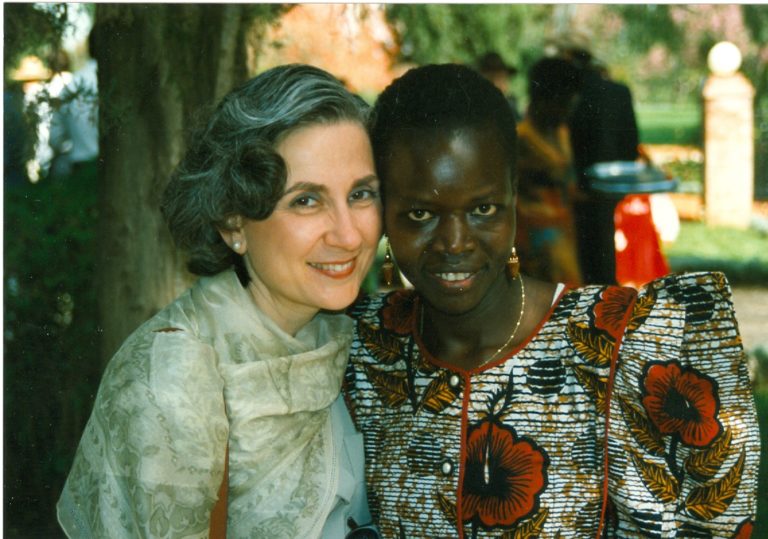

Photo of the author's mother with one of her former students. Image by A.E. Lefton, © All Rights Reserved.

Song of Ourselves: Notions of Womanhood on International Women’s Day

“…these girls are the rightful heiresses of the bygone women who wore beautiful, heavy crowns.” ~Rainer Maria Rilke

What is a woman? And what “beautiful, heavy crowns” are worn by the girls and women of today?

I have heard and read the answers — such beautiful, contradictory answers — given mostly by men. The three answers I think are closest to the truth were written by men who speak in the language of poetry and the sacred: Rainer Maria Rilke, Walt Whitman, and Teilhard de Chardin.

In Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke writes of the evolution of womankind into those “girls and women whose name will no longer signify merely an opposite of the masculine, but something in itself, something that makes one think, not of any complement and limit, but only of life and existence: the feminine human being.”

Teilhard de Chardin, in his essay “The Eternal Feminine,” speaks in the voice of Inspiration, the female counterpart of Creation:

“I open the door to the whole heart of creation. I, the Gateway of the Earth, the Initiation.”

Similarly, in “I Sing the Body Electric” Whitman addresses women as the doorway to both physical and spiritual worlds:

Be not ashamed, women—your privilege encloses the rest, and is the exit of the rest;

You are the gates of the body, and you are the gates of the soul.

When I read these words, the pain of finding one’s voice, identity, and confidence are stripped away and the essence of womanhood shines out. Yet even in these writings, which represent the very pinnacle of male descriptions of the female, there is a lack.

There is a lack because, for all its intense beauty, their prose is abstract, elevated, mystical, and not, at the same time, paired with that very particularity and red-bloodedness that gives history its long succession of “great men.” Their women are the essence of life itself, yes. But they are not living.

To strike a balance between the social and political necessity of writing real women back into history, and the spiritual reality of the “feminine human being,” is something I hope new generations of writers, male and female, will attempt. I believe women will hold our heads higher, despite the heaviness of our crowns, once we begin to see ourselves the way Rilke and Whitman saw us — but grounded in the good earth of our own lives.

In one sense, there is no clear answer to the question, What is a woman? Or rather, there are as many answers as there are women in the worlds of today, yesterday, and tomorrow. At the same time, I feel there is some urgency to answer this question now, or at least to provide the foundation for an answer, because of all the pretend, impossible, and dangerous “answers” media and society are offering our daughters as truth.

If we live in a fractured world, then women reflect the most broken part of it — the most vulnerable, shattered lives. At the same time, women hold the seed of unity, like a sliver of broken mirror that cannot help but reflect a whole, unbroken landscape.

I feel these twin forces at work in myself. It is as if I were both the crushed mirror lying in the street, and also the woman who leans over to see her own jagged reflection multiplied — her own identity and power multiplied because she is no longer afraid of the worst. She has experienced the worst, and though it did indeed kill her, it also sewed her back up with the waters of life thrumming deep inside her veins.

Isis and Osiris. That is what women are. We carry the burden of the old world cut into pieces inside us. And yet we are healers — self-healers too. Lizards who can sever their own limbs, and starfish who can grow new ones.

And I only allow myself to speak in the same abstract, elevated, slightly mystical manner as the three great men I mentioned earlier for one reason, which is this:

If you ask me, I can tell you, in as much detail as you need, exactly and specifically:

how I carried the broken world,

how it killed me,

and how I am learning — slowly, halting —

to sing myself back to life.

For my mother, Jacqueline Táhirih Lefton, 1951—2010