Love and Fire

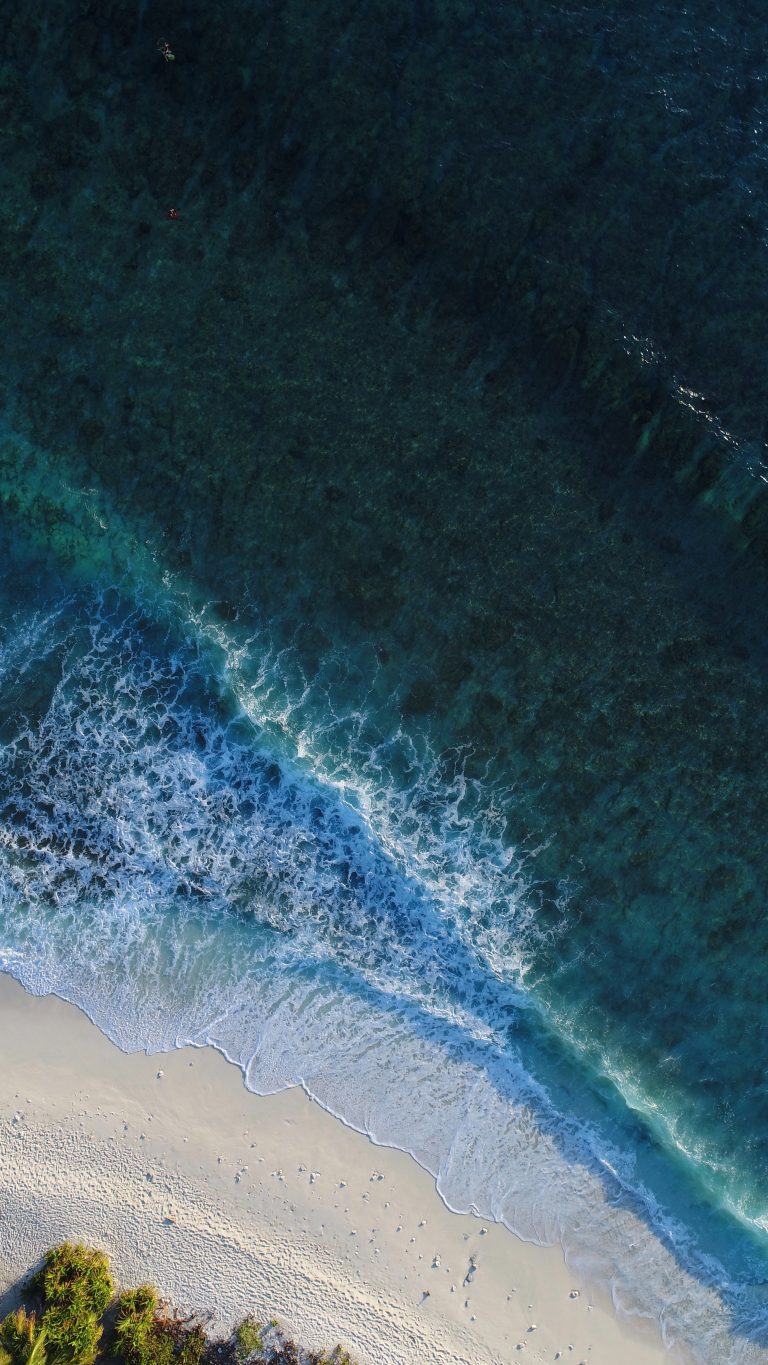

Image by Matt Howard/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

At 4 a.m. on Tuesday, Sept 5, 2017, I sent an email to my editor in New York: The Eagle Creek Fire had crested the mountains above our home in rural Oregon. The book manuscript that I was supposed to have turned in by the end of Labor Day weekend — The Gospel of Trees — had been loaded into the car along with fifteen years’ worth of source documents.

We were just outside of the mandatory evacuation zone, but winds had whipped the flames across thousands of acres overnight and neighbors at the end of our road had been forced to leave. So much forest had already been lost. The dog whined at the door and I turned on the porch light to see a herd of elk clustered in the open field, restless and wary. Charred leaves floated down from an orange sky.

We had shaken the boys awake just after midnight, but the nine-year-old had just rolled over in bed, convinced it was all a bad dream. Our eldest son had stumbled around and packed a few favorite books and Legos, then fallen asleep on the couch. My husband checked social media for updates from the sheriff’s office. I sat at our dining room table, bare feet on the floor, and found a blank piece of paper and a pen to gather my thoughts. I thought of refugee friends without the luxury of time to pack or vehicles to carry them to safety, much less time to sit and write, but the gesture felt somehow grounding. It was how I had always faced loss.

I had been fifteen the first time that I was evacuated, from a missionary hospital in Haiti, and my journals from those years are riddled with questions. The collapse of the Duvalier dictatorship had touched off a tumultuous decade in Haiti. My father was a forest ranger/farmer turned missionary agronomist and had spent his days hiking into the eroded hills to preach the gospel of trees, while I barricaded myself behind novels on the missionary compound. We had come, so we told ourselves, to help, but many of the people we lived among were tired of our pity, tired of being condescended to by outsiders who told only a certain kind of story about Haiti. Pity, I was slowly realizing, was corrosive. It was long past time for a new narrative. A rumor circulated that the missionary homes in Limbé would be burned to the ground by morning.

In writing The Gospel of Trees, I had pored over my parents’ journals so often that at times it felt as if I was inhabiting my mother’s body along with my own. The night before we were evacuated from Limbé, she had sat at our dining room table, bare feet on the concrete floor at midnight, and confessed to the page how frightened she was. Gunshots exploded across town while my sisters and I slept in the next room.

Memories of the past merged with the present. I was in my forties, the mother of two, with a forest on fire just over the ridge from our home in Oregon — and I was fifteen again. I realized that I had never once cried during that first, traumatic evacuation. I had turned the grief inward, carried it in my body as a tree hides a scar in its rings.

We can make prisoners of our own bodies. We can turn pain against ourselves. Or we can turn it against others. I want to believe that we can also be transformed by loss.

By dawn, the winds that had pushed the Eagle Creek Fire thirteen miles in sixteen hours had temporarily subsided, but the sky remained an ominous red. My husband and I decided not to risk it. Family members drove out to help us transport the family dog, a sick kitten, and our six baby chicks. We walked through the woods by our house one last time. I brushed my fingers against the oemleria and western red cedar that we’d planted, the alders and big leaf maples, the thimbleberry and sword ferns. I wanted to apologize: We did not love you as you deserved.

When we reached Portland, more than once a stranger asked me how I was doing and when I told the truth, they’d start crying and admit their own fears. The prospect of losing the Columbia River Gorge to fire felt like losing a family member to a sudden-onset terminal illness that none of us had seen coming. One woman’s 70-year-old parents were inching through traffic in Florida, trying to escape a hurricane. Mexico was being pummeled by earthquakes. Houston was still underwater. There was so much to mourn.

What does it take, after the catastrophes that make the news, to rise up, to keep going? After the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, a Kreyòl phrase was repeated and printed on T-shirts: Annou leve kampe. Let us rise up and take our stand.

A crisis measures how we respond to those around us, how connected we are, what we do when we’re afraid.

When I returned to Haiti in 2010, twenty years after my family had lived in Limbé, to report on post-earthquake recovery efforts for the radio program This American Life, I visited a Haitian-run medical clinic in the north that was treating all patients free of charge. Neighbors who owned only two pairs of shoes had donated their only extra pair to those who had lost everything in the earthquake. Nearly every home was crowded with refugees from Port-au-Prince. Carpenters and doctors were driving back down to the epicenter to improvise splints out of cardboard and rebuild homes.

It is easy to slip into sensationalized language when faced with immense loss, but it matters how we talk about places that have suffered from catastrophic events and what images we use to represent them.

During the Eagle Creek Fire, strangers slowed traffic and asked the locals — displaced business owners and families that were driving miles out of their way to prepare food for the firefighters — where the best place was to take photos of the flames, like paparazzi at a funeral. I can only guess at how many Haitian citizens have been photographed, without permission, as objects of pity.

Oversimplified narratives can yank open wallets but cause a far more lasting damage. As a missionary’s daughter, I remember only too well the fundraising newsletters we sent to our supporters, drawing attention — far too often — to Haiti’s poverty, while overlooking the strength and dignity of those around us. The so-called “poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” is so much more complicated than the dismissive tagline would suggest. As the first and only slave colony in the history of the world to win its freedom, sixty years before the United States of America declared slavery illegal, Haiti is a nation of strong, proud individuals with unique and complicated stories.

Those who have endured crises don’t need our pity; they need our respect.

When I took my sons to Haiti for the first time in 2016, we looked not for the ways that we could help, but for what we had to learn. We asked questions: What do you love about where you live? What are you proud of? What do you find beautiful? What do you want to protect?

At least one news outlet described the Eagle Creek Fire as “a community devastated, a forest destroyed,” yet when I interviewed neighbors along the Columbia River Gorge for Topic magazine, I heard far more nuanced stories.

A Forest Service ranger named Sharon Steriti had hiked miles into the night to help more than a hundred stranded hikers who were trapped on the wrong side of the fire. When she found them, in the dark, hiking by the light of their cell phone flashlights, they had already created an improvised system to make sure that no one got separated. “It’s okay to be afraid,” she said. “We’re in this together.” She propped her backpack against a tree and hung a light overhead as they sheltered in place along the trail, so that anyone who needed to talk could come and find her. The fire was a faint orange glow through the trees. They all made it out the next morning, hiking miles over the mountains to safety.

Catastrophic events reveal us to ourselves. They expose our fears; show us what we will risk everything to save.

In towns on both sides of the Columbia River, volunteer fire fighters drove into the blowing embers to evacuate their neighbors. Women backed horse trailers up strangers’ driveways to rescue agitated animals. Elderly volunteers with the sheriff’s office went door to door to make sure that everyone was safely out.

The best possible emergency preparedness, it turns out, is to get to know your neighbors.

As vulnerable as it feels to acknowledge it, increasingly unpredictable weather systems — hurricanes, floods, landslides, drought, fire, ice, megastorms — will impact all of us, no matter where we live. We are all in this together.

During the Eagle Creek Fire, entire trees ignited in the heat and the flaming crowns snapped loose, blowing as far as two miles downwind. As terrifying as that night was to live through, whole sections of the forest remain untouched because the leaping flames left behind a mosaic pattern of mature, resilient trees that are even now dropping seeds. The charcoal has enriched the soil, creating a more varied habitat for birds and deer mice, and for the elk to graze. The fragile, post-fire ecosystem is also more susceptible to invasive weeds, but if allowed time to recover, the earth will heal. It is still possible for a new story to unfold.

This, I believe, is what the trees have to teach us — that what looks like the end may just be the beginning.

Still, it is one thing to appreciate a metaphor, another to live with post-traumatic stress. Our home was not, in the end, destroyed by the Eagle Creek fire, though for weeks the smoke hovered over the local schools, the neighbors’ horse pastures, the trailer park. And although I know that the danger is past, I still wince when I see pillars of smoke rising from a burn pile, imagining in those raked piles of leaves and fallen branches another looming sorrow. I am not the only one. The local fire station fields far more worried calls from neighbors than it used to. We are still jittery. On edge.

It hurts to love a place that we are at risk of losing.

The boy who threw fireworks into the gorge, never anticipating what his reckless act would consume, received death threats on social media. He was fifteen years old. For his own protection, his name has not been released. I, too, was fifteen when I learned that life can take unexpected turns. Loss is the one human experience that we all share.

I used to believe, as a missionary’s daughter, that I was one of the good ones. I no longer believe this to be true. I’m no longer sure there are any good ones. There’s just us: flawed and fumbling, complicated and complicit. Capable of doing harm without ever intending to, but also capable of unexpected courage. Which is good, because we’re going to need courage to write, together, a different story about our collective future.

This past summer, in the month of August alone, more than 550 fires burned across Canada and the U.S. The sun, hidden behind a scrim of particulate-heavy air, appeared sunset-orange at mid-day. The philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined a new word, solastalgia, to evoke the feeling of distress when one’s home is under threat by a looming environmental disaster; our collective nostalgia for a lost sense of solace.

There are days when I feel that I cannot bear it, that it costs too much to love this imperiled earth. All of that old grief from childhood comes welling up in me: watching soil slip down eroded hillsides in Haiti, leaving the farmers hungrier and the coral reefs buried under displaced topsoil. It aches, watching communities and ecosystems upended, even as my privilege shields me in a thousand ways from the worst impacts of climate change.

I want to bury that loss deep, so that I can no longer feel anything. Retreat into cynicism and apathy. Break up with this earth before she breaks up with me. Numb myself with a host of distractions. But the alternatives to love are paltry. When I meet someone whose life appears free from the burden of love, I do not envy them.

The deepest truth about being human is that everything and everyone I love, I will lose. It may hurt to love this broken, beloved earth, but grief wakes us up, reminds us that we are connected. And the story isn’t over yet. I can still pull weeds and plant trees. Listen to farmers in Haiti and to my neighbors in rural Oregon. Stack stones and create land art. Collect mushrooms from the woods, throw handfuls of onions and cilantro into the pan. Teach my students how to listen to their own stories and to give voice to whatever strength is hidden in sorrow. Curl up with my sons at the end of the day and say thank you for everything in this day that was irreplaceable, that we loved as best we could.

Dear Earth, I find myself praying these days: Please teach us how to listen.

Love is all we have. There are no guarantees.

Share your reflection