Valencia Robin

The Coup

Valencia Robin’s poem portrays a tense relationship between mother and daughter; perhaps each resembling the other too much. In desperation — and shock — the daughter says the worst thing she can think of to her mother. What follows is like the fall of a dictator, a coup, an end, an opening.

We’re pleased to offer Valencia Robin’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

Image by Annisa Hale/ Film processed by Moody's Film Lab, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

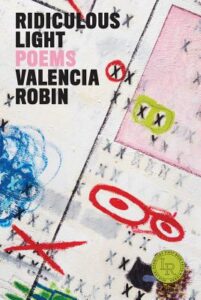

Valencia Robin is an interdisciplinary artist whose practice includes poetry, painting, collage, and sculpture. A recipient of a National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship, her debut poetry collection, Ridiculous Light, won Persea Books’ First Book Prize, was a finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and was named one of Library Journal’s best poetry books of 2019. A co-founder of GalleryDAAS at the University of Michigan, Robin has an MFA in Art & Design from the University of Michigan and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Virginia. Robin currently teaches at East Tennessee State University and lives in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama and I have a vivid memory when I was a teenager — maybe 16 or 17 — my father came into the kitchen. And our relationship was tense at the time and he was so hungry, he must have had a complete blood sugar drop or something, and he grabbed some bread and ate it like a starving man. And I remember noticing his hunger and being shocked out of whatever battle we were caught in and just seeing him for his hunger. And I went and wrote a poem about it because I didn’t know what to do with seeing his need so clearly in front of me.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The Coup” by Valencia Robin

“My mother in all her armor

which so rarely came off—her laws, her decrees,

her look that said, Don’t ask me for anything

before I could ask for anything, that roared

Off with her head! when I asked anyway.

Thus once—in a rare show of defiance—I said,

Then I want to call my father.

And even now I can’t believe the words came out of my mouth.

My father, a man my mother had never acknowledged,

whose absence was treated no differently in our house

than, say, not having a cat or washer and dryer.

She looked terrified, like a dictator threatened with a coup,

like a lonely despot betrayed by her most trusted servant,

like a single mother, catching three buses to work,

no idea how she could be the bad guy.”

[music: “Cicle Gerano” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This poem, “The Coup,” comes from Valencia Robin’s book, which is called Ridiculous Light. And the book is dedicated to her mother. And so, this poem feels like it comes with a particular weight. The dedication to the mother at the start of the book sets the tone of the relationship up in a particular way and then as a life is narrated — and these feel like very autobiographical poems throughout the book, lyric poems, narrative poems — this poem, “The Coup,” sits there with heavy language. It’s kind of funny, but then you read it again and go, it’s kind of not.

[laughs] And I’m always caught between the two experiences of thinking, “What was going on?” And then being hugely entertained by the power of the language in it.

Valencia Robin is a renowned artist as well in all kind of forms of visual art. And the visual nature of this poem just brings us right into seeing everything that’s there — the emotional reality, the memory reality as well as the visual reality that’s there.

And combat is everywhere in this poem: “All her armor / which so rarely came off,” we hear, in the very first line of the poem. And then “her laws, her decrees, / her looks.” And then “roared / Off with her head!” That’s a line perhaps repeating what the Queen of Hearts from Alice in Wonderland says. And then “a rare show of defiance.” There’s no getting away from the fact that there’s not a lot of affection used in the way that this poem describes the mother.

Sometimes I think that the point of view, the age of the speaker of the poem is of an age where ultimately they’re really wanting their own independence and needing to get out and perhaps really resembling the mother. This might be a mother-daughter pairing where they are so similar that there needs to be some kind of martial law in the house in order that there’s going to be a truce between them. Or not a truce — where everybody knows who’s boss. But something is brewing. Who knows? This could be something that’s said with great affection in the sense of, “You were a you were a hard ass.” Or this could be something that says, “Actually that was tough.”

What I love about the poem is that it holds that. It doesn’t apologize for it either. It says it can be tough to be the child of a parent. And perhaps, too, it can be tough to be the parent of a child, especially in those years when independence is rising. And the poem makes no apology for the heightened combat metaphors that’s the whole way throughout it.

[music: “Calisson” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This poem builds and builds towards a certain amount of similes at the end. And simile is one of the oldest technologies that is around in poetry. And a simile is where you say, this thing is like that thing. Draws a comparison or similarity between what’s meant to be two unexpected things, and certainly, there is something unexpected about referring to her mother like a dictator or a despot. [laughs] Maybe referring to herself as the most trusted servant of the mother, as well. There’s a really clear indication of a direction of power in the way that the similes are being used.

I think that the poem, too, is trying to figure out how does the younger person, the daughter in the poem, looking at her mother, how does she think, “Well, she’s probably somebody else outside of here.”

At the end of the poem, the way that simile puts unexpected things next to each other, mother-dictator, mother-despot, that’s changed. Mother, like a “mother, catching three buses to work.” Mother, “like a single mother, catching three buses to work.” And then suddenly we’re in the mother’s mind: “no idea how she could be the bad guy.”

In the last line of the poem, we’re caught in the conundrum of the mother who’s thinking, “Am I the dictator? Am I the one staging the coup? Do I deserve to have a coup staged against me?” And even deeper than that, then, “Who am I? And who am I with my daughter? And who am I with myself? And who am I in the world? And what has my life become?”

This poem opens up these huge existential questions in the middle of an argument between them where the daughter has used, it seems, the one thing that she knew could topple the mother. “Then I want to call my father.” And the father is notable in the sense that he’s not a character at all in this poem. He’s just used as a weapon. He’s used as a bullet. He’s used — his absence is used — as something to topple a certain practice of power.

[music: “Great the Contessa” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This is a poem of recollection. “My mother in all her armor,” it starts off. But there’s a couple of times in the poem when you hear that the poet is looking back and remembering herself. And one of them is just after she’s recollected how she said, “Then I want to call my father.” Time changes. Valencia Robin says, “And even now I can’t believe the words came out of my mouth.” And then it goes back into the narrative of the poem and everything that unfolded in front of her between herself and her mother after she’d said that.

Who’s looking at who here? She’s looking at her mother. She’s looking at the woman her mother was. She’s looking at the child she was or the teenager she was. And she is also thinking, “How on earth did I say that?” Maybe “how did I know to say it? And how did I get away with saying it?” Because this is a home where it’s clear that there’s power.

I think this is a poem that’s classically exploring liminality. Liminality comes from the word liminis, which is the word for threshold, which is the space between two rooms, perhaps under the door where you can look one way and see one room and another way and see another room.

I happen to despise the word liminality with every core of my being. I think maybe because I’m Irish sometimes people say to me, “Oh, can you talk about liminality?” And I feel like they want me to be some kind of mystic leprechaun. But what I think is really important about liminality is that it’s absolutely concrete. It is about being torn sometimes and seeing options and thinking, “I turn this way and I see this vista. I turn the other way and I see another vista and I’m caught in between.”

The word liminality in Irish refers to your wrist or your ankle, the narrow place, which is absolutely necessary but also open to great pain if you strain yourself in the wrist or in the ankle.

And this poem is a liminal poem in the truest sense of it — because we’re caught. The poet is saying, “How can I have said that to her? Was she a dictator or was she my mother?” The mother in the poem, too, is thinking, “Am I the bad guy? Or am I doing a really good job holding everything together at home and catching three buses to work?” This tension, the threshold of the poem is people wondering, “Who am I with myself, with each other? How do we do this? And how do we hold all the power together?”

[music: “Creatures of Myth” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem doesn’t wrap up the relationship between the mother and the daughter neatly or easily. How it does wrap it up is muscularly with the question remaining in the mother’s mind of how she could be the bad guy. “No idea how she could be the bad guy.” We’re brought into the narrative of the mother’s life, “catching three buses to work” and “a single mother, catching three buses to work,” wondering about how it had turned out like this.

That is a certain form of resolve that leaves us in tension. And I think, though, by placing that information about the mother’s life right at the end of the poem, what I think we hear is the fact that the poet is older now, reflecting on her mother’s life, reflecting on what was she putting up with, and perhaps holding herself to the light as a younger person, saying even if the relationship wasn’t easy, here is something that she weighs more heavily than the difficulty that it might have been of being this woman’s daughter. She leaves us at the end of the poem with the data about the mother, her determination, her employment, and her commitment to her daughter. The threat and the love, the promise and the loyalty, all together in the same poem.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The Coup” by Valencia Robin

“My mother in all her armor

which so rarely came off—her laws, her decrees,

her look that said, Don’t ask me for anything

before I could ask for anything, that roared

Off with her head! when I asked anyway.

Thus once—in a rare show of defiance—I said,

Then I want to call my father.

And even now I can’t believe the words came out of my mouth.

My father, a man my mother had never acknowledged,

whose absence was treated no differently in our house

than, say, not having a cat or washer and dryer.

She looked terrified, like a dictator threatened with a coup,

like a lonely despot betrayed by her most trusted servant,

like a single mother, catching three buses to work,

no idea how she could be the bad guy.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “The Coup” comes from Valencia Robin’s book Ridiculous Light. Thank you to Persea Books who gave us permission to use Valencia’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, Annisa Hale, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.