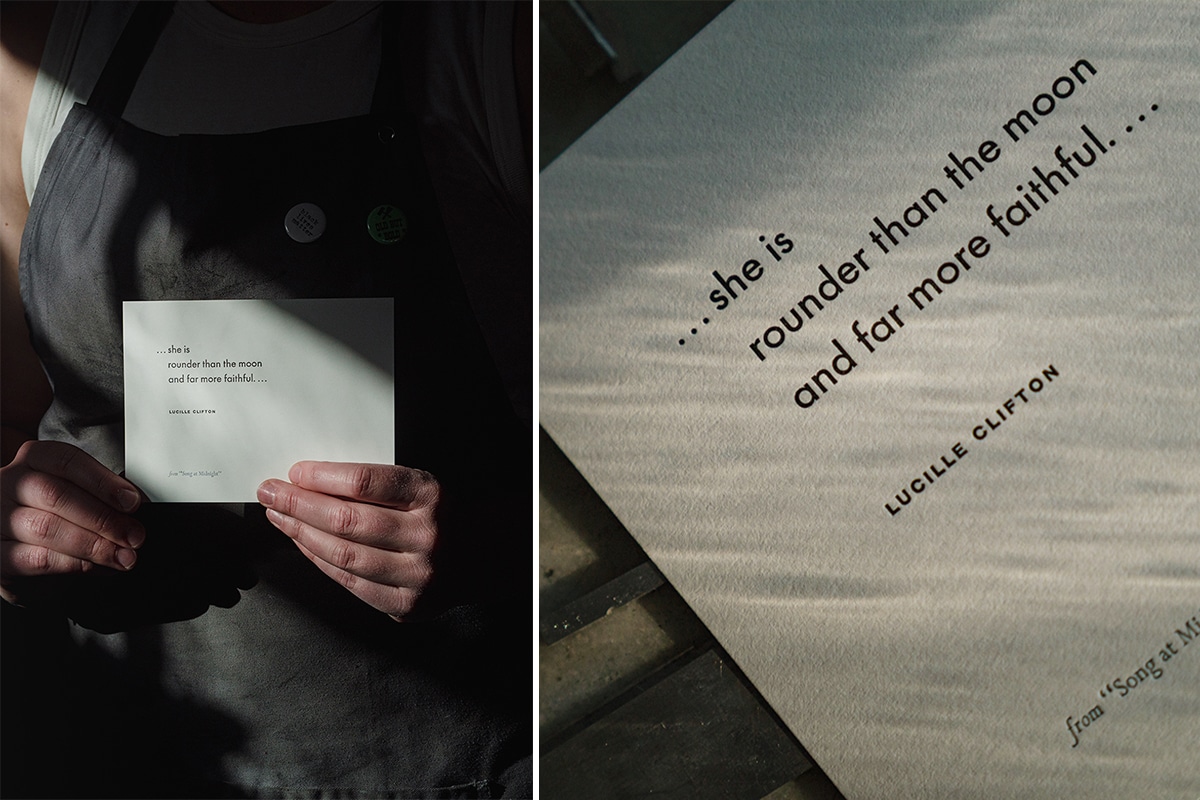

Myrna Keliher, photographed at her letterpress print shop, Expedition Press, on Thursday, Oct. 29, 2020, in Kingston, Washington. Image by Jovelle Tamayo, © All Rights Reserved.

Meet Myrna Keliher

If you have been following this season of Poetry Unbound, you may have noticed the individual prints that accompany each poem. Each one is designed from handset metal type and printed by artist Myrna Keliher. In 2012, she founded Expedition Press, a letterpress print shop based in Kingston, Washington that focuses on poetry and type. Their mission is to deepen regard for language and increase access to poetry.

How did you come to work with The On Being Project?

One night I was working late, setting type for a big project. My friend Carolina sent a link to an On Being episode that featured the poet whose poem I was setting (“Sweet Darkness” by David Whyte) and I listened to Krista and David’s conversation while I pieced the poem together letter by letter. That was four years ago. I sent a copy of that broadside off to Minneapolis in thanks, and began paying attention to The On Being Project. Small serendipities kept occurring between things I was thinking about, working on, and the content On Being was putting out.

Two years later, I was scrolling Instagram and saw a question in the caption of an On Being post: “What does it mean to embrace grief when it feels boundless?” I didn’t (and don’t) know the answer but the question rang deep and useful. I asked permission and built a print around that question, and sent copies in thanks. (I wrote a blog post about that project here.)

Then, in January 2020, I opened an email announcing Poetry Unbound. I read the podcast description and it felt like it was giving a gift of new language in describing my own work. So I wrote to Erin at On Being and asked to collaborate! We kept in touch and the opportunity came to make artwork for Season 2.

What themes or guiding ideas helped shape the work as a whole? What did you keep in the back of your mind as you were working?

Well, the ellipses (laughing). But really, in a concrete sense, finding a solution for them held together the series. Of course, the primary shape of the work comes from the language itself; but also, the fact that we needed to set tight constraints from the outset with such varied text. Committing to a format without all the excerpts invited a lot of deep breaths and welcoming of the unknown. And then, my ankle injury — that was such a huge slowdown as I was about to ramp up for production, and it changed the process a lot. Suddenly, I was only able to design a few pieces at a time. It made me rely more heavily on the initial constraints, and also let me sink deeper into each piece. It was a beautiful thing to hang out with each poem, poet, line for longer than I thought I could or should. And that’s saying something given that I set type one letter at a time.

In the back of my mind while I was working, I always thought of the poems, always the poets. Thinking about how to honor the excerpt on its own, and the poem as a whole, and the poet who wrote it. Also, there was tension between a call for bold, contemporary typography and a love of traditional styles, plus the fact that it had to be legible at a glance on little screens in people’s hands. And the limitations of my type collection. So it was a balancing act all the way through.

What does your art say about you?

My art says that I am methodical. Attentive to detail. Sparing. That I love language and making space around it. That I care for words and for people who work with words. My art says that I am staunchly impractical while simultaneously wedded to what’s useful. That I depend on poetry. That printing poetry remains the most useful thing I can think to do each day.

What draws you to letterpress printing?

I love the physicality of it. How you can hold words in your hands. Build sentences out of metal. Press them into paper. I love the smell of ink, the sound of the old presses, the feel of the paper in my hands. The timing. The slowness and the quickness. The deep hours of pondering and the clear moments of decision making. I love printing. I really love printing. I also love the immediacy of a print in someone’s hands, especially when it’s their own words.

Walk us through your creative process. Where do you begin? How do you know when you’re done?

I begin with reading. I spend months, sometimes years with a text before I approach an author or pull type. Language has to stick in my head — when I find myself reciting it to other people, then I know I want to work with it. Every day, first thing when I wake up (well, technically second thing. I make coffee first) I write three pages, long hand, stream-of-conscious, that I never read. Morning pages. I discover a lot of things about myself in those pages. I’ve been writing them for nine years now and I think it’s the single most important part of my creative process. That, and making time to be outside.

Sometimes the conversation with a poet or client or neighbor comes first, but always there is a quiet period of deep alone time reading and thinking. Then I set constraints. First, text selection. Then format, concept, timeline, budget, intended audience — where will this end up in the world? What work does it need to do? Then, design. This typically starts with stick-figure lettering in my shop log, lots of thumbnail sketches. Once I have an idea for what typeface I want, I start pulling type and physically composing. Then, the proofing process, which includes a lot of back and forth with myself and/or whomever I’m collaborating with, always revisiting the original text. Whenever I get stuck in the design process, I go back to the poem and hang out with the language itself. Once the design is finalized, comes the sweet (and of course, sometimes swearing) part — production. Printing is the cherry on top of a long process of getting ready.

I know I’m done when I can walk away, and come back, and the piece feels solid, like it already existed without me. If it feels like I found it, then I know it’s strong enough to be in the world on its own.

What or who has currently been inspiring you? Why and how have they shaped your own work?

I’m really interested in writing as a mark-making process and vice versa. I’m fascinated too by what gets left out, sometimes more so than what’s left in. How things are framed. Some artists I’m lately inspired by are Corita Kent, Gloria Petyarre, Bouthayna Al Muftah, and Jo Olive. I’m fascinated by the movement in their work and the interactions between writing, painting, and print. Also Rick Griffith; the way he navigates language and design, writing and printmaking, ethics and policy, challenges my mind and bolsters my heart. And I love anything Maria Popova writes — her far flung observations and closely held connotations let my heart bubble up to the moment of whatever I’m doing.

I think the common thread here is that I feel an exuberant sense of permission, of possibility, of deep consideration, and great joy when I experience these artist’s work. I’m constantly trying to unlock that sense of freedom in my own work from within tight constraints. I really want to end up at the same feeling I have on a mountain top, or reading a damn fine poem for the first time.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Poetry Unbound is out now with new episodes every Monday and Friday during the season. Subscribe today so you don’t miss an episode — on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Overcast, or wherever you find your podcasts.