know now through science is that there’s also a color line in our heads.

So that even as we pass laws and most of us, the vast majority of us, decided that racism was wrong and bad and didn’t apply to us, we still continued to behave in ways that didn’t sync with that. And I wonder how — to both of you again, are there ways you think we are able now to rise to this occasion, that we have some — that what tools do we have, what knowledge do we have that they didn’t to live into that vision?

Dr. Ross: One blink reaction to that question, Krista, is what this generation has that we didn’t have: social media.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, right. A movement that started with a hashtag or a new narrative that started with a hashtag.

Dr. Ross: And you mentioned a term, “narrative change.” So I think what Black Lives Matter is a living case study about is about narrative change and framing. Because then it leads to, “OK, if black lives matter, then what does it mean for schools?” “If black lives matter, then what does it mean for police reform?” “If black lives matter, what does it mean for economic development and jobs?” And so it leads to a whole host of, “OK, so if that’s true, what does that mean?” And I think for those of us in my generation, Patrisse, who are in charge of stuff, it challenges us to rethink our frames and pick different kinds of fights.

Ms. Cullors: I would argue the same thing: social media. I don’t believe social media is the end all be all, but what it has allowed for is a new generation to speak from their own perspective. It’s allowed for a new conversation, new reach. I think a new generation of anti-racism white allies have been really important in this conversation. And I remember specifically after the acquittal of George Zimmerman how many anti-racist white folks wrote stories about their own whiteness and their relationship to it. And it was this powerful conversation with sort of like the public in this vulnerable way around how people are continually behaving and supporting anti-black racism by their own behavior.

And when Mike Brown was murdered, we saw another round where whole communities, non-black POC communities in particular, coming out and saying, “You know what? My community is deeply anti-black, and I want to challenge that.” And so we get to see a new generation speak for ourselves through social media, through online platforms. We’re living in the era of people writing blogs all the time. And social media accounts, although sometimes really self-absorbed, can be really self-reflective, and I think it’s powerful.

Ms. Tippett: It also presents a whole different model for how social change happens. I think most of us, at the end of the 20th century, would’ve thought social change is about large numbers of people on the streets, charismatic leaders, and that is how it worked. But this is much less leader-centric. It’s a network of change. It’s also amorphous, right?

I mean, and I know you hear this, and I also want to ask you — when there’s criticism of Black Lives Matters, that rage is out front. And when people compare the Civil Rights Movement of 50 years ago with Black Lives Matter, they say “Where is the love?” And I want to talk about love in a minute, because I don’t want to just throw that word out there because it’s a big, robust word. But there are dialogues, like, between Ta-Nehisi Coates and Cornel West about — it’s not just Black Lives Matter, but is — if rage is at the center, what is being created in terms of building a different world? So how do you respond to that discomfort?

Ms. Cullors: Well, I disagree. It’s both rage and love at the center of our work, I think. From the beginning, Alicia Garza’s “Love Note” to black people that ended with, “Our lives matter, black lives matter,” it was from a place of rage, but also from a place of deep love for black people. And I think that — when we show up on the freeway, when we chain ourselves to each other, that’s an act of love. That act of resistance is an act of love, that we will put our bodies on the line for our community and really for this country. In changing black lives, we change all lives. And I think that’s the conversation that needs to be penetrated into folks, right? This conversation about black lives mattering is a conversation about all lives mattering, and I think that our work shows as such.

When we have actions of people — have they ever been a part of a Black Lives Matter action — it’s deeply spiritual. It’s often led by opening prayer. Folks are usually sage-ing. We use a lot of indigenous practices. People build altars to people who have passed. And so it’s this moment to both stand face-to-face with law enforcement, but it’s also this moment to be deeply reflective on the people who’ve been killed by the state and give them our honor. It’s an honor to protest for them. So many of our people, names have been lost, and so we’ve said, “We will not forget you. This protest will keep you remembered.” And Sandra Bland was a perfect example. When she was arguably killed inside a jail cell, we said, we will not forget your name, because so often the names are forgotten.

[music: “1993” by Emancipator]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors and physician and California Endowment President Robert Ross.

[music: “1993” by Emancipator]

Ms. Tippett: I think this is a tricky conversation to have because — one thing you’ve said is “Black Lives Matter” — and this was probably a moment — “Black Lives Matter at this moment is about exposing.” And that is what has been so galvanizing. So — I have a 17-year-old son who’s a white boy, and there was a killing in Minneapolis. He talked to me about how he heard news from Baltimore and St. Louis and Los Angeles and New York and thought that doesn’t happen here.

And then there was a vigil at his school and all these kids — he goes to a great big urban high school. All these kids he’s been at school with for years stood up and told stories about things that had happened to them. It was completely shocking to him, things like what happened to you in your childhood — their fathers being dragged out of their houses and taken to prison. So this “exposing” — this is pretty amazing. I don’t think you can put this back in the box. And it was in a box, and that’s what we realized.

Ms. Cullors: Yes, a tight one. Yeah, I was — I mean, it was in the box for a part — there’s two Americas. For those of us who’ve lived in it, it was not in a box. We were experiencing it on a daily basis. It’s been trying to expose it to the America that has kept it in the box and that has been able to have the privilege to not witness, to not go through. I think now that that’s been exposed to the other America, you can’t put that back in. There’s no turning back.

Dr. Ross: To your question, Krista — and I’m not a scholar in the history of social movements and activism. It’s not what I do. I try to learn. We try to learn. But in the moment and at the time, the activists are employing a form of strategic outrage, right?

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Dr. Ross: And at the time and at the moment, they’re always criticized, marginalized, targeted for being outrageous, right? I mean, Martin Luther King is now on a stamp, and it’s a holiday, and there are parades. And as you mentioned earlier, Patrisse, he was detested…

Ms. Cullors: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Dr. Ross: …in many circles during his time, as was Gandhi, as was Mandela, put in jail for 27 years, and it was just fine, thank you. And so, if you’re not being accused of being outrageous, then you’re probably not successfully deploying activism, is one point. The second point, which I hope we get to — I just want to tease it — the science on the trauma side and what it does to us is a lot better developed than the resiliency side, but there is something about civic activism and engagement that appears to be powerfully immunizing against poor health. We know there’s something quite holistically health-supporting.

Ms. Tippett: Life-giving.

Dr. Ross: And life-giving when those young people are engaged.

Ms. Tippett: Mm-hmm. And you’ve both spoken about how young people, in particular, experience injustice with an immediacy and a rawness, take it in in a way that — to varying degrees we learn or try to learn to shield ourselves as we get older. So let’s talk about love. Love was a pivotal, essential word in that original Civil Rights Movement, I think, even for King and everyone around him, but also Malcolm X in the end. But it was a complex, robust vision of love, right? And that language of the “beloved community,” which is what everything was aiming towards, was also full of biblical imagery.

I heard something that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about. At the American Academy of Religion meeting this year, which is, like, 12,000 theologians, Ruby Sales, one of these women whose name we don’t remember, talked about how — she said, “None of us considered ourselves to be religious in the way our parents or grandparents were and there was a lot of religion, but we were rejecting so much of what we’d grown up with. We didn’t think that defined us. And we only realized later that even though that was true, we were steeped in that tradition, in the hope, in the sense of love, in the songs, in the community. We had our armor on.” And she said, “And then we became involved in policy, and we sent our children out into the empire without their armor on.” And I’d love to know how you hear that and think about it.

Ms. Cullors: I love that. I love that she said that. I think we think about it differently. I mean, to be honest with you, so many of us in the Black Lives Matter movement have either been pushed out of the church because many of us are queer and out, many of us — the church has become very patriarchal for us as women and so that’s not necessarily where we have found our solace. And I think we have had to contend with that during this movement. How do we relate to the black church and how do we understand ourselves in relationship to the black church inside of this movement?

But that hasn’t stopped us from being deeply spiritual in this work. And I think, for us, that looks like healing justice work, the role of healing justice, which is a term that was created probably about seven or eight years ago and was really looking at how, as organizers, but also as people that are marginalized that are impacted by racism and patriarchy, that are impacted by white supremacy, how do we show up in this work as our whole selves? How do we be in it as our best selves? And how do we look at the work of healing?

I’m really appreciative that Dr. Ross calls himself a healer because I believe that this work of Black Lives Matter is actually healing work. It’s not just about policy. It’s why, I think, some people get so confused by us. They’re like, “Where’s the policy?” I’m like, “You can’t policy your racism away.” We no longer have Jim Crow laws, but we still have Jim Crow hate.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. But see, that, I think, is a new insight. Right? I just don’t think they knew that 50 years ago.

Ms. Cullors: Yeah, I think that’s true. I think when there are laws on the books that are so hateful, of course our first instinct is to get rid of those laws, transform those laws, reform those laws. But there’s something much deeper inside of us that causes our behavior to be biased or discriminatory. And to me, racism is a sickness. If we’re approaching racism and sexism and homophobia as sicknesses, you’re not just gonna think, “Well, if someone writes standards over and over again, “I will no longer be racist, I will no longer be racist,” that it’s going to change them. No, it takes something else. It takes a sort of exorcism. I deeply believe that. And you see it in people’s transformation in this work.

In the last year and a half, from the black community in and of itself, as we say “black lives matter,” and sort of you see the light that comes inside of people to other communities that are like, “I’m going to stand on the side of black lives,” you see people literally transforming. And that’s a different type of work. And for me, that is a spiritual work. It’s a healing work, and we don’t have it codified. There’s no science to it. Really, it’s — we are social creatures. Human to human, if you take a moment to be with somebody, to understand the pains they’re going through, you get to transform yourself.

And I think the last thing I’ll say is Black Lives Matter is a rehumanizing project. We’ve lived in a place that has literally allowed for us to believe and center only black death. We’ve forgotten how to imagine black life. Literally, whole human beings have been rendered to die prematurely, rendered to be sick, and we’ve allowed for that. Our imagination has only allowed for us to understand black people as a dying people. We have to change that. That’s our collective imagination. Someone imagined handcuffs; someone imagined guns; someone imagined a jail cell. Well, how do we imagine something different that actually centers black people, that sees them in the future? Let’s imagine something different.

[music: “Quiet” by This Will Destroy You]

Ms. Tippett: You can listen again and share this conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Robert Ross through our website, onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Quiet” by This Will Destroy You]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, in a cross-generational conversation about the courageous, resilient world we’re making now, with artist and Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors and physician and public health leader Robert Ross. We’re at the Los Angeles headquarters of the California Endowment, which Dr. Ross leads.

Ms. Tippett: Bob, I want to pull you into this in a minute. I do want to give a shout out. Diane Winston is here from USC, and actually, the only place I saw writing about the spiritual aspect of Black Lives Matter was in Religion Dispatches. Did you see that piece?

Ms. Cullors: Yes, of course I did.

Ms. Tippett: It was terrific and they …

Ms. Cullors: It was wonderful.

Ms. Tippett: It was just telling — it said, “When you think of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, you may think of Ferguson, you may think of Baltimore, you may think of ‘I Can’t Breathe.’” It goes on and talks about this aspect of the movement, and it says, “Black Lives Matter’s chapters and affiliated groups are expressing a type of spiritual practice that makes use of the language of health and wellness to impart meaning, heal grief and trauma, combat burnout,” — which the original Civil Rights leaders will tell you they weren’t good at — “and encourage organizational efficiency.”

And, Bob, it seems to me that this also, again, it gets at what the work you and California Endowment are doing with trauma and resilience. Working with that is precisely in the same field. You’ve written about the old saying that time heals all wounds is simply not true. “Not these wounds.”

Dr. Ross: Yeah. And what we struggle with, as a private health foundation, we want to be disciplined and anchored in what the science says about improving public health and well-being, right? And so now we’re talking about love and justice and movements, and it makes our heads spin. How do we connect?

Ms. Tippett: Well, and it’s the narrative of those things doesn’t allow for such words, or it’s uncomfortable with such words.

Dr. Ross: It is — we’re getting increasingly comfortable with it. We’re beginning to get over ourselves, I think, as many of our grantees notice. So a couple of quick sort of concrete examples of how the love thing plays out in the work that we do. Many of the folks that are here in the audience worked with young people on the school discipline reform, zero tolerance, school suspension issue, which came to us from the mouths of young people themselves, was not on our radar screen as a health foundation.

They said, “We want you to help us get rid of zero tolerance.” We said, “What are you talking about?” As a parent, I’m thinking zero tolerance is a good thing for schools, isn’t it? They said, “No, it’s not. It’s the portal to the incarceration super highway.” But what they were also saying to us that the science and the research bears out in terms of their experience is, think about the message you are sending to a young person who is acting out in school, for whatever reason or however you defined “acting out,” and you suspend them or expel them out of school. If that is not the opposite of love, I don’t know what is.

Ms. Cullors: Exactly, right.

Dr. Ross: Right? That is an act of unlove, right?

Ms. Tippett: Right.

Dr. Ross: And then the data, if you’re suspended one time, even one time, you have a two to three times likelihood of being involved with the incarceration system, of dropping out of school.

Ms. Tippett: I think you also say that in the juvenile justice system, there is, in fact, no question — no interrogation of is there trauma in this life?

Dr. Ross: Exactly. I mean, so there’s a movement now, and I’m sure Black Lives Matter is — I’m sure you’re absolutely at least familiar with this if not part of the platform, Patrisse — why do we have juvenile incarceration at all, period? For anybody in this country, right? And so, again, we are criminalizing sick, traumatized, oppressed children early.

This is powerfully spiritual, important work upon which the future of this nation rests, and I think it calls upon us to bring the best of the total experience of our best selves to the table. It’s not — we can’t mail it in on addressing inequality in this nation. Each of us is going to have to bring the best of ourselves to the equation. Not just the best of ourselves, but the best of ourselves in unity and in coalition.

Ms. Tippett: OK. So if you have questions, why don’t you write them down, and then we’ll open it up.

Audience Member 1: Hello, and thank you so much for the jewels of wisdom that you’ve brought. My question is, someone said to me recently and it really resonated, that the system is without a soul. And in the midst of your work, especially around pushing policy, how do you suggest that we bring some spirit back into the system?

Ms. Cullors: Yeah, that’s the truth. It’s very personal when you’re working on these fights that your life has been impacted by. And I think — I’m not clear if the system can gain a soul. I’m not sure that that’s what their purpose is. But what I think we must do is not lose our own because it is very easy when you’re fighting big systems who crush whole communities to feel like, “Well, what’s the point?”

And I think the point is — although a victory is amazing, let me tell you. I’ve had some victories, and that feels good. The point isn’t necessarily the victory. The point is building the power of our communities, and that looks like the organizing. It looks like what it takes to have those conversations. It’s the door-knocking. It’s the community meetings. It’s the idea that we had the audacity to imagine something different for ourselves.

I think the Civil Rights Movement talked about it a lot, right? We might not see these things in our lifetime, but if it’s about something bigger than us, then we’re going to stay in it for the long haul because the hope is 100, 200 years from now, this place will still be in existence, and that we will have left it better off.

Audience Member 2: I’d like to know your thoughts about reparations?

Ms. Cullors: Do you want to talk about…

Dr. Ross: No. [laughs]

Ms. Cullors: OK.

Dr. Ross: I want to hear what you have to say.

Ms. Cullors: Yeah, I’m a strong believer in reparations. I’ll specifically talk about the community of Flint right now. If any community in this moment in history needs and deserves reparations, it’s that community. We have no idea what the long-term impacts of a community who have been ingesting lead for two plus years is going to have, not just on them, but our entire country. We can’t separate ourselves from Flint. We can’t separate ourselves from Detroit.

And so I think — I’m a firm believer in sort of global reparations, but I do want to sort of specifically talk about Flint and the crisis that exists. And just reading article after article and talking to the community organizers down there, it’s desperate. It’s in these moments where I sort of scoff at the language that we’re living in this “land of the free,” where everything is possible for us. And then you sort of zoom into Flint, and you’re like, “Excuse me?” 60 percent black, mostly poor, and now lead poisoning? I mean, tragic. And so, yeah, I think there’s a huge argument for why that community in particular deserves reparations.

Ms. Tippett: Others?

Audience Member 3: I’m the rector of a small church in Altadena, beginning to wake up and wanting to engage in the work of healing and hope with the oppressed in our immediate community. What would each of you say is the first best step?

Dr. Ross: You go.

Ms. Cullors: OK. I love Altadena. Thanks for being in the room. I think the first best step would be hosting a community meeting and seeing where folks — how this movement, current movement is landing on people. What are people feeling most impacted by in the city of Altadena? What are people’s needs? We have a Black Lives Matter chapter in Pasadena who’s doing great, great work, and I know that you’re neighboring cities and towns, and it would be good to even maybe have, like, a community meeting with Black Lives Matter Pasadena members who is interested in having a broader conversation.

I’m a big fan — I think part of what I miss the most in the work — because I don’t get to do it as much as I used to because I live on a plane most of the time — is sitting with people and just listening and listening to what folks care about the most, what needs aren’t being met, and take it from there.

[music: “Merlion” by Emancipator]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, at the California Endowment with its president Robert Ross and Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors. We’re taking questions from the invited audience of non-profit and social change leaders.

[music: “Merlion” by Emancipator]

Ms. Tippett: There was one more.

Audience Member 4: John Lewis will be in town, I think, tomorrow, attending a prayer breakfast. And if you had an opportunity to meet with him prior to his address, what would be one thing that you would praise him for? And then what would be one thing that you would ask him to do or to say or to address?

Ms. Cullors: I want to meet him. [laughs] I would praise him for setting such a remarkable standard for what it means to show up for black life during his lifetime and his ability to stay the course. Yeah, I think that would be, like, “Thank you.” Like, deep, deep gratitude. And then the second thing I would ask for is, “Come train us.” I think people think that Black Lives Matter leaders and members don’t want to be — want mentors. We do. We want mentors. We want elders that were part of the Civil Rights Movement to train us. We don’t want them to tell us what to do, but we want training. We want to be talked to. We want to be in conversation.

I had the pleasure of meeting with Sekou Odinga in a similar intergenerational conversation, the brother that was incarcerated from the Panther party. He was incarcerated when Assata Shakur was incarcerated. And it was one of the most beautiful exchanges, and it was just us looking at each other and him being like, “Thank you,” and me being like, “Thank you,” and dropping some wisdom specifically around surveillance and the role surveillance played in his movement, and now it’s playing in ours. And we need deep mentorship, and I would love if the older generation would show up for us in that way.

Ms. Tippett: That’s a wonderful question and a wonderful answer. Do you have questions of each other as we draw to a close, anything you’d want to ask?

Ms. Cullors: I have one.

Ms. Tippett: OK.

Ms. Cullors: What has inspired you to be in the work that you’re currently in, and what are you feeling most inspired by, by this current movement?

Dr. Ross: I’m a very patriotic American. OK, I understand that patriotism has been ideologically handcuffed these days. But I love the idea of this nation and its promise. And for those of you that — I’m going to take you back to maybe a painful moment when you were in college and you had to read Democracy In America by Tocqueville.

[laughter]

Dr. Ross: It’s like, “Oh my god.” But in the last third of Democracy In America, Tocqueville describes — and it was interesting because he’s this French sociologist. He comes to America in the 1800s, and back then, in Europe, monarchs and kings and queens ran stuff. The people didn’t run anything. And so he comes to America saying, “What’s up with this?” And ostensibly, he comes interestingly to study our prison system, which is another interesting tidbit.

And he gets — OK, there’s a president, and there’s a Congress and — remember the three branches of government from high school Civics 101 that we all learned. And then he recognizes there’s this thing that happens off the org chart that’s pretty powerful, where Americans come together and using their voice — come together to solve problems through executing on their own agency. And they don’t wait for permission from the king or the queen or even the Congress to do it.

And so what keeps me going is when I see and we see the most marginalized, the most oppressed, the most stigmatized exercising agency and voice and power to change systems. That’s pretty heady stuff. That’s spiritual, right? That’s — I mean, I go to church on Sunday, but I go to church when I visit the organizations we support. So, for me, that has been inspiring, is inspiring today, continues to be inspiring for me.

Ms. Tippett: I was gonna ask a final question, which Dr. Ross has just answered, which is what makes you despair, and what gives you hope right now? And when you talked about trauma, that was your despair, and you’ve just given us this really beautiful moment of hope. And so Patrisse, I want to end by asking you right now, in this moment, what makes you despair? Where are you finding your hope?

Ms. Cullors: I think the despair is definitely in knowing that we aren’t currently living the dream that we have dreamt for black lives that — I think there was something I put on social media the other day that it’s intense when the very movement you started isn’t necessarily translating to supporting your own family. When you’re fighting the criminal justice system, and your nephew just caught a case — 18-year-old nephew, just turned 18. We successfully were able to keep him out of juvenile hall, but now he just caught a case, and it’s hard. It’s difficult, and it tugs at me. What else could I be doing? What more can I be doing?

But the hope is — for me, the hope lies in the movement, the mass movement, the folks who are unapologetic, and our love for black life and black people, our consistency. Folks did not think we would last this long. I think people are now being like, “Oh, I guess we really got to deal with these people.” And that feels good. [laughs] I joined this work because I was angry and depressed and did not feel hopeful, and it was in this work where I found a deep sense of faith and resilience and possibility.

And so my nephew can catch a case, but he knows that his auntie is not gonna let him go out like that. And so we bring our community together to help raise money so he can get a private attorney, so we can fight as much as we can fight and get him the best deal possible. And then we show up back on front lines and try to fight bigger enemies. And so literally, my hope comes in this fight. I think I always have — everything becomes a campaign to me, whether it’s in my family or in my life. I’m like, “How do we make this a campaign?” And I think those tools have been absolutely necessary for my own health and wellness.

Ms. Tippett: It’s been a great honor and also very nourishing to be part of this conversation today. Bob, you spoke a minute ago about being our best selves, and culturally, we’re a lot better at dwelling on what’s going wrong, but we want to be called to our best selves. And the work you’re doing here is aspirational, and Black Lives Matter is aspirational, and so I just want to thank you for being part — and I’m really — thank everybody in this room because I think everybody in this room is part of this work of calling ourselves and our communities to their best, and in so doing, helping make that happen. So thank you.

Ms. Cullors: Thank you.

Dr. Ross: Thank you, Krista.

[applause]

[music: “Distant Street Lights” by Codes In the Clouds]

Ms. Tippett: Dr. Robert K. Ross is president and chief executive officer for the California Endowment. Patrisse Cullors is a co-founder of Black Lives Matter and is the Founder of Dignity and Power Now. She is currently touring with her multimedia performance art piece “POWER: From the Mouths of the Occupied.”

[music: “Distant Street Lights” by Codes In the Clouds]

Staff: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Bethanie Mann, and Selena Carlson.

Ms. Tippett: Special thanks this week to Mary Lou Fulton, Barbara Raymond, Jeannie Weaver, Sue Ko, Joey Bravo, Evangeline Reyes, John Manalili, and all of the great people at the California Endowment.

[music: “Runnin’” by Live Footage]

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoe Keating. And the last voice you hear singing our final credits in each show is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.