Tracy K. Smith and Michael Kleber-Diggs

‘History is upon us... its hand against our back.’

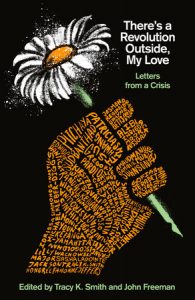

The pandemic memoirs began almost immediately, and now comes another kind of offering — a searching look at the meaning of the racial catharsis to which the pandemic in some sense gave birth and voice and life. Tracy K. Smith co-edited the stunning book, There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis, a collection of 40 pieces that span an array of BIPOC voices from Edwidge Danticat to Reginald Dwayne Betts, from Layli Long Soldier to Ross Gay to Julia Alvarez. Tracy and Michael Kleber-Diggs, who also contributed an essay, join Krista for a conversation that is quiet and fierce and wise. They reflect inward and outward, backwards and forwards, from inside the Black experience of this pivotal time to be alive.

Image by Laylie Frazier, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

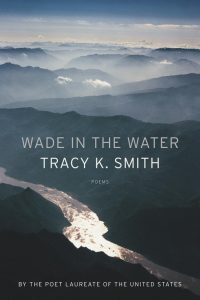

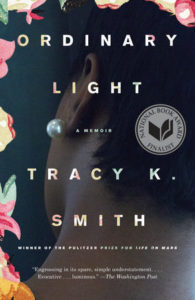

Tracy K. Smith is a professor of creative writing at Princeton University and the former Poet Laureate of the United States. Her poetry collections include Life on Mars, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Duende, and Wade in the Water. Her memoir is Ordinary Light. She’s the co-editor of the book, There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis.

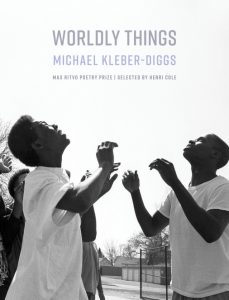

Michael Kleber-Diggs is a poet, essayist, literary critic, and arts educator. His debut poetry collection, Worldly Things (Milkweed Editions 2021), won the Max Ritvo Poetry Prize, the 2022 Hefner Heitz Kansas Book Award in Poetry, the 2022 Balcones Poetry Prize, and was a finalist for the 2022 Minnesota Book Award. Since 2016, Michael has been an instructor with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. He also teaches Creative Writing in Augsburg University’s low-res MFA program and at Saint Paul Conservatory for Performing Artists.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: The pandemic memoirs began almost immediately, but now comes another kind of offering — a searching look at the meaning and possibilities in the racial catharsis to which the pandemic in some sense gave birth and voice and life. Tracy K. Smith co-edited the book There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters From a Crisis. She joins me together with Michael Kleber-Diggs, who contributed to that work. It is a reflection inward and outward, backwards and forwards, primarily of the Black experience of 2020 and all that the murder of George Floyd came to mean. But the 40 voices in this volume span an array of BIPOC lives and perspectives, from Edwidge Danticat to Reginald Dwayne Betts, from Layli Long Soldier to Ross Gay to Julia Alvarez. This conversation with and between Michael and Tracy is soft and fierce and wise, and it’s a privilege to be part of, along with the gift of their writing.

[“Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Michael Kleber-Diggs: “It wasn’t that I wanted to let go and sink. It was that it was hard to keep my head above water and carry my stone at the same time. I wanted a place to rest. Okay? I wanted to float, just for a little while.”

Tracy K. Smith: “Dear Black America — We are many things, aren’t we? We are hair. God yes, we are hair. And song. And memory. We are a language so deep it has no need for words. And we are words that feint, dart, and wheel like birds. Like James Brown, we feel good. Like Fannie Lou Hamer, we are sick and tired. We are fearsome. We are fire. Like God, we are that we are.”

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Michael Kleber-Diggs teaches creative writing through the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop and at colleges and high schools in Minnesota. He lives, as do I, in St. Paul, and is just publishing his first book of poetry. Tracy K. Smith is a professor of creative writing at Princeton University, author of wonderful books, a former Poet Laureate of the United States, and a former guest on this show.

So Tracy, let’s just start. You co-edited this book, and I’d love to start with this — maybe these are your first lines, but certainly, early in the introduction that you wrote — that you entered the summer of 2020 with this feeling of having come to a crossroads. And you said, with that came “the sensation of being pulled simultaneously forward and backward in time.” So talk a little bit about that.

Smith: I mean, this year amplified a feeling that I have had for some time, that history is upon us, history is not only on our heels, but maybe it’s catching up and we’re feeling it, its hand against our back. And during the pandemic, witnessing so many acts of violence against unarmed Black citizens, which is nothing new, but almost feeling as if all of America was held in place in a theater, watching this happen and reacting together, amplified all of the feelings of grief, anger, and determination to muster some sense of an adequate response and a sense of, OK, how do we move forward with a different momentum, something other than this rote historic pattern playing itself again and again?

I had — like everyone, I had months to sit and turn that question over in my mind, both in language and in terms of the inevitable emotions that were, you know, also upon me, and to learn something new from my own vocabulary, for language, but also for feeling. And I just had this desire to do that together with everyone else in America and see if we might, you know, get somewhere.

Tippett: So Michael, you are in Minneapolis. One of the things you wrote, you say, “Being born Black in an anti-Black country is like being handed a stone at birth, an object you have to carry and can never throw,” and that one of the effects of George Floyd’s murder, at least in the beginning — you had a sense that people saw that, partially; that you felt seen, not fully seen, but differently seen.

Kleber-Diggs: Yeah, seen in a different way. And I was — at the time that I was writing that, I was thinking a lot about, how do I capture this moment? I was thinking about myself and this place, the Twin Cities, which is my home and an area that I love in so many ways — but thinking about myself in the space and feeling hyper-visible at times and invisible at other times, but definitely, during that summer, during last summer, feeling hyper-visible, feeling noticed, and also spending some time reflecting on how I was being noticed and what people wanted to communicate to me in their interactions — often without words, but just, you know, the smiles, the — I described them, I think, as “overeager” smiles. And I was thinking about that and how that, over time, could start to dissipate as we get back to regular routines.

Tippett: Something you wrote, you said, “Fifteen days after George Floyd’s death, a familiar hopelessness set in… As I walked Ziggy and Jasper around the neighborhood, many passersby viewed us with concern. The overeager smiles of late May and early June—smiles communicating concern for my well-being, smiles that said you are welcome here—succumbed to a familiar consternation, suspicious eyes, some friendliness, but also long wary looks from people I’ve lived among more than ten years now. My steps grew leaden and sad. You see, I am carrying this stone.” There’s that stone again.

And then you turned to a song called “Chocolate” and started dancing in the streets, regardless of all of that. [laughs]

Kleber-Diggs: Right.

Tippett: Would you read — do you have your book with you?

Kleber-Diggs: I do.

Tippett: OK, page 44 — starting at that paragraph on page 44, “More than anything,” and then to the end of the chapter.

Kleber-Diggs: Sure.

“More than anything, one line in ‘Chocolate’ stood out for me. It’s a line connected to a life preserver that arrived when I felt I couldn’t tread water much longer, when I was tired and felt alone, like there was no safe harbor in sight. It wasn’t that I wanted to let go and sink. It was that it was hard to keep my head above water and carry my stone at the same time. I wanted a place to rest. Okay? I wanted to float, just for a little while. There’s the line that says this song is just for you, Michael. All my songs are for you and for us—people born into it and people who opt in. The line always arrived right on time. Whenever Big Boi said:

Making music for the people that be feeling me…

my pulse rate elevated. My heart beat hard—vibrant and alive. We are vibrant and alive. See? He said:

Making music for the people that be feeling me…

and I had the same thought every time: ‘Chocolate’ is a club song, and I am in the club.

‘Chocolate’ is pro-joy, even though our club is bittersweet. We dance anyway.

‘We deserve pleasure.’ I say it out loud.

I can bring the club with me wherever I go. We can spark a revolution just by walking down the street.

The club is a place where I belong.

I’m never alone, I realized. The club is with me wherever I go.”

Tippett: Just say a little bit about the song, just bring others into that experience.

Kleber-Diggs: Yeah — so first, I’m prone to obsessions. The app I use to listen to music gave me the data at the end of the year, and “Chocolate” was my most listened-to song, and I listened to it something like 86 times. So that’s so within my character — [laughs] like I’m like, “Oh, I’m really crazy about this thing, and I’m just not going to stop listening to it, forever.”

And I realized at a certain point that I was really relying on it. I just was sad and angry and frustrated and disappointed and deeply concerned. The pandemic had its own weight. I think we had entered the pandemic with a measure of fatigue from, shall we say, a difficult presidential term. And my daughter was home from college, and she was dealing with the stress of the pandemic, and a lot was going on, and it was just heavy. And I had these two dogs who needed to go out all the time. And every time we went out, I would put the song on. Whenever I listened to it, I just felt reminded that we’re going to be OK. I would feel a lightness that I just needed to have.

And it’s so joyful, and silly in ways, but it’s also got these phrases that seem amenable to other interpretations. And so I just kept kind of connecting to, like, what’s going on here? What’s really at work? Is this just a club song, and I’m overdoing it — which would be completely in character, as well — or is there more to it than that? And I just started to think, with art — that with art made by Black artists, there’s always, I think, a subtext. There’s always a context. And within that, I just couldn’t help myself, though, feeling light and wanting to dance and kind of, in a way, giving myself permission to do that even though — you know, I don’t feel totally comfortable dancing in my neighborhood.

Tippett: [laughs] It’s Minnesota, after all.

Kleber-Diggs: [laughs] That’s right. Like, how can I — and also, how can I call more attention to myself? But I just didn’t, also, feel right not dancing.

[music: “Chocolate” by Big Boi]

The song is just so compelling in that way, and I needed to dance and to feel light and to be joyful and to be conspicuously joyful. And I understood that anyone who saw that might think it was unusual or misunderstand it, and then I realized, it’s not for them, though. It’s not for them. It’s for me. And there was something important, I think, about also giving myself permission to be myself, wherever I am.

Smith: That makes so much sense to me, Michael, and it’s so amazing. I’ve loved that essay, but it’s so beautiful to hear those lines in your voice. And one of the things that you do that I think great poems do, great literature does, is to alert us to spaces and distances that we may not have been aware of. And so you bring in that really powerful and painful image of the stone. And then you talk about other, white — the white awareness that this is your burden.

But there’s also — the sense of joy that you bring in alerts us, and potentially anyone watching, to the reality that the burden is not — it’s not Blackness.

Kleber-Diggs: No.

Smith: It’s the gaze that’s directed toward Blackness. There’s a distance between the stone and the you.

Kleber-Diggs: Right.

Smith: And so the fact that the joy and the song allow you to make that space feel large, even just for the length of a dog walk or for the length of those beautiful sentences — that is like, you create the sense of joy in my body, as I get to that moment in the essay.

And I also have felt so powerfully a version of what you describe as needing to be my full Black self, in plain sight. And I think it’s a direct result of the immense pressure and the willful blindness that has sort of surrounded us, as Black people, for so long, and wanting to push back against that, wanting to make the space not only larger, but also felt on the other side. And I feel like that’s a really productive — I want to tell myself, the club that you’re talking about is an old, old club, and it’s a productive union.

Kleber-Diggs: Yeah. I mean, I think that’s exactly it. And I — Tracy, I don’t know if this is true of your experience as well, but I was raised at a time when a common guidance for Black children was: conduct yourself in a particular way, dress a particular way, act a particular way, and you’ll be received in a particular way. If you dress and speak and act in a “proper” way, people will see your humanity.

And I think that that message, at the time, was part of an effort to have — I mean, this was shared with me by people who loved me and wanted the best for me, and wanted for me a life free of adversity and racism and suffering. And I think we know, now, that that’s — that there’s more to it than that. [laughs] And we are a complex and dynamic people — there is no monolithic Black experience. And we are many things, and we have many interests and disagreements and all of those types of things. And I do think I find myself, sometimes — “performing” feels a bit brisk, but it also feels terribly honest — kind of performing within that tradition that I grew up in. And breaking free of that, and just acting the way I want to act, in a particular moment, connected me to my humanity in a more expansive way.

Smith: Yeah. I totally understand that feeling, and I know that the assimilationist values — [laughs] that’s what I would call them — that my parents, who were born in the ’30s, brought to my upbringing have run their course, as I see it. I feel that the genius, resilience, and the vantage point of the stone, as you call it, and the double consciousness that DuBois calls it — I feel like those are really related concepts — these things hold the solution to America’s current crisis. These things can no longer be kind of like, relegated to the margins, if America wants to survive and evolve. And so I almost feel called to bring, from that other large space and that other set of capacities — I feel called to bring that out into dialogue, into presence, as a tool, almost.

Kleber-Diggs: Right.

[music: “BUS RIDE” by Kaytranada]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with Tracy K. Smith and Michael Kleber-Diggs, contributors to the new book There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis.

[music: “BUS RIDE” by Kaytranada]

And Tracy, I really feel like that’s something that your — I mean, it’s — “A Letter to Black America” is your chapter in the book. It’s interesting for me to hear you say that about the calling, because this is an expression of that, as you describe it. When I interviewed you before, when we sat together in New York City, you were the U.S. Poet Laureate. I mean, you were representing the United States of America, right? You were representing to all America. And this essay is your voice that I recognize, and there’s an intimacy here; there’s a tenderness and a fierceness that is you opening something else up. I wondered if you would read this in two parts.

Smith: Sure.

Tippett: And let’s talk about what you’re saying, and then we’ll also do the second half.

Smith: OK.

“Dear Black America—

We are many things, aren’t we? We are hair. God yes, we are hair. And song. And memory. We are a language so deep it has no need for words. And we are words that feint, dart, and wheel like birds. Like James Brown, we feel good. Like Fannie Lou Hamer, we are sick and tired. We are fearsome. We are fire. Like God, we are that we are.

I’ve always felt great freedom in the countless territories making up the realm of Blackness. So many routes to wholeness. So many versions of joy. In Blackness I am local. In Blackness I am also distant kin. Indigenous and immigrant at once. Host and welcome guest.

But in the country of America—the physical and psychic territory in which the physical and psychic domain of Black America is situated—we are made to huddle together. By force. By the feelings of rage, threat, exhaustion, disappointment, and long-suffering that swarm us in this nation that loathes, fears, regrets, and cannot yet fully bear to accept the fact of us.

And I hear my uncles saying, ‘Tell me something I don’t know,’ with laughter in their throats. And it is that laughter—our laughter—that I cleave to.

We revel in the depth and the flair and the belief and the secrecy of Blackness. We are lucky to be who we are, and we know it. And I hear my aunts saying, ‘Amen,’ and their deep intaking of breath, followed by a steep exhalation.

Black, we revel in the resourcefulness and the resilience and the poise and the know-how and the grace and the anger and the prayers to all manner of beings that have kept us alive. Alive despite attempt after concerted attempt to annihilate us.”

Tippett: Have you ever written all of that down before, for a general audience? [laughs]

Smith: [laughs] No.

Tippett: Am I right that this is a product of 2020 and this “after”?

Smith: It is. I mean, I’ve felt this thinking rising in my consciousness. And sometimes I have prefaced a poem — a Civil War poem that I read many times during the laureateship — by saying something about the resilience that has prevailed despite all of these attempts at annihilation. But this is different. And what this is is — I hope it’s two things. It’s me talking to us, me and the club, and saying, “We are so here. We are so prepared to keep doing this thing that we must do. Thank you. Thank us, and let’s keep going.”

But it’s also, and I hope, an address that excludes a white reader but invites the white reader to observe and listen and eavesdrop and reflect. And I feel that this is what — this is the angle that so much of my current poetry has kind of adopted, not necessarily strategically, but because this is where my head is. This is where my heart is right now. As a Black person in America — as anyone who’s not white, in America — you know what it feels like to be the unintended audience of something and to have to bend your ears in a certain way to accept and deal properly with a statement that isn’t intended for you but that implicates you in some way. This is a skill. And this is a skill that it’s time for those in the community of whiteness to embrace, because, like I said, I think the salvation of our culture — and I don’t really think that’s an exaggerated term — depends on that kind of expanded awareness of self, of place, of where we are and what we’re doing here together.

Tippett: And who we are, right — that larger we that we must also make real, in a completely new way that includes all of us.

But is that OK? Is that all right?

Smith: I think that’s OK. But what it also means is, if “we” is all of us, it’s not what you’ve thought it was, all this time.

Tippett: Yeah. Yeah. We have to remake that “who we are,” what that means, in every way.

Smith: I think that’s exciting work. But I know it’s also threatening to many people, in different — for different reasons, because it’s work that’s saying, power needs to be rethought, and we can get somewhere we haven’t yet been, which is also exciting, but I can understand how that might be frightening. But we know where we have been, and none of us is willing to go back there. No one who understands the full extent of the violence, pain, suppression, etc., that the past has been characterized by is going to willingly go back there. And so the we needs to kind of shift gears.

Kleber-Diggs: I’m thinking also about how we can’t talk about our resourcefulness and resilience without acknowledging how we acquired it. And when I think about “we” in the most collective way, and the community that so many of us are working toward and some of us are afraid of, that history just feels so vital to getting to where we want to be — to acknowledging that, to seeing it, to understanding how it affects us in the present, both in terms of our structures and institutions, but also in our bodies, in — not to overplay it, but in what we’re asked to carry, what our parents were asked to carry, and their parents, and how that arrives with us to where we are right now.

Smith: It’s funny, you know, when we think about it as what all of these generations that have made us possible have been carrying, it goes from being a burden to being a birthright, right? It goes from being this extra labor to being this, I don’t know, like a toolkit, a psychic and spiritual and actual toolkit. And it’s that, you know, like the spectrum of the metaphor that is really interesting to me. America has been very eager to just look at the two ends of the spectrum and not to dwell on the nuance, the subtlety, the transformation, the evolution that sits between burden and freedom.

But there’s something so liberating about actually being open and vulnerable to the painful, real reality of burden in all of its stages, and what happens. Where is the moment where a shift occurs and freedom begins to be born? Like, these are the instructive lessons that are really hard, but they seem essential to getting from ’21 — 2021 to whatever future sits beyond that.

[music: “Hesitation Theme and Variation Blues” by Marisa Anderson]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Tracy K. Smith and Michael Kleber-Diggs.

[music: “Hesitation Theme and Variation Blues” by Marisa Anderson]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with Tracy K. Smith and Michael Kleber-Diggs. They have contributed to a stunning book of 40 BIPOC voices looking inward and outward, backwards and forwards, from inside the racial catharsis at this pivotal time to be alive. [Editor’s note: The collection features 40 contributors — many of whom are BIPOC, but not all.]

You know, I think about the language of revolution, right — and the title of this collection is, There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love — because, you know, Tracy, to that point of how revolutions actually happen, I think there’s a simplistic imagination that it’s this one big uprising. But in fact, revolutions are messy, and they go forwards and they go backwards, and it’s not like everybody’s ever ready for a revolution, or the path has been laid and everybody sees it. It’s when the lid is still on, but it’s slipped.

And I think that’s one way for us to start reflecting, and what you’ve done in this book is start reflecting on the not being able to go back, even though we don’t know what going forward means, necessarily. And all of these things, all these words that you all have mentioned — genius and resilience and tiredness and burden and joy — it’s all there, but even with that tiredness and exhaustion, there’s no going back. There’s no standing still.

Smith: Yeah. I mean, one of the beautiful things about listening to so many different voices in what are, in some ways, hot takes from this year, from last year, is you get to notice the moments, or you get access to the moments when each individual feels something bubbling up that bubbles into clarity and that can be just held because it’s been brought into language.

Tippett: Would you read, now, the second half of your essay, “A Letter to Black America” — so starting with “I see you in all your forms”?

Smith: Sure.

“I see you in all your forms, Black America, and I feel inside me a welling up of pride, reverence, and fierce protection. These threats we live subject to—these ceaseless, baseless, unending and uneradicated threats to our Black bodies, spirits and minds—do you know what I think they are? They are the grotesque and perverse ends to which a nation founded in shame has gone in order to avoid atoning for its crimes. They are defensive acts, based on the belief that if we were allowed to dwell in our full power, what we would bestow upon this nation would be vengeance.

But we know better, don’t we? Look what we do with our voices. Look what we build with our hands. Look what we hold together with just our arms.

Once a friend told me, ‘I think we came to this earth to save it.’

Once, I wrote in a notebook, ‘Maybe we are operating at a heightened spiritual frequency.’

Why else do we call it Soul?

Black America, I feel myself cradled by this thing we share. When I call it race, I’m told that race is false. When I call it a movement, I’m reminded that we have moved through countless other movements before now. When I call it culture, I feel the seams of the word splitting at the great moving heft it attempts to contain.

We are here in America now as we have been in America always. When we are struck down and held back. When our bodies are corrupted by the violence of others. When we love. When, as now, we are trapped inside of finitude and flesh. During all of this and then some, Black America, we are agents of the eternal.”

One of the things that’s been helpful to me, through the challenges, the debilitating angst and depression, but also the consternation of the past year, has been trying to shift scales, mentally. So if I’m dealing with vexation in one context, I try and see if I can go above that and look at it from another point of view. And that’s a habit that I think I’ve tried to make useful in real life because it’s something that you can do in a poem: you can move from the grounded and the local to the cosmic, instantly, and you can glean a new kind of insight or even power from that shift. And so I feel like that’s a part of the work that that piece of writing seeks to arrive at, in a way — say that we are doing many, many, many, many more things than we might at any one given time remember that we’re doing.

Tippett: Michael, I wonder what you’re thinking.

Kleber-Diggs: Thinking a lot about multitasking and how it’s simultaneously ancestral and cosmic and rooted in something that’s very deep and very connected to the Earth and to our spiritual selves, and also very present in the now — in this moment in time and in this context, and how we’ll need all of those gifts as we do the work that we’re going to do.

I was also thinking about imagination and how we can’t, I think, arrive at the future we claim to want — and honestly, that many of us do want — that we can’t arrive at the future we want unless we imagine what that’s like, and how important it is to dream and to be bold in that dreaming, not to contain it with policy specifics or practicalities, but just to really envision the future we want and then manifest that — see the possibilities as limitless and orient ourselves toward liberation and a world where everyone’s humanity is recognized, without qualification or prerequisite.

Smith: In some ways that’s also a part of the story of this quarantine, because there are — for some people, there have been regions of this, now more than a year, where the pressures that force us to do certain things, in terms of work or obligation, some of those have eased up. And so there’s this quiet space where choice comes in, and we get to say, oh, what do I care about? Who do I care about? How do I like to be, when nobody is demanding that I’m other than that, that version of myself? And so some of us are kind of finding little glimmers of what that might look like, what that living by choice, cherishing certain things that don’t always have a hold on our attention — we’re getting a little bit of practice at that. And that also feels really relevant to the larger goals that we’re also talking about.

[music: “Kat’s Gut” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with Tracy K. Smith and Michael Kleber-Diggs, contributors to the new book There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis.

[music: “Kat’s Gut” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

Tracy, I think you pointed at this a minute ago, and also I think both of you work with young people, and — but it’s so — it is a shift in perspective, not to diminish what is terrible, and also what’s been terrible about what we’ve all gone through and how many varieties of that experience there are. And there’s something extraordinary, which I think maybe only now, as we end — not everybody in the world, but we in this country start emerging from the pandemic — to be the generation of humans — I don’t mean demographic, I mean this generation of all of us alive right now, asking these questions that you’re raising, seeing these things that — so late, but are finally, by enough people, being seen, being taken in, if only that, right now.

Smith: It’s exciting. I mean, this is the moment — seeing, framing, thinking — before the real bubbling starts, in some ways. Or maybe we can backtrack to that. That feels like a — it’s a heavy responsibility, and it’s also this amazing invitation to participate in something beautiful, transformative.

Tippett: I would love to just wind down — we’re not going to wrap this up, but I feel like we’ve opened this up — and just wind down by maybe each of you reading a poem or two that you would like to read, that feels — that you’ve written this year, that feels consonant with this conversation, or something that will add to where we’ve gone.

Smith: I’ll go first, if it’s OK, because I’m really excited about just sinking back into Michael’s voice, and I’m really excited about his book Worldly Things that’s going to be coming out very soon. So I’ll just read one of my own poems that extends from the kind of thinking I’ve been talking about. It’s called “We Feel Now a Largeness Coming On.”

“Being called all manner of things

from the Dictionary of Shame—

not English, not words, not heard,

but worn, borne, carried, never spent—

we feel now a largeness coming on,

something passing into us. We know

not in what source it was begun, but

rapt, we watch it rise through our fallen,

our slain, our millions dragged, chained.

Like daylight setting leaves alight—

green to gold to blinding white.

Like a spirit caught. Flame-in-flesh.

I watched a woman try to shake it, once,

from her shoulders and hips. A wild

annihilating fright. Other women

formed a wall around her, holding back

what clamored to rise. God. Devil.

Ancestor. What Black bodies carry

through your schools, your cities.

Do you see how mighty you’ve made us,

all these generations running?

Every day steeling ourselves against it.

Every day coaxing it back into coils.

And all the while feeding it.

And all the while loving it.”

[Used with permission of The New Yorker, which published this poem in November, 2020.]

Tippett: Thank you.

Michael, is this book, Worldly Things, is this your first book of poetry?

Kleber-Diggs: It is, yeah.

Tippett: Congratulations.

Kleber-Diggs: Thank you.

Tippett: What would you like to read from this?

Kleber-Diggs: “The Grove” —

“Planted here as we are, see how we want

to bow and sway with the motion of earth

in sky. Feel how desire vibrates within us

as our branches fan out, promise entanglements,

rarely touch. Here, our sweet rustlings. If only

we could know how twisted up our roots

are, we might make vast shelter together—

cooler places, verdant spaces, more sustaining

air. But we are strange trees, reluctant in this

forest—we oak and ash, we pine—

the same the same, not different. All of us

reach toward star and cloud, all of us want

our share of light, just enough rainfall.”

Tippett: Well, thank you both. Thank you for letting me, and letting us, also, just experience the conversation between the two of you and, of course, your writing and what you have to say. I’m really grateful for this, and I’m very happy to have this space to put it out into the world.

Kleber-Diggs: Thank you.

Smith: Thank you.

[music: “Chilvat” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Tracy K. Smith is a professor of creative writing at Princeton University and the former Poet Laureate of the United States. She is co-editor of the book There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis.

Michael Kleber-Diggs contributed to that book and teaches creative writing through the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop and at colleges and high schools in Minnesota. His debut collection of poetry is called Worldly Things. And here, in closing, he reads a final poem from that work. It’s titled “Every Mourning” — “mourning” in that title is spelled m-o-u-r-n-i-n-g.

Kleber-Diggs:

“Morning: walking my neighborhood, I come upon a colony

of ants busy at work. I take care not to step on any and miss

them all, then encounter up a ways a fellow traveler greeting

the day. I am frightening her. No. She is afraid of me.

Is she an introvert? Is she a neighbor? Is she just in from the ’burbs,

from the country? Is she scared of the inner city? Am I the inner city?

Is she racist? Shouldn’t I be the wary one? Or is she a survivor

like me? It can’t be what I’m wearing: khakis, a blue and white

checkered button-down shirt, and the nylon sandals I favor

because they’re comfortable, my feet can breathe in them.

Dear friends, I am the nicest man on earth.

And I want to shout, Morning! But just then a weaver or

carpenter, just then a pharaoh or fire of pavement, just

then a little black ant struggles by alone, alone. And

in that moment, I want us to give ourselves over

to industry, carry the weight of the day together, lighten

it. I want to be a part of a colony where I feel easy

walking around. Cool as the goddamn breeze. Where

I can breathe, build structures sturdier and grander

than this—but the woman crosses to the other side

of the street, and I do what I usually do: retreat into

myself as far as I can, then send out whatever’s left.”

[music: “Run Outs” by Alfa Mist]

Tippett: The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, and Lillie Benowitz.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.