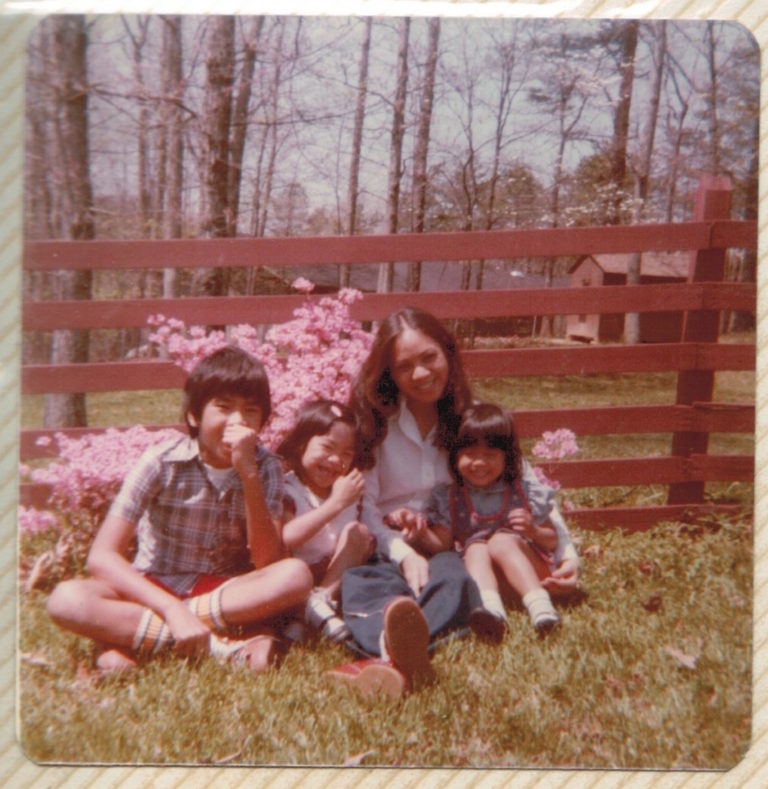

Image by John Cary, © All Rights Reserved.

The Paradox of Motherhood

Becoming a mother, for me, has been a profound experience of paradox.

On the one hand, I’ve never felt so linked to the rest of humanity. When I birthed my baby girl a year and half ago, I became a member of one of the largest, most powerful demographic groups on the planet: mothers. (This is not, of course, to suggest that only those who give birth to children are mothers, just that this was the “path in” for me.) While so much separates me from other mothers, there is this sacred something that we have in common, this awareness of the fragility and fierceness of humanity (another paradox), this knowing that everyone on earth is someone’s child. I feel that commonality viscerally when I talk to another mother, like something has been restructured within both of us. There’s an ineffable recognition there.

On the other hand, I’ve never felt so myopic. This was most acute when I was in the endless early days of nursing. I would sit, boppy curled around my waist like a new body part, and obsess about my baby and myself. When did she last eat? For how long? Is she burping enough? Will she ever sleep longer than two hours? Will I ever sleep longer than two hours? Who is this unrecognizable woman I have become? Will I ever feel like myself again?

I emerged from the “baby cave” long ago, and yet, I still feel like my world is not quite as big, my consciousness not quite as vast, as it used to be. Part of this is pragmatic. It takes a lot of energy and attention to make sure a largely defenseless little creature grows into a person. I spend a lot of my days chasing after a toddler now, guiding her away from electrical outlets and dog crap, holding her hands as she learns to climb stairs, naming every last object in the universe so that one day these words will spill from her own mouth. I look up and out less, as I am so often looking down at her, making sure she survives the drunken, epiphany-a-second, emotional rollercoaster that is toddlerhood.

I’m not talking about “helicopter parenting” or “intensive parenting,” either. Truth be told, for an avid reader, I don’t read many parenting books. I find that when I’m not with her, I don’t want to be reading a less interesting, more abstract version of her in books. I want to be reading about faraway places and social transformation and total fiction and learning about her live and in real time, following my mostly decent instincts about what she needs and when. I actually have little idea if she’s hitting her developmental milestones, as defined by the experts; every new skill seems like a small miracle to me, whenever it arrives.

The myopic feeling is less about parenting style and more about scope of possibility. There is a part of my brain that my daughter now claims. As far as I can tell, it can never and will never be turned off again. It can be dulled for periods of time, my interest in people and things other than her foregrounded. But she’s always there.

When she’s not there in the flesh, she’s an undeniable apparition, a force, a feeling. I make no sizable decision without her in mind. I imagine no future where she isn’t central. I walk through the world with her wellbeing as my compass, as much or more than my own.

Maybe it’s partly a result of the fact that I didn’t become a mother until I was 34, but I find the immutable fact of her startling. On November 12, 2013, I was an individual who intertwined and untangled myself from other humans at will. Sometimes with a sense of great difficulty, sometimes with a sense of deep pleasure, but always with a sense of agency. On November 13, 2013, I became something else.

The lines of my individuality blur. The scope of my vision expands and contracts, again and again, ad infinitum. I’ve heard the idea that having a child is like having your heart walk around, outside of your body. For me, this doesn’t quite capture it. It’s more circulatory than that — perhaps the blood is a better metaphor though I don’t know exactly how to describe what it does “outside of the body.”

Then again, it’s not even a metaphor. A pregnant woman’s plasma volume increases by an average of about 1250 ml, a little under 50% of the average non-pregnant volume. That goes down again after the baby is born, but the sense that the very thing that pumps through your veins has been altered, expanded, complicated, well, that never really goes away. Or at least it hasn’t for me.

In those early days I asked myself: will I ever feel like myself again? The answer, it turns out, is no. In the most universal and specific way possible — no.