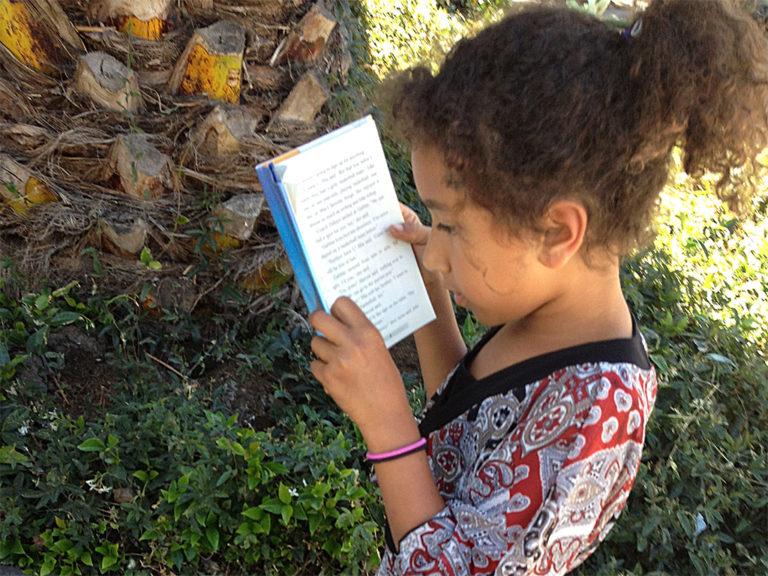

The author's daughter Stella reading while walking. Image by Mia Birdsong, © All Rights Reserved.

Two Rules for My Daughter’s Library

When my daughter was born, I decided there would be two rules for the books I would choose for her:

1. They had to tell a story well.

2. No white people.

Why? Because I was going to raise this little Black girl to believe herself beautiful, capable, and deserving, with a grounded sense of who she was and where she came from. I thought back to my own experience of not seeing myself in the world, particularly my early childhood literary memories — Harold and his purple crayon, the hat seller and his caps, Max with his wild things. Few girls had adventures on those pages and no one was Black. Later Ramon Quimby, Nancy Drew, and many Judy Blume books corrected the gender invisibility, but still… no one was Black.

I was a senior in high school before I read a book by a Black author. Richard Wright’s Black Boy. It wasn’t even assigned to us; I chose it for my AP English class. Along with Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, that book cracked open a window of understanding in my mind through which I glimpsed both a history and future much broader than my education has suggested up until that point.

The next year I went to college and became a Black studies major, not because I thought it would help me forge a lucrative career but because I had to learn about my people, and by extension, myself. The subsequent four years flung those windows open, profoundly reshaping my sense of self. I felt unbound and full of new possibility knowing that I was part of something so beautiful, so fierce, and so much bigger than I’d known until then.

So I decided to try make it different for my kid. I wanted to front load her experience with a full spectrum of brown and Black folks to mitigate the future onslaught of ubiquitous whiteness. I wanted her first experiences of story and representations of the outside world to be filled with people of color, particularly people whom she could imagine being. So I focused on her books.

Of course all children should be exposed to a wide range of people, experiences, and cultures including white people, but I knew my daughter would get books from other people who didn’t know rule #2. And soon enough she’d have the opportunity to choose her own books and inevitably (like, for real, it was literally unavoidable) she’d be reading plenty of books featuring white characters.

Finding books featuring people of color was hard. According to a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, between 2005, the year my daughter was born, and 2014 only 10 percent of children’s books published were about people of color. I found us there in the crowd shots, a token in the classroom, or maybe the spunky best friend just left of center stage. When I did find us featured, we couldn’t play baseball unless we were integrating the league. We couldn’t do our hair unless we loved our hair. We couldn’t have dinner with our family unless we were celebrating a cultural tradition. Books about people of color just being people are particularly rare.

I spent hours combing through Amazon and our local library’s online database. I sifted all the way through to the end of my searches where the obscure, out-of-print books are. And I found the gems: Lucille Clifton’s series about a boy called Everett Anderson; Ntozake Shange’s collaboration with my favorite illustrator Kadir Nelson in Ellington Was Not a Street; the tall tale Thunder Rose; the adventurous, super free-range Aki and the Fox; the sweet Into My Mother’s Arms.

I don’t want to overstate the impact of my experiment on my daughter. There are lots of other intentional and lucky variables in her life. She sees herself in the world in a way I didn’t at her age. She loves her skin, her hair, and her history, but it’s her ability to embrace the present and fantasize wildly about the future that makes me smile with pride and relief.

I asked her the other day what difference she thought my scheme had made for her. She was quiet and thoughtful before saying, “That’s a really hard question, Mama, because I’m just me and I don’t know anything else.”

No declaration of identity, no screed on race. She just seems free and limitless, like a kid.