Image by kychan/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

‘Boyhood’ and the Grief of Lost Time

There’s a particular sadness about the first moment you realize you’ve spent away a period of your life that you will never get back. As I’ve begun to pass certain milestones in my life, I’ve started to experience the great wistfulness of hindsight more frequently — how it allows you to articulate something important about living, but only after it’s too late to change anything. I wish there were a more succinct word for the feeling, that perspective. It’s more lucid than nostalgia, weightier than sentimentality. It’s what I felt when I hugged my parents goodnight the night before I left home for college; when the winds of Lake Michigan punctuated the laughter of my college friends the night before we all said goodbye to each other; when I drove across the Golden Gate Bridge, alone, away from some scrappy form of a family and toward a new life.

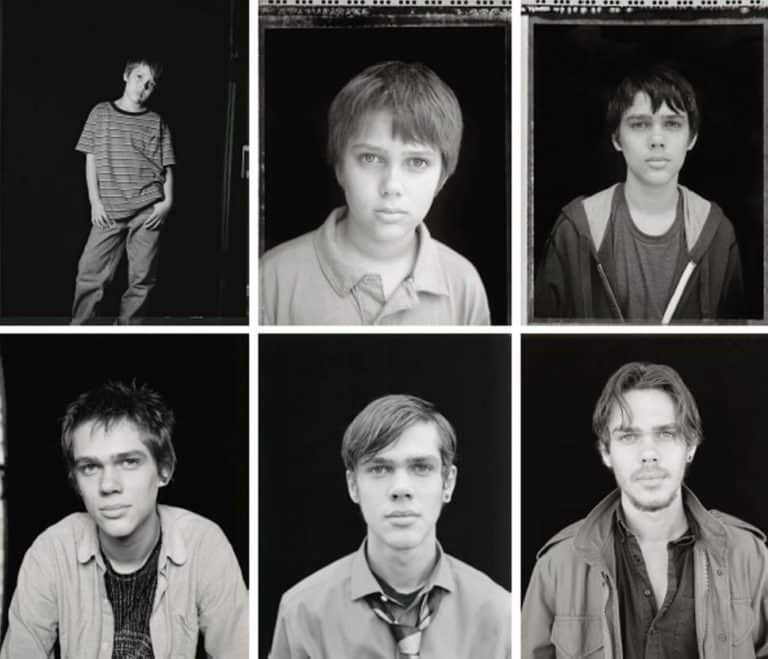

I’m not sure what events of the world conspired so that Boyhood would be released the summer of 2014, the same summer I turned 20, deeply lost and lonely. At the time, the movie did not so much change my life as it reflected it back at me: Boyhood follows the childhood of Mason, a boy living in Texas with his sister and divorced parents. Though the premise itself may feel somewhat generic, the movie’s structure was unprecedented. The director, Richard Linklater, chose to film the movie over the course of 12 years with the same cast.

Above all, time is the protagonist, as we witness the actors aging — growing taller, gaining and losing weight, trying different hairstyles — in real time, along with us. Mason begins the movie as a young boy gazing up at the sky in daydream, and ends as a pensive high school senior leaving home for college. In between, we see him in the context of the many worlds he inhabits, as he moves from town to town with his sister and mother; as his mother attends college and struggles to make ends meet; as his father goes from being a musician to remarrying and starting another family. Watching the characters grow and change, there’s a sense that time forgives — if you grant it the patience to pass over you.

The movie may have been a gift in the amount of time and patience it took to produce, but it felt like even more of a gift for those of us who turned 20 that year. Linklater cast Ellar Coltrane — who was born the same year we were, and whose coming of age essentially paralleled our own — to star as Mason. As someone who grew up in Texas, watching the movie has always elicited a strange form of déjà vu, the amusing thought that we could have been in the same homeroom in elementary school; stood in the same line for the midnight release of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire; or visited the University of Texas on the same weekend (all vignettes woven throughout the movie). It was as if Linklater was saying to us: Your childhood happened — and it is also fleeting. But here are the moments you might have shared.

Though we are following Mason through his formative years, we are never sure of how these moments might be shaping him as a person. Scenes unfold and then cut away, with very little time for reflection. Even in the tensest scenes — when Mason’s alcoholic stepfather throws his mother to the ground, and they flee the comforts of a large suburban home to live in a friend’s home; when a teenage Mason is scolded by another drunk “father figure” — the camera barely blinks before moving the story along.

Linklater seems to want it no other way; we are charged only with living the moments of Mason’s journey for what they are. Though this was not exactly what my 20-year-old self wanted. Yearning for conclusion, I tried searching for meaning in all the conventional questions. What was the moral of Mason’s story? What wisdom was Linklater trying to impart on us? And how did it apply to my own life, so parallel to Mason’s?

But it is in this way that Boyhood articulates what is inarticulable about being young and stumbling toward adulthood — that maybe, in the graceless process of maturing, there’s no better resolve than to simply bear witness to your growing pains, to live them through. In the four years since its release, I’ve come back to Boyhood again and again, at the junctures of my life when I’ve been desperate to make sense of how difficult this is. I return because, as a movie that evades any sort of resolution, it offers the greatest one of all: That there is no resolution, only the vast expanse of continuity, of one moment leading to the next and then the next. And that we have permission to take joy in that, to savor each moment not for what it means, but for its mere existence. Because whether we want it to or not, time finds its way to shepherd us from one experience to the next.

In the last moments of the movie, we see Mason driving along a seemingly boundless road, away from his home, and toward college, his new life. At this point in the movie, we’ve witnessed twelve years of happenings. And yet — the yellow line dividing the asphalt continues on and on, toward the horizon, the possibility of a different perspective.

Often, we’re only offered the opportunity for perspective when we’re looking back, and it’s too late. But what I love about Boyhood is its reminder that there’s another kind of perspective, one that opens us to the endless beauty in the moment right before us. It humbles. What a gift it is to recognize this, to be able to hold it in your hands or bear witness with your eyes: That this moment is it — this is all it is.