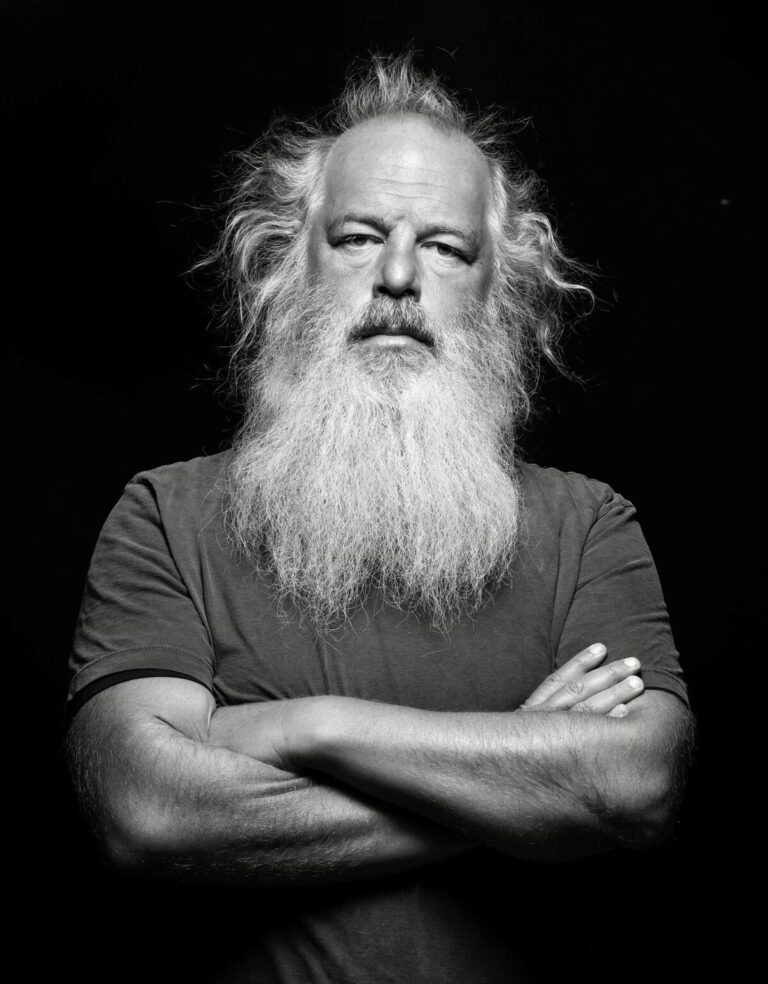

Rick Rubin

Magic, Everyday Mystery, and Getting Creative

The flow and the ingredients by which an idea becomes an offering — and life practices which call that alchemy forth. The mystery of it all that can only be named and wondered at — and the ordinary mystery that creativity is a human birthright, a way of being rather than doing, that beckons to us all, in everything we do, from crafting something to conversing to the arranging of furniture in a room.

This is where Krista goes with the rock star music producer Rick Rubin. It’s not a conversation about the creative process of the many great musicians he’s worked with — but a conversation that is for and about us all.

There are some surprises, too, in his lovely, soothing voice — like the way he finds a metaphor for all of life in pro wrestling. And he leaves the doors of his studio wide open as they speak, so there is a soundtrack of ocean waves.

Guest

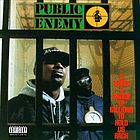

Rick Rubin has been a singular, transformative creative muse for artists across genres and generations — from the Beastie Boys to Johnny Cash, from Public Enemy to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, from Adele to Jay-Z. To name just a few. His new (and first) book is The Creative Act: A Way of Being. He is co-founder of the record label Def Jam Recordings, and former co-president of Columbia Records. He is also one of the hosts of the podcast, Broken Record.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: I’m in conversation today with the rock star music producer Rick Rubin, but I’m not really going to talk to him about music. Yes, he has been a singular, transformative creative muse for artists across genres and generations — from the Beastie Boys to Johnny Cash, from Public Enemy to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, from Adele to Jay-Z — to name just a few.

But Rick has been looking back these past few years at what he’s learned about the creative process itself, and he’s published his first book, The Creative Act, about that: the flow and the ingredients by which an idea becomes an offering; life practices which call that alchemy forth; the mystery of it all that can only be named and wondered at — and the ordinary mystery that creativity is a human birthright, a way of being rather than doing that beckons to us all in everything we do, from crafting something to conversing to the arranging of furniture in a room.

I remember the first time I saw Rick Rubin in a documentary about a record he was producing with the then-Dixie Chicks. He sat with his eyes closed, listening with his entire body. He was palpably taking them to new places in themselves that they hadn’t known how to reach.

In this hour he offers a beautiful and accessible abundance of practices and takeaways for the rest of us, too.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Rick Rubin: Our creativity doesn’t come from our ideas … Everything we do has all of ourselves in it. It can have all of ourselves deeply in it, or it could just be surface level. But either way, we’re inhabiting the things that we’re making. The good ones have our soul. You know, they have a piece of us in them.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

There are some surprises in this lovely, soothing conversation with Rick Rubin — like the way he finds a metaphor for all of life in pro wrestling. And he left the doors of his studio wide open as we spoke so you might hear a soundtrack of ocean waves.

Tippett: So one thing Rick, I don’t see much out there, I don’t know much about, just, your growing up. I mean, I know you grew up in Long Beach, New York. What is Long Beach, New York like and what was your family like and did you have siblings?

Rubin: I’m an only child. It was a beautiful little beach town, about an hour outside of Manhattan, which is a particularly interesting place to be because you’re close enough to the big city to be able to get to museums and theater and different things that if I lived in a more rural place I wouldn’t have access to. Yet, I was far enough removed where that wasn’t my experience of life. I didn’t grow up in the Manhattan bubble. I grew up in a little beach town. So in some ways I grew up in the perfect place for me to be me.

Tippett: You know, I’m always so interested in the origins of a life, the beginnings of a life. And you’re such a fascinating and complex human being. And, you know, I think the word “spiritual” is overused and too small. But you have a view of life in which transcendence and mystery are very much alive. And so I just — I wonder, where do you see roots of that, how that might have gotten planted in you in that little beach town, not far from Manhattan, in your earliest life?

Rubin: Well, I think being an only child is part of it. I had a lot of time on my own and I had very loving parents, but I spent a great deal of time alone in my room. And I read a lot and I got interested in magic, performing magic very early on. I was probably nine years old. And when you’re nine, doing a card trick or an actual miracle occurring — there’s gray area between that. The idea that there are things that we don’t understand when we see them and don’t make sense, and as a practicing magician, creating images that gave people the feeling that they were seeing something that they weren’t seeing, it blurred the line for me where reality begins and ends. And it’s still blurred.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: And I live in a world where anything is possible and I’m open to the possibility of anything, regardless of how far out it seems possibly being able to happen.

Tippett: And I would say also at this point in your life, there’s a developed philosophy and practice of supporting that, the reality of all those possibilities.

Rubin: It has turned out that way. It’s really remarkable. It’s remarkable to watch because I don’t really know what I’m doing on any level, but I trust in what’s going on in my body and the feelings that come up. And I do my best to be as true to myself as I can be. And that’s all that I’ve ever done and it has led to a very creative life.

Tippett: I think you also have a special gift to accompany others in creating that space, right? So you also have a way of doing that communally.

Rubin: It seems, yes, it has happened. Again, it’s not anything I truly understand, but I think when you really listen to someone, they act differently. And most people are not used to being heard.

Tippett: Yeah. So I told you when we sat down that I’m, we’re not going to talk about your incredible singular career as a producer, and I would even say kind of a midwife to bringing art and music and beauty into the world. But I would like to ask you, just — I mean you started Def Jam, was that in high school or college? I’ve seen both.

Rubin: That was in college.

Tippett: In college. What was it that you felt needed to be in the world that wasn’t in the world, that was in that impulse to create that for you?

Rubin: Well, I didn’t know anything about the music business or how to do anything professionally. Just, I was in a punk rock band and I made recordings of my own band. And then I hung out in record stores because that’s where you could learn the most about music and get turned on to new things. And one of the record stores I hung out in was called 99 Records. And it was a tiny little shop on 99 McDougal. That’s where it was. And it was down a flight of stairs and it was a tiny little basement. Tiny. And I would go there and hear all this European music that I wouldn’t get to hear otherwise, not anything you would hear on the radio or not anywhere that you would hear unless you went to the coolest of nightclubs, you might hear this stuff. And I would hang out there. And they put out some of their own records that turned out to be really influential. And I would ask questions about how it was done. Because I spent so much time in the store, I was friends with the people who worked there. And they walked me through the process of where you could have vinyl pressed and where you could have covers manufactured, and where you could have labels made. And they were all in different places. And I would go from place to place and gather these things and then press up a few hundred copies of my punk rock band’s records. And I did that two times.

And then I was going out to these underground nightclubs. And there was one that had hip-hop music and I would go there every Tuesday and hear this music that I loved. And then there started being some rap records coming out. And the rap records that came out didn’t sound like what the energy in the club sounded like. So I decided to start making records only as a fan and only as a — basically as a documentarian. I wanted to make music that sounded like what I felt at the nightclub, because the records that were being made were being made by professional people who didn’t really know what hip-hop was, but they were going about it the traditional way of making dance music, which was very different than hip-hop music. So that’s sort of how it started.

Tippett: You know I’m just, I’m so curious, this is a huge question, but after all these years of being immersed in music and being with so many musicians and so many kinds of musicians, I mean, it feels to me like what you just described is you wanted to capture, you wanted capture the essence of the experience.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: And how would you start to talk about what you’ve learned across these decades of where music comes from in us and what it works in us?

Rubin: It seems to have a really therapeutic effect. I think we all want to be heard and music is a way to let out our inner emotional life, sometimes in a way that can’t necessarily be understood any other way. It functions different than prose or storytelling in that the music has an emotional base to it, even without the words. So you can feel this energy and express whatever’s going on inside of you through this form. And for young people, who have a lot of energy, it’s a great outlet, because you can channel all of the power of the energy that you have into, let’s say punk rock music, which was the case when I was a kid, or hip-hop music in the case of the things I got to work on. But it was definitely at the time, very young person’s music. And it was the music of people with a lot of energy and a lot of excitement about life and not really anywhere to put it. So this was a really positive place to put it.

Tippett: It’s so interesting to think about how new generations do always bring new forms, bring new forms alive, new forms of music alive.

Rubin: It’s true. It keeps happening over and over again. And I will tell you when it’s happening, it doesn’t seem like it’s happening. You know, at the time that we were making hip-hop records, there was no expectation that anybody would like what we were doing. We were making things on an artisanal level for ourselves and our friends. That’s it. The fact that it has taken on a life of its own is really shocking.

[music: “Don’t Believe the Hype” by Public Enemy]

Tippett: And you have now been writing and you have now written a book. And is this your first book? You haven’t published a book before, have you?

Rubin: This is my first book and I’ve been working on it for between seven and eight years now. And I, I’m so excited to finally get to share it with people because it’s been a long journey. And it was a long journey for me to get to understand what’s in the book because I can’t say that it’s things that I know.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: It’s things that I notice and the things that we notice are fleeting. [laughs] So it’ll come up and I’ll make notes on the things that I’m noticing and they’ll work their way into the book. And then I can look back years later now and read some of it and be shocked by what’s there. Not because it’s not accurate, but that I didn’t know that I knew it. I don’t know it, but I recognized it in that moment, was able to capture it in that moment. And that’s, I’ll say, that’s similar to what happens in the recording studio, is we tend to record everything because often it happens when you don’t know it’s happening.

Tippett: Yeah, well that’s the magic, right? That’s the mystery of creating. RIght. And I think that’s a primary reason I write is to learn what I know. [laughs]

Rubin: Yes, that’s how it happened for me.

Tippett: [laughs] Yeah.

Rubin: And I was shocked. It remains shocking. But I’m excited that it’s there and now I can use it as a reference tool.

Tippett: Right. And you know here’s the thing, you could have — you have really stunning articulations in there I’d just kind of like to ask you to unfold. “The world is the doer and we are the witness. We [likely] have little or no control over the content.”

Rubin: Yes, [laughs] yes. It’s happening before us. We come in as a blank slate. We may have inclinations, I imagine. But what we take in over the course of our life is all that we’re filled with. So the world is going on and the creative life of the world is always happening. We get to watch it and if we choose to, we could participate. But if we don’t participate, it goes on.

There’s an example in the book of when we have an idea and we don’t execute it’s not unusual — if you have a good novel idea and you’re excited about it, but you don’t act on it, it is not unusual for, you know, six months later to see it come out in the world by someone else. And it’s not because they read your mind or they read your diary of the idea that you wanted to do. It’s because it was time for that thing to happen. And the reason you wanted to do it was the same reason that the other person wanted to do it. It was, the culture set the stage for this to happen. And whichever of us have the best antenna can pick up on what it’s time for.

And I’ll say, I didn’t know this, I still don’t know this, but it has turned out [laughs] that the reason that things that I’ve made have found their way into the world and met with interest is only because it was the right time for those things to happen. But I didn’t act on the feeling, thinking, now was the time to do this. I acted on, it’s like, now this is the time for me.

Tippett: You stepped in as it crossed your path. Is that a way to say it or — ?

Rubin: Yes. I think that’s, I think that’s realistic. I think that’s realistic. And it’s not intellectual, it’s not based on looking at any charts or any analysis. It’s only based on a feeling in me of what are the things that make me lean forward? What are the things that make me laugh? What are the things that make me excited? What do I find beautiful today that I didn’t notice yesterday? What are those things?

Tippett: And that intentionality that you just, that kind of intentional awareness that you just named, those are ways of nurturing your own — one’s creativity as one walks through the world.

Rubin: Yes. And the reason the subtitle of the book is A Way of Being —

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: — and it’s funny, we’re on On Being. [laughs]

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: The real practice of the artist is a way of being in the world. I always had assumed that it was, it was about doing things a certain way is what an artist was. But it’s more than that. Yes, there is an aspect of it that’s about doing things a particular way and in a considered way. But the only way to do things in a considered way is to live in a way that gives you the sensitivity and data that allows you to create in a curated way. You have the material to curate from. Do you know what I’m saying?

Tippett: Yeah. And even if that is rearranging the furniture in a room.

Rubin: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Tippett: Which seems to be something you do when you run out of creative projects [laughs].

Rubin: It’s something I do. Sometimes I’ll visit, if I visit a friend in an office and I’ve never been to their office before, it’s not unusual for me to rearrange the furniture in the office.

Tippett: [laughs] Okay. I like that, I think that word “curate” is important. One of your points is that we all have it in us to be creative all the time in anything we’re doing.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: Many of us hesitate to call those things creative. Or even — right? And then I think even when I say — I’m going to say those of us who have projects we call creative, right? Which is also fraught with self-doubt and wondering if it deserves that title. One of the things about more formal projects we’re calling creative is this interplay between openness and discipline, playfulness and structure. There’s all kinds of advice [laughs] about structure to create, about schedules. And the process of being creative and being open feels like it often stands in this terrible tension with all of that, right? I think you’re saying, with the getting things done. I think something in the way you came at this, that was, that just kind of shifts it is, because you said, “Awareness needs constant refreshing,” and that that in fact is the point of habits and rituals.

Rubin: Absolutely. The practice of staying tuned in, that’s one of the practices. The other is the good work habits, which are — and it is, it’s funny, there’s a tension between the idea of everything we’re doing is playing, which it is.

Tippett: Yeah, no, it’s this very confusing tension.

Rubin: But I’ll say that I learned something through the book, which is when I realized that not all of the four periods of work — so it starts with the seed phase is the first phase, and the second phase is the experimentation phase, the third phase is the craft phase, and the fourth phase is the final completion editing phase. And I’m a very good player [laughs] and was historically not a great finisher. It was always hard for me to finish projects.

Tippett: [laughs] Okay, well this is good to know. That will be helpful for people to hear.

Rubin: Yes, yes. It’s hard for me to finish projects because I always see the possibilities of what else we could try and I want to try everything, and I’m exhaustive, always, in what’s possible. So it’s hard for me to get things done. What I came to realize is that there is a time for this open play. And it’s in those first two parts of the process, the seed phase…

Tippett: Seeding and experimenting.

Rubin: … and experimenting.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: Those are really open. And I think the idea of saying, well, I’m going to come up with an idea and I’m going to execute that idea and I’m going to finish it…

Tippett: Implement, right.

Rubin: Yeah and I’m going to finish it by this time. Before you’ve collected the seeds seems like a bad idea. The chances of it being good seem limited.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: But once you have the seeds and once you’ve experimented with the seeds and you get to the craft phase, which is where you’ve already cracked the code of what it is, and it gets down to the actual grunt work of bringing it into the physical world, all the ideas are worked out. There’ll still be more small decisions to be made along the way and it’ll be a creative process all the way through. But you know what you’re making and you have a vision for it.

Tippett: You know, I think it’s important to name here, when you talk about “what I learned from the book,” my understanding is that the process of writing all of this, of thinking it, of putting words around this was really about going back across your decades of working with the creative process of all kinds of different people, including your own and then kind of reverse engineering: “what did I learn about how this works?” Is that right?

Rubin: Yes. That is right.

Tippett: When you say — you literally were, the book was teaching you what you had learned.

Rubin: Yes. I realized through thinking of the phases of work as phases. Once I understood that, I never thought of it that way before. In the past, it was always: you start and you work until you’re done. And it has to be open-ended because that’s the only way you get to make anything good. So based on that, I realized, okay, we can start having really realistic expectations of ending things once we’ve gone through this process and we’ve done all of the open playing to the point where we have things that we love and we have a vision for the whole thing. And now it’s only a question of the final crafting, editing, and sharing that’s left. If we do that with a schedule, it’s actually helpful to the project. Whereas before I would think it would be, it would get in the way of it being all it could be. Now, I think getting on schedule at the right time in the process can be really helpful.

Tippett: Which is probably why it’s helpful to have the right partners and coach. Because what you’re also dealing with in all of these phases, and this runs through everything, is how the human condition interacts with the creative process, right?

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: I mean, of course it can go unexpectedly well or unexpectedly badly at any time because we are very strange and complex. And you are so attentive to how memories and emotions and the subconscious are also acting at all times when we are open to this part of ourselves.

Rubin: It’s all part of it. It’s all — we never know where it’s coming from. Sometimes we know if we’re responding directly to something that just happened, we know where it comes from. But often the way we respond to things don’t, it doesn’t always make sense. We might not know why something makes us feel a certain way. That happens — I tell a story in the book about watching, there was a documentary I was watching about AlphaGo.

Tippett: Yes. I wanted to. Yeah.

Rubin: Yeah. And it was fascinating.

Tippett: And explain it. So it’s this game.

Rubin: It’s — Go is an ancient game. It’s been played for 3000 years. It’s a board game like chess, but it has more possibilities. There are more possibilities in the game of Go than there are grains of sand on the planet. It’s the most difficult of all games in terms of predicting an outcome. And where we’ve had computer chess for some period of time, the idea of AI Go was a dream of the programming community and the AI community that would be a real benchmark. If the AI could play the game of Go as good or better than a grandmaster, that’d be a remarkable shift. And it was believed to be impossible.

And I watched a documentary about this where the AlphaGo experts finally got the program to the point where they thought that it could beat a grandmaster. And they had a competition between the Grandmaster and the machine. And at move 37 in this game between the Master and the machine, there were two choices. It was the computer’s turn to move. If you’ve played Go at any point in your life, or certainly if you were a champion or a commentator, you knew that there were — based on the move that went before you — there were only two moves that the computer could make.

And the computer ended up not making either of those two moves but a third move that was basically viewed as a mistake. The Grandmaster who was playing the game got up and left the table. He was disgusted.

Tippet: Right.

Rubin: And the announcers who were the expert announcers were like, “Oh, the computer, it screwed up. It doesn’t know what it’s doing. It can’t be that, that’s a wrong move.” And then eventually the Grandmaster comes back, they finish the game, and the computer wins the game.

And I hear this story and I realize that I’m crying. And I don’t understand what’s going on. I don’t know, why am I crying? Am I crying — The surface answer would be, “Oh, the machine has conquered man and we’re all in trouble.” It’s doomsday, right? That would be one…

Tippett: Right. No, I want to say, I was going to ask you about this cause it was a stunning thing to read.

Rubin: Yes. But I didn’t have that feeling at all. That’s not what it was. So I’m crying. It’s like, well I don’t care if the machine wins or man wins. Why am I having an emotional reaction? What’s going on? And I thought about it for, I think I realized what it was on the same day, but it was hours later. I was thinking about it for hours. Where is the emotion in this for me? Where’s the emotion? And eventually, it clicked.

It was about creativity, which I take very personally and emotionally. So that’s why. I was crying because it was about creativity. And that the computer made a creative choice that man wouldn’t have made. And the reason the computer made the creative choice was not because the computer was smarter. It was actually because the computer knew less. The men playing knew — not only did they know the rules of the game, but they also knew the traditions of the game. And they knew the whole history of the game, of what every great player had done before. And they knew what they learned in the school of playing. The computer was only playing by the rules of the game because it doesn’t know the cultural norms of the game. So the fact that man’s own baggage of beliefs…

Tippet: Right.

Rubin: …of thinking we know best is what was holding man back.

Tippet: Yeah.

Rubin: And the computer was what showed us that. And I thought it was so beautiful because that gave me hope for everything. That means there’s so much that we think we know that we don’t know. And maybe the computers can help us remove the distracting information that we hold true…

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: …that’s stopping us.

Tippett: I want to kind of come to some of the very concrete and available practices that you offer, just to have a practice of awareness towards that state you’re talking about which somewhere you say the, it’s about learning “to learn and be fascinated and surprised on a continual basis.” And of course meditation. But also, a day walking in nature. I don’t know, you’ve talked about before you go to sleep “noticing the feelings of your heartbeat and the movement of your blood.” And you said, “The purpose of such exercises is not necessarily in the doing, just as the goal of meditation isn’t in the meditating. The purpose is to evolve the way we see the world when we’re not engaged in these acts.”

Rubin: Yes, and by learning to meditate when I was young and having that practice — and it’s the nature of meditation— your life off the cushion changes. And it changes because you’re building a new reality within yourself. A new, I’ll call it like an emotional musculature, that is more in tune with the present as you are experiencing it in this moment. And not the distractions that the world is bombarding us with, but a wider, more open, more generous … I don’t know how to say it. I guess we’ll go back to the curation. Just being able to see more and curate the best of it for ourselves to be able to then use both in our lives and in our work.

Tippett: Here’s a really striking sentence also: “The beauty around us … is an end in itself.” Right? All of this stands in a contrast to a lot of the ways we’re conditioned, right?

Rubin: Yes. Yeah. getting out of our own heads. Getting out of what we were told, you know? Getting out of what we were taught. Being free.

Tippett: We’re so purposeful. [laughs]

Rubin: Yeah, being free to experiment.

Tippet: Right.

Rubin: Being free to have fun and experiment. And if we find a new way to do something, to embrace it instead of thinking, “oh, that’s the wrong way.” You know, the reason, the reason that I made the hip-hop records that I made, I made them the “wrong way.” I didn’t have the baggage of the “right way.”

Tippet: Right. [laughs] Okay.

Rubin: So there’s some great benefit in — do you know what I’m saying? Out of, I think I even used the word “ignorance” in the book. There’s great wisdom and ignorance.

[music: “Scratcher” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Okay, this is just another little anecdote, but it fascinated me. And I want to say, where does this fit in, right? So there’s the openness and then there are, you use the language of “sustainable rituals.” Rituals are so important here, even in an ongoing conversation with and almost a partnership with the openness and awareness, right?

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: You tell this story of John Wooden.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: I guess, what was he, one of the greatest college basketball coaches ever.

Rubin: Yes. He was the greatest college basketball coach in history. The most winning coach in history. And this is college-level.

Tippet: Yeah.

Rubin: So most of the players have been playing for some time already. By the time you get to college, it’s pretty serious.

Tippet: Yeah.

Rubin: And so the best players from all over the country can’t wait to get to be coached by the great John Wooden. And they get to practice the first day, first time. So these are students from all over the country, the best players in the world [laughs] get there and he spends the whole first practice teaching everyone how to tie their shoes. And you can imagine…

Tippett: Put their socks on [laughs].

Rubin: Yeah. How to put their socks on properly and how to properly tie their, lace up and tie their shoes. You know it’s so — And it would be like a kindergarten class. But his point was that every detail matters. And it’s not the best way to do the extreme version of what you’re doing, it’s how you do every step, every piece leading up to it. All of the practices involved.

Tippett: Right. And then I, we have to name again, well the human condition itself is complex. And then when we’re being creative, when we give ourselves over to this, when we open, there’s incredible vulnerability in that, right? And there are, there’s what Buddhists would speak of as the monkey mind. There’s the critic over your shoulder, right? There are many different ways to talk about this, but it’s a very well-known phenomenon. I mean, you know, even when you speak of the creative, just this hugely important part of the process before you can actually implement or execute, is experimentation. But experimentation also entails imperfection and impasse and…

Rubin: And failure.

Tippett: …and failure and getting things wrong.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: And yeah. So what have you learned about how to work with that?

Rubin: It’s helpful to think in terms of: it’s only play. We’re here to play. We’re here to have fun. And to use the feedback of, you know, sometimes failure is the thing you need to know to get to where you’re going. So if you try to solve a problem 10 ways and they all fail, you can either decide I’m a failure or you can decide, okay, I’m now 10 methods closer to finding the solution because I’ve ruled out those 10. And that really is our work is we’re constantly ruling things out. We’re trying things with no expectation.

That’s another part of it is like, let’s try things without putting any pressure that we think it’s going to work or we hope it’s going to work or we need it to work. No. We don’t work like that. We work where we’re having fun trying things and let’s see what makes us laugh. Let’s see what makes us want to try it again. You know, what’s the most fun version of the game? Or what’s the most interesting version of the game? And when it happens, it’s exciting when it happens.

Tippet: Yeah.

Rubin: And sometimes it’s like fishing. You bait the hook and you throw the line in and you’re waiting and you’re waiting and you’re waiting and nothing happens. And we can’t control that. The only thing we can control is deciding, okay, I’m going to keep going fishing until I catch the amount of fish that I want. I can’t control the time schedule that that’ll take. But I know the only chance of me catching three fish is for me to continue fishing until I catch three fish.

Tippett: Well, so I — something that is very important to me that I don’t, that I hope, I endeavor to be able to create more space in my life for is writing as a creative act. And I’m very drawn and driven to do this, but I’m pretty tortured [laughs] when I’m doing it. And an experience I have had again and again that is very unsettling is that when I’m — especially in those early stages — that I have learned not to trust knowing what is good that I’ve written. And sometimes I will write something, and I’ve heard other people talk about this thing too, about writing something. And I think, and it’s almost if I think immediately, “Wow, that was really great. That’s it.” It’s not. It will be the thing that I will look at and cringe. And then there will be these quiet paragraphs that I don’t pause over and don’t consider a great accomplishment that later will be the thing that survives. So there’s this inability to judge —

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: To assess, which is really unnerving.

Rubin: Yes, absolutely. One thing I would suggest, hearing that story, I would suggest write as much as you can and don’t look back at it. Just write. And at some point down the road, after you’ve done a lot of writing [laughs], then go back and start reading it. Hopefully by the time you forgot what you’ve written.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: And then see what’s good, because you’ll be approaching it more like a reader would, you know, you won’t be the writer anymore. You’ll be the reader.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: And I think when we’re the writer, it’s much harder to be able to assess it. But in time we can become the reader.

Tippett: Yes. And I know also that, you know, I’ve seen artists speak of working with you, musicians speak of working with you, there are documentaries of you working with people, and it’s clear that — and I think mean we all have this as human beings and we have it when we’re trying to be creative — our shadows arise. Our emotions…

Rubin: Yes, absolutely.

Tippett: …can get out of control. And you end up working absolutely very intentionally. And here’s some things you wrote that just were really helpful to me about, you know, you were talking about memories. Because they’re with us and they become raw materials, but you said “Memories can [also] be thought of as dream-like.” Because in fact, they are “more a romantic story than a faithful document of a life event.”

You also kind of, I don’t know, prescribe practices about releasing emotions, like beating on a pillow for five minutes or keeping a dream journal. I mean, are those practices that you learned, you have learned in these decades in the course of being present with creativity and to so much creativity?

Rubin: Yes, and I’ve done a lot of work on myself therapy-wise and had a lot of help and studied a lot. And I’m a very sensitive person. So one of the things that I get by working with sensitive artists, we resonate together in that we’re feeling things that not everybody else is feeling. And they could be very painful. And for someone who’s less sensitive can view how we’re feeling it as, oh, they’re — they don’t understand.

I know, I can, I won’t name the names, but I can think of one great rock band, great band, one of the great bands of all time. And two of the members of the band have different worldviews. One of them is very intellectual and the other is very emotional. So they’re experiencing the same info — data coming at them. And one reacts in an intellectual way, and one reacts in an emotional way. And they can’t even talk about it because it’s like they’re speaking two different languages. And the band has broken up because they can’t hear each other.

And to some degree, that’s the case with all of us. We all do our best to communicate with each other, but we don’t really, I don’t believe language is accurate enough for it to really represent what’s going on inside of ourselves. And it’s one of the beautiful things about music is that there’s so much more in it.

If I tell you a story, you are hearing it through your interpretation and your life experiences will give that story, my story, a certain meaning that may be very different than mine. It’s true too with getting advice. You know, when we get advice from people, experts. They’re giving us advice based on their life experiences. I can give you an example in my life. I’ve been lucky to be around some very successful music moguls, elders, you know?

Tippett: Right.

Rubin: Thirty years older than me, experts for a long time. And all of their advice is their best advice. And it’s really good and really honest and sometimes it’s really helpful to me, and sometimes it’s not. Not because their intentions are bad, but because my life experience is different than their life experience and their advice is based on their own set of data. And mine’s different. And all of ours is different. So, so many of our problems have to do with miscommunication and not really hearing each other, or not really under — or first not hearing each other, and then not understanding each other.

Tippett: And I think something that’s weaving through this is that actively, I don’t want to say becoming, but giving yourself over to being creative, to this way of being that is a creative life, gets intertwined with developing yourself as a human being.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: I mean, I was watching, I think it’s the singer James Blake interviewing you.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: Maybe for his podcast and just mentioning as an aside, how you had him watch a Marshall Rosenberg video about non-violent communication, which I think many people would not imagine that that would be part of the making of a record. Right?

Rubin: No, it was unusual. [laughs] It’s not standard. But it’s standard in the way that — the way that I get to work with artists is like we’re friends hanging out and talking about whatever comes up. And through that, things get unlocked that allow writing and performances to be more closer to the core. And that’s the goal with all of this.

[music: “Scam the Public” by subtext]

Tippett: Some of this comes back to the, what sounds like the simplest and what in fact is the work of a lifetime developing “beginner’s mind,” right? Presence, awareness, which then allows one to constantly be growing and being surprised and fascinated and learning. And I wanted to ask you, as I was walking through this, I mean, you have become a father and that is the ultimate witness to a new human being in the world, and that beginning of a life, and of a mind.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: And I’m just curious about how this experience has flowed into your thinking about all of this.

Rubin: I’ll say, it’s just really fun. I don’t know yet — at this point, I can’t tell you how it interacts with my creative life, but I’ll say it’s really fun and he gets so enthusiastic about things.

Tippett: Yes.

Rubin: And you can see, and he’ll also get very emotional at the drop of a dime. If something goes wrong, he’ll really react. And you can really see the humanity in him, you know the animal reactions. He hasn’t learned yet how grown-up people react to things. So the way he’s reacting is purely an inborn response and he can’t be wrong. Do you know what I’m saying? There is no wrong in that. It’s a pure reaction.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: He’s not second-guessing himself. He’s not comparing which version to go with. It’s a pure reaction, and it’s real, and it’s beautiful. And I guess what I’ll say is I’d love to be as open and free as he is.

Tippett: Yeah, and don’t you think that also becomes kind of a gift that we receive when we become parents that we get to walk, we don’t get to be children again, but we get to walk alongside childhood again.

Rubin: Absolutely.

Tippett: Something you talk about a lot is patience. I mean it’s both — you speak of it overtly, but it’s also implied in a lot of this, right? The seeds and the experimentation and this is not something where you rush to the deadline. And that contrasts with what we feel we’re supposed to be doing. I think for me, my children with this, these virtues, these really, these great virtues, spiritual virtues, and all the traditions, like patience, like humility.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: They actually — what I think I saw in my children is they’re actually about presence, right? Because, and a child is, it can take an hour to walk from one corner to the next because they’re paying such close attention to everything. And so it takes as long as it takes.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: It’s about being amazed at everything else [laughs] or being ready to be amazed, right? At everything and everyone else.

Rubin: Yes. And the image of the child walking and picking up everything that they see that’s interesting to them or wanting to stop and look at it, is beautiful. And I think what patience is really about is our relationship to time. And I think a child’s relationship to time is much more rooted in reality. I think we have a…

Tippett: Yes.

Rubin: We’ve put an overlay of an expectation on time. And that also goes for the time that we put into a project. Most of us think if I get a project to a certain point, and now if I work on that project for another six hours, or if I work on that project for another six weeks, or if I work on that project for another six months, well it’s either six days, six weeks, or six months better. And that’s not the case.

Tippet: [laughs] Right.

Rubin: There is no connection between the amount of time invested and how good something is. Now, that doesn’t mean that it happens quickly. Sometimes it happens quickly and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it takes forever.

Tippet: Right. Right.

Rubin: So again, it’s all complicated because there’s so much tension in each of these ideas. It’s — you need great patience. And we have no control over time. And putting time into something isn’t what makes it better. And you have to give everything all the time that it needs for it to be as good as it could be. All of that’s true.

Tippett: Yeah. [laughs] And I think maybe the point, or just not a point, but a byproduct of understanding that the core discipline is constantly refreshing awareness that “the beauty around us … is an end in itself” — I’m quoting you — is that, that is not labor, right? How we orient ourselves to this is what matters, is what makes it life-giving.

Rubin: Absolutely. And if we pick a practice like deciding we’re going to watch the sunset every day, that’s a beautiful practice. How is it similar day-to-day? How is it different day-to-day? Making the commitment that we’re going to put ourselves in a place where we can see the sun setting every day. It’s a beautiful practice. And there’s a million to choose from [laughs], there’s a million to choose from.

And that’s, when I talk about sustainable practice, we can decide, okay, I’m going to train in the gym for three hours a day. I know, knowing myself, that’s not going to happen.

Tippet: Right.

Rubin: So I can make the commitment, I can do it once and then twice I can either get too tired or hurt to be able to continue, and then that’s gone.

Tippet: Yeah.

Rubin: So the sustainable part of the practice is: start with things that are easy to do. Start with something where you can do — I’m going to wake up in the morning, I’m going to do three deep breaths. I’m going to pray before eating. It’s easy to do if you choose that. Right? I’m going to do a three-minute meditation and you can pick what’s the thing that’ll key it off of.

Oh, there’s a beautiful book, a teacher named Richard Rudd, who’s written several books that, his big book is called The Gene Keys. And in one of his books he teaches a meditation, I think it’s called The Triple Flame Meditation, where you do one minute of awareness practice on every third hour. So you do it at noon, at three, at six, at nine. You know, if you’re awake, you do — and it’s just one minute and whatever’s going on, even if you’re driving, you can still do a dedicated minute of awareness while you’re driving. You don’t have to pull over to do it.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: It’s just really being, you know, knowing that it’s 60 seconds of true awareness. It’s beautiful. It’s a beautiful practice.

Tippett: It’s also how Muslims who have this five times a day, right? This rhythm.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: This prayer. This way the day is then, it’s structured around this thing rather than deadlines.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: So I mean think we’ve circled back to the mystery of this. You use the language of the ecstatic. The magic is what we’re back at, right?

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: We’re dealing in a magic realm. This is, nobody knows why or how it works. And I’ve spoken, oh, across the years to various, also, especially songwriters. I remember Rosanne Cash saying to me — but I’ve heard other people say it in similar ways — it’s like, it’s not like you write the songs. It’s like you catch the songs.

Rubin: Yes.

Tippett: It’s like, and that if you don’t catch it, somebody else will.

Rubin: Yes. It’s channeling.

Tippett: And you’ve seen that a lot?

Rubin: It’s how it all happens. All of it happens magically and automatically. And the stories we tell ourselves about us doing it, it’s just stories. We’re part of it. If we’re not there, it doesn’t happen through us.

Tippett: Right.

Rubin: We’re definitely a piece of it, but we’re only a part.

Tippett: I would like to lightly touch down on your love of pro wrestling, which is fascinating to me [laughs].

Rubin: [laughs] That’s so funny.

Tippett: Which somehow you make a metaphor for all of reality and how the world works. So please, [laughs]. Okay?

Rubin: Okay. Wrestling is a — it’s an American art form. It’s a unique American art form where like ballet, there’s a physical performance going on and it’s often good versus evil in these stories. And unlike, let’s say, boxing, the two performers in the ring who are opposing each other are working together to put on the best show that they can. No one is trying to hurt anybody else. As a matter of fact, they’re trying to protect each other. That’s their job, is to protect the other person in the ring. So from a non-violent standpoint, I like watching it because it’s like, again, it’s more ballet.

Tippett: It’s theater. Yeah.

Rubin: Yes. It’s pure theater. All it is is theater. And there’s something interesting because they’re playing themselves, often they’re playing themselves, but they’re a character. And so real life…

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Rubin: …bleeds into the stories. So it’s scripted and someone gets injured. Not because anyone’s trying to injure, but they’re doing acrobatics. So someone’s leg gets broken. And now as a fan, we’re wondering, okay, is their leg broken in real life, or is their leg broken in the story?

Tippett: Right.

Rubin: Because we never know. Yes, it’s a plot point in the story, but we never know what are plot points and what’s real. Because when real things happen, they work them into the story. They have to because if someone’s going to be out for three months, they got hurt.

So it’s funny because people don’t like wrestling because it’s fake. But that, what I just described, where we’re all ourselves and we’re playing characters in the world —

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: And where real life interferes with the characters that we’re playing, and we never really know when we see a story on TV, on the news, let’s say [laughs], we never know where’s the performance and where’s the reality? Where’s the crossover?

Tippett: Yeah, it’s brilliant. And sometimes we’re playing ourselves and we can’t tell the difference.

Rubin: Absolutely. We don’t know. So I say I love wrestling. One of the reasons is it’s the closest thing to what reality is, is this fake sport. This fake sport is the closest thing to what reality actually is. More so than the news or a documentary [laughs] or any of the things that we accept as this is what’s really happening.

Tippett: That’s great. If I asked you, this is a huge question, so just how you would just start answering it right now. Just start answering, like through this life you’ve led, these passions, you have these things you’ve learned. How does your understanding of what it means to be human, how is that evolving even right now, today?

Rubin: I had some feelings this morning. Let’s see if I can remember what I was feeling this morning. Because I feel like it’s related to this, which is unbelievable. I mean, the odds that I’d be thinking about something related to this morning. Is that so many of the examples I’m giving are of — there’s a story and I’m saying maybe that story’s not the right story. There’s a different story. And now I think maybe all there is is stories. And to think about which is the right story is maybe a waste of time. And to enjoy the story that speaks to you. And that’s really all we do anyway. I mean regardless. Do you know what I’m saying? We don’t have to convince anyone of anything. We can just enjoy what we enjoy. And I guess being human is enjoying what we enjoy and sharing what we see.

Tippett: Here’s a last koan, it’s the last time I’m going to give you your words back to you, but I just love this so much. And it’s mysterious. It gets at that magic thing. “Not all projects take time, but they do take a lifetime.”

Rubin: Yes. And that speaks to the fact that everything we make is the sum total of everything we’ve learned and done. We’re not — our creativity doesn’t come from our ideas. All of everything in us comes from somewhere else. And we get to take those elements, and I think I use the word in the book, re-present. We have this information, and we get it, and we get to mix it up and reform it and re-present it back to the world. And sometimes we re-present it back to the world in a way that no one’s seen it before. And it’s exciting. And someone else can see the thing that we share that hadn’t occurred to them before in that form. And that inspires them to make something — it opens a door in them that allows them to see, oh, it doesn’t have to be the way I thought it was.

Tippett: Yeah.

Rubin: It’s being inspired by a way of seeing the world that allows you to know, oh, my choices are wider than I thought. I was going straight really fast and then someone made a left turn. I didn’t know you could make a left turn. Maybe I can make a right turn. I haven’t seen anyone do that. Maybe I can go up, maybe I can go down. But once someone breaks the straight line, moving straight forward, it opens up so many possibilities for everyone else.

Tippett: And the totality of our lifetimes is pouring in when we make those choices, whether we know it or not.

Rubin: Absolutely. That’s where it comes — it comes from everything we do has all of ourselves in it. It can have all of ourselves deeply in it, or it could just be surface level. But either way, we’re inhabiting the things that we’re making. The good ones have our soul. They have a piece of us in them.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Rick Rubin’s book is The Creative Act: A Way of Being. He is co-founder of the record label Def Jam Recordings, and former co-president of Columbia Records. He is also one of the hosts of the podcast, Broken Record.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Romy Nehme, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Juliana Lewis, and Tiffany Champion.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections