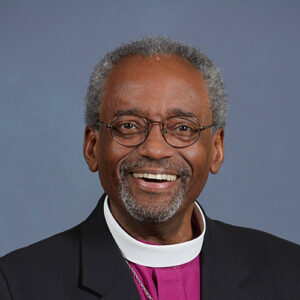

Bishop Michael Curry & Dr. Russell Moore

Spiritual Bridge People

We’re in a tender spiritual moment, widely feeling our need for re-grounding both alone and together. By way of the Almighty force of Zoom, Krista engages a forward-looking conversation with two religious thinkers and spiritual leaders from very different places on the U.S. Christian and cultural spectrum: Episcopal Bishop Michael Curry and Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention. Through their friendship as much as their words, they model what they preach. The Washington National Cathedral and the National Institute for Civil Discourse brought us all together.

© All Rights Reserved.

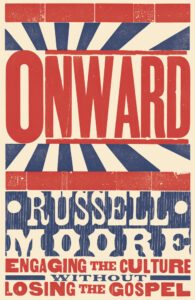

Guests

The Most Rev. Michael Curry is Presiding Bishop and Primate of The Episcopal Church. He is the author of Love is the Way: Holding on to Hope in Troubling Times. He gained a global following after his sermon at the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle.

Dr. Russell Moore is President of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, the moral and public policy agency of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination. He is the author of The Courage to Stand: Facing Your Fear Without Losing Your Soul.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: We’re in a tender spiritual moment as a country — widely feeling our need for re-grounding and healing both alone and together. But calls for social repair and unity are also meeting an understandable wariness. The last years have been bruising all around. So of course I leapt at an invitation to be in a forward-looking conversation with two religious thinkers and spiritual leaders from very different places on our Christian and cultural spectrum: Michael Curry, the Presiding Bishop of The Episcopal Church of the U.S., together with Russell Moore, the president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission – essentially the chief ethicist – of the Southern Baptist Convention. I drew them out to speak in their vocabularies of faith — understanding this as an exercise in public theology. How might convictions about God and the universe, about love and a question like, who is my neighbor — how might these be offerings from the vast human enterprise that is theology in service to our common life at a turning point like this? As much as what these two say — and they differ on much — they model in their presence and their friendship to each other some of the way forward.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Dr. Russell Moore: I think that we have put more weight upon these political, identities than they can bear. We have sort of a vacuum in American life, particularly, of meaning and of connection, what I believe ultimately is answered in the gospel. And so some of these questions have become ultimate in ways that aren’t just about “let’s talk about what we disagree about and how do we go from here,” but who’s stupid and evil and who’s not. And that really just completely cuts off the conversation. Are there stupid people and evil people? Yes, sometimes there’s a combination of the two. But every conversation ultimately becomes that.

The Most Rev. Michael Curry: The Good Samaritan, if you run the risk of translating it, change the characters to today. And I like to say, we might want to retranslate the parable into the parable of the Good Democrat, and it’s a Republican on the side of the road, or the parable of the Good Republican, and it’s a Democrat. You see what I’m getting at? My point is, Jesus is flipping it. Who is neighbor? You see what I mean? Who is neighbor to the one who is hurt and wounded?

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

This conversation was convened by the Washington National Cathedral and the National Institute for Civil Discourse. And it happened over Zoom, as we convene in this Year of our Lord 2020 — with thousands of people watching and submitting questions in advance, which I wove throughout the hour.

Tippett: I want to begin, briefly, by meeting each of you as human beings and getting a sense of the grounding and the history behind your vocation. Bishop Curry, I know that you grew up, as they say, a cradle Episcopalian; your father was an Episcopal priest in Buffalo, New York, although you also had a Baptist side of your family in North Carolina. I wonder if you would describe something that is at the heart of Episcopal and Anglican tradition that has formed you and is forming your presence now, to the life of our country and our world.

Rev. Curry: Ya know, It’s really interesting — one wouldn’t expect that growing up as a Black kid and the Episcopal tradition, the Anglican way, would actually have a crossover, but they do. As a kid growing up, I remember my grandmother and Aunt Lillian, in particular, would often say on different occasions, for different reasons, “Never let any man drag you so low as to hate him.” Now, I didn’t know as a kid that they were actually — and I’m not sure they knew, either — they were actually quoting Booker T. Washington, who said that. But I grew up in a context where people really did believe that the kind of love that Jesus of Nazareth taught is the kind of love that can change personal life and social life. They really did believe that. And it was just ingrained in me.

Well, that’s deeply rooted in the Anglican or Episcopal way of Christianity, that the love of God is the motive for everything God does. I mean, God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son. It’s just all over the place. That’s not unique to Anglicanism or Episcopalians, but it’s deeply rooted in there. And so both my growing up as a Black kid and as an Episcopalian way of being Christian, centered on the way of love as the key to life itself.

Tippett: Dr. Moore, I think it’s right that you are Mississippian, born and bred. Did you also grow up Southern Baptist? Is this the church of your childhood?

Dr. Moore: It is — I grew up in a family that was half Southern Baptist, half Roman Catholic. My grandfather had been the pastor of the Southern Baptist church to which I was born into and belonged all of my life.

Tippett: Well, having grown up an Oklahoma Southern Baptist, I know that what you said was a very big deal. [laughs] That was a divide. That was a chasm, a few decades ago. So I wonder if you would describe something that has formed you, in Southern Baptist tradition, and is forming your presence now to our public life.

Dr. Moore: Well, I would say — and it’s probably of no surprise, as an Evangelical Christian — that that would be the gospel, which is the understanding of good news, that God has presented a way of redemption to the world through Jesus Christ. So it changes the way that I see myself, as a sinner in need of reconciliation that came through the cross and Resurrection, but also how I see other people, which is as those who are created in the image of God and not, ultimately, my opponents. We wrestle not against flesh and blood, the apostle Paul said, but against principalities and powers in the heavenly places. So that view of reality, I think, is what changes and shapes my way of seeing everything.

Tippett: And you said to me, as we corresponded a little bit before today, that your concern for a more civil public square is not in spite of your Evangelicalism, but because of it. And you noted your concern about how vulnerable so many of us, all of us, seem to have become to the false — these are your words — “to the false idea that one’s public denunciation of one’s opponents is indicative of the depth of one’s own convictions, whether to the gospel or to social justice or to family values, or whatever.”

Dr. Moore: I hate the word “civility,” largely, although I will take it; I understand what people mean by it, but I think it’s too low of a bar. I think what the Scripture calls us to is to both conviction, not an evaporating of our differences, but also to kindness and active love for even those people who disagree with us completely. So I think sometimes when we say “civility,” what we mean is pretending as though we don’t have differences, and being polite. And of course, I grew up in a kind of Southern context where one could be brutal with a very strategically worded politeness [laughs] in a way that could word things that could just dismiss the other person. I think we need to have more debate, not less. And so, as someone who really does believe that the scriptures are authoritative, I really do believe that I’m going to stand at the judgment seat of Christ and give an account for my entire life, including the way that I related to people that I may prefer to pretend are invisible at the moment, but are not invisible to God. I think that’s an important thing for all of us to keep in mind.

Tippett: Bishop Curry, something you wrote to me is that, you said, “deep in my soul, I believe that ‘e pluribus unum’ is not simply a quaint Latin saying, but a moral and spiritual imperative for the life the of the human family.” You said, “Learning to live together as brothers, sisters, and siblings means learning to live together with God-given and social diversity, and with real and profound differences.” So very much speaking the same language as Dr. Moore in that sense.

Rev. Curry: Dr. King said, “We will either learn to live together as brothers and sisters, or we will perish together as fools.” And he was right. “E pluribus unum” is the motto, if you will, of the United States. “From many, one” is a vision of this country, and it’s what it could be, but it’s bigger than that. It’s part of God’s vision of the entire human family learning to live together in love and charity, with all of our differences, holding onto our integrities, and yet being able to be in relationship with each other as children of God, made in God’s image and likeness, who have differences and variety.

I’ve been married to my wife 40 years, and good Lord, we don’t agree on a whole lot. Don’t tell her I told you all that, but it’s true. We don’t agree — and she’s always right, of course. But the truth is, learning to live in relationship with difference is called maturity. The human race must move toward maturity, what we call maturity in Christ, as Paul says in Ephesians. And I believe that’s rising up to spiritual maturity that makes, like the old slaves used to say, where there’s plenty good room, plenty good room for all God’s children.

Tippett: I love that. I think it’s interesting, when one speaks of love in the public square, there’s the sense that you’re talking about something soft. But in fact, what we know about how love works in our real lives, it’s the hardest thing of all. And it’s very much about learning to disagree, and staying in relationship.

I think one of the things that came through so clearly, in the comments and questions that came in from this incredible spectrum of humanity that is with us by this miracle of technology — and this won’t surprise you, but I’m gonna name it, because I think we have to name where we are, and we need to keep naming this pain and confusion and fear that is among us, even people who want to move beyond it. I think all of what it boils down to, there’s so much that comes together, to me, in the question of, how can we now proceed with common life or something like healing, in the absence of what feels like any common ground to stand on? So people have said, “We can’t even agree on facts. How can we converse?” “How can I be in relationship with people who have been demeaning to me or threatening to me or what I’m about in the last years?”

Here too, someone said, “We know there’s hard work ahead … But to be honest, I’m unclear how I can help. In my municipality, in my church, most of us voted the same way. How can we discern what is ours to do?” Another person wrote, “Why would I put myself potentially in harm’s way — for example, engaging someone whose views tell them to deny my personhood or that my pain isn’t real?” So I’d really love for you both, pastorally as much as theologically, to respond to the reality of how we’re feeling as a country right now.

Dr. Moore: Which one of us would you like to start, Krista?

Tippett: You start, [laughs] Dr. Moore.

Dr. Moore: Well, I think we actually do have some common ground that often we choose not to see. And some of that has to do with the fact that there’s something in fallen human nature that wants to be self-protective. I think I mentioned to you before we came on today about Eugene Peterson, someone we both admired, talking about an exoskeleton that we tend to put around ourselves. And I think that’s just true of fallen human nature. And one of the ways we can get around that is to try to find a small area of common agreement and then work out from there to our disagreements, and so finding those areas where we do actually see things the same way.

I think of, for instance, the way Jesus is often using parables to go around people’s defenses to get at the heart of what it is he’s saying to them, or the prophet Nathan with King David, who comes in and goes around that self-protective sort of a conscience, in order to talk about a man with a ewe-lamb that’s been taken from him by someone wealthier. I think we can find those places and then move forward as human beings who disagree, including about some really important and significant things, and are willing to have those conversations without suggesting that every point of disagreement is necessarily weaponized.

Tippett: I sometimes wonder if we could even, in the absence of knowing whether we share any answers or any convictions, if we could just gather around some questions we have in common, or gather around the love we have for our children, in common.

Rev. Curry: We got a lot in common. We really do. First of all, we all inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. We have a lot in common. We happen to inhabit the same planet. You cut us, we all bleed. There’s a lot in common. I met a priest out in Utah a couple years ago, who after the 2016 election brought together people in the town where he lives, red and blue, and brought them together, and not to debate issues, although they engaged issues. He invited them, and he had a design for it; invited folk to engage the issue not from trying to convince the other, but tell us the story of your life that brought you to the conclusion that you happen to hold. That shifts. That creates common ground, because everybody, there’s a story. My daddy used to say, don’t judge a book by its cover, read the book, because there’s a story there.

And that story becomes some common ground. A friend of mine said, one of the reasons God told Moses to take off his shoes, in Exodus 3, he said, because God was about to tell Moses his story. And whenever someone reveals the story of their life, that ground on which they’re standing is holy ground. That’s the common ground: we’re human, and we’ve got a story. And if I listen to yours, and you to mine, we won’t agree on a whole lot, but we’ll understand each other. And that produces common ground.

[music: “Appalachian Journey” by Yo-Yo Ma]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with Bishop Michael Curry of The Episcopal church and Dr. Russell Moore from the Southern Baptist Convention.

[music: “Appalachian Journey” by Yo-Yo Ma]

Tippett: Something else I feel has not been named enough, loudly enough, and put out enough for us to grieve and approach, is the way we looked at the maps of our country on election night — some things get colored in red and blue, or there are red states and blue states. But it’s a picture of fracture, and it’s also a picture of interwovenness. These divisions, they don’t just run state to state or county to county, they run community to community, they run neighborhood to neighborhood, sometimes house to house; they run through our families, they run through our lives, and they run through our religious traditions, which are gatherings of human beings and, therefore, microcosms. So each of you has been a bridge person, as your traditions have grappled with divisions and what feel like irreconcilable differences that are also alive in our culture. And I’d love to draw you out a little bit on what that takes, and what you’ve learned, what you can share about what it means to reframe and set these divides on different ground, with the help of religious values.

So Bishop Curry, you have been right in the middle of very vitriolic divisions within the Episcopal church and the Anglican communion, globally, over same-sex marriage. And you have also been in very public conversations that I would say are marked by friendship and respect, with, for example, bishops on the other side of this subject.

Here’s something you said in one of those dialogues: “The inclusion that is at the heart of the gospel, that welcomes gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people, is the same inclusive, outstretched arms of Jesus that welcome those who disagree with us.” Just take us a little bit inside that, what you’ve learned that we can all learn from.

Rev. Curry: Well, it goes back, for me, to the Ten Commandments: “I am the lord thy God. Thou shalt have no other gods but me.” The only god is God. None of the rest of us are, which may come as news in some respect, but it’s a great relief. I’m not God; I don’t have to pretend to be. And therefore, humility is a posture that comes with my humanity.

And one of the things I’ve really — and I struggle with this; it’s not easy to do this — is how do I stand and kneel at the same time, in my relationships with others, especially with those who disagree with me or I disagree with them? Because I’ve got to kneel before them as someone created in the image of God, a child of God just like me, loved of God equally. Love is an equal opportunity employer, and the love of God is equal. So I’ve got to kneel before them, in a sense. And yet, at the same time, I must stand with integrity.

And what I’ve found is, there are times when that is reciprocated. When I was at one of the conferences of the Anglican primates — the archbishops, presiding bishops from around the world — and this was a very difficult one, one of the primates who differed with me profoundly, the two of us got close, in part because he had been a physician in a prior life and I had just recently had brain surgery. And each day, he checked in with me: “Michael, how are you doing?” I said, “I’m doing all right.” And I checked back with him, and we committed to pray for each other. Not the way some folks say, “I’m gonna pray for you” — that’s not a blessing, that doesn’t mean they’re about to bless you — [laughs] but to really pray for you. Now, I know everybody can’t do that. But most people can. There’s more good in most of us, and we can.

Tippett: We’re not all called to be bridge people, but some of us are. Some of us who are safe enough are.

Dr. Moore — so I want to say a little bit about your role, because I think everybody understands, mostly understands, what a bishop is, but you are really the chief ethicist of the Southern Baptist Convention. You’re part of kind of the think tank: you attend to the difficult questions in the public square and inside the faith. And the Southern Baptist church is the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, over 14 million members, almost 50,000 churches, but also — very differently, for example, the Episcopal church, those are all independent churches. [laughs] So to be chief ethicist of that kind of configuration is challenging. And so to say that you’ve been a bridge person in that context, and you really have been a bridge person, especially in recent years, in the Southern Baptist Convention’s grappling with race in its history, in its present.

I want to read something that you said at the 2017 annual convention, which is the only time in the year when the whole Southern Baptist church comes together. You said, “When we stand together as a convention and speak clearly, we are saying that white supremacy and racist ideologies are dangerous because they oppress our brothers and sisters in Christ. They oppress those who are made in the vision of God. They oppress our mission field. Even above and beyond that, unrepentant racism is not just wrong, unrepentant racism sends unrepentant racists to hell.” So the resolution you were arguing for was initially rejected, but it went on to overwhelmingly, nearly unanimously pass.

You have said that in your younger days you were all too eager to fight like the devil to please the Lord. Talk to us — because what you did there is, you made an argument, but it was an argument embedded in the faith.

Dr. Moore: Yes, and I think that’s what’s important, is to have consciences that really are shaped by one’s convictions and then to live those out as best as possible, consistently. And that means if we really do believe that there is a Day of Judgment, then we have to speak honestly about that. If we really do believe that all human beings are created in the image of God, then any suggestion that that’s not true is an assault on the authority of scripture.

That doesn’t mean, though, that we have to, again, evaporate arguments. Bishop Curry and I would disagree very fundamentally on some of these questions that you just mentioned about sexuality; we probably couldn’t serve together — well, we couldn’t serve together in the same congregation or church. That doesn’t mean that we have to see one another as enemies to be evaporated. Rather, we can have what could be very strong disagreements and arguments, but still listen to one another in the public arena. So I think there’s a distinction between — there are certain things that a church, in carrying out its mission, that we have to agree on. We have to be on the same page on certain things, in a way that we don’t expect those on the outside to necessarily understand or to agree with us about.

Tippett: Bishop Curry told this story about coming together with his friend, a bishop on the other side — I hate the way we — it’s so binary, “on the other side of the issue” — that’s also a political form, an “issue” — but through this matter of health. And you have a wonderful story about a friendship with someone who’s part of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, which is actually a group that split away from Southern Baptist Convention, in part around some of these social issues, and that you came together around a shared love of Wendell Berry’s poetry.

Dr. Moore: Yes, a pastor who is completely different than I am, theologically and probably politically, we both were really affected by Wendell Berry and started getting together to have coffee once a month. He used to joke, “We’ll swap back and forth, and we’ll be at the organic coffee place one time, at a Chick-fil-A the next, so that we’re each on our home turf.”

But we would be able to have good conversations that really did get at the hearts of our disagreements, and we would talk through our disagreements. But neither of us had an audience of our own tribe to which we were playing. I genuinely wanted to know, “Why do you think the things that you do? And here’s why I believe the things I believe,” and he did the same. We didn’t convince one another of very many things, if anything, but we came to understand each other as human beings and to build a friendship that way, and one that I greatly valued.

Tippett: How did you discover that shared love of Wendell Berry’s poetry?

Dr. Moore: I think he’s the one who initiated this, because he had seen some things that I’d written on Wendell Berry. And we both had known Mr. Berry and had some connections with him personally, and so that’s how it came together.

Tippett: It’s a great model.

Tippett: After a short break, more with Dr. Russell Moore and Bishop Michael Curry. You can always listen again, and hear the unedited version of every show we do on the On Being podcast feed. You can also watch and share this conversation by video. It’s worth it to see these two very different leaders enjoying each other and modeling what they preach. Find that at The On Being Project, on Youtube.

[music: “Appalachian Journey” by Yo-Yo Ma]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today in a faithful, forward-looking conversation with Bishop Michael Curry and Dr. Russell Moore — leading spiritual thinkers and figures in The Episcopal Church and the Southern Baptist Convention. The Washington National Cathedral and the National Institute for Civil Discourse brought them together, with thousands of people watching via the omnipresent force of Zoom. I wove questions from the very broad audience throughout this hour together.

Tippett: These are three questions — to me, they work together, and I think they speak about what can public theology be for this time. One person says, “As a Christian on the biblical left, I am caught between the desire to bridge the gap with my kin on the Christian right, and the mandate to stand in solidarity with folks on the margins and our more-than-human kin who I see being harmed. Can you give some wisdom on how to live and act in the tension of these mandates?”

A second voice: “I had difficulty registering” — they meant, registering for this event — “because I was asked to characterize my political leanings on a left-to-right scale. I understand why you do this, but it seems to me that one way Christians can contribute to national healing is by encouraging us not to think of our positions in binary terms that have now turned into tribal identities.”

And a third voice: “One of the takeaways from this election, highlighted by some pundits, is that many Americans subscribe to the politics of rage and blame. This is true of many on the left and the right. I seem to recall that many a biblical writer also struggled with the question of who is at fault for my despair. How do we, as humans and as people of faith, present a counternarrative to this notion, while maintaining compassion for the anger and despair?”

I think those are excellent questions that are not to answer, but I would love to know where they land in you and how you would respond to them.

Dr. Moore: Well, I think that we have put more weight upon these tribal, and especially political identities than they can bear. Because we have sort of a vacuum in American life, particularly, of meaning and of connection, what I believe ultimately is answered in the gospel, in a way that something has to take that place. And so some of these questions have become ultimate in ways that aren’t just about “let’s talk about what we disagree about and how do we go from here,” but who’s stupid and evil and who’s not. And that really just completely cuts off the conversation. Are there stupid people and evil people? Yes, sometimes there’s a combination of the two. But every conversation ultimately becomes that.

And I think about the pastors that I know who are exhausted right now in this time of COVID, because every single conversation ends up being, in their communities, some social media war about masks or not masks, or what social distancing ought to look like, because it becomes not just “do we think this is the best way to go?” but “who are we?” Those sorts of conversations, I think, are ultimately exhausting to everyone involved, and I think the end result of it is not a heightened up conviction on either side, it’s cynicism. It’s the belief that ultimately, nothing matters except for screaming into the void. That’s a dangerous place to be as a society, I think.

Rev. Curry: The struggles that I hear behind the questions and the comments are the struggle that we all have: But what kind of person do I want to be? Old preachers used to say, when I was growing up, you look on headstones in graveyards, in cemeteries, and you see the name of the person; then you see the year and date they were born, and then a little dash, and the year and date that they died. And the old preachers used to say, the question is not, when were you born? You didn’t have anything to do with that. When did you die? — you probably didn’t have much to do with that, either. The question is, what did you do with your “dash”? That’s the question.

And when I start there, what did I do with my dash, what is the living legacy I want to leave, what do I want to do with this life — then I’ve got to ask myself the question, who am I gonna follow? What way am I gonna follow and live, to live this life? I believe that the way of Jesus is a challenge. It’s not easy. It is about taking up a cross and following. It is about giving self for the greater good. It is about unselfish, sacrificial love becoming the way of life, just like Jesus, who didn’t sacrifice his life on the cross for anything he could get out of it. He didn’t do it to get famous. He didn’t do it to make money, because he clearly didn’t make any money. He didn’t do it for that. He did it for the good and the well-being and the salvation and the hope and the liberation of others. That’s what love looks like.

I want my dash on my headstone to say, “He may have made a lot of mistakes, but doggone it, he tried to live a life of love.” That’s what. Now, if you want to do that, then that’s gonna be a struggle. That’s not gonna be easy. You don’t believe me, ask St. Paul. Ask Peter. Ask Mary Magdalene. They weren’t the happiest group of fisherfolk who ever came around; when you really think about it — look at the bible carefully, they were the most disgruntled. Peter and Paul went at it. Look at Galatians. They went at it. Paul called Peter out. That’s OK. But they figured out, by following this Jesus, by following his way of love, they actually found a way to live together in ways that they might not have otherwise.

I think that’s true for us. Those who are on the left, who stand for justice and stand for righteousness, I remind my friends, you know what? I agree with you. But justice by itself is not enough. Justice without mercy — read Micah — justice without love can turn into revenge, and that is not the way of God. That is not the social change we want. That is not something that reflects the kingdom, the reign of God, the beloved community that God dreams for us all. So I like that psalm that says, “set me upon a rock that is higher than I.” Call me to something better than Michael’s lowest self. Call me to my highest self, and then help me learn how to rise.

Tippett: Would you offer up that saying from Micah, the prophet Micah, for everyone who doesn’t know it, the teaching?

Curry: “What does the Lord require of you but to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God.” And if we live in God and live in love, we will find ourselves in relationship with God and with each other.

Tippett: I have noticed that both of you, each of you, has used the biblical story of the Samaritan as you have commented on images, teachings, stories to work with, of relevance to how we live together. And I’d just love to hear each of you speak a little bit about that story as something for our life together now.

Dr. Moore: Well, I’m always drawn to what Frederick Buechner said, that we tend to want to go to parables as things that we can just squeeze out like juice from an orange, and toss aside the rind. But what Jesus is doing with the parables is engaging the person at every level, not just here’s the moral of the story, take this and go with it, but here’s how to engage the mind , the imagination, the conscience, the will — and to put people into surprising situations. And I think that’s what Jesus’s parable of what we call the “Good Samaritan” actually is. He takes these assumptions that this lawyer, this teacher of the law, held, and said, you actually don’t believe what it is that you say you believe, by putting him into this uncomfortable situation.

And I think that’s true. This is not just telling us, “you ought to be better people.” It is speaking to us as sinners and saying, “you’re in need of redemption,” and then saying, this is what this looks like, to follow Christ and to see those people who are invisible to you.

Curry: The parables of Jesus really are multifaceted. They can hit you at different times in your life and on your journey, from a different angle. And of late, I’m very aware that the Good Samaritan, if you run the risk of translating it to today, change the characters to today — so who’s the Samaritan, and who’s the person beaten up on the side of the road, and who is, therefore, neighbor to whoever it is, beaten up on the side of the road?

And I like to say, we might want to retranslate the parable into the parable of the Good Democrat, and it’s a Republican on the side of the road, or the parable of the Good Republican, and it’s a Demo-. You see what I’m getting at? The parable of the Black Lives Matter and a police officer on the side of the road, or the parable of a Black Lives Matter person, and the police officer is the Good Samar-. My point is, Jesus is flipping it. Who is neighbor? You see what I mean? Who is neighbor to the one who is hurt and wounded? And he was showing that whatever the lawyer had in mind, when he said — because he asked Jesus, “What do I have to do to inherit eternal life?” — he was asking him, what do I do with my dash? And Jesus said, “The question is, who are you neighbor to, brother?” Who are you neighbor to?

That’s what love of neighbor looks like. And I wonder if Jesus was saying is, life is meant to be lived following his way, as a Samaritan, as a Good Samaritan. And if that begins to happen, imagine what a different society we’d have. Imagine what our political debates would be like. Imagine: we’d have some civil discourse. We’d disagree, but we’d pick each other up when we got to pick each other up, and pour oil on our wounds, and care for each other, and figure out how are we gonna do this together? We got to live together.

Shirley Chisholm said a long time ago, she said, outside of the Indigenous people, the First Nations people of the land, we all came over here on different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now. And we are. And we might as well figure out, how can we live together so that we all thrive? How can we do it? And we can.

Tippett: Dr. Moore, do you want to add anything to that?

Dr. Moore: Well, I think that one of the things that strikes me in the parable of the Good Samaritan is the way that the teacher in the law starts to try to justify himself.

Tippett: Maybe you should just tell the story, because I realize we’re talking about it as though everybody knows the story.

Dr. Moore: There was a really learned teacher of the law, who asked Jesus, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” And Jesus essentially says, “Well, what do you think?” And he said, “You should love God and love neighbor as self. That sums up the commandments.” And Jesus says yes. But wanting to justify himself, he said, “Who is my neighbor?” — what are the asterisks that I can put in here to exempt myself? And Jesus exposes all of this with the story of a man who’s beaten on the side of the road, and one religious leader after the other passes by. But the one who stops is a Samaritan, who would’ve been a despised figure at the time. He’s the one who showed mercy to him. And said, “Who was the neighbor to this man beaten?” Not “who is his neighbor,” but who was he a neighbor to? — this active sense of love — and turned everything on its head.

And I find that that intuition of wanting to say, “How am I exempted from these responsibilities?” is one that at least I grapple with, often. I remember preaching through “blessed are the merciful, for they shall be shown mercy,” and finding myself trying to find some exemptions to that, in terms of people that I wanted to be angry at, at the moment. And I said, what I’m doing here is exactly what I critique in theological liberalism, when I do, which is the idea, “Well, it says resurrection from the dead, but it can’t mean that.” I’m somebody who knows that that’s not the way that it is to be, but I find myself doing the same thing when it comes to what Jesus is commanding me to do. I’m a sinner.

And so one of the things I’ve started doing since then is to say, with every text or scripture that I come across, “If I’m a sinner, then that means that there’s going to be something in me that will try to resist the truth of what God is saying. Where is it?” And if I don’t know of anything, it’s probably not because I’m perfectly holy and sanctified. It’s probably because that’s something that I’ve hidden from myself and really needs to be explored, to say, how do I confront that in myself and turn it over for transformation?

[music: “Careless Morning” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with Dr. Russell Moore from the Southern Baptist Convention and Bishop Michael Curry of The Episcopal Church.

[music: “Careless Morning” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I want to bring, for one last time, a voice from our virtual space. Question was: “What might it look like for the church to become a prophetic witness, address brokenness of our nation and world?” And I think we’ve been delving into that, but this really follows on that: “How do we hold our own traditions accountable for honoring that teaching, and what do each of you look for from the other traditions to help in this work?”

Rev. Curry: Well, I’d go back to Micah. What does the Lord require of you but to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God? There is, in the Christian and the Jewish traditions, a fundamental conviction that God cares about — like the old song said, “His eye is on the sparrow, and I know he watches me” — that God is passionately concerned about the wellbeing of his children and that all that stuff in Matthew 25, in the parable of the last judgment, the sheep and the goats, where God is concerned about “did you feed me when I was hungry? Did you clothe me when I was naked? Did you visit me when I was in prison?” In other words, did you show me justice and mercy and kindness? Did you help me in my humanity when I needed help?

That’s what Judgment Day is about. Jesus is telling a parable about Judgment Day, which I think is a way of talking about what matters to God. What matters to God is, how have we treated each other, because that’s a reflection of what we really think about God: how did we care for each other. How did we care for this world, this creation that we live in? That’s what matters. And so to be concerned about children being separated from their parents at the border of our country, to be concerned about finding ways that we can come together to be a better nation, and finding ways that we will make sure that the poorest among us are cared for, that every child born into this country has an opportunity to become all that God dreams and intends for them, Christians can come to agreement — not just Christians, but people of religious faith can come to some agreement and say: We care about those who often don’t have voices to speak for themselves, and we’ll join hands.

Dr. Moore and I, we have actually done work together, our organizations have done work together around common concerns that were humanitarian concerns, that come out of our faith. We didn’t do it just because we’re social do-gooders. We did it because Jesus — well, you don’t want me to preach. But you know what I’m saying.

Tippett: We do want you to preach, but we don’t have time. [laughs]

Rev. Curry: We don’t have time, no. [laughs]

Tippett: Well, but to the point you just made, something I’m aware of as somebody in media is, so much of the story of our time, and the generative story of our time, is just not told. A light is not shining on it. So to your point — and I don’t think people know how many what would feel like counterintuitive collaborations there are, on matters like immigration and criminal justice reform and ecology, that are happening between the Southern Baptist Convention and Episcopalians and other faiths.

Dr. Moore: Yes, and I think that only can happen when we have groups that will say, “We might not agree on anything else except this. And so we can argue about a thousand other things when we’re on our way to work together on this one thing. But we can agree on that one thing.” And sometimes what we find is that we have more agreement than we thought, sometimes we find that we have more disagreement than we thought, but it’s only by being in that kind of conversation with one another.

I can’t speak for anyone else’s community, I can only speak for mine. And what I hope for is a long-term view of life — and by long-term, I mean trillions of years, which is to say, as a people who really do believe in a heaven and a hell and a resurrection from the dead, to see that life is not just the scarcity of trying to grab onto whatever my career is or whatever my reputation is at the moment. And I think there’s some people who would caricature that as, “Well, if you believe in a life to come, then that means that you just don’t pay attention to what’s going on around you right now.” I find the reverse is true. You’re able to pay attention and to care about the life that you have now because it’s not ultimate, because I can pour myself out and risk myself in love for others and in conviction to the truth, without believing that this is all there is. I think that’s what I pray and hope for, for my own community.

Tippett: We have exactly four minutes left. And what I want to ask you as we finish is how the young inside each of your denominations is questioning and pushing, as the young are want to do — to make good trouble, as John Lewis said.

Are there conversations that they’re driving forward, or priorities that they’ re bringing front and center, that might not have been there before?

Dr. Moore: Yes, but where those conversations are coming is not from a desire — I think some people think of the young as looking for ways to dissent. What I find are, rather than that, young people who are looking for more consistency. The question is not, why do you believe so much? The question is, why are you not living up to what you say you believe? And I think especially when we’ve seen so many high-profile failures, in every institution but also within the church, that’s a very good question. And I know that as someone who went through a spiritual crisis of my own at the age of fifteen — of wondering, is Christianity just another marketing gimmick? and came to the understanding, no, I think this is the way, the truth, and the life — that call for consistency and integrity, that’s what I see coming from our young.

Tippett: Bishop Curry, you get the last word.

Rev. Curry: Oh, my gosh. Well, in a similar vein, maybe from a different set of young people, but some similarities and maybe some of the same, when I saw young people — and it was mostly young people, this summer after the killing of George Floyd, marching peacefully — and they were, marching peacefully — I realized something over time. First of all, it was the most diverse gathering I have ever seen in this — the civil rights movement wasn’t that diverse. And even after Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin and going way back, the marches weren’t that — this was a diverse group of young people.

And more than that, I realized something: what they were protesting was our failure to live up to the ideals and the values that we say constitute what America is really about. They were doing what Thomas Jefferson, if you will, were doing in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” They were protesting that America live up to the values you say you are. Christians, live up to the values you say you hold. Religious folk, live up to the values. They were challenging us. Now, that’s prophetic witness, challenging us to be who we say we are. And I hear young people calling the church and calling religious communities: You say you’re people of God, and you say that God is love. Show me. Like it says in My Fair Lady, don’t talk of love, show me.

[music: “Axiom” by Christian Scott]

Tippett: The Most Rev. Michael Curry is Presiding Bishop and Primate of The Episcopal Church of the United States. He is the author of Love is the Way: Holding on to Hope in Troubling Times. Dr. Russell Moore is president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention. He is the author of The Courage to Stand: Facing Your Fear Without Losing Your Soul.

Special thanks this week to Keith Allred, Cheryl Graeve, Theo Brown, The Very Rev. Randy Hollerith, Michelle Dibblee, Margaret Rawls, Leonard Hamlin, and Alan Yarborough.

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt and Gautam Srikishan.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections