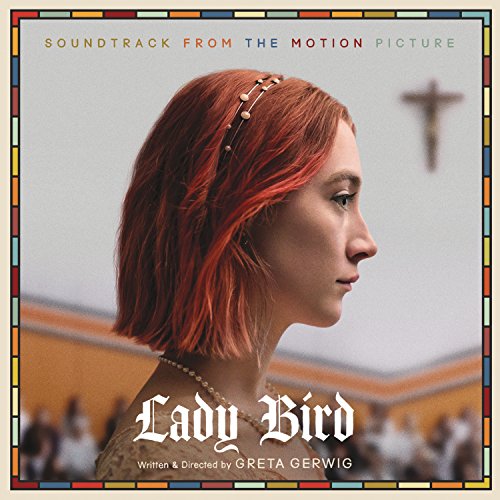

Lady Bird

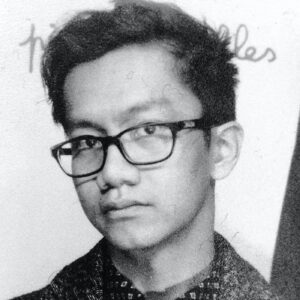

Kyle Turner

As much as it is a coming-of-age story, Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird is also about the complicated relationship between a teenage daughter and her mother. Even as they argue, they want to connect; to be seen and understood as a complex and ever-evolving person by the other. Their on-screen dynamic resonated with writer Kyle Turner, who has had his own challenging relationship with his mother. He says Lady Bird helped him begin to develop compassion for her — and to explore the possibilities of expressing empathy.

Image by Grace J. Kim, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Kyle Turner is a queer freelance writer based in Brooklyn, NY. He is a contributor to Paste Magazine, and his writing has been featured in The Village Voice, GQ, Slate, NPR, and the New York Times.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, fellow movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Kyle Turner about the movie that changed him, Lady Bird. If you haven’t seen it, don’t worry. We’re gonna give you all the details you need to follow along.

[music: “Title Credits” by Jon Brion]

I confess that the first time I saw Lady Bird, I thought it was OK. I didn’t think it was as amazing as everyone who had seen it told me it would be. And that’s largely because of what I brought into it. I was just having a bad day, and, as many of you know, when you’re having a bad day and you go to the movies, sometimes the movie will be changed based on your feelings. But I did the smart thing, and I saw the movie again, and I realized that this wasn’t just your typical angsty coming-of-age story. This was actually about the key moments in our lives that shape our identity. And it was actually a story about a mother and a daughter.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

[music: “Drive Home” by Jon Brion]

The mother and daughter in Lady Bird are Christine and Marion. Christine, who goes by the name Lady Bird, is played by Saoirse Ronan. Lady Bird is a senior in high school, and she just wants to get out of Sacramento and move out to the East Coast, go to any school that is not close by to her family and her parents, who she just feels so misunderstood by. And Marion is played by the amazing Laurie Metcalf, who you’ll know from Roseanne as Jackie, Roseanne’s sister. And the two of them embody that really frustrating relationship that you can have as a teenager with your mother, that sense of wanting so much to connect, and yet not being able to connect.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

One of the most beautiful aspects of Greta Gerwig’s script — and I should say that Greta Gerwig also directed Lady Bird — is how she portrays both sides of this story between mother and daughter. Even though these two fight in very real ways, uncomfortable ways — you’ll want to turn away from the screen because it feels too familiar to those teenage arguments that you had with your parents — she also shows that there’s such care and love between these two women.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

[music: “Thanksgiving in Sacramento” by Jon Brion]

One of the hardest things about growing up is realizing that people are complicated. And our parents in particular can be many things. They’re not just the one thing they are to us, our mother or our father. And that’s one of the other things that I love about Lady Bird, is that the character of Marion, the mother in the movie, isn’t just one thing. Even though at times she can be cruel to Lady Bird, she’s also this loving nurse. She’s also a patient mother who sews her daughter’s dresses. She’s a loving wife. And so seeing that complexity of her just demonstrates how people can be more than one thing.

That idea is something that really resonated with writer Kyle Turner. He writes about movies and LGBTQ culture, and how they’ve helped him shape his understanding of himself and others. Movies were the language that Kyle used growing up to connect to his own mother, and Lady Bird in particular has helped him develop compassion and hope around the complicated relationship that they’ve shared.

So I know that you love movies, because I’ve read a lot of your work. And I especially love, when you were writing in your piece about Lady Bird, the fact that you look to movies for hope. I really resonated with that, and I love the fact that that’s how you approach movies and watching movies.

And under that lens, I’d love for you to think about the first time that you saw Lady Bird. I’d love for you to just, in your chair right now, just close your eyes and think back to that moment when you first saw that movie, and how it made you feel, who you were with; and I’ll come back in and prompt you after ten seconds.

So what memories came up for you right there?

Kyle Turner: I was in a press screening of Lady Bird at New York Film Festival, and I had been anticipating it for a long time. I knew what the plotline was going to be, but sitting in that chair, I was incredibly overwhelmed at the precision of the emotions that Greta Gerwig was able to conjure and how close to the bone it felt, watching a fictional depiction of a relationship that I had a very intimate understanding of.

The relationship between Lady Bird and her mother, Marion, is very, very similar to the relationship that I had with my mother in high school. So many specific conversations felt as if they were taken from arguments that my mother and I had had. And I just kept thinking to myself that it was surreal to experience that kind of storytelling. It felt very confrontational, in a way that was overwhelming because I was with an audience of other people. And I had to modulate the way that I reacted to the film, because I was sobbing through most of it. It was just, I think, the 30-minute mark, and I was just bawling through the whole thing, and I had to stifle my crying, lest I disturb anyone else.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

Percy: You’ve written about that experience watching Lady Bird, for Slashfilm, about what it meant for you and your relationship with your mother. And so much of what you wrote really resonated with me — especially this sentence, because it describes so much how I’ve felt about my relationship with my mother throughout the various stages of our lives. You wrote: “I’ve spent a lot of time hating my mother, as if my life was divided into three periods, the first one being defined by the closeness of our relationship, the second by the tempestuousness and toxicity, and the third, reconciling with what that all meant, trying to recover and heal.”

I’m just curious to know more about those stages of your relationship with your mother and how Lady Bird mirrored that for you.

Turner: My mother and I were very close, when I was younger. I’m adopted, for the record. I was adopted; my parents are white. And much of my early lessons —

Percy: You’re Chinese.

Turner: Yes, and I’m Asian-American; I’m Chinese-American. Much of my adolescence was spent mostly with my mother. She was the one who really started my love of movies. We would go on trips together; we would go to the movies and go to shows together. And my father, as I was getting to the pubescent area, I started hanging out with him more often, around 11, 12, 13. And I think the dichotomy was pretty much a natural evolution, in terms of developing a relationship with the other parent and the normal teen angst and whatnot. But I think it was compounded by reactive attachment disorder, in the sense that experiencing the “trauma” of adoption and whatnot, it shapes the way that I develop intimacy and also the way that I negotiate validation from people.

So when my father died when I was in high school, I was 14. I was a freshman in high school. The teen angst that existed between me and my mother — I was previously able to just escape to my father’s apartment, which was in our basement, because they were separated at the time — that angst boiled over and became this kind of volcanic eruption. So you have this sense of abandonment issue, being adopted, and then you have the teen angst, and then you have the death in the family. And that was too much pressure for both my mother and me to handle.

Percy: No kidding, because you were both individually going through your own lives and your reactions to everything around you.

Turner: And we had very different reactions, in terms of dealing with that bereavement and dealing with that grief. I was much more closed-in, and I was much less inclined to be as outwardly emotional about it, and my mother and my sister, who is their biological daughter, they were a little confused by that, because they were much more explicit about their process of bereavement than I was. They were worried about me and — I don’t think it was a bad thing that they wanted me to go to therapy. But I thought that the way in which they did suggest that I go to therapy was maybe indelicately handled.

But that period of high school, especially, high school and early college, was very, very toxic. We were both mutually abusive to one another and just screaming at each other all the time. That was very, very hard, and I spent a lot of time burying myself into my schoolwork, especially junior, senior year, wanting to get out of Connecticut. I spent a lot of time watching movies. And it was especially during this time where, I think, the idea of finding hope in cinema, in film, in art really crystalized, because of that fractured relationship and that loss.

Percy: One of the things that you’re talking about there that I really appreciate about watching Lady Bird is how it captures — you’ve written about this — the uncertainty and the loneliness that you feel during that time, when you’re — the mess in trying to figure out how to live as yourself and who that is, which you’ve described.

There’s something else that you wrote in your piece about the movie that really just made me remember what it was like to be a teenager and going through that relationship at that stage with my own mother. You wrote, “I’m constantly wondering who I am in the eye of other people. And I assume I am disappointing them or alienating them. I don’t know whether I want to be someone for myself or someone crafted to some degree in respect to others. And I wonder what it would be like, being someone for my mother instead of spending as many years as I have, arrogantly eschewing those expectations. And I wonder what my father would think.”

Tell me a little bit more about that experience in relation to the movie, because what you’re describing there is what I feel like Lady Bird, as played by Saoirse Ronan, what she experiences. It’s this constant push-and-pull between trying to figure out who she is, but then also realizing that who she is may be heartbreaking for her mother. [laughs]

Turner: I think about that. Two scenes: I think about the scene in which she is writing down her name for the audition for the musical.

Percy: Because her given name is Christine.

Turner: Her given name is Christine, and she puts “Lady Bird” in quotes in between, like a middle name, almost. And then the other scene that I think of is towards the end, when she’s trying on prom dresses.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

She’s talking to her mother, and she says, “I just want you to like me.”

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

And her mother says, “I love you.” And Lady Bird asks …

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

… “But do you like me?”

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

And that exchange very much crystallizes, to me, the struggle of trying to become yourself and trying to figure out what exactly that means. What does it mean to become yourself, for the sake of your own self-actualization, I suppose? And what are you either compromising or sacrificing for that? Is that a good thing? Is that a bad thing? How can you exist outside of someone’s gaze? Is that even possible? Does one really want to do that? Are we all, effectively, just a composite of the different gazes under which we exist?

And my thing has been, especially as a queer person, negotiating the gaze of my family, my mother in particular, of course, that of peers who are either queer and white or queer and people of color — trying to figure out where I land in those spaces. And I think a lot of my process of living in New York has been figuring what that means to me. And I’ve usually landed in the space where I’m going to the movies and not hanging out with people.

Percy: [laughs] I think what you’re describing there, with that scene — it was one of the most heartbreaking in the movie, for me, because of the fact that it’s something no one really talks about as a parent. There’s the idea that you love your children — and that in itself can be complicated, because not everyone, probably, does. But then there’s the added layer of liking your children, liking who they themselves distinctly end up being and continue to grow into, and that that’s not always a guarantee. And what do you do if your parents love you, but they don’t like you?

Turner: In another essay that I had written, I spoke about the dynamic that existed between my best friend in high school and his mother. And I was so jealous of that. They seemed to have such a good relationship that they could be petty and argue with one another, but at a normal level. They weren’t screaming.

Percy: Exactly; they weren’t throwing themselves out of a car [laughs] like in Lady Bird.

Turner: They weren’t throwing themselves out of a car. I’m lucky I didn’t do that, although —

Percy: I thought about it a lot. [laughs]

Turner: [laughs] I’m envious of the little cast where she writes, “Eff you, mom.”

But they could argue. And even if his mother would say, “How much are your friends’ mothers spending on” whatever, it would simmer and resolve itself in what I saw as a really normal way, whereas that scene where Lady Bird and her mother are yelling at one another, and her mother is like, “You have cost us so much, and you’re not grateful,” and Lady Bird is like, “Give me a number. Here’s a notepad. Give me a number” — and I had almost the exact same argument with my mother, my sophomore year of college. I was just like, “Give me a number, and I will get very rich, and I will pay you back, and then I don’t want you in my life.”

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

It was part of that dynamic, the desire to exclude her from the most important parts of my life and to throw money at a problem, as it were. And clearly, that is not recommended by any means, but — if that were possible, I would have to be very, very rich to throw money at all of my problems …

Percy: Exactly. [laughs]

Turner: … but that source of anxiety and frustration is a big part of why I didn’t come out to her as queer until much later, in my sophomore year — because we were trapped in a car. I do have a trapped-in-a-car experience, but I didn’t throw myself out of the car.

Percy: What you are describing is what one of the — I re-watched Lady Bird yesterday, getting ready to talk to you. And one of the things that struck me this time watching it is how painful it is, as a viewer, to see the distance between them. And you’re just watching it, and in my head I just kept being, “Just talk to each other. Just say what you’re thinking. Say what you really mean,” and how uncomfortable it was to see just how it escalates. You’d start an argument, and it just gets bigger and bigger and bigger, until you say the thing that you can’t take back that really hurts the other person.

Turner: That’s the thing that you always fear, that if you are given the opportunity, I think, to really express your feelings, you’ll end up saying something that you can’t take back. Even if you don’t mean it, there is a sliver of unconscious truth. And I think what’s fascinating about their relationship and why it was so important to me was that it seemed, for them, that they do love each other, that they are important to one another’s lives, they just don’t know how to communicate to one another. And every time that they try to reach out to the other person, the other person is not ready. Every time Marion reaches out to Lady Bird in some way, Lady Bird isn’t ready to accept that or to communicate or to engage with that. Every time Lady Bird tries to engage with her mother, Marion isn’t ready for that.

And that has been the running narrative of the relationship I have with my mother. Every time that she tries to reach out to me, I’m not ready; I resent her; I think that she’s trying to guilt-trip me. And I don’t think that she’s not trying to guilt-trip me, but I could just suck it up. Every time I try to reach out to her, she’s caustic and brings up something and escalates a situation, etc., etc.

And I think that very basic skeletal structure of those relationships are really what feels so sharp about Lady Bird as a film, as a piece of writing, and why it’s so important to me, because I understand so crucially the fear of really communicating at one another’s level and still having something being misunderstood, and having something escalated till you reach a point of no return.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

Percy: I love that you point out that they’re not ready, at different stages in their relationship, because that is so true to life. And in fact we see in the movie, Marion, Lady Bird’s mother, writes her these letters — she crumples them. When Lady Bird decides to go to college in New York City, her mother’s trying to talk to her. She’s ignoring her in real life; she’s not talking to her in real life. [laughs] And she tries to write these letters to her and then ultimately decides that she doesn’t want to. Her father, Lady Bird’s father is the one who rescues these letters from the trash and then packs them in Lady Bird’s suitcase so that she can read them when she gets to New York.

But even then, I think about how it was on her mother’s own time. It wasn’t actually in relationship with her; it was her isolated, alone, writing this to her. And then the movie ends with Lady Bird leaving this voicemail on her parents’ answering machine. They don’t answer; she leaves this voicemail. And she says to her dad, “Dad, this is more for Mom.” [laughs] And then she proceeds to tell her, ultimately, “I’m Christine again,” and doesn’t really say much except to say that “I see you, Mom. I see you.”

Turner: I kind of hope that the essays that I’ve written about our relationship are sort of my versions of Marion’s letters. And I’ve only just thought of that now, honestly. I have thought about the essays in relation to one another, but in a vacuum; not necessarily analogous to that. But I think now I hope that they might be crumpled letters that my mother at some point finds.

Percy: One of the things that comes through in your writing about Lady Bird, and even as you’ve been here talking with me, is how much you clearly have compassion for your mother. And you see very much how she wants to communicate with you and how she struggles. I’m curious when that happened for you. Did it have anything to do with watching Lady Bird? Because the way you write about it, the compassion really comes through.

Turner: Thank you. I really appreciate that. I do think that Lady Bird had a very big role. I will say that the initial reaction, coming out of Lady Bird — I texted my mother “I love you,” we began communicating more amicably for the next year or so, and then something happened to readjust the relationship again. But I do think that Lady Bird was really fundamental in trying to develop a way to have compassion for my mother; to better understand that, as much as film could be a shared language between us, it wasn’t going to be the be-all, end-all solution to some deeper problems that we both have to be held accountable to and for.

Also, it was definitely a process. It’s been a process to better understand how to approach the relationship, even at the current state that it is in, even the distance with which it is currently being negotiated, or not. Being an adult — Lady Bird was released in 2017, I believe. And even in those two years I think it’s been much healthier to not see the relationship and not completely lens it through cinema as romantic. I think that, hypothetically, that might be more of a hindrance than a help. It’s a good starting point, I think, to go from there and to better negotiate our issues, but I recognize that just thinking, “Our love for this movie that depicts our relationship is gonna fix everything” — that’s not true. It requires work on both people’s ends, and I think just living in New York and dealing with other personal relationships and professional relationships has taught me how to be mature about them. And I think that sort of critical perspective can also be applied to much more intimate, much more problematic or tempestuous or complicated relationships as well.

Percy: I think you’re so right. I have this conversation often with my friends who are very close to their parents. And then I feel very lucky to have a complicated relationship with mine, because it’s prepared me for a lifetime of complicated relationships [laughs] in a way that they seem constantly surprised by. [laughs] I do feel like it was a gift.

Turner: I think it’s — even though we have had such a tumultuous relationship, I don’t think I would change things, because then I wouldn’t be the person that I am today. I do mourn the possibilities of what it would be like to have a more stable relationship with my mother, but I also think that it has been very important to my development as a person and as an independent person. And it would be curious to see what my life would be like to either balance those two things — to have a stable relationship but also be some iteration of who I am today, if not exactly the same — or to just have that stable relationship and see what my life would be like in the aftermath of that, I suppose.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

Percy: This actually reminds me of something that I wanted to point out that’s so beautiful about the script that Greta Gerwig wrote, and I’m wondering if it stood out to you, as well, which is the fact that Marion, her mother — so she has this complicated relationship with Lady Bird. She has a lot of stresses. But there’s also so much love and intimacy that’s shown between her and her husband — between her and Lady Bird’s father — and also in her job. She is clearly loved at her job. We see that. And she’s so great at her job. She works in a psych ward — is that the best way to describe it, probably? — with people who are going through terrible, terrible times in their life — distress; depression. And I just love that that detail was included, that she can have this difficult relationship with her daughter, and yet look at how she helps other people.

Turner: One of the first scenes that we see her at her job, she buys a little present for a coworker’s child. She clearly has empathy for other people. And I think the paradox that we find with people that we have intimate relationships with and complicated relationships with is that they’re able to show such great empathy for other people, but we don’t understand why they can’t understand who we are or what our issues are or what our relationship is.

Percy: Or show us that empathy.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

This is another thing that I think was so brilliant that Greta Gerwig did was, we see her sewing Lady Bird’s dresses; we see the care she takes for her. It could’ve been very easy to create this angsty teenage movie, coming-of-age movie, where the mother isn’t represented in a full way. And she chose not to do that.

Turner: There are single lines in this film that are spoken by different characters, where you just imagine their entire life; that we just seem to come upon them and find them at the right moment, and yet we have the best and fullest impression of who they are. And one of those lines, to me, is when Marion is scolding Lady Bird for coming home late after a date. And Lady Bird is saying, “Don’t you wish that your mother didn’t yell at you?”

Percy: Oh, because she didn’t put her clothes away. Yes, they’re all over her room.

Turner: And Marion just shoots back, “My mother was an abusive alcoholic.” And that was also the situation with my mother. And now, again, being an adult, I have a slightly better understanding of where my mother was coming from and how that trauma must’ve shaped her relationships and her life, including the one that she has with me. I don’t think it’s necessarily an excuse, but I think having that empathy for that background still can be language or a key to understand or to approach the relationship, moving forward.

Even when we had an argument last Christmas — not the most recent Christmas, but Christmas 2018, I think — and even then, I think we handled it much better than I would have when I was in high school or when I was in early college. It was just sort of an accepted “I’m a little frustrated with you; I think we should back off a little bit.” And I think, in the time since, we’ve started talking more, a little bit more.

I think Lady Bird has been a really important text in that way, in terms of knowing how to modulate and to explore the possibilities of expressing empathy, and being more aware of how you communicate with someone with whom you have this complicated, intimate relationship.

Did any of that make sense? My apologies.

Percy: No, it made complete sense to me. I was just thinking to myself, “That’s progress.” [laughs] That’s what progress looks like.

[excerpt: Lady Bird]

[music: “Always See Your Face” by Love]

Kyle Turner is a queer freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York. He is a contributor to Paste Magazine, and his writing has been featured in The Village Voice, GQ, Slate, NPR, and The New York Times. His beautiful and moving essay on Lady Bird was published by Slashfilm and is called “How Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird Saved My Relationship With My Mother.”

IAC Films, Scott Rudin Productions, and Entertainment 360 produced Lady Bird, and the clips you heard in this episode are credited entirely to them. Jon Brion scored Lady Bird, and Lakeshore Records released its original motion picture soundtrack. Legacy Recordings released an album of all the non-scored songs from Lady Bird. And shout out to Marta, my sister-in-law, who still believes “Crash Into Me” by the Dave Matthews Band is a classic.

Next time on This Movie Changed Me, I’ll be talking with poet Danez Smith about The Color Purple. The movie was adapted from Alice Walker’s singular book and stars the equally singular Whoopi Goldberg and Oprah. You’ve got a week to watch it before our next conversation, and just so you know, you’ll probably fall in love with Whoopi Goldberg. I know I do, every time that I watch it.

The team behind This Movie Changed Me is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Eddie Gonzalez , Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Tony Liu, and Kristin Lin. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota Land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and Poetry Unbound. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

I’m Lily Percy, and it’s OK if the people you love don’t always understand you. You know who you are.