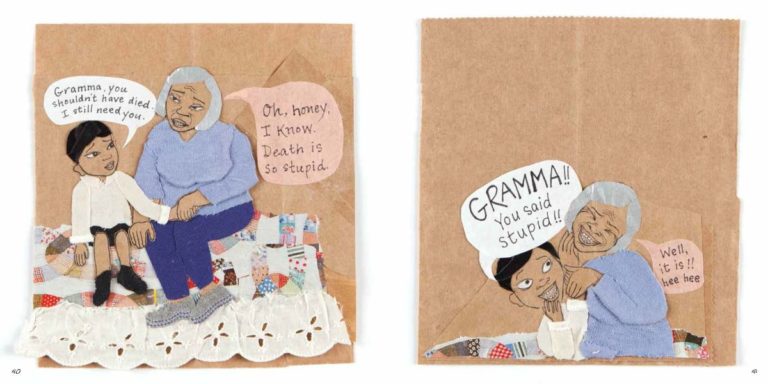

Image by Anastasia Higginbotham/The Feminist Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Death Is Stupid, and Other Lessons Children Teach Us About the Inevitable End

Death is stupid. Or so says Anastasia Higginbotham, the author and illustrator of a new book for kids with that title. She goes on:

Every life comes to an end. Dying is not a punishment. But it mostly doesn’t feel fair.

It’s a beautiful assemblage of a book — as if Romare Bearden himself rose from the dead and created a sequel to Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. Thumbing through it, I was once again reminded of how dumb we are at a grief in this country, generally speaking, and how much we have to learn from even the most basic instincts of children.

Higginbotham, for example, warns her tiny readers:

Beware of the lies.

You know, the ones we tell that we think somehow kids won’t interrogate even though we have every shred of evidence that they are intuitive sleuths from day frickin’ one. My two-year-old daughter Maya found a dead bird on the beach and became completely transfixed by it. She squatted nearby, staring, for minute after minute after minute and demanded to know what happened. When her Oma (grandmother) and I stumbled over our words, she wouldn’t move on.

“Some people think animals have spirits that can move outside of their bodies,” Oma tried to explain. “Maybe he’s in a better place.”

“Like over there?” Maya asked, pointing to the tall grasses just north of where we were huddled around the lifeless bird. She looked unconvinced. If there was a spirit, where exactly was Oma purporting it might be hanging out? She wanted answers, not abstraction. She asked to take a picture of the dead bird with my iPhone. I let her.

I could tell it was part of her process for working out what this was all about.

Higginbotham, perhaps having experienced the inadequacies of adult explainers like Oma and me, advises her readers:

If you have questions for the one who died, ask them in your imagination or right out loud.

My maternal grandfather, Cork, he was called, died while my mother was pregnant with me. But he lived on in the epic stories I heard around the Thanksgiving dinner table. He played football for the University of Nebraska and twisted the glass necks clean off of beer bottles when he didn’t realize they required an opener. He was a traveling salesman and once had my grandmother sew a collared shirt with Velcro along the seams so he could dramatically rip it off as he promised a potential client: “We’ll give you the shirts off of our backs!”

I used to pray to him while lying in my little canopy bed at night. No one told me to do it. I don’t think I even mentioned it to my mom, who missed him terribly. It was just an instinct.

As it turns out, it is a healthy one. In researcher George Bonnano’s The Other Side of Sadness, he finds that the people who weather the erratic ups and downs of grief the most gracefully are those that don’t shy away from having an ongoing relationship with the dead. Ask them your questions. Treasure the things they left behind. Look for them in peculiar places.

Because while death, the ultimate end, is inevitable, remembering lasts. That’s what Higginbotham says.

I’m so grateful she’s right. In the case of my grandfather, a man I never even knew, the stories have made him eternal. Maya was born on his birthday. Pretty soon we will get a big white piece of paper out and put it on the kitchen table and draw a likely unwieldy and imbalanced family tree and I’ll show her the branches that reach up to Cork and tell her about the tear-away shirt and the beer necks and we’ll laugh, and maybe I’ll even tell her how robbed I know Oma feels of getting to spend more time with him, and he will still be dead, but very much alive too, and that will make it all far less stupid.

“The other place” that spirits go, it turns out, is into the creative power of our own hearts and minds, the people we conjure up with our stories, the connections we weave which transcend our corporeal limitations and tragic losses. This is what kids already know. If only we’d let them, let ourselves, keep knowing it.