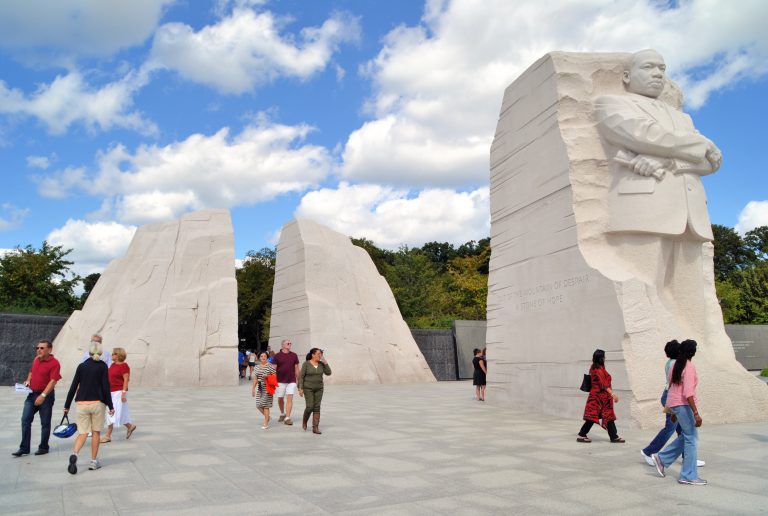

Image by Jonathan Pellgen.

Not Perfect, But Heroic: Humanizing Our Heroes

I first heard of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a little girl watching CNN with my parents. Living at that time in Nigeria, the most populous black nation, I did not know much about racism. “Black” did not occur to me as being my identity or social category, and so I could only relate to Martin Luther King as a distant American hero.

On moving to Canada and finding that February (in addition to being my birth month) was also Black History Month, I became interested in learning more. Now that I live in the United States and in closer proximity to racial issues, I have become much more connected to that historical narrative. I am also very aware of the self-offering of people like Martin Luther King who made freedom possible for people just like me.

Late last year, I read Marshall Frady‘s biography of Martin Luther King in which I noticed a marked difference between the man and popular depictions of him. The Martin Luther King I had imagined before reading the biography was a man of strong, unbending convictions — a towering, convincing, comported person, a born leader who was ready to die for his cause.

The Martin Luther King I came to know from the biography was a complicated man in his personal and external life. He felt thrown into a story he was both dedicated to and often conflicted about. He despaired often. He sometimes questioned the reasonableness of his non-violent approach in the face of opposition. He felt a strong sense of responsibility, if not guilt, for the lives that had been lost to the struggle. His personal life and habits were also not what one might associate with the stereotypical preacher, especially one whose rhetoric drew so strongly from his spirituality.

Considering these sorts of conflicts in the life of Martin Luther King, Marshall Frady writes that rather than “diminish the splendor of such figures, they lend them a far grander human meaning than their eventual, depthless pop exaltations.”

He adds:

“While evil can wear the most civil and sensible and respectably rectitudinous demeanor, good can seem blunderous and uncertain, shockingly wayward, woefully flawed…And what the full-bodied reality of King should finally tell us beyond all the awe and celebration of him, is how mysteriously mixed, in what torturously complicated forms, our moral heroes — our prophets actually come to us.”

It is often said that we prefer our heroes dead; we flatten them out and exalt them to epic proportions, comfortably worshipping them and keeping them at arm’s length. If we saw them for what they were, would we be able to handle their truly radical ideas? Would we be able to handle the fact they they were human just like us? What excuse would we have then, not to live heroically ourselves?

Our heroes — not their “pop exaltations” — were not perfect and yet they shaped history. We, too, do not need to be perfect to do the heroic. We need not be flat. Or boring. We need not be ideal role models. We need not have ideas that sit well with everyone. We can be complex, contradictory, conflicted, and yet still be beautiful, gifted, and extraordinary.

We are allowed to be humans that somehow keep going in the face of our own conflicted selves, our opposition, and our failure. Judging by the stories of our heroes, that seems to be all it really takes to be a hero.