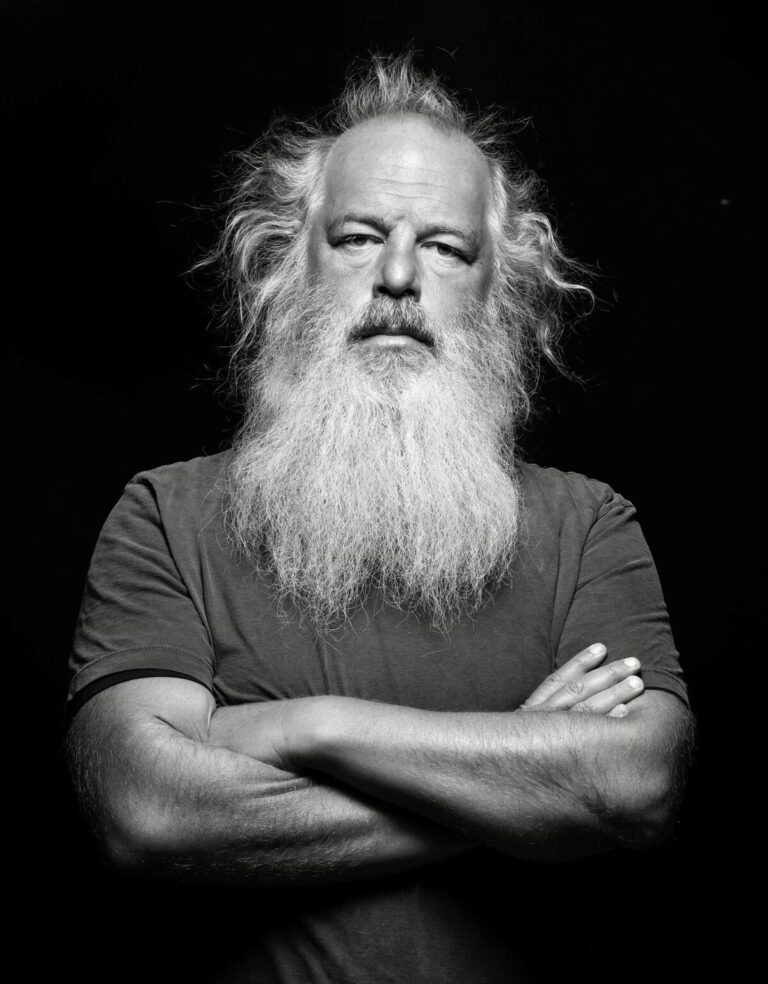

Image by Pietro Naj-Oleari.

Meditating While Drawing Blood: The Spiritual Gift of Donation

I am a student of Buddhism, but I am not a great meditator.

Although I know how beneficial sitting practice can be, I am lazy and easily distracted and I forget. After my last weekend-long meditation retreat at the New York Shambhala Center, I resolved to sit more often, for longer periods of time. As part of my spiritual path, I am also working on facing my fears and doing more good in the world. So when my appointment to donate platelets popped up on my calendar, I thought, here’s my chance for a nice, unbroken period of peaceful sitting combined with the chance to scare myself a little and help someone in need. What could go wrong?

As a member of the AB tribe — only about 5 percent of the population shares this rarest blood type — I had assumed, wrongly, that my “universal recipient” juice wasn’t desirable and that I should leave room for those with more accommodating blood types to donate instead. But last month, during a snowstorm here in New York City, I saw the blood emergency headlines in the papers, put my boots on, and headed to the donor center, figuring that my blood was better than no blood at all.

I sat back on a folding cot as a technician put a needle in my arm and filled a bag with rich-looking red blood. Simple enough, I thought, and looked over at a row of people resting on comfortable-looking lounge chairs — some with headphones, others watching television. All of them were there when I arrived and still there as I left. “I feel bad,” I told the tech. “I’m done and those people are still here.”

“They’re donating platelets, the clotting components of the blood,” she told me. “It takes a bit longer, and only certain people can do it. AB is the universal platelet donor.”

“AB! That’s me!” I thought. My envy for the comfy chair people turned into a sense of familial warmth. That’s where I belong, on the planet of the platelet donors. What’s inside me has more value than I realized.

The process can take about an hour and a half. As blood is removed, it’s spun in a centrifuge to separate the platelets and then returned to the body through the same needle, over and over until the process is complete. One platelet donation can serve multiple people, including cancer patients, accident victims, and people with blood disorders.

Perfect, I thought. I will sit in that nice chair and synchronize my breathing with the machine’s process, letting my heartbeat infuse my out-flowing life force with peace and warmth for people who are suffering. What better time and place for lovingkindness meditation and an opportunity to say, “May you be happy. May you be healthy. May you be safe. May you be free.” — to the technicians, to the other donors, to everyone in New York City and on the East Coast, the United States, and the world.

All week, I had an ache deep in the seams of my shoulders. Don’t take aspirin for 72 hours before you donate platelets, the email from the donor center reminded me. I tried to use the muscle pain as a mental gong, a reminder that I was purifying my blood, not for myself but for those who would receive it, all the while fantasizing about swallowing an Advil the size of my fist.

As I walked to the donor center on Friday night, these words came into my head, matching the rhythm of my feet on the pavement, “May the Lord accept the sacrifice at your hands for the praise and glory of His name, for our good and the good of all His Church.”

I am not a Catholic, but I went to Catholic school and I married into a Catholic family. I have been to enough Masses that those words, uttered by the congregation before the priest turns the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, come to my lips easily. It’s the mystery of transubstantiation, something I believed in once. As I prepared to make my tiny sacrifice, I said to myself, “May my platelets be accepted by those who receive them, for their good and their health.”

At the center, I filled out the form that every donor must complete every time they donate, a moment to take inventory of one’s life. As I checked the boxes, I was pleased to relate that I haven’t injected drugs or had sex for money, but I was surprised and disappointed to realize that I also haven’t traveled outside the United States and Canada in the last few years. I suppose I’m living on the Middle Path these days.

In the lounge chair, I receive instructions: once the needle is in my arm, I will begin to watch the monitor. I will squeeze a ball every three to five seconds during the donation cycle, and then relax my hand for a few seconds during the return cycle. The machine will donate and return, donate and return for about 80 minutes.

Okay. So it’s like a video game. I won’t have the chance to lose myself in meditation, but I can still keep my intention, to transmit lovingkindness while my blood is being drawn. Except I was never any good at video games: the monitor begins to beep. Low pressure, it warns. Though my blood pressure is fine, my squeezing isn’t working well enough to keep the flow going. There is a flurry of activity as the technicians try different techniques: blankets are piled on top of me, my squeezy ball is replaced with a hot compress, and an ice pack is placed behind my neck. I try to visualize my heart pumping like a steam engine, my veins flowing like a wild, rushing river. No dice.

The robust-looking dude in the chair next to me is donating double red cells. I watch his collection level go up, up, up as my monitor continues to stutter and beep, stutter and beep. Eventually the techs run out of tricks, and they take turns babysitting my noisy screen, silencing each alarm as it rings. They are calm, sweet, and funny. But I feel like a bad patient, a drain on their resources instead of a fountain of vitality.

The bouncy theme music of Seinfeld begins to play from the large TV in the corner — a welcome distraction. But, dammit, it is an episode that sets my teeth on edge: Kenny Bania and the Armani suit. As the debate over whether soup qualifies as a meal rages, I try to offer compassion to Jerry, to George, to Elaine, to Kramer. Beep. Beep. Beep. A tear of frustration comes to my eye, then another. Quit it, Gretchen. You can’t spare the fluids right now. Everything is workable, my meditation teacher says. My heart is open, even though my veins are not. My platelet bag fills gradually, drop by drop.

At last I get my cranberry juice, my pretzels, and my thank you. It’s probably not a big deal, the tech tells me. It might be dehydration or maybe the needle went in wrong. You can try again in a couple of weeks.

Try again. The most important lesson I have learned in my years of meditation practice: it’s not about how long you’re able to sustain your focus. What matters is how often you notice that you’ve wandered off, and you come back. Every journey back to your intention renews your mind and your heart.

Platelets need to be transfused within five days. There’s a good chance that my blood is flowing in someone else’s body right now, giving them strength. Meditation is not the only path. I know that next time I sit down to practice, I’ll be in that comfy chair, heart open, squeezy ball in hand.