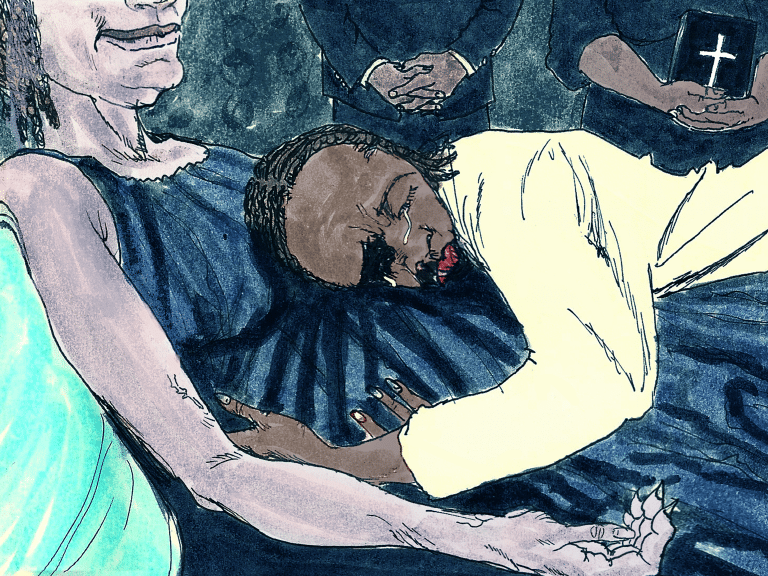

Image by Vin Ganapathy, © All Rights Reserved.

A Voice from Heaven

I was talking to my mother when she died. She was visibly slipping away. She was no longer eating or drinking. Her body was cold. Her eyes were glazed as she drifted in and out of consciousness.

“I love you,” I told her over and over, as I held her hand, kissed her face, stroked her hair.“You’re a wonderful mother.”

Hearing, they say, is one of the last senses to go. My mother smiled.

I tearfully asked her, “Mommy, can you see heaven?”

She smiled again.

Then she was gone.

At her wake and funeral service, I was too scared to tell the story of how Mom had smiled her biggest smile in months when she heard the word heaven. I was worried people would think I’d made it up. Even though I had witnesses. There had been others in the room with me — my mother-in-law, the social worker, and the hospice nurse — and they had all confirmed that yes, my mother had smiled broadly right before taking her last breath. I was still worried that no one would believe me.

Instead I told the story to the young minister, a childhood friend, my brothers, and I asked to say the homily at my mother’s wake. This young minister had known my mother his whole life. He constructed his sermon around the story. He titled his sermon “Mother Danticat’s Smile.”

“You could never walk away from an encounter with Mother Danticat without experiencing her smile,” he said.

The young minister’s sermon made me think anew about this idea of the dead smiling down on us from heaven. My mother made a powerful case for it herself with that final smile. The young minister, though, avoided the cliché. We were blessed, he said, to have enjoyed that smile while Mom was still with us.

When my mother was sick with stage-4 ovarian cancer, we had nightly devotions, just the two of us. She was visiting me from New York when she was diagnosed and had decided to stay for the treatment we hoped would gain her an undetermined amount of time. My mother was a devout Evangelical Christian and a member of a congregation of close to a thousand people in New York. In Miami, I visited many churches, but the one I attended most often met behind a grocery store and consisted of three or four families. Mom was missing the most expressive elements of her faith, the hours of sing-along worship, Bible study, and other group meetings. I tried to fill the gap.

Every night after everyone else had gone to bed, we would sing a hymn, recite or read a verse, pray, recite the Lord’s Prayer, read another verse, then go to sleep. Mom had some favorites, Psalm 23 and the Beatitudes among them. The Beatitudes must have offered an extra dose of consolation. They were assurances, promises, which were about to be fulfilled, something I imagine she’d pierce the veil of heaven to tell me about now, if she could. In the Beatitudes, there was comfort both for her (“Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted”). She still had time to purify her heart. I had a lifetime to mourn.

Most of the time though Mom couldn’t remember what verse she had in mind. Sometimes she’d recall a word or two and I’d go fishing in an online concordance for them.

“Syèl la,” she’d say in Haitian Creole, signaling that the verse was somehow related to heaven.

When dozens of possible choices would appear, she’d ask me to pick the one closest to the top, or one we hadn’t yet read. I would use different concordances, so the verses wouldn’t always appear in the same order. This is how I came across Revelation 14:13 one night.

In my mother’s French Bible, it read:

“Et j’entendis du ciel une voix qui disait: Ecris: Heureux dès a présent les morts qui meurent dans le Seigneur!”

Then I heard a voice from heaven say, “Write this: Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord.”

I stopped reading after the equivalent of on.

This verse was so well suited to both my profession and my mother’s circumstances that it seemed indeed like a command from heaven, not just to the Apostle John, the reported author of the Revelation, but also to me. Write, it said, though, as my mother’s condition worsened, I was too grief stricken to even sign my name. Write not just about living but also about dying.

I have been writing about death for as long as I’ve been writing. The mother of the narrator of my first novel stabs herself seventeen times while she’s pregnant. Hundreds of people drown on the high seas in my second book. My third book recounts a little-known Caribbean massacre in which thousands of people are methodically killed. While most of my work is based on actual events, I chose those subjects because I was so afraid of death that I wanted to desensitize myself to it. Many Haitian folktales begin with a death, or presume that it has already happened. Often it is the death of a mother. Most of these stories, like my mother’s favorite Bible stories, offer the hope of an afterlife. Still, death remains what I most fear for the people I love, and what I most fear they’ll have to not just endure but define and redefine for themselves after I’m gone.

“The death of a beloved is an amputation,” C.S. Lewis writes in A Grief Observed.

That amputation has always terrified me.

“No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear,” Lewis wrote.

No one told me either.

I started reading C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed when my mother was hospitalized for the last time and was preparing for home hospice. One never stops hoping for a miracle, but as my mother’s body whittled away, it appeared less and less likely. Even the focus of my mother’s prayers shifted. Rather than praying for healing, she started lingering on the part of the Lord’s Prayer that says, “Thy will be done.” She would repeat this line several times, as though it was now the only necessary prayer, the only one that mattered.

Ten years before, my father had made the same transition as he was dying from pulmonary fibrosis. His suffering — he was constantly coughing and out of breath — was a lot more visible than my mother’s. No one had to ask him to rate his level of agony. It was always writ large on his skeletal face. His “Thy will be done” also became a plea for death.

“I didn’t put myself on this earth and I can’t take myself out,” he’d say. “But if I could . . .”

He never allowed himself to finish the thought, but we knew he wanted out.

Mom wanted out, too, and started to withdraw. She stopped watching television and talking on the phone and no longer wanted me to read the Bible to her. It was as if the biblical conversation had now shifted to inside her head, becoming a secret dialogue from which I was suddenly barred. Instead she listened to sermons live-streamed on the internet by a young pastor friend she’d been following since he was a teenage preacher in New York.

With my mother pulling back from our devotions, I tried to find solace in the verses and half verses she’d led me to. Reading the Bible, I realized, was one more thing I would have to do without her after she was gone. So, I started reading A Grief Observed as a companion to my mother’s Bible verses. I read it in the waiting rooms of diagnostic centers and in hospital rooms while she slept. Someone had given me a copy after my father died. My grief was too fresh to fully embrace it then. So I skimmed through it and put it away. Still, a few phrases stayed with me. The sentence about grief feeling like an amputation rang true. So did the one about fear, a kind of all-encompassing terror that would creep over me for months after both my parents died.

Like Mom, Lewis’s wife — he calls her H. in the book — dies from cancer. “One never meets just Cancer, or War, or Unhappiness (or Happiness),” he writes. “One only meets each hour or moment that comes.”

Each moment with my mother brought a deeper understanding that she was slipping away from me, and that heaven, “Syèl la,” was growing nearer and nearer. My mother had fully surrendered, but I was still flailing. Heaven did not seem like such a great place if everyone who was there had been plucked from somebody’s arms. They might be blessed, those who are dead in the Lord, but what of the wretched lot of us, those they’ve left behind?

Lewis seemed to have had a similar thought:

“His [God’s] ideas of good are so very different from ours, what He calls Heaven might well be what we should call Hell…”

He asks his dying wife to come to him on his deathbed.

“Heaven would have a job to hold me,” she tells him, “and as for Hell, I’d break it into bits.”

Reading the Bible out of context is discouraged by all the ministers I know, but it was the only way my mother and I could read it together in the end. We only had time to zigzag through it to find what Mom wanted and needed to hear. The way we were reading it, though, led us to many comforting fragments, pockets of isolated thought, islands of ideas that, completely stripped of their context, perfectly suited us.

The Revelation, with its fiery prophecies of famines, earthquakes, plagues, and wars, is a pretty frightening book. Yet it is the one book in the Bible I kept returning to in the early days after my mother died. This felt odd, even to me, because it’s also the one book I would have most hesitated to read to my mother during her last days.

The Revelation’s vision of last days, all our last days, is so horrifying that it would have burdened, rather than lightened, my mother’s heart.

Take, for example, the beginning of Chapter 13.

“Then I saw a beast rising up out of the sea. It had seven heads and ten horns, with ten crowns on its horns. And written on each head were names that blasphemed God. This beast looked like a leopard, but it had the feet of a bear and the mouth of a lion! And the dragon gave the beast his own power and throne and great authority.” (Rev. 13:1-2)

Surprisingly, I found myself relishing the descriptive and evocative, if sometimes chilling, imagery of that book, the urgent stream-of-consciousness narrative, the suspenseful rollout of horrors, all of which made it seem as though my mother was lucky to have departed from a place for which this was, as she believed, a possible future.

The framing of the narrative itself seemed extravagant, to say the least. It was every writer’s nightmare, being directed to jot down the orders of an enraged muse and told not to change a single commanding word. Still, nestled in the midst of all that fire and brimstone was my mother’s little glacier, her own oasis, her vision of heaven.

There are other reassuring fragments from the Revelation that I now wish I’d had a chance to read to my mother, places where, after the torment and terrible suffering, everything suddenly becomes peaceful, idyllic.

In the final chapters of the Revelation, we catch a glimpse of a brand-new heaven and a new earth, where there is “no more death or mourning or crying or pain,” where Eden is restored with new life and rivers flow clear as crystal, and crops bear abundant fruit and both people and nations are healed.

We are promised that:

“There will be no more night. They will not need the light of a lamp or the light of the sun, for the Lord God will give them light. And they will reign for ever and ever.” (Rev. 22:5)

Maybe this is the heaven my mother wanted me to find for her as we crisscrossed the Bible. Maybe this was the heaven she was seeing when she smiled at me before taking her last breath, the type of heaven for which you have to surrender everything else, the kind of heaven that even if you could shatter the universe to bits, you would never choose to turn your back on, to return to your old life.

This essay originally appeared in The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, now available in paperback, and is reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster and the author.