Mothering Ghost Babies

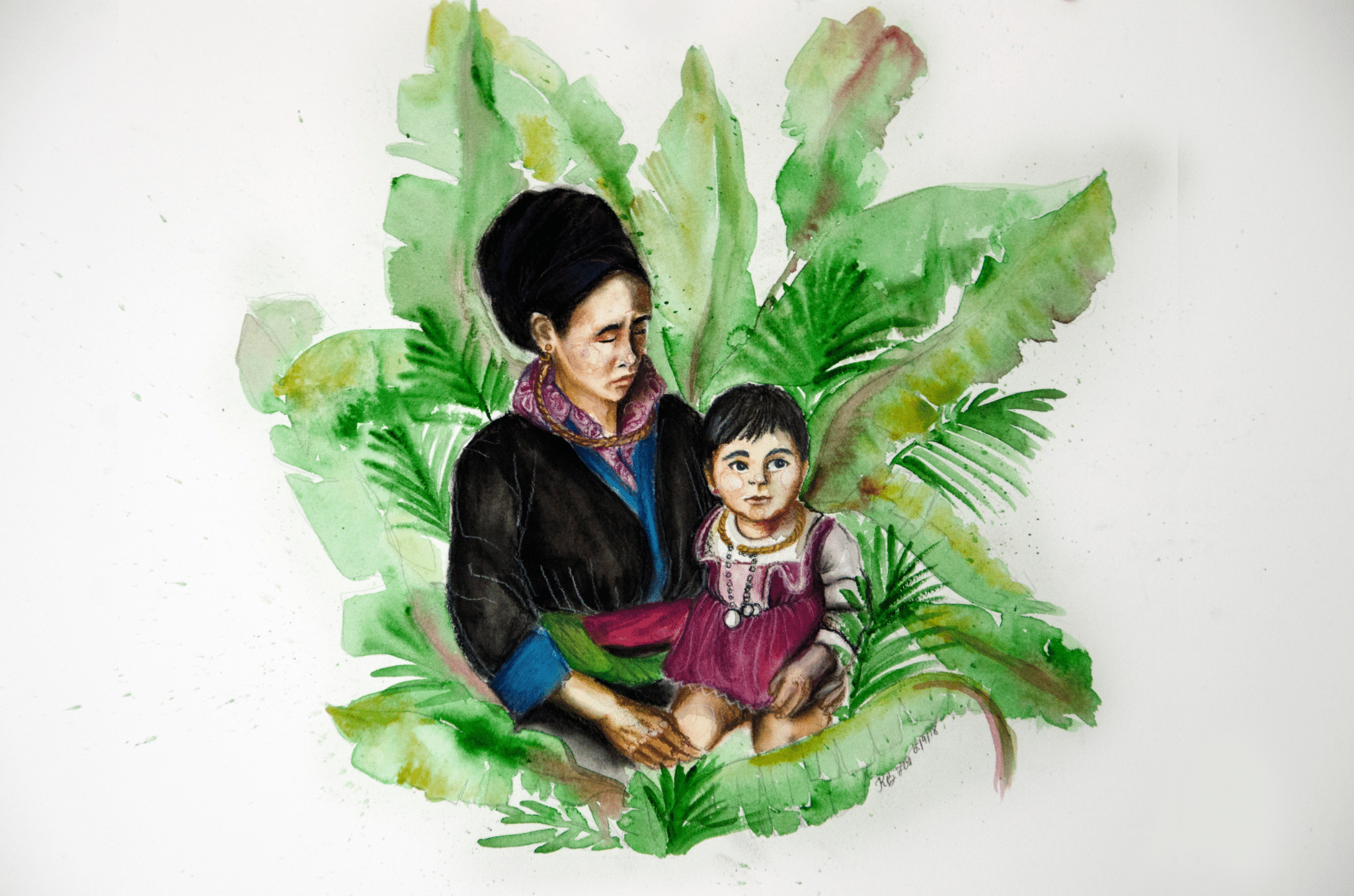

Image by KB Lor, © All Rights Reserved.

The first woman whom I knew loved ghost babies was my grandma. She had a daughter she talked of as beautiful, a little baby who died one sunny day beneath the shade of a tall tree, on the edge of a high mountain, in the lay of a steep field.

My grandma had loved her as a living baby for seven months. Her hair, dark and thick, bloomed about her round face. Her lashes were stout and fat like the trunks of the flowering trees that lined their small village. Her mouth was a red slip of a chili pepper against the soft paleness of her skin.

On the day she died, my grandpa had not been feeling well, so he had stayed home to nurse himself to health on the guest bed in the family’s thatched roof house. My grandma had gone to the gardens to tend to the weeding with her three older boys and precious little girl. She’d told the boys to look after the sleeping baby. They were playing a game of hide-go-seek among the young rice shoots, the growing corn.

Grandma was far south of the field when she heard an urgent call, “Mother, the baby is blue!”

It was the voice of her oldest son, an eight-year-old at the time.

My grandma had never been a fast woman. Her wide feet fell heavily on the earth as she trudged her way up the field. She dropped her gardening hoe, and in her haste Grandpa’s big Hmong knife slipped from the strap on her waist.

When at last she made it to the group of boys, to the figure of the baby beneath the shade of the tree, sweat dribbled from her heated face onto the blue thing that had been her baby, neck twisted, eyes rolled back. Her baby who had stopped breathing. Her baby whose death struggles must have been intense.

The boys hovered around them, each saying something their mother could not hear, as she lifted the soft weight of her baby into her arms, felt the dangling of arms and legs.

My grandma said it was clear to her that the thing she’d lifted was no longer a baby. It was a dead pig. Some forest spirit with a cruel and malicious nature had played a horrendous trick. It had taken her baby while the boys were busy playing and had replaced her with the corpse of a dead pig. Still, the hands looked like that of her baby’s, pudgy fingers and fleshy palm, so my grandma held tight to those hands as she ran with the weight of the thing in her arms and cried for her boys to run and lead the way home toward my grandpa.

By the time my grandma made it home, the little body in her hand was stiff and cold. It was clear to all the villagers, who’d heard her cry and ran out of their homes, that my grandmother’s beloved daughter was no more.

The funeral was brief, for the life that had been taken had been short. The guides who led the little spirit to the ancestors had only a small stretch of road to walk in the afterlife. The rituals took no more than a day, the burial no more than an hour, but the grief would last a lifetime.

Grandma loved the baby in the days after death just as she had loved the baby in the days after her birth. Her breasts ached with milk. Her womb hungered for the warmth of a beating heart. Her heart could no longer find its home in her chest without the beat of her baby’s close by. Grandma cried for her first daughter on the path to the garden every day.

In the mornings, she yelled in a voice full of hope,

“Little One, your mother is calling for you and crying for you. The sun has just begun its course across the high heavens. Heed your mother’s calls, heed her cries, and find your way back to me.”

In the evenings, she whispered in a voice full of sorrow,

“Little One, your mother is calling for you and crying for you. The moon will soon start its course across the high heavens. Heed your mother’s calls, heed her cries, and find your way back to me.”

My grandmother cried for a long time, she cried across the birth of her six younger children, two of whom were daughters. She cried through all of the births her grandchildren. She cried until the very end when there were no more tears to cry. She cried right up until it was time for her to meet the only child she’d ever buried.

I grew up with my grandmother’s cries. They were part of her, a part I loved. When her tears fell for that ghost aunt I’d never met, the one who never grew up, who never screwed up, who lived in memory just as she had in life: as a precious little baby, her dark hair shining like sun rays away from the brightness of her face. It was always obvious to me that my grandma’s cries were cries of love, love not for me or others, but for that one person who’d taught her about the fragility of motherhood and its tremendous strength, how it lives beyond life and death.

Because I grew up with my grandmother’s cries, I was not surprised by my mother’s silence in the wake of all the ghost babies she delivered into the world, whose life and whose love have now transferred to me and my living siblings. After me, my mother had six miscarriages, all little boys, all formed enough so the adults could see that they were baby boys, but born far too small, and sometimes too blue, and other times too wet with blood to survive. Gaze trained far from me, eyes dried, my mother used to tell me about how much she loves me, how much that love belongs to me, but how much it was rooted in the other babies who came after me. She said that the death of each baby taught her how hard life was and reminded her of how strong I’d been. It always felt like I was getting love I had not fully worked for, credit where it wasn’t due, but the light of my mother’s love, the softness of its touch, the gentleness of its hold was such that instead of staring into the far distance of possibilities denied I saw only what was possible.

When I grew up and I fell in love and I got married and I started thinking about my own probable babies, I did not think of the ghost babies in my life; I thought only of the live ones I saw in the arms of the world. When I was pregnant, I was filled with thoughts of the future, not at all caught up with how the past is what anchors us in the present.

It was not until the baby died inside of me at nineteen weeks, and I had to deliver a dead baby into the world, that I thought back to my grandmother’s story, that I rested on the strength of my mother and the babies whose share of love I had taken fully and gratefully.

My baby was more light than substance.

He was silent, but he sang a song full of sorrow.

The grief counselor suggested we name him.

Jules. An English name I had heard only on television. A place I had never been. A possibility I would never know.

In the Hmong culture, we bury our dead babies. We don’t have funerals for them unless they have known life. We send them back to the land of the ancestors, to the table in the sky, where their paperwork awaits, incomplete. In the Hmong culture, they had not signed onto life with us. The deal was not yet done. Thus, their return to correct documents, to await new approvals, to learn how to sign their names.

And yet, here I was, Hmong in America, a world and oceans away from the land of my ancestors, from the place that had called me from the clouds.

I buried a memory box in the wake of a baby’s body. In it, there was a doll’s blanket, a bit of blood on the corner, the red blood of my child, now the color of rust. Inside it, there was a paper with his small foot print on it. A birth certificate that is not official but real. Inside that memory box, I buried the hopes and the dreams I had for a baby boy I had started to love believing there was nothing to lose.

I buried my son beneath a tall tree on a small island in a place full of people. I buried my son in the dead of winter, the earth frozen and hard. I imagined the tree in spring, full of buds that would unfurl into leaves, the tree in summer, heavy with green, blossoming beneath the bright sun, shade and shelter from the harsh rays, the tree in autumn, raining golden leaves upon the ground, a cover of colors bold and unafraid, and then the tree in winter, waiting to welcome the little feet in their soft sole shoes walking and running, jumping and falling, sitting and sleeping on the base of that tall tree where so many people go.

Like my grandmother and my mother, I mother a ghost baby. He is with me on a gray winter’s day in a coffee shop with red awnings, listening to the talk of men and women nearby, talking about cousins and faraway coasts, crabbing and coasting among the waves. He is with me in the car when I drive to pick up my daughter. He is there in my arms when I crouch down to hold my little boys close. He is with me late at night when the world is quiet except for the far sounds of sirens. He is with me early in the morning when I look out my bedroom window and I see the birds perched side-by-side, fluffy balls of feathers, sitting stiff on the telephone lines. Like my grandmother and my mother, I cry for him, and I look for him with dry eyes toward the other side of life.