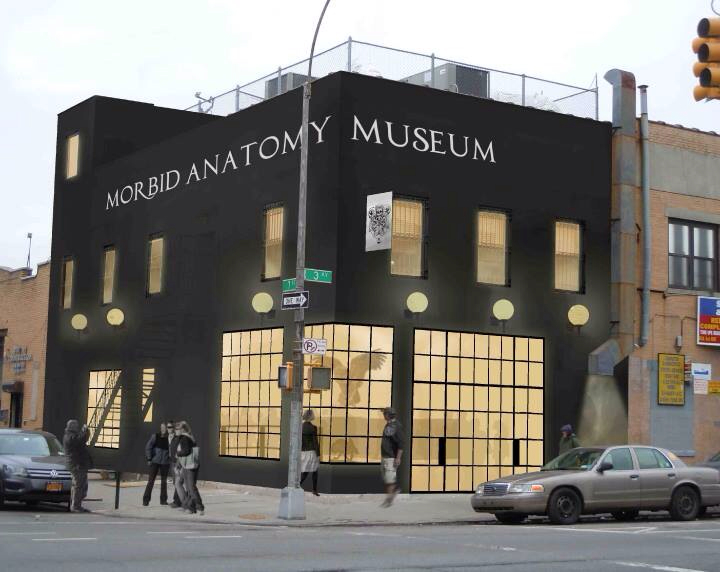

Image by Tonya Hurley.

Can a Museum of the Macabre Help You Deal with Death?

The Morbid Anatomy Museum recently opened its doors in the rapidly gentrifying Gowanus section of Brooklyn to reviews of “a fascinating journey into the dark side” that “adds a little death to your day off.” But can a museum dedicated to mortality help open the taboos around death in our culture?

Housed in a renovated former nightclub, the modish building — aptly painted black — contains a full-service coffee bar and gift shop, an exhibition gallery, as well as a library and events space for book parties, films, and even singles nights.

Beyond the collection of books and the esoterica — including taxidermy of the two-headed chick and the 3-D wax imprint of syphilis of the face — I found much to mull over in the temporary exhibition, “The Art of Mourning.” In the 1800s, life expectancy in America was short. The dead were often laid out for friends and family to view in home parlors and mourning objects and artwork commemorated the deceased.

What kinds of objects? Memorial hairwork, for starters. Because human hair will last for centuries and represents a person’s individuality, hair was used in the Victorian era to create keepsakes. A small glass dome covers one elaborate graveyard scene, fashioned out of human locks.

Across the room is a collection of 30 photographs and portraits of the dead, meant as remembrances for the living. Many of the images depict children dressed in their finest, lying in a carriage, in a father’s arms, or in a coffin holding a rosary.

I spoke to Joanna Ebenstein, the museum’s creative director, about how the general public might perceive such an exhibit. “People think it’s morbid to talk about death and dying,” she said. “But I feel that thinking that way is morbid in itself.” I couldn’t agree more. The dizzying number of exhibits, lectures, classes, and other events on the calendar are aimed to bring the modern-day curious square into the face of death. Where that conversation takes us is up to us, the participant, to decide.

Leaving the museum, I noticed something in front of the auto repair shop next door that made what I had just seen come together — a lovingly tended altar with flowers, votive candles, and a picture of a young man who looked like he had died far, far too young.

Share your reflection