Image by Deveion Acker/Flickr, Attribution.

What Am I For?

What am I for? I’ve been asking this question of myself a lot lately. The wording of it was planted in my subconscious by Wendell Berry, who has a beautiful book called What Are People For? In it, he writes:

“The shoddy work of despair, the pointless work of pride, equally betray Creation. They are wastes of life.”

I spent much of my 20s on what most generously could be described as building a body of work, a professional identity, a sense of my own place in the world. It was an ambitious, angst-y, tumultuous time, a time of knocking my head against a lot of walls and figuring out how to open doors and windows with great difficulty. In Berry’s frame, there was a lot of pride involved — some of it probably very pointless, some of it, I would argue, akin to a basic human striving to be seen. I craved to see myself and have others see me. I was quite desperate about it at times. I worked at that.

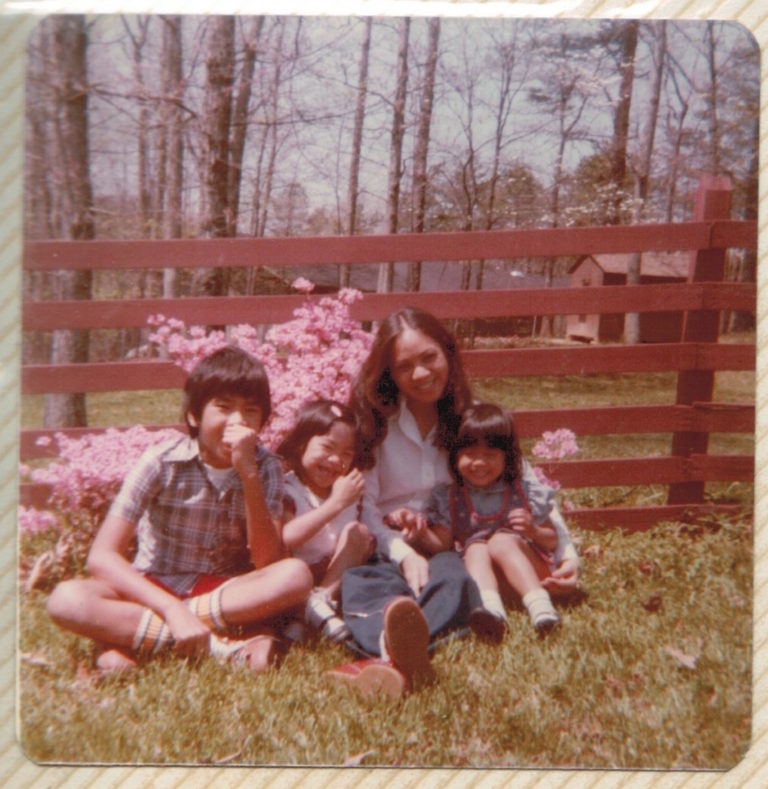

My 30s have evolved differently. I’ve been making and raising babies, so that has deeply shaped these years. I haven’t had a lot of cause to ask “What am I for?”

Every four hours or so, I’ve nursed a baby — an embodied and ritualistic answer: I’m for milk. I’m for comfort. I’m for cognitive development. I’m for these girls. Just as war is a force that gives us meaning, I believe parenting, and especially mothering in the early days, is a force that gives us meaning. The meaning is inescapable. It’s exhausting but, in many ways, a nice respite from some of the existential questions that otherwise inevitably plague an awakened soul.

But as my girls have been getting older (my eldest is three and a half, definitively and miraculously her own person), this question has started showing up in my subconscious more and more. It whispers sometimes. Shouts at others. This week, it’s shouting. What am I for?

I feel, as Berry wrote, that I am too old for pride. It feels so juvenile to make decisions about how to use my time based on pride. I’ve already learned that it doesn’t lead me to the most rewarding places, but rather a sort of hollow accomplishment. Making decisions based on pride leads me to have great cocktail party anecdotes.

Alternately, making decisions based on self-knowledge — my actual gifts, my “deep gladness” in the words of Frederick Buechner, my “optimal discomfort” in the words of Jean Piaget — lead me to feel astonished and grateful. I don’t even need to tell the story. I feel lucky to be of use, to be witnessed, to admire myself. I feel not that I have made something, but that something has made me. These kinds of decisions often don’t even feel like decisions. They feel like surrender. “Let me be a vessel,” I say to the universe, and when I’m doing the right work it’s a forgone conclusion. When I’m working for pride or security or status, I say, “Let me be a vessel,” and I can actually hear the universe’s radio silence. It’s a crushing static.

In my late 30s, I don’t have time for pride. I feel painfully aware of how short life is. I birthed my children alongside an excruciating and ever-present awareness of mortality. How could I possibly waste my time here chasing good cocktail party stories? How can I justify that static, no matter what the material rewards?

So what am I for? What is the through line to this incredibly beautiful, brutally finite life?

I don’t know. (I feel like I know almost nothing lately.) But I know this: being lost is productive. I’m probably far too sure of what I’m for most of the time, missing all kinds of wonderful twists and turns that would delight me and serve the world because I am too busy plowing straight ahead with my blinders on. For now, I’m going to tolerate the floating feeling that accompanies moments like this of not knowing, buoyed by a hope that there is something wiser beyond the horizon of my understanding.