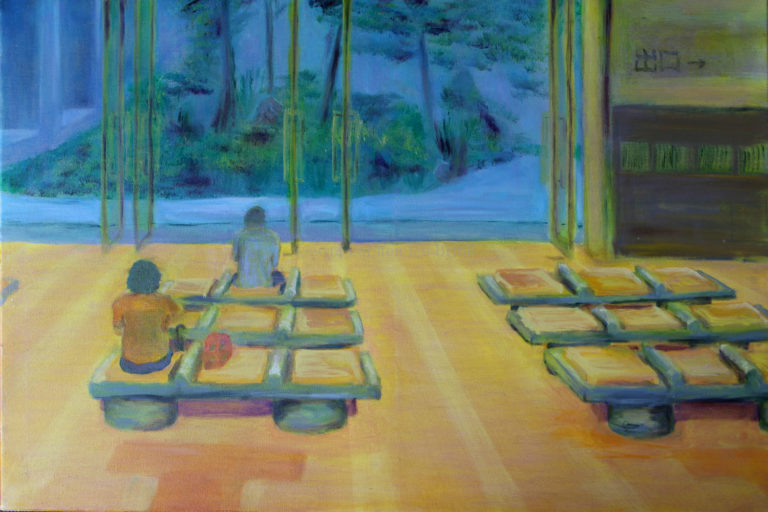

An oil painting of "The Waiting Room" in Japan. Image by Carsten ten Brink/Flickr, Some Rights Reserved.

On Being Mortal: Theological Ponderings on Cancer

After my sister died of melanoma just days before her 50th birthday, I started seeing a dermatologist every six months to have my skin checked for suspicious moles. Each visit carried a tingle of fear, a reminder of mortality. Inevitably there’d be a few pre-cancerous spots that had to be frozen off, the result of an adolescence spent in the sun. On my most recent visit, though, the doctor found two actual cancers. One appeared to be a melanoma, but only a biopsy would say for sure.

The appointment was early on the morning of Christmas Eve, and the holidays meant a long wait for results. January 4th marked the anniversary of my sister’s death, and January 10th her birthday. I thought about all that she had missed in the years since her passing. She had hoped to become a vintner in a midlife career switch. She had missed the weddings of her two daughters, and their growing success in careers of service to the public. She missed the birth of two grandchildren, and was missing the current excitement of a third on the way.

There was about a year between Sheryl’s diagnosis and her death. In that time we saw each other regularly, though we lived on opposite coasts. I remember a Sunday brunch when she showed me the landscape of ridges on the backs of her hands, and shared the hope that another round of chemo would shrink them. I remember most vividly the sunset visible from my desk when I held the phone to my ear, and heard her explain that they were switching to hospice care.

During the long wait for my own test results I made certain not to dwell on a worst-case scenario. From what my doctor said, melanoma seemed likely, so I was prepared for some minor surgery and perhaps the rigors of chemotherapy and radiation. But it also occurred to me that my future might be significantly shorter than I had planned.

I thought of my son, who will graduate high school this year and whom I want to see set firmly on a path to independence. I thought of my partner, whom I love so deeply. I thought of my writing career which is reasonably successful but has yet to encompass that children’s novel I’ve been planning since adolescence. Mostly I thought about death itself, what it entails, what happens after. I had seen it up close, not just in Sheryl’s last days but with both parents and with a dear friend, all victims of cancer.

In the last week’s of my mother’s life, when she was still lucid, I asked if she was afraid of what lay ahead. She said she wasn’t, so I asked if she was curious. She said, “I’m more curious about what came before than about what comes next.” It’s a lovely response with its casual assumption that life is truly eternal, that it precedes mortal existence just as surely as it follows.

Boris Pasternak nails the idea in his novel Doctor Zhivago. I read the passage aloud when we scattered my mother’s ashes on a riverbank in the High Sierra:

“But all the time, life, one, immense, identical throughout its innumerable combinations and transformations, fills the universe and is continually reborn. You are anxious about whether you will rise from the dead or not, but you rose from the dead when you were born and you didn’t notice it.”

Years after my mother’s death I understood the full impact of such a belief. In New York, on a crowded street, I suddenly wondered if each person rushing along the sidewalk was an eternal being. The personal responsibility in such a situation seemed suddenly enormous. All of us on an eternal path. All of us learning and growing and failing and getting up again and moving forward. All of us sacred.

Such thoughts were a comfort as I faced the possibility of a serious health crisis. But theological ponderings come up short in the wee hours of a sleepless night. What if this is it? What if the assumption that I’m on an eternal journey towards ever-greater enlightenment is a fantasy? What if oblivion awaits?

My fears felt vaguely ridiculous when reports came back of squamous cell and basal cell tumors. This was good news, with survival rates in the high 90 percentages. But my brush with mortality wasn’t over. Both tumors had to be removed through outpatient surgery that involved a full day of cutting, lab testing, and cutting again. The procedure is unpleasant, but the waiting room offered some profound lessons.

Between rounds of cutting, with temporary pressure bandages protruding from my jaw, I made notes in my journal about my fellow patients, all there for the same day-long procedure:

There’s one woman who’s clearly in the midst of chemotherapy and spends much longer sequestered with the doctor than the rest of us. She’s reading a book called Love Poems to God. I expect we’d have stuff to talk about. And she’s inspiring in her calm, and her constant smile.

There’s a married couple in their 60s who are very stylish in a suburban kind of way. They watch people then whisper to each other and smile, not unkindly I think. She joined him once when he went back to the surgical rooms but returned before him and seemed on the edge of tears.

One woman, about my age, only just arrived. The receptionist joined her in the waiting area and they caught up on their different cancers, sitting opposite me. The patient had refused an MRI and hospital stay the night before to be home for her son’s 12th birthday. The receptionist — a warm, welcoming woman — recently had a PT scan that showed a return of cancer. She was frustrated because her hair had only recently grown back, but she turned to me and said, “How are you doing, Mr. Norman? It’s a long day, isn’t it?”

The self-dramatizing concerns of the preceding weeks seemed lightweight in contrast to the burdens these strangers were carrying, and carrying well. My comrades in the waiting room were also a reminder that, while my prognosis is good, greater dangers lie in wait, as they do for all of us.

In the end, I don’t think it matters much whether we conceive of life as eternal or as bounded by the events of birth and death. Either way, we must treat it as the precious experience that it is. For me, the lesson is one of awareness and observation — to look at a partner, child, or friend and see them fully, rejoice in them, laugh at the beauty of them. The same is true for clear skies, gathering storms, Redwood trees, bad drivers, potholes and humidity. Also, it’s time get to work on that children’s novel.

Share your reflection