Image by Andrés Guzmán, © All Rights Reserved.

Knowing Is Belonging

I am not an easy joiner. I never belonged to a sorority; I didn’t volunteer for my kids’ school PTA or my apartment building’s Co-Op board. I quit a short-lived book club, never sign up for alumni events. I don’t find myself needing groups — especially in this modern moment, when groups are available everywhere without leaving the house: one joins simply by watching and “talking” about the same TV series, movie, album, or book; by sharing photos, articles, songs, stand-up routines, and personal updates on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or by attending a show or concert with hundreds of other fans. I have plenty of belonging if I want it in that sense — being part of a virtual (or actual) cultural or political conversation.

But one group has come to matter more than I expected, certainly more than it ever did growing up: belonging to other Jews. I always knew, and felt positive about, my religious affiliation; I celebrated a smattering of holidays and was aware of a responsibility that came with being Jewish because so many Jews were killed throughout history. My ancestors were persecuted, so who was I to shrug off the identity that had made them targets? But a Jewish mantle of guilt can be more burden than inspiration; I hadn’t yet discovered the spark of a tradition that still speaks to us urgently now.

And then I did. By starting to study Torah for the first time. By joining a synagogue for the first time. By interviewing famous Jewish Americans for a book, in which I asked public figures such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Steven Spielberg what being Jewish meant to them, or didn’t. I discovered belonging by traveling the country when this book came out — to visit hubs of Jewish life, which prove to be, in many ways, more cohesive than the millions who wake up Jewish just by virtue of living in New York City. These were JCCs, synagogues and Federations where families had to work a little harder to find each other.

I realized, in these brief visits, how familiar were their faces, how durable the cords of Jewish vocabulary, family, comedy, melody, and fealty to history, how many strangers wanted to tell me they were related — either literally (I’m your cousin Harvey’s cousin’s sister-in-law!”), or by circumstance (“I was a year behind your father at Rutgers!”), or by experience (“Like you, I became a bat mitzvah at age 40!”).

I didn’t find myself feeling suffocated by the sameness; I was comforted by it. Awakened by it — to the warmth of kin beyond blood; comrades in habits, ethics, kvetching (complaining), anxiety, and yes, matzah.

Matzah often goes by another name: “cardboard.” Jews joke about the arduous “matzah-marathon” of Passover— the eight days during which we swear off any leavened food (chametz in Hebrew), meaning no bread, pasta, crackers, cereal, or pretzels — any dough that ferments. This embargo honors the Exodus story, when the ancient Israelites fled their Egyptian captors in such a hurry that they had no time to let their bread rise and instead, had to settle for flat pita. We eat bland matzah today to remember yesterday’s improbable deliverance from servitude.

People complain that matzah is tasteless, but for me, it’s too sweet to taste bad. By “sweet,” I mean redolent, connecting. Matzah triggers childhood, family, ritual, belonging. I belong to a tradition that requires this dry cracker for eight days, that reminds me how many generations have marked this same holiday with family around a raucous seder table every year, which insists on retelling an ancient story that resounds in every generation: a miraculous escape and how many need that same miracle today. Matzah is a very particular, powerful glue; it joins me to a story and a people.

Little by little, I started not to feel simply obligated any more; I felt animated. Challenged by the questions that the Rabbis have posed for generations: of what we owe each other, what it means not to stand idly by, whether we can find belief without miracles, whether our luck gets shaped by our behavior or by forces beyond us.

I don’t subscribe to a tribal arrogance; there’s something discomfiting about too much pride in one’s own “people.” But I have now seen the radiance of affinity, glinting in random snapshots I hadn’t known I was missing:

The sight of my synagogue congregation on a Friday night, turning in unison to the east to welcome the Sabbath, bowing left, right, and center, as if to greet an honored guest with humility and gratitude.

The sound of my son, Ben, confidently singing every word (in the shower) to “Lekh Lecha” — “Go Forth” — God’s words to Abraham when he sends him forth to build a nation. Ben knows the song because he grew up going to a Hebrew School, unlike his mother.

The conversation I overhear when my husband phones his mother, Phyllis, (in Chicago), for advice on how to re-warm the Passover brisket without drying it out.

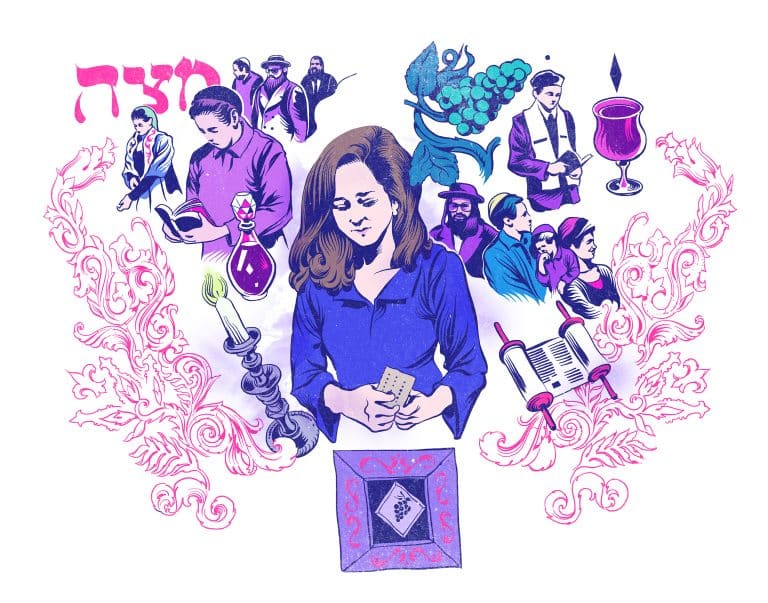

I’m suddenly sentimental about symbols — the many that tumble through the Jewish calendar. They’re just objects, I realize, which could be considered arbitrary and even sorcerous, but now they feel essential to me, talismans of endurance, intimacy, and commitment. A challah. A ram’s horn. A scroll of Torah. A yarmulke. A prayer shawl. A wedding canopy. Two candlesticks. A wine goblet. A menorah, dreidel, grogger, burnt egg, lamb shank, sprig of parsley, shaving of horseradish, bowl of salt water, bottle of Manischewitz, a broken half of matzah enfolded in a napkin.

Belonging is knowing what these things echo, stand for. It’s knowing why we pound our chests on the Day of Atonement (during a recitation of 44 sins), why we put a menorah in the window (we’re commanded to “publicize the miracle” of the Hanukkah story), why we ensure that even the poor can afford four cups of wine for a seder. Knowing is belonging, but it is also a call to activate every one of those seemingly-random symbols, every line of centuries-old liturgy, every blessing. Belonging, for me, is not passive camaraderie. There’s some kind of electrical current charging through it.

Earlier this month, BuzzFeed posted a viral story about Samantha Gross — a Boston University student studying abroad in London. “Today, something incredible happened,” Gross tweeted, going on to describe— in 19 successive tweets — how she came across a Twitter invitation from a London-based CNN reporter named James Masters:

Tonight is #Passover so if you're in London and you've got nowhere to go for Seder, get in touch. Nobody should be alone tonight.

— James Masters (@Masters_JamesD) April 10, 2017

She did as Masters suggested: replied that she was a sederless expatriate. Next thing you know, Masters and his wife were driving Gross to his parents’ home to celebrate Passover with his extended family. They welcomed her with warmth, questions, and a home-cooked meal. Gross recounts:

“While we were singing Hebrew words, engrained in both my brain and theirs, I couldn’t stop thinking of how little an ocean really means….”

How little an ocean means…between two people who belong to the same larger family. Knowing each other without knowing each other. Instant shared language (despite differing accents). “I couldn’t stop thinking about how James changed my Pesach from a meaningless abstinence from bread to a mindful week. All with a tweet.” Twenty years ago, I might have called this story saccharine; now I call it sacred.

I’m not sure any of us grows up aware of what it might mean to travel through life untethered…until someone throws us a rope and we grab on. I grabbed hold late, but was instantly pulled into a family reunion already in progress, one that welcomes latecomers. At the end of the day, this family isn’t cohesive, nor uncomplicated. What family is? And though I’m sometimes admittedly frustrated by the fissures and mishigas of the Jewish community, I’m fascinated by its shades and struggles. I’m awed by its commitment to tradition and sense of obligation. I belong now – not just by birth, but by choice. And it’s worth all the dry matzah that comes with it.