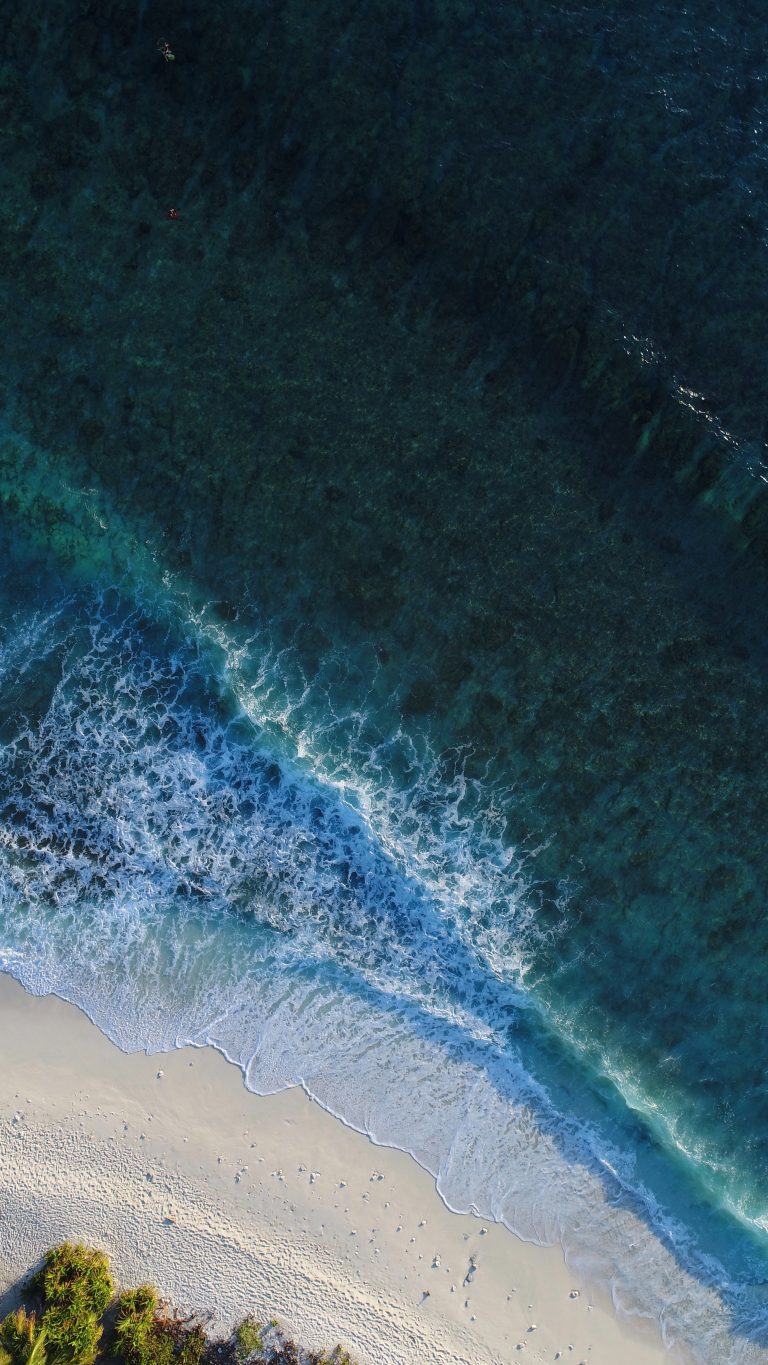

Image by Shifaaz Shamoon/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

We Should Never Have Called It Earth

We should never have called it Earth. Three quarters of the planet’s surface is saltwater, and most of it does not lap at tranquil beaches for our amusement. The ocean is deep; things are lost at sea. Sometimes we throw them there: messages in bottles, the bodies of mutinous sailors, plastic bags of plastic debris. Our sewage.

Sometimes the things we lose slip unnoticed down the sides of passing ships. We expect never to see lost objects again, but every so often they are carried by shifting currents and swirling eddies to wash ashore on distant beaches. We are reminded that things, once submerged, have a habit of returning.

I am not afraid of the ocean, although I should be. On hot summer weekends I take my son to the beach. He toddles toward the water, laughs at the lazy waves splashing his fat baby legs. I follow behind, turn him back when the water reaches his naked belly. He is too young to know the sea gets deeper, that eventually it rises above your head and you must swim so as not to drown. I am prepared for nightmares as he grows and learns about the vastness of the ocean and the monsters real and imagined that swim there. He will soon know that evil things lurk in the deep.

I am a climate scientist, a computer modeler studying the things we put in the atmosphere. On first glance, my work seems confined to a realm wholly above and separate from the underwater world. But the ocean and the air are the great conspirators of our climate. The motions of the atmosphere, the rise and fall of air above us, are dictated by the temperature of the sea surface. Much of our weather is shaped by the back-and-forth slosh of water in the tropical oceans.

Some years, around Christmas, the waters of the Eastern equatorial Pacific become abnormally warm. This El Niño, an imaginary visitation from the Christ child, feeds violent tropical thunderstorms above the warm pool of water. The tropical East floods; drought comes to the West. Indonesia and Australia burn.

The atmosphere is listening, and it carries the sea’s messages far afield. The trade winds weaken, barometers measure drops and rises in pressure, and air currents are re-directed. El Niño brings rain to the American Southwest, mild winters to southern Canada, reduces hurricanes in the north Atlantic. The average temperature of the entire planet increases. We, all of us, are at the mercy of the ocean.

Before we existed, and after we are gone, the ocean will continue to whisper to the atmosphere. Weather patterns will change back and forth with the natural oscillations of air and water. But we do exist, and we are treating the atmosphere as a limitless dumping ground. A signal of our handiwork is emerging against this cacophony of noise. Things are changing.

Dive into the ocean and there is no immediate impediment to progress. At some point your ears pop. Stray too deep or too long and gases make bubbles that pop in your joints. To dive into land requires mechanical assistance: dirt beneath fingernails, shovels in sweaty hands, a screw turned by internal combustion. Deep in the ocean you may find a wrecked ship, tarnished gold, dissolved clothing threaded through buried skeletons. Deep in the earth we find fossils, the compressed detritus of primeval death. Burning these gives us light and energy and heat. Some of this is deliberate and localized. Some, however, is not.

We find greenhouse gases difficult to understand. Accepting that gas means danger is a sad condition of modernity. But we imagine rancid air that tickles then chokes, yellow clouds on a battlefield in Flanders. We accept that burning is warmth, but that its byproducts may linger and mix without color, odor, or taste seems too strange. Linger they do though. They trap the thermal effluence of the planet and, in so doing, warm the planet.

The warming is not immediate. Delays are built into the system: there are different forms of inertia here. The air warms first, then the land, then surface winds mix the shallow surface layer of the sea and finally the abyssal reaches of the ocean. The heat slowly trickles down to the deep, churned by slow overturning ocean currents. The ocean is slow to warm, but it will receive the message in time.

Someday I must tell my son what I have done. My comfortable, safe life is in large part a product of the internal combustion engine. Fossil fuels power the trains that take us to the beach, the factories that make his plastic bucket and spade, the lights I switch off when I kiss him good night. We can make small adjustments: recycling, buying reusable bottles for our water and ice coffee, foregoing the occasional plastic bag. But these small things, even multiplied by a large population, are still small in the end.

I cannot deny my son or myself the ease of modern life, and I have no wish to isolate him from friends and family by insisting on radical changes. A carbon-free life seems a solitary one: no travel to see grandparents, awkward refusals of invitations, precious time with friends replaced by gardening, canning, mending, building, working. I search for political solutions, an advocacy muted by the cowardice of my personal choices. In the end, I am responsible for the gases that are changing the climate and, in raising my son in comfort and convenience, am passing on that responsibility and guilt to him.

Greenhouse gases are indisputably warming the whole planet. We are moving toward a future where the natural variations of El Niño are swamped by rising ocean temperatures. There will be no weather that we have not somehow touched. And our legacy travels deeper than we think: We have left to our children a time bomb of warming. Even if we somehow managed to halt the increase in greenhouse gases, freezing them at today’s levels, the planet’s temperature would continue to rise as the heat trickles into the deep, slowly creating a new equilibrium. The ocean will eventually know what we have done to the atmosphere. The process is slow, but inexorable. We have committed ourselves to this warming, a legacy to future generations.

To be a climate scientist is to be an active participant in a slow-motion horror story. These are scary tales to tell children around the campfire. We are the perfect, willfully naïve victims: We were warned, and we did it anyway. Dark fairytales, of course, are as old as human history, and we tell them for a reason. But here, the culprit is the teller, both victim and villain.

The moral of this fable is murkier than the simplicity a children’s tale demands. At the end of the story, the fear persists. We continue to burn fossil fuels and the gases they make continue to trap heat, warming the air, the land, the shallow seas. The heat is mixed deep into the ocean, a long slow slog to equilibrium. There is no way to stop it.

What do I tell my son? A monster awaits in the deep, and someday it will come for you. We know this. We put it there.

Share your reflection