Darnell Moore

Self-Reflection and Social Evolution

Darnell Moore says honest, uncomfortable conversations are a sign of love — and that self-reflection goes hand-in-hand with culture shift and social evolution. A writer and activist, he’s grown wise through his work on successful and less successful civic initiatives, including Mark Zuckerberg’s plan to remake the schools of Newark, New Jersey, and he is a key figure in the ongoing, under-publicized, creative story of The Movement for Black Lives. This conversation was recorded at the 2019 Skoll World Forum in Oxford, England.

Image by Paul Stewart, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

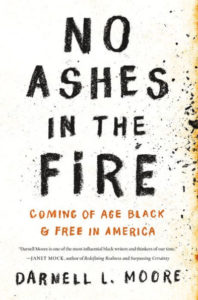

Darnell Moore is the Vice President of Inclusion Strategy at Netflix. His memoir is No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black and Free In America, and he is host of the podcast “Being Seen.”

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Darnell Moore embodies, for me, an emerging story we’ve barely begun to tell ourselves about new understandings of change and healing in this young century — the self-reflection that goes hand in hand with culture shift and social evolution.

Darnell Moore: I don’t want to become a better man, because you all know, what I’ve been told manhood is, it’s not anything I’m trying to aspire to. I want to become a better human person. And if we can help people journey to that place, we might find ourselves holding onto the keys that can unlock the cages that are keeping so many of us who have been identified, or identify as men, are socialized into manhood — freedom might be on the other side of that. So I talk about un-becoming — not becoming a man, but what it might mean to un-become: our failing at this project, this cage, these ideas of manhood that have been mapped onto us. I think to me that is where our freedom lies.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Darnell Moore tells the story of his formation in his book, No Ashes in the Fire. He’s grown wise through his work on successful and less successful civic initiatives, including Mark Zuckerberg’s plan to remake the schools of Newark. And he is a key figure in the ongoing, under-publicized, creative story of Black Lives Matter. He joined me in a room full of social entrepreneurs at the 2019 Skoll World Forum in Oxford, England.

[applause]

Ms. Tippett: Thank you. So happy to be here. We’ve wanted to come to this forum, and this is the year it was possible. And to be here with Darnell Moore is really exciting. So I’m just gonna jump in. We will be in conversation up here about 35, 40 minutes. I’ll invite you at that point, if you have questions, to hand them wherever people are showing you to hand them. And then we will do a bit of a back and forth, open the conversation up to the room, and then we’ll come back up here for the last five to ten minutes, because we’re doing this for radio.

So I’m just gonna leap right in. I want to say, this is a very beautiful book, No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black and Free in America. Highly recommended.

Darnell, I start most of my conversations with a question about the spiritual or religious background of someone’s childhood, however they would describe that. And that can mean so much more than religious formation. It can be what was happening with your body and spirit. And as I read your book in particular, there’s a word you use a lot, which is kind of a magnetic and surprising word, which is “magic.” You talk about “the everyday, ordinary magicians who learn to create life among death-dealing cultures of hatred and lies.” So what is that magic, as you’ve experienced it in your life?

Mr. Moore: Well, first, it’s magic to be sitting in a conversation with you. [laughs]

[laughter]

It’s so funny; when you say that, the first image that comes to my mind is the black family I grew up around, people who lacked, according to all standards, a type of wealth. Yeah, they didn’t have a lot of money. But they were in possession of a lot of love and care. And if I knew nothing else, I knew that the people around me, even though media and the larger world tended to characterize the people who I called family, the place that I called home as “the ghetto,” as “the hood,” as almost lacking virtue — here were people that made something out of nothing. I talked to somebody earlier and said, “It’s the type of family where you will look in the cupboards, and as a child, I didn’t see any food. How did they make this full dinner?” But they made something out of nothing.

All that to say, that’s how I live my life. I live my life as a sort of dreamer, always thinking about how I would, and could, pull from whatever sort of resources or love that I had, to make something of a life.

Ms. Tippett: You start your book with — talking about another use of the word “magic,” a “childlike magic.” And you focus that — we see a picture of you, a picture of your face in which that phrase is absolutely — comes to life, is evident. You wrote, “It took years before I realized the image in my mama’s picture was beautiful. With skin too brown, big lips, and a wide nose, I often turned away from my reflection. As I grew up, there were invisible forces moving about like ghosted hands. A hand would touch my cheek and steer my head and eyes away from the mirror. It was unseen, but felt, and it needed to be named.”

I feel like that’s such an apt image for this moment we inhabit together, where there’s this naming of things that have been true, but many of us could turn away from them and even make others turn away from themselves.

Mr. Moore: I’ve been thinking about this moment. We’re a culture that’s been taught to lie and to love lies. We are, I think, within a moment that is asking of us — so many of us are pointing fingers at the big monsters in the room, whether that’s within a range of movements that are centered on rape culture and sexual assault, or racism and such. But no one ever really takes the time to think about what it might mean to point the finger back at self and examine the monstrosities within us. So self-reflexivity, self-reflection, honest reckoning, is something that we do not like. A big part of my writing in the book was, I really wanted to model — even beyond modeling, I just wanted to be honest and say, “It’s gonna be impossible for me to talk about my dad and all the things that he did and all the ways in which he showed up as a monster in my life” — or the world, or homophobes —

Ms. Tippett: And your dad was in and out of jail, and —

Mr. Moore: He was.

Ms. Tippett: And he was a person who could be incredibly loving and tender to you and, also, could hurt your mother.

Mr. Moore: Absolutely. And I tried to write about him in a complex way, but I also realize that to turn to self, and my need to also think through the ways that he and I were shaped by same sort of forces, was really critical. It was really healing for me. The reason why I was able to forgive him for all that I observed and witnessed him doing is because I finally realized — when I realized that the distance that I thought that existed between us, the moral distance, [laughs] was quite short.

I didn’t physically abuse girls and women in my life, but I certainly was privileged to go out into the world and be free, because I was the oldest boy. I was never questioned about things that I wanted to do in life in ways that, say, my sisters were. And I kept thinking, “Oh, so I benefited from patriarchy,” these words we like to use; “I benefited from this position of maleness in the same ways that he did.” And it’s just really important, I think, for me — it was important; it is important, for me — to reckon with self.

But isn’t that how we get to transformation?

Ms. Tippett: Yes, and what feels important to me, too, is, even when you begin with the picture of you as this beautiful, beaming child …

Mr. Moore: Thank you.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Yeah — and you’re still beautiful. This picture of you is — your quest for this, for self-knowledge, for justice, for us to tell the truth and free ourselves from the cages these lies have put us in, is about recovering joy. You want to recover that smile you had on your face as your birthright — and, actually, as all of our birthright.

Mr. Moore: It’s so funny — I had gotten so used to believing that my childhood lacked smiles, because that’s what trauma does. The smiles were overshadowed by a lot of the violences that I witnessed. And that makes a lot of sense to me. So I started looking at pictures. In my mind, I just could not remember myself as a seven-year-old kid on a Big Wheel, with socks up to my knees, making dirt sandwiches and mud pies and all this stuff with a big smile on my face, until I looked at the pictures. And I started laughing, because I’m like, “Oh, I did smile.” And then it made me think, how, how, how did that little boy find a smile, maybe the day after watching his mom being brutalized by his father? Or how did a 14-year-old-boy get up and find a smile after being called names by friends or being attacked by friends? And it reminded me of the power that’s — and this is what I mean by magic, again— what it means to summon strength from within oneself, in spite of what’s going on; what it means to be alive and making life possible, and dancing and sweating and enjoying the company of others, even as the fire is burning — which is not to minimize the fires that burn in our lives.

Ms. Tippett: No. But in some ways, we have to take seriously and keep walking towards that joy to stay alive, to stay whole, to come out the other side whole.

Camden, New Jersey is also very much a character in your story. You were born there, right? You grew up there.

Mr. Moore: Yes. Yes.

Ms. Tippett: It was Walt Whitman’s “invincible city.” And when you were growing up, it was a place that journalists would call “the most dangerous city in America.” And you got out. You left and then came back. And you didn’t originally come back because that’s where you wanted to be. And I think — you’re a writer, and you also know how strangely, mysteriously, the more personal you can be, the more vividly personal you can be, the more universal the story becomes. But in this context, I think, also, this story of Camden, New Jersey is the story of cities all over our country and all over the world.

Mr. Moore: Yes, it is.

Ms. Tippett: It seems to me — I want to talk about that too, because when you came back you got involved in some — and this is a room full of social entrepreneurs — really good efforts, but in which people were coming to save Camden, but kind of treating it like a faraway country that they were going to develop.

Mr. Moore: I would’ve loved to tell the story like, “I went back to Camden fired up!” But I didn’t; I was hesitant to go home. I didn’t want to return home, and I ended up having to go back, because nobody would hire me. [laughs] So I was like, “OK, I gotta go back to Camden.” [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Even though you did end up getting those great grades and getting into good schools.

Mr. Moore: I did get great grades. Didn’t matter. I ended up home, and I ended up living in a house as part of what was called an urban ministry, with what they would call urban missionaries. And the other people that lived in this home with me were all white, all of whom had come from other states and other countries to the place that I was running from. The house, you’ll be surprised to know, was literally about three to five minutes walking distance from my mom’s house. And I was just, like, “God, this is hilarious.”

[laughter]

You want to talk about a joke? I was raising my fist to the air, like, “How dare you? Not only are you sending me home, but my mom lives around the corner.”

But I’m so grateful that that happened. I was making — I don’t think that’s called — that’s not a wage, but we were paid a 30 dollar a week, I think, living allowance. So this tells you — so people were opting in to getting paid 30 dollars a week. This tells you the type of — and I’m gonna use the word “privilege” — we use that word and throw it around, but to make a choice like that, to fly into Camden, tells you the sort of worlds that people were coming from. But there was this way that we would go out and do these asks at churches on, like, a Sunday. We would go to the church, and we would talk about the city. People would be talking about the city as if it was this space [laughs] that I didn’t come from, a space that I didn’t know. And I felt woefully uncomfortable with the way that they were able to manipulate the — we call it “trauma porn,” yeah? — to get people to feel. And I was thinking, if I have to go down a list in order — especially on a Sunday service — and lament about what ails communities that we might otherwise know what was happening about if we actually entered those communities — if this is what it takes to get people to feel and, therefore, give money to this urban ministry, then it showed a lack of true care, to me. And that bothered me.

Ms. Tippett: You also, later on — and this is a very different story, but feels a little bit connected, to me — you ended up working on this project that was funded by Mark Zuckerberg to heal the schools in Newark. And I think that was a complicated experience, like this other one; it wasn’t all bad, and it wasn’t all stuff you would criticize. But what did you take out of those experiences about what you think really is needed to actually heal, to actually transform, because those things you experienced didn’t affect that.

Mr. Moore: What I will say is that those same folk, by the way, I felt so critiqued in that moment, because these were the folk that were also providing after-school tutoring and activities to my cousins. So there’s that, on the one hand, but then there are the systemic challenges.

When I was working in Newark, doing school reform work as part of a project that was largely funded by the Facebook/Zuckerberg money, what I learned was that sometimes what we imagine to be our good is not always our best, is not always great. And sometimes the good can be commoditized. So there were so many lessons that were learned from that particular experience, namely, one: anytime that we’re attempting to do community engagement work — and it’s funny that we would call it community engagement work — are working in community with vulnerable peoples and are groups who, I like to say, exist on the edges of the edges of the margins — but refuse to center the very people you say you are in community with, you know you’re starting off in the wrong place.

Ms. Tippett: And what would that look like, to center that?

Mr. Moore: It looks like, before we come in to become the architects of a plan that tells you what transformation looks like, actually sit down with the people and ask them what it is that they need, what it is that they desire, what ails them; what is their freedom dream, as Robin Kelley would say. And so many times, what we do, we fly into communities out of these helicopters, salvific helicopters, with ideas and plans because we’re social entrepreneurs, and we have innovative things to do, and we have used “best practices,” [laughs] and we have tried and tested and evaluated and have evidence-based models. Y’all see where I’m going. And then, so therefore, we can come into the community as “experts.”

That’s what neoliberalism tells us. Neoliberalism is about the dissolution of community, about the lifting up of the big “I,” the expert in the room, never about community-building and the reminder that expertise lies in every one of us; that we all have analyses.

And I think what it looks like, then, is moving ourselves out of the way and creating space for everyone — particularly those we say that we’re in community with, are working on behalf of — to do the dreaming, to be the architects of their own dreams, of their own transformation, of the worlds and the communities in which they’d like to live. And then we journey along with them – never, ever commandeering the journey, which is what tends to happen.

[music: “Caronte” by Anima]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with journalist and author Darnell Moore, who’s also a key figure in Black Lives Matter. We’re with a gathering of social entrepreneurs at the 2019 Skoll World Forum.

Ms. Tippett: Did you know Vincent Harding before he died, the civil rights leader?

Mr. Moore: I did not, but I knew of his legacy.

Ms. Tippett: You knew of him, yes. I kept thinking, when I was reading you and thinking about this of something he said to me, which I’ve never heard anybody say in quite this way. But he was a civil rights leader of a different generation, and you are, you could be called a civil rights leader, a freedom fighter of the next generation of that movement. And he was talking about — he actually took the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement into communities, to young people in hurting places — “What did we learn; what did we know?”

And he talked about experiencing — he was talking about being in conversation with a particular person, a young person, like many other young people, operating in a situation where they felt it was just very, very dark all around them. And what they needed were, as he put it, some signposts, human lights, the live human signposts that would help them see the possibilities for themselves.

And then he said this: “I’ve always felt that one of the things that we do badly in our educational process, especially working with so-called marginalized young people, is that we educate them to figure out how quickly they can get out of the darkness and get into some much more pleasant situation, when what is needed again and again are more people who will stand in that darkness, who will not run away from those deeply hurt communities, and will open up possibilities that other people can’t see in any other way except seeing it in human beings who care for them.”

Mr. Moore: It reminded me of — I was telling you I was running away from Camden, partially because I —

Ms. Tippett: That’s what we do in this country.

Mr. Moore: We run… [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: We run.

Mr. Moore: … particularly because of this notion of — these skewed notions of success, or what success might mean, or this American Dream. But there is something to be said about sitting in discomfort and sitting within spaces of — sitting in the darkness.

I did a lot of work and have done a lot of work with young people, particularly queer, transgender, nonconforming young people, many of whom were houseless — they did not have homes to go to, some of whom had to make various choices about — and negotiate, every single day, about where they’re gonna stay and what they’re gonna do to be able to stay at those places — all of this within this very moment of queer liberation and freedom. And so, so, so many times, I wished I could snap my finger and pull them out of the spaces of despair that some of them were in — and not all were in despair, by the way. So the reason why I talk about queerness is magic is because when I look at the way that these young people maneuver through the world and survive, I see nothing but strength.

But we resist the uncomfortable conversations. I mean, to love is to not lie. I had a friend who once said, “How do you walk in these rooms and say the stuff that you say to white people?” [laughs] And I’m like, “Well, how are we gonna heal, if we don’t reckon with the truth?”

So all that to say, sometimes when I’m having these sort of conversations that — I don’t even think they’re tough, I think that they are honest, and they are signs of love — folk don’t want to be made comfortable. I don’t understand how that can be. Well, I do understand. [laughs] I do understand how how we resist discomfort, but what I do know is that we can only get to “light” if we are willing to work so hard to travel through the darkness.

Ms. Tippett: Right. There’s a way in which, as you say, it’s intuitive to resist discomfort, but it could be a muscle we flex to get stronger.

Mr. Moore: It’s work.

Ms. Tippett: Right; as you say, it’s work. The context, for you, of love, and your point that, in fact, to be honest is an act of love, and the opposite is not — you come back, a lot, to love in the book.

I hear the word, “love,” really rising up, really surfacing societally, and it’s also a ruined word, culturally. So, as those of us who want to use that word — it holds all the complexity, in the way you use the word and the way I’m finding really, really fantastic people using the word. It holds all the complexity that life does and, in fact, that love does, when we — all of our experience of love is complex. It’s funny, because — but when you use it politically, it sounds like a soft option. It’s the hardest thing in life, right?

So when you were working on creating a charter school as part of that renewal of the school system in Newark. And you were designing this Sakia Gunn School for Civic Engagement in 2010, which was — and she was a young woman who was a lesbian and died.

Mr. Moore: She was murdered.

Ms. Tippett: She was murdered. And that project didn’t work, and you describe this moment where — it was a meeting where people were weighing in on it and talking about it; it was “just another form of segregation” was what you were talking about, or they were against “gay schools.” And you talked about how being in that meeting, surfaced all of your personal drama with this, all of your personal hurt. And the thought you had in that moment, and I want you to talk to us about this thought, is: “Americans travel so quickly to the edges of our love.”

Mr. Moore: I forgot I wrote that sentence. [laughs] It’s important just for me to say Sakia Gunn’s name. She, in her life — I didn’t have the fortune to know her, but certainly her death catalyzed a localized movement in Newark, New Jersey. She was murdered at 15. She was a black, lesbian, AG — we call aggressive — identified girl. And it’s important just to name her.

The school was a part of a new plan that was being fleshed out in Newark, a bunch of new, traditional public schools that were organizing around certain themes. And the theme of this school was civic engagement, really helping students to think about social justice. And some of the — not “some,” but a lot of the residents pushed back against the idea, because they thought that we were trying to create a school solely for LGBTQIA students, which, as you know, as a public school, that’s impossible.

Ms. Tippett: Just because it was named after her?

Mr. Moore: I mean, yeah. But what was interesting about it is that some of the people in that room, I had been in organizing with in other capacities. And I was with them in other spaces. But this particular moment, the love that had been extended to the least of those within our community seemed to have stopped right there. And so the way I describe it is — I’ve been in, for instance, marches for, like, Movement for Black Lives. And people out here in it were all organizing and raising our fists. And we’re going in, and we got Black Lives Matter shirts on. And I remember being told, when we talked about remembering that trans women of color are dying, and we should be marching on their behalf — if we can march, marching on their behalf too, someone saying to me, “That’s not — why are you distracting us from our work?” Or me being at the Pride march in queer New York City, as queer as it’s supposed to be, and this is just a year and a half ago, and we’re out there having a rainbow good of a time until the Black Lives Matter protesters come and disrupt the march. And all of the happy folk who are here with me in our Pride outfits are upset, because now the Black Lives Matter folk are “distracting” from “the real work” of Pride. What I’m trying to get at —

Ms. Tippett: Those are the edges of our love.

Mr. Moore: The edges, the very limited ways that our politics are organized around self-interested desires only; the things that “touch us at our homes,” but never, ever the other stuff, as if a Black Lives Matter march is not a queer project, as if Sakia’s life as a queer person is not also a part of what it means to fight for black liberation. And so, we do; we stop right there, which is why I like to be very clear, when I’m talking about love I’m talking about costly love, not cheap, Hallmark-ish love the way that we’ve come to imagine it.

Ms. Tippett: What does King say — “strong, demanding love”?

Mr. Moore: Yeah.

[music: “The First Surface” by Near the Parenthesis]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, I’ll be back with Darnell Moore. And you can find this show again in 3 of our libraries at onbeing.org: Racial Healing, Reinventing Common Life, and Body, Healing, and Trauma. We created libraries from our 15-year archive for browsing or deep diving by topic — for teaching and reflection and conversation. Find all this and an abundance of more at onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with Darnell Moore at the 2019 Skoll World Forum in Oxford. He’s a key figure in the constellation of social energies, including Black Lives Matter, that he and others call the Movement for Black Lives. He embodies a wisdom and courage about the forgiveness, self-reflection, and self-criticism that go hand in hand with social evolution as much as personal growth.

Ms. Tippett: I want to talk about Black Lives Matter. You’re a journalist. That’s one of the hats you wear. Journalism in this country has not really covered Black Lives Matter, I don’t think. And I think it’s partly — well, there are many reasons, some of which are the reasons Black Lives Matter needed to begin in the first place, but some of it is because it doesn’t look like a movement the way that has been defined. And so when there’s a march or a protest, that gets covered. But you said that this is a whole completely different kind of thing. You said, “Black Lives Matter” — this is how you defined it — “is a radical social intervention … And it takes courage to stage a public disruption or act of civil disobedience, but often that is the only type of work the public might see.” And the public also might only see that because it’s the only thing journalists will cover — I’m adding that. “The harder work, though, is that which occurs before and after public works of protest. It also takes tenacity to do all this work without being bought by political machines or donors.”

There’s a way in which, I feel like we haven’t really even started telling ourselves the story of Black Lives Matter the way, 100 years from now, somebody will tell it. And they probably may not remember what a hashtag is, but they may note that it was started by three women, and two of them were queer, right? So I wonder if you would just talk about your experience, what that movement or social intervention has meant to you, how you got into it, and how you see its ongoing force in our world.

Mr. Moore: So I’m grateful for the question. The Movement for Black Lives, or what some refer to as Black Lives Matter, it represents a constellation of groups, including the Black Lives Matter global networks and several others, like Dream Defenders and Black Youth Project and SONG [Southerners on New Ground] and dot-dot-dot … I want to always talk about this particular movement as part of a long history of black struggle within the context of the U.S. I don’t see it as separate from, but a continuation of, a part of a genealogy, an iteration of a movement.

What was really, really key is that — a couple of things. You have some folk who have been involved in this iteration who — I can remember being in conversations where we’re very forthright about ensuring that the typical things, like black, cisgender, male, charismatic leaders, are not solely lifted up as the folk that we ought to listen to. And I’m bringing that up, because that is what media was searching for.

Ms. Tippett: Exactly, that charismatic leader.

Mr. Moore: Everybody was like, “Well, who’s the leader? We want him to look like Martin Luther King,” [laughs] because this is what we have somehow been led to believe that movements ought to look like. But here you have this decentralized, or not even really decentralized, but what folks called a leaderful movement that represented folk who weren’t that. These were women, cisgender and transgender women, queer women; folk who were not walking around in suits, but had their pants sagging; folk who were not preaching behind a pulpit, but who might have been on a corner of their neighborhoods. And it represented something very different, in ways that elided the American way that we’ve come to think about movements, which was its beauty. Which was its beauty.

So we talk about that. We talk about what I call the “spectacularities of movement building”, the stuff that you get to see, the stuff that people want to report about. But what folk don’t see are the ways the communities are built and the stuff that’s happening outside of the camera. It looks like folk showing up for each other and putting money together to make sure that some of these organizers are getting therapeutic interventions for the traumas that they are experiencing. It looks like when the same folk that we lift up and we follow on Twitter, and we put on the cover of our magazines, who we glamorize because they now become somebody who is a spectacle within the media, may not have money to pay their rent, may not even have a place to lay their head, may not even have food. It looks like people coming up with means so that that person can eat. It looks like everyday struggle, not the spectacular stuff, not the stuff when the cameras are there, but what do you do when them everyday “microaggressions” that we may ignore are eating you alive, and you need support?

It looks like when my father died, I didn’t ask the Black Lives Matter New York chapter to come, but they found their way to Camden. And when I’m burying my father, I look over, and you have a whole chapter of people who have become family, who have come from various parts of the country, who showed up. That’s the stuff that we didn’t miss, the spiritual elements of this.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve said that the — so, for you, this started with Michael Brown in Ferguson and driving almost 1,000 miles and being part of working with Patrisse Cullors to create a — I don’t know, what did you all call that?

Mr. Moore: It was a Freedom Ride of sorts.

Ms. Tippett: Freedom Ride. And so people converging from all parts of the country. And you —

Mr. Moore: We brought 500 people. 500 people, plus, came that weekend, and this precipitated what would be the development of the Black Lives Matter global network. So those folk were encouraged to think about, not only Ferguson, but the other Fergusons; that is, the homes that they were gonna go back to and how they could take that energy back. So that really catalyzed the development of what is now the BLM network. And to be part of that development process was life-changing in so many ways. We did not intend, when we were trying to get people over the course of two weeks to travel across the country and show up together as caravan to support the folk in Ferguson — I should name, here, that people didn’t just show up there. We actually worked, over the course of that two weeks, to ask folk there what it is that they needed — if they even wanted us to come. And we were — so many of us were changed for that. And I think the culture was changed, for that.

Ms. Tippett: You did say, you did write. “What I wish I could adequately detail, though, is the spiritual undercurrent” — and here we go — “the radical black love that flowed that weekend.” And I feel, also, that’s not part of the story — that’s not vivid on the outside, because it also gets covered as a political movement, with a very clinical, technocratic, 20th-century lens on what a political movement is about.

Mr. Moore: It’s so true. I’m laughing. You see me smiling, because I forgot that I said “radical black love,” and I was once in conversation with bell hooks, and she said, “What do you mean, ‘black love’? It’s love. Love is love.” And I said, “No, black love.” [laughs] And I told her I had to modify that, precisely because, for black people within the country who said that it loved all people, [laughs] to think about love as anything that is not politicized, for some, is to lie. So, I say black love because I know what it means to exist in a space, in a nation-state that espouses love and says it loves black people, but its history attests to something very different.

Black love, to me, and I talk about this in the book, is exampled by my family. I write about our house being always packed and always full, and people laying on couches and going to sleep on floors and three to four in a bedroom and everybody at a table, play-cousins, people I never met before who became cousins; but the idea was, anyone who ever showed up at our door, who knocked on the door and was in need, my people let them in. They never disposed of folk.

When we say — we always say, when we were talking about “black lives matter,” we were talking about all black lives and all aspects of black people’s lives. And to talk about lives without attending to all of those things is to do a job that is not just.

Ms. Tippett: I also find, in your own work and writing, you apply that reflection to yourself. You’ve gone through really hard times. You went through 20 hard years. You made a suicide attempt, and it had to do with sexual orientation and identity, but not just that. I don’t know. I’m gonna read this, just because I think it’s such an amazing description of depression, which is also too simple a word.

“I wanted to feel the sun’s warmth on my face and be overcome by the light, but life felt cold and appeared dark. The run was endless. My body and mind were exhausted because I could never grab hold of the light. I now wonder how many black boys and men walk under dark clouds every day, hoping to appear closer to the stereotypical images of success and masculinity so many of us are taught to emulate. It wasn’t that I was too weak to simply think differently or give a middle finger to hateful people. I wanted to die, which is to say, not live, which is to say, not have to be strong enough all the time to fight to exist, which is to say, fight at all, which is to say, I really want to live without having to fight so damn hard to exist.”

Mr. Moore: That’s the first time — I’m just, water in my eyes, [indistinct]. I don’t think — I’ve not heard — I’ve done a lot of book talks; we’ve never touched that passage. So it had an impact on me, hearing it just now.

But I’m really, also, thoughtful, not only about the individual stakes, how we are impacted as individuals within the world, but I often think about the ways that we also are not allowed, as a collective, as people, to wrestle with our sadnesses, to be honest, even those of us who believe that we are to be so strong, especially those of us who show up in rooms like this, when the reality is, so many people suffer these everyday types of darknesses. And so many suffer alone. And I’m just thinking about why it was important for me to write that: because I needed someone to pick it up and to know that it is OK for us to not be OK. As simple as that. And that simple acknowledgement, I think, can be a doorway to healing, for so many people.

[music: “Sky Blue” by Peter Gabriel]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with journalist and author Darnell Moore, who’s also a key figure in Black Lives Matter.

Ms. Tippett: I wonder if you would tell the story of being with your father when he was dying, and the last words you spoke over his body. He was unconscious, but you were with him.

Mr. Moore: My father passed away while I was writing this book — at 55, which is important to note; black men dying very early is a thing. And I often say he died of heart issues, both metaphorical and literal. So you have a sense, from what we talked about, that our relationship was very strained. And growing up, I was the only son, the oldest child. And there’s a way that the only son, the oldest child, [laughs] in this patriarchal way of thinking, “Dad dies; you better be ready to take up the mantle.” So I would say things like, “When he passes, what am I gonna say at his funeral? I don’t have anything nice to say.” [laughs]

I rushed home. I was set to give a keynote, actually, in Miami, and found out the news and felt something I did not expect to feel. When the news came, I was literally supposed to walk onstage. And I rushed home. Rushed home, and got home on a flight, and I was so disoriented and got the hospital, and he was unconscious. My sisters and I were surrounding him in his bed, and I had this transcendent moment that actually changed my life. I was a different person on the other side of it. And it seemed to me like — here, we didn’t need any more time to hold onto anger. The anger was gone. And it was the anger that had kept me from feeling, really, the things that I needed to feel to move forward and to forgive, all this time. And you know what happens when the thing that fueled you all the time, the anger, leaves. You have to do some dealing.

And we grabbed our hands — at the reluctance of one of my sisters, who just doesn’t like hospitals. And she’s a Leo, and she’s just very stubborn. And she’s like, “Well, y’all go ahead with that.” [laughs] I’m like, “This is your father!” She’s like, “Y’all go ahead.” But we grabbed hands, and I said to him, as he’s unconscious, “Fly.” And “I know you are heavy, and I know the weights you have been carrying are heavy. Let them go, and fly.” And he, soon after, transitioned.

I thought, one, I needed him to do something for me; like I was this little boy, still, in this grown man’s body, waiting for his dad to do some reckoning that he never was emotionally, spiritually mature enough to do. And I was waiting for him to get there.

But what I discovered was that I had come to an emotional, spiritual place where I did not need him to do that for me and was able to release him — not just him, but the anger, the past, the past that chained us together. I would’ve written a different book, and I would’ve characterized him in a different way that did not honor his human complexity, had he been alive before I finished it.

Ms. Tippett: One thing you said, after that story in the book, is, you said that whatever weighed him, the weights he’d been carrying — he could fly — ‘I told him what I had learned to do in his absence.’ But you had that. That’s what you’re saying.

I think I heard you in an interview somewhere else where you were talking about just the complexity of masculinity. And that is really something — that is one of these places where you are very self-searching, this discipline that you talk about that we all have to have, especially those of us who want to be on the side of justice and righteousness, have to constantly be — have to have a critical self-reflection. And there’s a place in the book where you say something like, “With all of my queer magic” that you realized you have privileges of masculinity …

Mr. Moore: Absolutely.

Ms. Tippett: … in terms of how you were treated differently from your sisters, and how mothers are with sons and women are with men. So somebody was asking you — I don’t know what the question was. But here’s what you said — I would like for you to reflect on, as we close — rather than asking the question, what might it mean to be a freer and better man, what might it mean to be a freer human being?

Mr. Moore: Great way to end, particularly because this is what my second book is gonna be about. Plug. [laughs]

[laughter]

But we talk about toxic masculinity right now, and it’s a thing. It’s a hashtag, and it’s something that we employ everywhere we go. And I often remind people to ask what it is that they’re trying to get at by naming toxic masculinity as a thing: so a range, a set, of behaviors, practices, ideas. And then I go, well, are those behaviors toxic, or is it the idea that we create, all of us together, socially, a box, a sort of script that is called “masculinity” or “manhood”? We create these, you do all know that, yes? And I started to think, well, isn’t it the fact that we create these things — as one-size-fits-all frames that people are supposed to figure out how to be big in — toxic? Is not these ideas that we, socially, collectively, somehow force people to follow, socialize people into — are not those things the things that we need to challenge? And so, therefore, I think of gender, in many ways, masculinity, this notion of manhood, as a cage for many people; as a too-small box that does not allow for people to be full human beings.

Ms. Tippett: And we have so many boxes.

Mr. Moore: Right? So, I am interested now — I don’t want to become a better man, because you all know, what I’ve been told manhood is, it’s not anything I’m trying to aspire to. I want to become a better human person. And if we can help people journey to that place, we might find ourselves holding onto the keys that can unlock the cages that are keeping so many of us who have been identified, or identify as men, are socialized into manhood — freedom might be on the other side of that. So I talk about un-becoming — not becoming a man, but what it might mean to un-become: our failing at this project, this cage, these ideas of manhood that have been mapped onto us. I think, to me, that is where our freedom lies.

Ms. Tippett: Thank you, Darnell.

Mr. Moore: Thank you. Thank you so much.

[applause]

[music: “Moon” by Little People]

Ms. Tippett: Darnell Moore is the U.S. Head of Strategy & Programs at Breakthrough, a global human rights organization. He’s also Civic Media Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Innovation Lab. His book is No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black and Free in America.

Staff: The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Nicole Finn, and Colleen Scheck.

Ms. Tippett: Special thanks this week to Kathara Green, Sierra Gonzalez, Matt McDonald, the technical team at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, and all the great people at the Skoll Foundation.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.