Image by Library of Congress.

Allied in Music: One Man’s Dream of Unity

Toward the end of four years abroad teaching music and English in Kyoto, Japan, I read an editorial in the International Herald Tribune by the scholar Richard Sennett with the provocative title “America Is Better Off Without a ‘National Identity.’” In it Dr. Sennett criticized a plan to hold “‘town meetings’ aimed at overcoming ethnic rivalries” and described “the very notion” of an “American identity” as a “sweeping stereotype.” While I objected to the assertion made by Dr. Sennett’s title I wasn’t fully confident about how to respond to its challenge in my own mind. It seemed to me the question of whether or not there was such a thing as an American identity — something intangible we hold in common — was an issue long past the point of debating. Yet what was it that we shared?

My desire to better understand American culture eventually led me to a graduate program in musicology at the University of Pittsburgh. There I studied how commercial radio had transformed the beliefs of members of a campaign to “make America musical” in the early twentieth century. They promoted what they called good music — now generally known as “classical music” — and viewed many other musical styles as bad or cheap.

The key to the dissertation I eventually wrote was an essay by Charles Seeger, father of the late folk singer Pete Seeger, titled “Music and Class Structure in the United States.” It described the interaction between different types of American music over time and the democratizing role commercial forces had played.

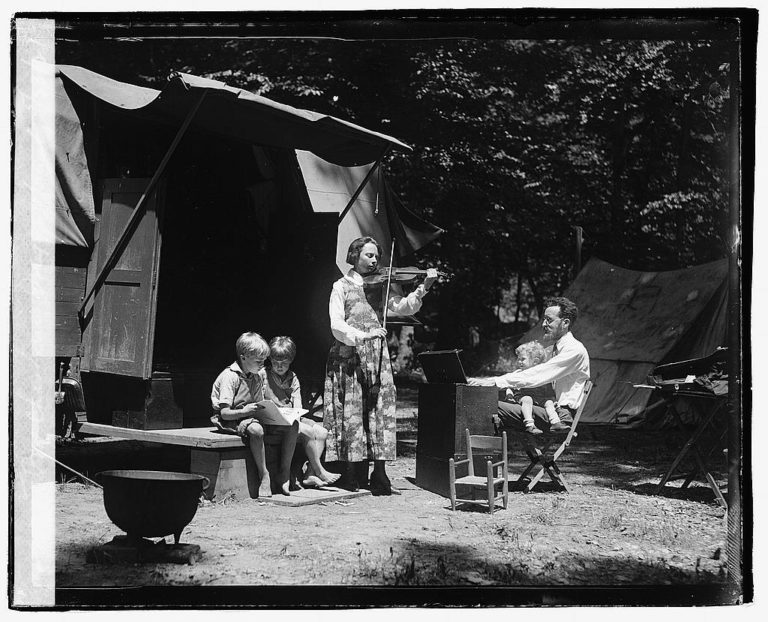

In late 1920 Mr. Seeger and his first wife Constance, a violinist, set out with their three sons, including young Peter, on a trip to bring good music to the people, towing a trailer equipped with a pump organ behind a Model T Ford. Together they gave recitals and small concerts, sometimes for money and sometimes for free. While in North Carolina the roads became impassable and they parked their trailer for the winter in woods owned by a family named MacDonald. During that season the Seegers played classical music for their hosts and in turn were treated by the MacDonalds and their neighbors to music on banjos and fiddles.

Prior to this Mr. Seeger thought folk music “didn’t exist…except in the minds of a few very old people, who would die shortly and then there wouldn’t be any,” and this encounter seems to have had a profound effect. These people had their own music, and it was precious to them. They didn’t need his.

Before technology made it effortlessly available, music had to be created in order to be heard and so music was a natural way for people to come together. Just as the MacDonalds came together with their neighbors and with the Seegers. While we still can come together to enjoy music today, we don’t need to and so mostly we don’t. For most, music is simply entertainment encountered in solitude.

Despite widespread gains in public music education, music is like a language that must be used actively in order to maintain the ability to read and write. The rise of individual music listening has led to a decline in the average American’s level of musical ability and so diminished their access to music’s potential.

We now need music’s ability to bring people together more than ever. Music can serve as an important tool as our society negotiates unprecedented changes. It can unlock and open our hearts, empowering individuals while also enabling the diverse elements of American society to speak to each other and so build a sense of commonality. One of our greatest challenges will be to view the Janus-like reality of our ever-increasing diversity primarily as a resource and an opportunity. The source of American renewal since its inception, diversity, is a tremendous gift that we share.

Music can contribute to positive social change if more people encounter music as it is created — either as participant or audience. It promotes individual growth and mindfulness while providing channels of communication between divergent social, cultural, political, economic, and generational groups. It can enable us to communicate our individuality while forging a more perfect union by creating moments that bridge the divides separating myriad competing groups. At times, music brings together people who otherwise might never encounter each other.

That is why I decided to begin creating a new organization, The Musical Alliance of the United States, a namesake of an organization founded by John C. Freund, founder and editor of Musical America. In 1918 he called for an alliance to organize “all workers in the field [of music], from the man at the bench in a piano factory to the conductor of the great symphony.”

The alliance seeks to unite all existing groups and individuals who support musical performance through collective affirmation of the values they already share, to infuse their work with a renewed sense of music’s potential. It aims to unite the supporters of various types of music — professionals and amateurs, performers and concert-goers, symphony orchestras and community choruses, music teachers and their students — anyone who believes that music can bring people together. In this way music might contribute to the ongoing effort to meld a big, teeming whole out of America’s many parts. E pluribus unum.

The concept of the new alliance is simple but ambitious. As I currently envision it, a complex website could connect the alliance’s members and allow them to form groups and subgroups and facilitate discussions about collective needs and concerns. The alliance would seek to generate mutual support for existing efforts and avoid putting itself or any organization it helps create in competition with existing groups. The Musical Alliance of the United States would begin with the formation of a chapter in the Washington-Baltimore area and expand nationally within a few years.

Although the primary role of the alliance would not be creating new musical enterprises, its members could identify unmet needs and opportunities and facilitate solutions. An early project of this type could be the creation of a new youth music program in Washington modeled after the highly successful Venezuelan program, El Sistema, which could be spun off as an independent group.

Science is revealing the unique role of music in human thought. As cognitive researcher Daniel J. Levitan writes:

“Music is not simply a distraction or a pastime, but a core element of our identity as a species, an activity that paved the way for more complex behaviors such as language, large-scale cooperative undertakings, and the passing down of important information from one generation to the next.”

If we act together we can align the power of music so it supports positive social change, helps unlock the potential inherent in our diversity, and contributes to the building of the beloved community to which we aspire.