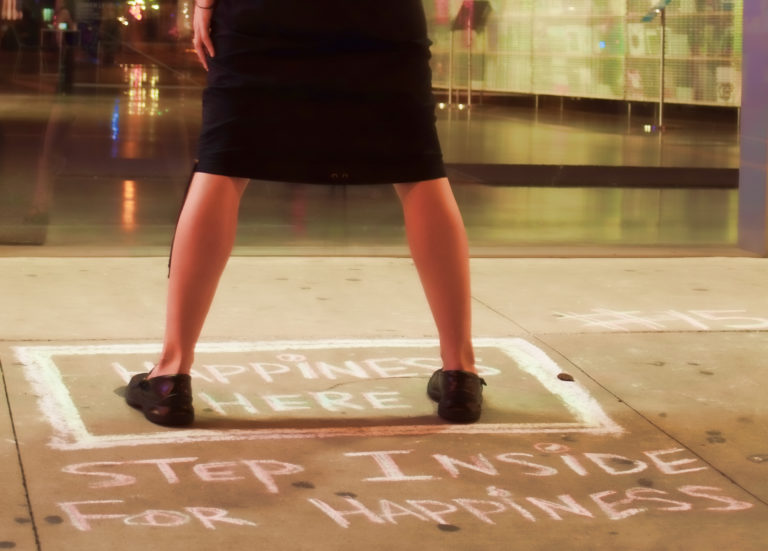

Image by Aatik Tasneem/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

The Problem with Midlife Is That We Think Life Is Over

I often hold 40 as a turning-point year in my mind. I listen to the myths and the word on the street, I hear the poems about this time, and I watch the people in my life turn 40 (and 50, 60, …80). Through it all I wonder what really goes on in the psyche and in one’s bones at that moment of life. How does one’s meaning in life and one’s purpose shift? What does this phase of life hold for – and hold up to – us?

There seems to be such a longing for the past, the energy and fervor of youth, that edge of invincible promise, when 40 seems a long, far-off place. I think these lines from Mary Oliver hold that wish:

“I want to think again of dangerous and noble things.

I want to be light and frolicsome.

I want to be improbable beautiful and afraid of nothing,

as though I had wings.”

And then I heard Tarikh Korula, a recent guest on the Reboot podcast, say: “I wonder if I am an investable entity at this point, and at this age. That has been and is an ongoing question for me.”

Am I too old for the hoodied garb of unicorn potential? Am I nothing because my chronological age doesn’t include in its wealth of experiences the cold hard cash and notoriety of a successful exit?

The problem with midlife is that we think life is over. Likewise, the problem with “failure” is when we’ve attached our self-worth to something not succeeding as we had planned. Shouldn’t we have accomplished more, or something, by this point? Lest we think midlife means the doors are closing on us, there’s a whole new set of doors opening, waiting for us to walk through. Age 52 is the life phase that you start doing your life’s work. (And Jerry, who turns 54 this year, reminds me that he considers two-year-old Reboot the best startup he’s ever worked with.) The masters among us keep going until 80-plus.

While we may feel closer to death, the opportunity at this juncture is the end of the world as we know it. That death that we are closest to is a passing of a different kind. As James Hollis notes, it’s a time in which you’re “summoned to leave behind the controlling powers of your history” and invited to move beyond the domination of those psychologies into a phase that’s more fitting of you. Noting how much our protective measures and complexes don’t fit us, Carl Jung said, “We all walk in shoes too small for us.”

Passing through middle life means becoming more and more what wants to be expressed through us. At midlife, one is honed and hammered by all the experiences that came before. Yet, the mistake is entering into midlife looking backwards at all that was done, undone, not yet done, or longing for in times past – back when it was “as though you had wings.” The parts of our life that don’t match an external standard expose a false sense of our self worth based on what we think we should have accomplished by this point, as if we’re running out of runway on our life.

Listen to this poem by Donald Justice:

“Men at Forty”

Men at forty

Learn to close softly

The doors to rooms they will not be

Coming back to.At rest on a stair landing,

They feel it

Moving beneath them now like the deck of a ship,

Though the swell is gentle.And deep in mirrors

They rediscover

The face of the boy as he practices trying

His father’s tie there in secretAnd the face of that father,

Still warm with the mystery of lather.

They are more fathers than sons themselves now.

Something is filling them, somethingThat is like the twilight sound

Of the crickets, immense,

Filling the woods at the foot of the slope

Behind their mortgaged houses.

Something, something, is filling them at this threshold. When all of a sudden there you are at 40, an adult remembering all that you’ve done, the kid that you were, the more-like-a-parent-now that you are, looking out beyond all that you’ve built/bought into, the immensity of what may come, and into what’s next.

In the podcast Jerry and Tarikh talk about Parker Palmer’s “tragic gap” — that gap between where we are and what we see what could be in the world. But perhaps the tragic gap closer our psyche is this chance at midlife when we turn away from the rearview and look ahead into that transitional space where old psychologies die and new paths emerge. It’s a time for us to come more into alignment with ourselves and walk in deeper integrity in our relationship with self and our work in the world.

An old poem written by Dale Wimbrow back in 1934 about integrity and honesty that I first heard read by my favorite horseman, Ray Hunt, at one one of his colt starting clinics over 20 years ago. It reminds me about what I imagine happens at midlife, as if the man in Donald Justice’s poem is also contemplating something like this behind his mortgaged house. (Note that the word pelf means wealth.)

“The Guy in the Glass”

When you get what you want in your struggle for pelf,

And the world makes you King for a day,

Then go to the mirror and look at yourself,

And see what that guy has to say.For it isn’t your Father, or Mother, or Wife,

Who judgement upon you must pass.

The feller whose verdict counts most in your life

Is the guy staring back from the glass.He’s the feller to please, never mind all the rest,

For he’s with you clear up to the end,

And you’ve passed your most dangerous, difficult test

If the guy in the glass is your friend.You may be like Jack Horner and “chisel” a plum,

And think you’re a wonderful guy,

But the man in the glass says you’re only a bum

If you can’t look him straight in the eye.You can fool the whole world down the pathway of years,

And get pats on the back as you pass,

But your final reward will be heartaches and tears

If you’ve cheated the guy in the glass.

James Hollis writes in What Matters Most: Living a More Considered Life that “We are not here to fit in, be well balanced, or provide exempla for others. We are here to be eccentric, different, perhaps strange, perhaps merely to add our small piece, our little clunky, chunky selves, to the great mosaic of being. As the gods intended, we are here to become more and more ourselves.”

Until we’re masters at it.