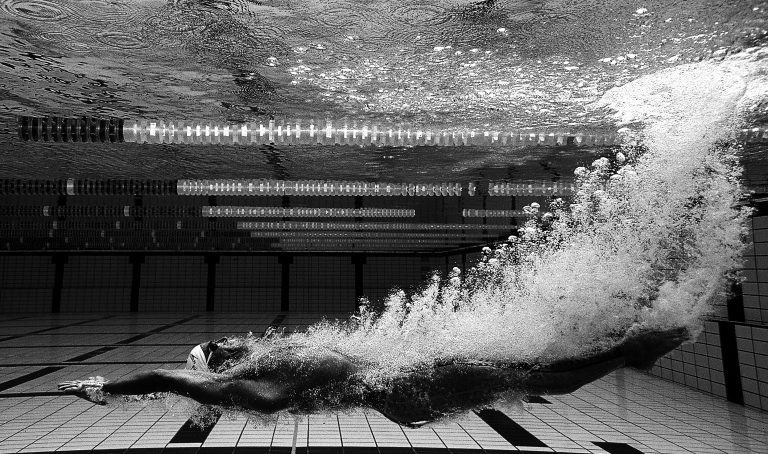

Image by Adam Pretty/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

The Good Thief

There was a time in my life when competitive swimming was religion. By high school I was in the pool up to nine times a week and ten thousand yards a day. My coach had recently sent an athlete to Olympic Trials, so his regimen was proven. The only thing that remained to be seen was the commitment of his swimmers.

Much of swimming is a battle for air. In freestyle and butterfly, raising the head wastes motion and costs time, so at an early age swimmers begin “hypoxic” training. An eight-year-old can finish a one-lap race without breathing. Young teenagers can swim two laps this way. At their peak, some swimmers can hold off the blackout point long enough to finish three laps. This is central to the culture of the sport. A competitor who loses a close race because he breathed too often, or came up for air too soon after a turn, is viewed as undisciplined. Young swimmers learn that surrendering to the painful, fundamental urge for oxygen is shortsighted and destructive. Self-denial is essential to success.

My specialty was the marathon of high school swimming, the five-hundred-yard freestyle. The 500 free is a race so long — twenty laps — that athletes aren’t expected to keep track of their own progress. Teammates mark the lap count for them by dunking numerical boards into the water as they approach the wall for a turn. Training for the 500 is miserable. In the years before I had entered the sport, the orthodoxy of distance swimming had changed. On the theory that athletes could profit from technique training as much as from brute yardage, coaches had underprepared a generation of American distance swimmers, who proved unable to dig as deep or suffer as much. Now the coaches were repenting. Our workouts were ever more grueling.

Today I ask myself why I did it. Why, for the last two years of high school, I came home in the evening from swim practice, bolted my dinner, and hurried to finish my homework by half past ten, knowing that I was unable to survive on fewer than five and a half hours of sleep, and that I would miss my swimming carpool if I woke later than 4:00 a.m. Why, on Friday nights, after our high school team had competed in a weekly meet, and the upperclassmen had gone out together to celebrate, I allowed my pleasure to be fringed with dread of the next morning, when we distance swimmers would be sequestered in our own lane with our own workout for the longest and most hated practice of the week.

One reason I did it is that swimming had changed me. I’d begun the sport as an asthmatic eight-year-old, surviving allergy season on a careful program of Choledyl syrup, albuterol inhalers, and weekly injections. I was not allowed outside for recess in the spring, and I wore a breathing mask at the bus stop when the pollen count was high. Yet by the time I entered high school, the yearly breathing tests with the allergist revealed an almost miraculous change. My lung strength and capacity were far above average. I could hold my breath easily for two minutes. In addition, swimming had stretched me. I was almost six foot two, with an arm span nearly triple the waist measurement of my racing suit. My competition times were in free fall, and the messianic possibility that crosses every athlete’s mind at least once had finally settled over mine: Could I be the one?

The other reason I swam was Tom Dolan, who led the distance lane on Saturday mornings. Tom was six foot six and cadaverously thin. Shambling across the pool deck in his hooded swimming parka, he was a vision of death. We couldn’t have imagined this at the time, but in the 500 free he would go on to win three national championships in college and set an American record. Later he would win gold at the Atlanta Olympics, repeat this at Sydney, and become famous not just as the world record holder in one of our most grueling events but as the severe asthmatic who had done so with only 20 percent of his lung capacity.

On Saturday mornings, Tom was our lead dog. In the distance lane, we drafted off him. There are two standard pool lengths in competitive swimming — twenty-five-yard short course and Olympic fifty-meter long course — and when the movable bulkhead of the Saturday pool was dragged back to convert it from one to the other, the laps suddenly felt endless. The distance between walls made the water flat, dead, because currents dissipated rather than reflected, so that my body would feel becalmed. Yet Tom could force a wedge even through an Olympic-size pool. The water simply parted for him. After a few months of training in his lane, I felt myself on the cusp of finding out what I was capable of.

Early the following spring, I qualified to swim the 500 free in the finals of the high school state championships. For the first time, in that heat, I would compete side by side against Tom. Since I was a junior and he was a senior, this would be my only chance to see how we measured up before he graduated. My strategy was simple. I had learned to use his draft better than any other competitor. I would stay with him until the final burst. Then we would see what I was made of.

That night, Tom taught all of us a lesson. On his way to shattering the meet record, he finished twenty lengths of the pool before the rest of us could finish eighteen. In the language of swimming, Tom lapped us. The only part of it I remember clearly is that Tom was still in the water, waiting to shake our hands, when the rest of us finished. As I swam toward that final wall, the ghostly cross of his body came into focus, legs dangling in exhaustion, arms stretched out along the gutter to support them. He was going places the rest of us couldn’t follow, but one final time, he waited for us.

I lasted two or three months on my college team before the lesson took full root: I was not the one. I stayed on the varsity squad just long enough to attend one particular team meeting, overseen by the head coach in one of the training rooms by the pool, that turned out to be a proselytizing session by a campus Christian group, Athletes in Action. At the end of it, we were asked to sign up for Bible study. We freshmen, in the spirit of compliance, agreed.

I had arrived at Princeton a confident atheist. Now, twice a week, I was visited by a former college wrestler named Brian, who came to my dorm room with Bible in hand to discuss scripture in an Evangelical framework, teasing the sense from passages in Paul and then recommending books by C.S. Lewis that would help me understand the general thrust. All of this was odious in a way I couldn’t quite put my finger on. To be mistaken for a person who would commit so deeply to something so dubious, on the basis of conversations so superficial, seemed patronizing, except that it was obviously the honest mistake of someone who happened to be such a person himself. Out of fellowship and charity, Brian was offering to me what had meant so much to him. He was capable of looking at me and seeing a younger version of himself.

This was my first taste of the loss. My demotion from student-athlete to mere student came with a great sense of abandonment. So many years, so much struggle and sacrifice: How could it now be invisible? What I had done in the swimming pool, year after year, was surely one of the most important testaments I had written about myself, and, even if it had ended, it remained a guidepost to more invisible, more abiding qualities in me. I felt angry and afraid that a fellow athlete — who must have understood what it meant to be relentless and striving, never satisfied, intent on the hard way — could think I would be persuaded by a hasty reading of a few haphazard Bible verses. I felt compelled to show him his mistake.

The great discovery of my early college career, and the one that ultimately absorbed the shock waves of the loss of swimming, was that I could redirect all those hours from the pool to the library, with better results and more pleasure. In the first week of term, one of my courses assigned the Iliad, the Odyssey, and assorted poems by Sappho. It sent a ripple of disbelief and terror through most of the class to be assigned one thousand pages of reading in seven days. It was then that I discovered some of my fellow freshmen felt otherwise. They had spent high school learning Latin and even Greek. One was finishing his translation of the Aeneid. These students, far from being panicked by the reading list, proceeded to bring little green Loeb editions to our seminars in order to discuss points of translation. Here was something new and wonderful: not just the experience of classical literature, and of reading critically, but of finding myself grossly behind at something I was quickly deciding I loved. Within a few weeks, that same class turned its sights toward the Bible.

The first and only gospel I read with Brian was the Gospel of Matthew. It soon became clear that we were reading it for the fifth chapter, the Sermon on the Mount, which contains the quintessence of Jesus’s moral teaching. Brian must have thought even the most heartless atheist couldn’t object to that. By now, though, I had an agenda of my own.

The Gospel of Matthew is a thorny book. Whoever wrote it — most scholars today would say it can’t have been the disciple Matthew, for whom it is named — was influenced by a private trauma: the author seems to have lived during a tumultuous period of the early Church when the Christian movement had reached a crisis point. Jews were not converting in great numbers, and, instead, the movement was being expelled from the synagogues it had formerly called home. Jews who believed in Jesus — including the gospel’s author — were being forced to acknowledge their separateness, their homelessness, and their countrymen’s refusal to join them. A close comparison of the Gospels reveals that Matthew repeatedly compares Jesus to the Jewish hero Moses: no other gospel claims that, when Jesus was an infant, a king tried to kill him by ordering the extermination of all young children in the vicinity. (This echoes the story of Moses’s birth.) No other gospel rearranges the order of Jesus’s miracles so that ten of them can occur in a row. (This echoes the story of Moses and the ten plagues.) It seems the gospel was written for an audience of Jewish Christians, to reassure them of Jesus’s triumphant place in the Jewish tradition embodied in Moses.

But this background also gives Matthew its dark side. A deep vein of bitterness and frustration runs through the gospel, as if its author was wounded by other Jews’ refusal to consider Jesus the Messiah. Thus only in Matthew’s gospel does Jesus compare himself to a stone that is rejected by builders, even though it later proves to be the cornerstone. In no other gospel does Jesus say that the Jewish Pharisees who reject his ministry are a “brood of vipers” who cannot “flee from the judgment of hell.” The closer Jesus comes to his death in the story, the more the author’s feelings rise to the surface. Finally, at 27:25, Matthew delivers the most chilling line in any gospel. The Jewish crowd, condemning Jesus to death, cries out, “His blood be upon us and upon our children.”

Here, beneath Jesus’s message of love, was a private record of injury and anger, the ugly reality of human nature. Not even an evangelist, the best of Christians, could turn the other cheek to his experience of abandonment and failure. I recoiled. Perhaps I detected the reflection of my own experience, my own injury. If so, the resemblance only disgusted me. This was the last part of the Bible I read with Brian. After our discussion that day, I called off our meetings. Not for many years would I so much as pretend to read any part of the Good Book with an open heart.

Ten years later, almost to the day, my wife and I were married. The ceremony took place on a beach rather than in a church. I hadn’t swum a lap since quitting the college team, but something about the ocean beckoned. The old religion. But no other: not a verse of scripture was read.

Our son was born nine months later. The night we brought him home, I nervously placed him in my lap and began reading aloud from the Odyssey. A father-son story, and the beginning of a promise: to share with him the touchstones of my life. I could no longer fathom how I’d once devoured all of Homer in a week; now it took a month of nightly reading for us to bring Odysseus home to Ithaca. In the year that followed we read seven plays by Shakespeare and two novels by Dickens. By then I had discovered how deeply this promise mattered to me. How doggedly I would honor it even as other good intentions gradually slipped out of keep.

It was my wife who decided the time had come for swimming lessons. The class at the rec center was for parents to stand in the shallow end and raise and lower their infants into the water. This was silly, but I agreed. In parenting a baby, as in training for a distance race, the sets and intervals are really just illusions. They create a tolerable reality out of what is really a long, undifferentiated test of will. Swimming classes are not for the drowning child. They are for the drowning parent.

We dressed him in a wet suit, not wanting him to catch a chill, and because the suit had flotation pads around the chest, his proportions were those of a real swimmer: spindly legs and outsize torso and shoulders. His head, like the heads of all children, was too big, so that when I page through pictures of him at that age, I find myself staring at a caricature of the boy I had created: half swimmer, half reader. I am also staring at the father he created. My son, the only power under heaven that could drag his father back into the pool.

By now, we had arrived at a crisis in our reading. There is only so far down the canon one can go before even an atheist becomes self-conscious about overlooking the Bible. I thought back sometimes to Matthew’s story, found in no other gospel, of the wise men who bring gifts to the newborn Jesus. This captured something essential about my experience of parenthood. The impulse to give, and then give more. The compulsion to leave behind the place I had called home before, just to be at his side. This was a gloss I would have been ashamed to offer in college, a simple, subjective, dead-end one. I had been trained to read as a surgeon operates — dissect, find weakness, diagnose — and my atheism went hand-in-hand with this approach. It was the height of laziness to see nothing more in a text than a reflection of myself. Fatherhood, it seemed, had made me soft.

And so, at Christmas, I reopened the Bible. There are only two gospels, Matthew and Luke, that tell a birth story about Jesus. Since their accounts are almost irreconcilable, and since both of them depend on historical events that almost certainly never happened, reading them side by side was a reflex test, a stab at self-diagnosis, to see whether I had surrendered to contradiction and illogic. Whether my atheism was beginning to slip.

I read the first two chapters of Matthew, then the first two of Luke. If I had noticed the difference before, it had never made an impression until now. All the Gospels except Luke’s begin in the same voice: the omniscient third person, the sound of God talking. But Luke opens with a prologue in the first person. He acknowledges that he has written this gospel himself, that he isn’t the first to have done so, and that he wasn’t an eyewitness to the events of Jesus’s life. But he promises that he has taken pains to “investigat[e] everything accurately” so that he can “write it down in an orderly sequence.” It is hard not to be charmed by this scrupulous, almost self-effacing beginning. It piqued my interest. I read the gospel to its end.

Matthew and Luke are believed to have been written around the same time, and both by the same process: weaving together the earlier Gospel of Mark with a second document that recorded Jesus’s teachings. Considering this, the differences between them seemed stark. Matthew had placed so much stress on comparing Jesus to Moses; Luke placed very little. Luke’s audience must have been Gentile, since, in addition to this lack of emphasis on Moses, Luke simplifies or has to explain his “Jewish” material, as if his readers are not familiar with it. Perhaps for this same reason, Matthew’s bitterness and frustration — the gall of abandonment felt by a Jewish Christian toward fellow Jews who refused Jesus — is much harder to find in Luke.

Instead, Luke radiates love. His theme, more than that of any other gospel, is the innate goodness of people, a subject he is able to find everywhere. Eleven of Jesus’s parables exist in no other gospel but Luke, including two of the most famous: the Good Samaritan, about the unexpected mercy of our presumed enemies; and the Prodigal Son, about a wayward young man who returns home in shame, having wasted his inheritance, only to find that his father’s love and forgiveness are bottomless. This optimism and generosity are pervasive in Luke. It is hard not to feel that, in this author, Jesus has found the ideal messenger, a man able to see past misfortunes in order to keep heartfelt faith in a radical, transformative love.

The contrast between Matthew and Luke hits hardest at the end, where Matthew’s love of Jesus, and anger at Jesus’s death, leads him to those words seemingly bereft of redemption or forgiveness: “His blood be upon us and upon our children.” Matthew does not even change the devastating final words of Jesus on the cross, as reported by the Gospel of Mark: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Rather, it is Luke who changes them. And it is in Luke’s improbable version of the crucifixion that I see Jesus most vividly: as the hero of mercy and embodiment of love; as the man intent on seeing the goodness in us even when we give him no reason.

I see, also, Luke himself: his own mercy and love, his capacity to overlook the horror Matthew could not. As Jesus dies on the cross, crucified with two thieves, Luke adds a final story found in no other gospel:

“Now one of the criminals hanging there reviled Jesus, saying, ‘Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us.’ The other, however, rebuking him, said in reply, ‘Have you no fear of God, for you are subject to the same condemnation? And indeed, we have been condemned justly, for the sentence we received corresponds to our crimes, but this man has done nothing criminal.’ Then he said, ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.’ Jesus replied to him, ‘Amen, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.'”

Today I have three sons. The oldest are nine and seven. They are competitive swimmers.

At one of their practices, I recently discovered a group of adults training in the adjacent lane. So I bought a new suit and joined them. For the first time in two decades, I have a practice group.

These days I swim side by side with my boys, separated only by a lane rope. When the old feeling returns, that the pool is infinite and the lap endless, I peer through the murk of the next lane and I wait for a glimpse of them.

How hard they work for every yard. How desperately they want air but force themselves not to breathe. Every once in a while, they catch me watching. And when they do, they try to keep up. Their arms spin faster, their kicks start to beat the water white. Unconsciously, as if they have inherited this instinct, they veer over toward the lane rope between us. They draft off me.

The final words of Jesus on the cross, according to the Gospel of Luke, are: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” I push forward. Stroke on stroke, I try to part the water.

This essay originally appeared in The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, now available in paperback, and is reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster and the author.