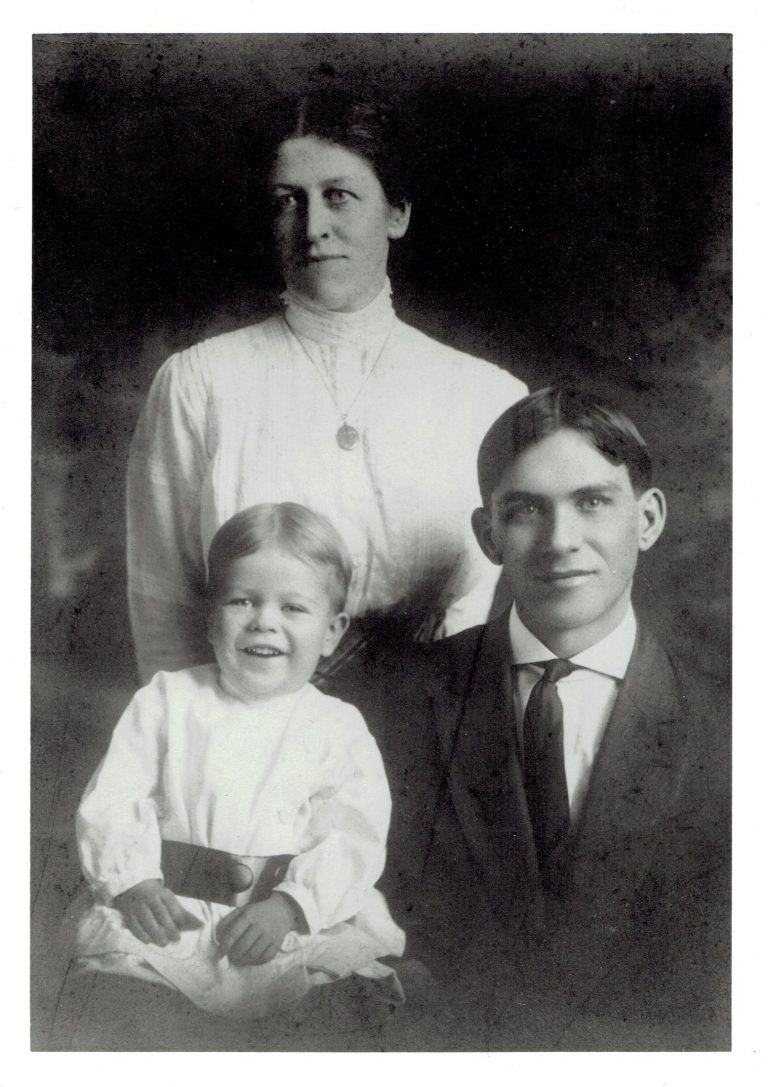

Max J. Palmer at age 2 with his parents (1914). Image by Parker J. Palmer, © All Rights Reserved.

A Left-Wing Son Celebrates His Republican Dad

Father’s Day this year launched me on a trip down memory lane. My father, Max J. Palmer, died at age 81 in 1994. But even today, I think about him frequently, wishing I could get his advice or share some news of my life. Put simply, Dad was the best man I’ve ever known.

I know people mean well when they say, “He’s in a better place now,” but please don’t say those words to me. As far as I’m concerned, the best place for Dad is right here, where we could sit together and talk and laugh. This year, however, I realized that he’s in a “better place” at least in one respect. As an Eisenhower Republican, he doesn’t have see what’s become of his beloved Grand Old Party, to say nothing of American politics in general.

In case you’re not up on what the GOP stood for in Eisenhower’s day, the 1956 Republican Platform pledged to provide federal assistance to low-income communities; protect Social Security; provide asylum for refugees; extend the minimum wage; improve the unemployment benefit system so it covers more people; strengthen labor laws so workers can more easily join a union; assure equal pay for equal work regardless of sex.

Dad rarely talked about party platforms and partisan issues. He wasn’t a policy wonk or an ideologue — and if he had been, I doubt that his convictions about the good society would have made an impression on me. Instead, he had a set of on-the-ground values rooted in his life story — values with personal and political implications that hold sway over his left-wing son to this day.

My father was a blue-collar kid from Waterloo, Iowa. His father, Jesse Palmer, who married Jennie Parker (all three pictured above in a photo taken in 1914), was a machine tool operator who made parts for John Deere tractors. At age 19, at the start of the Great Depression, Dad took a train from Waterloo to Chicago looking for work. For days, this young man with his high school diploma in hand stood in long lines of job-seekers.

Finally, he got a two-week job as a bookkeeper with a firm that sold chinaware and silverware for commercial use. Two weeks stretched into a lifetime with the same company — and that temp job morphed into salesman, vice president, president, owner, and chair of the board.

Because of Dad’s business success, I grew up in an affluent Chicago suburb among the well-to-do. But Dad was determined to raise my sisters and me with the same values he’d learned from his blue-collar family in Waterloo, Iowa — values that contrast sharply with dystopian distortions that drive politics today.

Dad rarely spoke harshly of anyone. But every now and then, he’d say of someone in our community, “He knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” I doubt that he knew he was quoting Oscar Wilde, but those words come to mind often these days as I learn of yet another executive order that will ravage our air, water, wilderness areas, public health, and planetary well-being.

One time we drove by a mansion with a fleet of pricey cars in the driveway. As we kids exclaimed over this spectacle, Dad said,

“I guess you think those people are rich. I’m sorry to say that they’re up to their eyebrows in debt — they can’t even pay what they owe my company. Don’t be fooled by appearances, and never try to put on a show. Not all that glitters is gold.”

Dad wanted to give us X-ray vision to see through the myriad illusions about money that our culture promotes. To this day, I’m astonished by the number of people who believe that owning and flashing bling is a sign of success in business or any other field — or that it qualifies a person to lead a democracy.

When I turned 13, Dad insisted that I get a full-time summer job. While most of my friends were lounging around the pool at the country club — to which we did not belong — I spent several summers caddying for their fathers on the club’s golf course. Later, while my friends were tanning on the Lake Michigan beach, my summers were devoted to cleaning public toilets at the beach house, a job that takes true devotion.

Dad didn’t want me to feel “entitled.” He wanted me to learn how to work, earn and save money, and — most important — to be as generous as he was with people in need. “From those who have been given much, much is expected,” he’d say, a Biblical and poetic way to advocate progressive taxation as well as private philanthropy. He always added that generosity is its own reward, many times over. I now know that he was right about the “return on investment.” What I don’t know is how that reading of the Bible got lost.

Under Dad’s direction, his company instituted an anti-nepotism rule, in part to keep the business free of family interests and needs, and in part to compel me to find my own path. This was a huge gift in a community where many sons never had to figure out what their gifts were and how they might best be expressed. They simply followed their fathers’ footsteps into lives that may have been lucrative but, in many cases, weren’t their own.

Dad also used his company to help people who were on hard times. His logic was simple: this country had given him a chance to pursue his dreams, so he needed to “pay it forward” by passing that gift along to people who’d been less fortunate than he. So sometimes he didn’t hire “the best and the brightest,” but brought on someone who needed a lot of mentoring in order to succeed.

One of those people was a truck driver named Dusty who had grown up in poverty and been used and abused by life. Dusty was sincere in his desire to work, but didn’t yet have what it took to hold a job. Dad suffered through many Dusty screw-ups — traffic tickets, late deliveries, or something of the sort — but never gave up on trying to teach him good work habits.

At dinner one night, I heard yet another story about how Dusty had gotten the company into trouble. I was a know-it-all teenager, so I said, “Why don’t you just fire the guy, Dad? He causes you so much trouble!” My father nailed me with a stare that would have frozen a zombie in his tracks. “But, Park,” he said, “Dusty has a wife and two children. Where else would he get a job?”

It took me years to realize that the “Dusty stories” Dad told at the dinner table were as much about us kids as about Dusty. He told them to help us understand that we are put on earth to help each other.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad! I love you, and I have never stopped drawing on the legacy of personal and political values you left me. Along with a lot of other folks, Republicans and Democrats alike, I’m trying to keep the faith in a country whose current “leaders” know the price of everything and the value of nothing; have deluded a lot of people with fool’s gold and sleight-of-hand; put self, family, and cronies ahead of the common good, and are bereft of the generosity that helps create the Beloved Community.

Once upon a time, long ago and far away, there were citizen-leaders of a different stripe. Someday, I pray, they will make a comeback. In the meantime, I’m grateful beyond words to have been raised by one of the best.