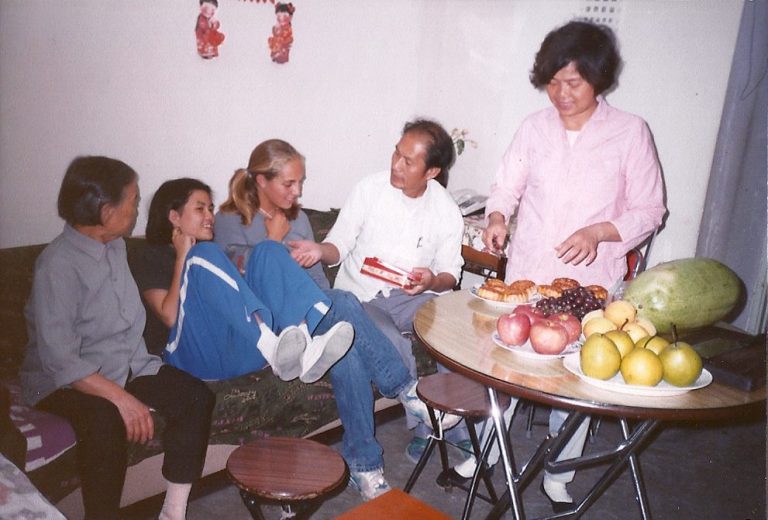

The author at her family's Beijing home (from L-R, host grandmother, sister, Solimine, father, and mother) during Mid-Autumn Festival, 1996. Image by Kaitlin Solimine, © All Rights Reserved.

Becoming Li-Ming’s Daughter

My Chinese mother, Li-Ming — who wasn’t my birth mother but insisted I call her “Mama” — cinched my raincoat’s hood around my face so my eyes were invisible. We stood together, mother and daughter, at the entrance to Fragrant Hills Park on a foggy autumn day, the hills swathed in red and gold.

“You’re going to be Chinese today,” she said, even though I was a 16-year-old white, blonde American living for a semester with her family in Beijing. It was 1996 and foreigners were uncommon in China; when I bicycled the city’s wide, empty avenues or walked the labyrinth of hutong alleyways still in existence, I stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. But, today, “Mama” didn’t want to pay the exorbitant foreigner entrance fee — instead, I’d pass as Chinese and buy the reduced Chinese ticket.

Minutes later, we successfully bought two “Chinese-only” tickets and triumphantly breezed through the gate. She wrapped her arm around my shoulders — despite only knowing me a few months, her love encompassed me with a physical closeness often unseen in Chinese families.

“Now you’re my Chinese daughter!” she exclaimed.

I didn’t want her to let me go. I didn’t know in a year she’d die of breast cancer.

After our hike in the Fragrant Hills, she insisted on the evening pre-sleep ritual she enacted every night for my Chinese sister, Xi-Xi, and me: “Wash your feet, you two!” For me, she dragged out the green plastic tub with dancing children etched on the inside; for my sister, a blue bucket edged with colorful flowers.

My Chinese father, Baba, heated a kettle on the stove. Steam rose as he poured the water, still smelling of rusted pipes, into our tubs. Impatient, I dipped my toes in the bucket, eager for warmth to envelope my feet as Beijing’s nights cooled, the apartment’s concrete floors frigid in colder months.

“Did his letter arrive yet?” Li-Ming asked.

I shook my head knowing to whom she was referring — my high school boyfriend who just started college.

“It will, it will,” she said. Sensing my disappointment, she took one of my feet in her hands, rubbing the pressure points along my insole, rolling from heart to gut. I didn’t know why she was so invested in this immature relationship but she regularly asked me about the boyfriend, rooting, it seemed, for his continued affection despite the fact he would soon forget me.

I tilted back my head and relaxed, the intimacy of this nightly foot rubbing now one I anticipated each evening, sitting alongside my sister who waited her turn. I’d never met a woman like Li-Ming — she wasn’t my mother, of this we were both clear, but it was as if she was meant to be. We made up for lost time in these sessions, discovering what it would be like to choose another mother over one’s own, another daughter. Xi-Xi indulged her mother this deflected affection, only occasionally sullen or defiant. I’d sleep so well after the foot washings, the day washed away in that bucket, the pressure of teenage angst and heartache relieved by a mother’s touch.

My American teenagehood was so different from this — I couldn’t imagine opening to my own mother in this way, a woman with whom I had the usual complicated mother-daughter relationship that boiled to an ugly head that year, my pushing toward independence only sending her clinging to control me, which only pushed me further away.

After Li-Ming’s death — of which I learned via a tear-dappled letter Xi-Xi sent — I returned to China deeply yearning to “pass” as Chinese. (I recognize how fraught it is to be a white American assuming this term). At 18, I traveled alone to China’s Northeastern rust belt, a polluted, desolate region, writing for a travel guide, and befriending new locals in bars each night. At 20, I studied at Peking University alongside Chinese students, discussing, in Mandarin, events like the U.S. “accidental” bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. I sang in a Chinese rock band, got romantically involved with the drummer, a bisexual man from Fujian. I wrote a novel situated in China. I was desperate to prove my Mandarin fluency, pursuing a graduate degree in Chinese studies and a Fulbright grant, eschewing the expat crowd but seeking a small, intimate circle of Chinese girlfriends.

I thought if I dug deep enough, even as a child I shoveled a hole to China, unsuccessfully, I’d find some kernel of what it meant to be Chinese and then I could be Chinese too. What I didn’t realize was becoming Chinese wouldn’t bring Li-Ming back, couldn’t backfill a familial history I wished existed, or overcome centuries of American colonialism abroad, an uneasy inheritance for any American.

Now, a new mother repatriated in the U.S., I speak solely Mandarin to my toddler; my daughter has inherited the aftermath of my obsession. Throughout this project, I never questioned why I was so eager to know China intimately nor did I recognize the privilege of my desired cultural assimilation. It wasn’t forced on me as it is often for immigrants. I didn’t lose or need to give up my white, American identity in the process.

But I was desperate to belong to Li-Ming’s China. And what was that, exactly? For Li-Ming, as she regularly said at the start of a meal:

“If I have a roof over my head, shoes on my feet, food on my table, and my family eating beside me, what else do I need?”

She was her generation’s Chinese daughter — well-schooled in the true heart of communism, the ways in which generosity could create an empathetic, egalitarian society, but that, in practice, humanity would cruelly vivisect. She had very little to give but gave selflessly. She never complained about her lack of material goods, while affluent friends and family in the U.S. regularly compared their financial lot with that of their neighbors’. Years later, Baba told me Li-Ming spent her entire savings to buy me the new Phoenix bicycle I carelessly bicycled around Beijing that autumn while she, Baba, and Xi-Xi muscled decades-old rusted wheels into motion. I never thanked Li-Ming for this gift, never recognized the lengths to which mothers — inherited and adopted — go to provide for their children.

As if to further my cultural dissolution, I disavowed everything American while in China: After the Belgrade bombing, I stitched a Canadian flag patch on my backpack lest I be mistaken for American while traveling alone. When in Beijing, I lived with my Chinese family in their worn-down, Soviet-era housing compound. I was embarrassed to enter a Starbucks or KFC.

While I remained tied to the version of China I fell in love with when I met Li-Ming, the country changed swiftly, and with the newest expressway paved over hutong neighborhoods, the latest shopping mall filled with Chanel and Louis Vuitton, Mama’s grounded, whole-hearted presence became more and more distant, her ghost barely visible behind the weighty urban outline of construction cranes, skyscrapers, and smog. I reached further: Where was she? Where was Li-Ming’s China?

In 2005, in Beijing for a summer of graduate study, I awoke to Baba poking me in the arm.

“Breakfast is ready,” he said. The typical table: a bowl of steamed soy milk, a fried dough stick from the corner shop, a boiled egg. Baba cracked the egg against the glass table top, handed it to me. When I think of Baba now, it’s the egg cracking I remember — the tenderest act of destruction and love. “We’re going to see Li-Ming today,” he said.

Two bus rides, a 20-minute walk, and a hailed taxi later, we were in the suburbs, smog clinging to tightly lined graves. Baba stood at my side, head genuflected before the smiling black-and-white portrait of Li-Ming on her grave. It was the first time I’d visited the cemetery since her death.

“Our American daughter’s here now. She keeps returning, don’t worry,” he said, wiping a tear off his cheek. His voice quivered: “She’ll take care of Xi-Xi when I’m gone.” A janitor swept nearby gravel. A bus horn shrieked. I leaned over, placed a bouquet on Mama’s grave, the yellows and oranges brash against the stone. The gravity of this promise was a new weight: To be Li-Ming’s daughter also meant inheriting a sister, and, with that, standing beside Xi-Xi at her wedding in a few years, agreeing to give a toast despite knowing she was marrying the wrong man.

Baba, not a man of emotional gestures, placed his hand on my shoulder, crying softly. Tears meandered down my cheeks too, but looking at Li-Ming’s bright-faced smile, a portrait taken a decade before I knew her, was like staring at a woman I’d barely known — or rather, a woman I thought I knew. In the years that passed since her death, in the shifting landscape of urban development around her old home, alleyways paved over by highways, corner vendors replaced by McDonald’s, bicycles rusting in heaps, cars clogging the ring roads pressing toward an uncertain future, I couldn’t remember the sound of her voice, couldn’t capture what I’d craved so deeply the decade before.

Living with her family as a teenager meant my relationship with them was also trapped within the bounds of a teenager’s world — like the love I thought I felt for my high school boyfriend, I romanticized Li-Ming, the mother I wished were mine, so generous, so sisterly, so warm of touch, but, in reality, who was she? China: It seemed ridiculous that one word, one border, defined what was extensively diverse, complicated, multi-faceted. The idea I could “study China,” or “be Chinese,” was a deeply disturbing ruse, as much as it was I could really be Li-Ming’s daughter. And if I could, would I want to?

Someone else’s culture seems much less complicated than our own; someone else’s mother more maternal than ours could ever be. Baba stood beside me, a “Chinese man” by passport and birth. Despite how differently we knew her, in this moment we were just two people who mourned the same woman — and, as if finally fulfilling Li-Ming’s deepest wish, her death made us family.

Twenty years after I first “passed” for Chinese in the Fragrant Hills, I put my daughter to sleep in San Francisco, checking my emails one last time, brushing my teeth. I’m still exhausted by early motherhood, by the demands of caring for someone I love so deeply, so unexpectedly, that I’ve lost a part of myself in the process. Suddenly, I’m overtaken by an urgent need to wash my feet, something I haven’t done in years.

After Li-Ming’s death, the foot washing happened occasionally at the old Beijing apartment, only ever at Baba’s insistence. The bedroom door would squeak open, Baba’s slippered feet shuffling past boxes of old clothes and books, everything my Chinese father, a hoarder of material goods, couldn’t let go of after his wife’s death. He never rubbed my feet (this would be too intimate a task). He’d simply hand me the canteen of hot water, a clean washcloth, and expect me to perform the rest.

I never asked if this foot-washing ritual was something Li-Ming brought into their relationship — it seemed more important to her — or if every Chinese person washed their feet each night (some cultural relic of folk medicine?). For all the studying, the desperate search to belong, I didn’t question the simplest act: Was Li-Ming’s insistence pragmatic or maternal? Whatever the reason, as I fill the tub with water and submerge my feet, I yearn for a life filled with foot-washing nights, mother-daughter gossip, the sloshing of washcloth, that familial vulnerability of two fingers pinching a foot. The simplicity of a relationship that isn’t inherited, but crafted with intention. The raw openness of teenagehood, of a full life not yet lived. Was this Li-Ming’s gift? Was it possible, in pulling off my socks and exposing my naked, blistered feet, in opening up my teenaged heart, I’d given her something too?

At home in San Francisco, I towel dry my feet and crawl into bed alongside my sleeping daughter, likely enacting a bedtime routine Li-Ming practiced for years in her crowded family bed, curling back the comforter, and nestling into my daughter’s small, needy body. I touch her feet, reminding myself that when she’s older, I’ll perform the same gesture, not because it’s something Chinese but because it’s something Li-Ming gave me. If I learned anything in the short months living with her, it’s that what Li-Ming gives must not be possessed, should be passed on.

Kaitlin Solimine is the author of the newly released novel, Empire of Glass, now available in paperback.