Baratunde Thurston

How to Be a Social Creative

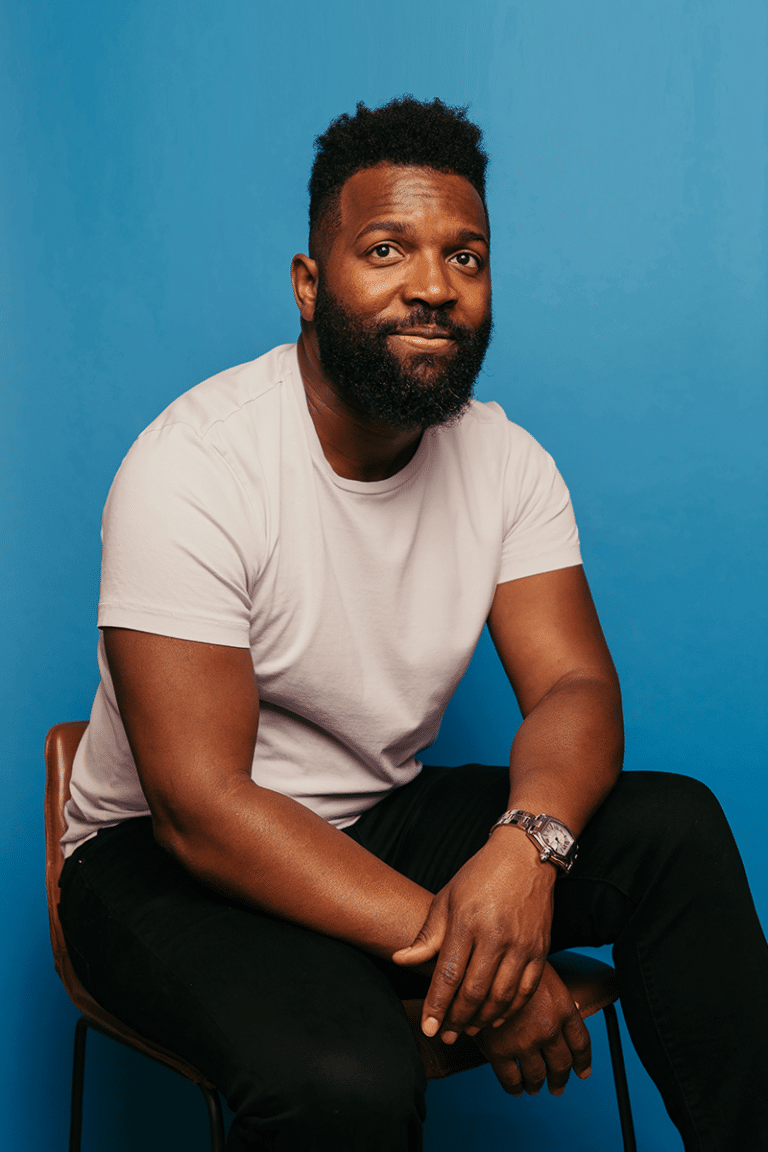

Baratunde Thurston is a comedian, writer, and media entrepreneur. He has eyes open to the contradictions, strangeness, and beauty of being human. He looks for learning happening even amidst our hardest cultural tangles. And he intertwines all of this, innovatively and searchingly, with his lifelong joy in the natural world.

The kaleidoscopic view of life and love and the world that is Baratunde’s builds and builds in this conversation Krista had with him around the edges of the 2023 Aspen Ideas Festival — towards an exuberant glimpse of how we can all be more fully human and socially creative.

Image by Erik Carter, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

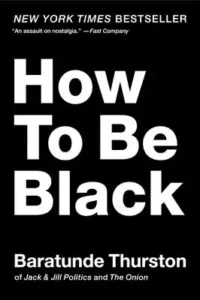

Baratunde Thurston hosts the fascinating PBS series America Outdoors, his latest adventure. He's been Director of Digital at The Onion, produced The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, and advised on digital strategy at The White House. He's a founding partner of the media start-up Puck, and creator and host of the podcast How To Citizen. He's the author of several books, including How To Be Black.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: Baratunde Thurston is a social creative — comedian, writer, media entrepreneur. In all of that, I so admire how he befriends the reality of what it means to be alive now. He operates with eyes open to the contradictions, strangeness, and beauty of being human. He attends in a generative way, seeing better possibilities already unfolding, in the histories and stories we tell about ourselves and others. He sees revelation and learning happening even amidst our hardest tangles. And also — so fittingly in my mind to the time we inhabit — Baratunde intertwines all of this with his lifelong joy in the natural world. This comes vividly through in how he has hosted the innovative and searching PBS series, America Outdoors.

The kaleidoscopic view of life and love and the world that is Baratunde’s builds and builds in this conversation as much as any I’ve ever had — towards a wise and exuberant glimpse of how we can all be more fully human and socially creative.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Baratunde’s late mother Arnita Thurston is a north star of his story — a woman who did not graduate from college but went from distributing Yellow Pages to becoming a computer programmer. At the 2023 Aspen Ideas Festival, he and I found each other in a small recording studio, with a few of our producers, where many podcasts were being made.

Baratunde Thurston: It sounds like we’re entering some kind of teleportation room. See you on the other side.

[laughter]

Producer: I’m just going to steal my laptop.

Tippett: Oh that’s yours?

Producer: The one charging.

Thurston: If it’s yours you can’t steal it.

[laughter]

Thurston: I’m going to go farther. Let’s airplane this.

Tippett: So, you were born — Baratunde, welcome — you were born in 1977, which is a straightforward fact, and then just about everything else about you isn’t. [laughter] So I want to lay that down. Otherwise, it’s been so much fun digging into you, and there’s just such eclecticism in your pursuits and there are geological layers of history and your family history, and you straddle so many worlds in your body and in your experience. With that in mind, I’m curious about this question I’d like to pursue about how you would begin to talk about the spiritual foundations and formations for this way of living, being in the background of your childhood, however you would define that word — spiritual — now.

Thurston: The spiritual foundations of all that I am becoming, and its eclecticism and straddling, these roads definitely go back to my mother, Arnita Lorraine Thurston.

Tippett: Boy, is she amazing.

Thurston: What a force. Spiritual, cool word. I have a tangible, technical experience of that as a child. I was baptized Catholic. We went to this Catholic church though not just for the teachings, but for the community and the support. It was Sacred Heart Catholic Church in the Mount Pleasant Columbia Heights area of Washington, DC. We ended up there by my best understanding in part because that church had a school that my older sister Belinda had attended, and at some point of my sister being at that school, my mother couldn’t afford it. Instead of removing my sister from the school, she offered to work there or they offered her the opportunity to work there. They came to some arrangement and my mom labored in part at the school to cover this tuition. It was just important for her that a child of hers had more than just the basic education.

My mother was a seeker. I think she was looking for healing. She was looking for some explanation of what she had been through in terms of the difficulties in her life. She was always interested in evolution of herself and connecting with the higher power. So that also meant that we went to the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers. And we would go to Friends’ meeting houses every Sunday where you sit facing each other and there is no priest, and there is no incense, and there’s no Sunday school, at least not the ones that we had gone to, and you just sit in quiet reflection.

So I had that as a base. This is all pre-10-years-old, all of these experiences. And then my mother was getting into Buddhism, and we would go to Buddhist temples, and Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō and I’m there chanting. [laughs]

Tippett: So the eclecticism started early in every aspect of your life.

Thurston: Maybe the spirituality is the explanation for it. I’ve never used that lens to try to understand myself. But that brings me to, I think, the landing point on, at least the start of our conversation, which was my mom took me outside a lot. And to experience nature. When we lived in the city our block didn’t have a ton of nature. We technically had a front yard, but it was not well-kept. There was a lot of bricks and broken glass and some hedges. We weren’t growing things there, but I was a community garden member, and there was Rock Creek Park a few blocks away, and we would go to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, take these epic road trips, and sit around the fire with a park ranger out in Kitty Hawk and hear ghost stories. So that also connected me to something that feels very spiritual.

Tippett: You know what it feels to me also is very whole, which is also something that you’re about. It’s also a word I’m using a lot, so we’ll probably circle back to that.

Thurston: Yeah, let’s do that.

Tippett: I want to obviously get to the outdoors, but before we move on from spiritual underpinnings…

Thurston: [laughter] Let’s keep going, keep digging. Let’s see what we find.

Tippett: …so I actually feel like — You said in an interview with The Guardian, “Comedy is my weapon for this soul.”

Thurston: Did I say that?

Tippett: Yeah, you did.

Thurston: Wow.

Tippett: It’s good.

Thurston: That’s good. [laughs]

Tippett: So here’s the thing. So first of all, let me just lay this out. You’ve done so many cool things. Trevor Noah, Obama White House, Puck, PBS, How To Citizen, but the thing I got most excited about that I didn’t know was that you were Director of Digital for The Onion.

Thurston: Yes, I was.

Tippett: It feels to me the way you talk about — and it’s mostly that I’ve seen you being drawn up by other people on this — with comedy is, well, you quote sometimes Dick Gregory, a comedian, civil rights leader, a “man has two ways out in life —laughing or crying. There’s more hope in laughing.” It feels to me like there is a spiritual aspect to humor, comedy — comedy isn’t really quite a big enough word that, in a way, it’s a way of moving through the world for you and actually metabolizing precisely what is unfunny.

Thurston: Huh, yes, metabolizing is a great word. I’ve often thought of myself as ingesting as much of the world as I can and processing it and trying to release it in a healthier form for me — because just taking all that in is actually very poisonous — and for others to try to make sense of things, make meaning out of it.

And so I remember as a child, we had left D.C. because while the neighborhood was home, it felt less and less safe to call it that because of what every city in this country went through with crack cocaine and policing and gang and drug violence. So my mother sold this house that she worked really, really hard to get her hands on. We moved out to a still Black neighborhood, but a suburban one, suburban-ish: Takoma Park. And I remember watching a documentary special about Black comedy, and it was called something like A Laugh, A Tear. And I watched this with a a lot of attention. As a younger person in that first neighborhood, I also remember us listening to so much comedy. We listened to Whoopi Goldberg albums on cassette. We listened to Redd Foxx, a little bit on LP. I wasn’t really allowed to dive into that. I watched Eddie Murphy: Delirious before I probably should have.

Tippett: Gosh, there’s a lot. [laughs]

Thurston: We listened to Bill Cosby. We listened to Garrison Keillor. Lake Wobegon was a big part of my entertainment because: no cable television. And I remember watching this special and seeing all these comedians talk about processing pain through humor. Personal pain, collective, communal pain, and that’s where I first found that quote that you just cited. To make sense of the world and our place in it is probably a spiritual quest, and comedy, humor has definitely helped me try to do that.

Tippett: I think of you as a social creative, which is a way — I’m really wanting to use that language also…

Thurston: Thank you.

Tippett: …and also not just activism. We have activists, and then there’s nothing kind of…

Thurston: Thank you for that because many of the words I’ve stumbled upon to try to describe myself, they’re insufficient.

Tippett: They’re insufficient. I was thinking about this while I was reading about you, I feel like you and I are comrades in different corners of our world. Choosing what we’re looking at and looking for in the world, and desiring to amplify what is good and beautiful without denying what is not. Finding what there is to laugh at and delight in, and also the good and beautiful possibilities even when they’re not as loud and evident and fully formed as what is breaking.

So I talk about this often as the generative narrative of our time. And then there’s this gap, and we’re both in media, and there’s this gap between that reality of how people can be and are, especially in the places they inhabit in real lives, and then the stories we tell ourselves about the world and about humanity in general. That gap is there even in the way you tell the story of your life. Somewhere you wrote, somewhere you wrote, “Yes, I grew up in the’ inner city’ … and I survived D.C.’s Drug Wars. Yes, my father was absent — he was shot … in those same Drug Wars.” But it’s also true that you graduated from Sidwell Friends High School, and also you write about D.C. — that D.C. was also a place of joy for you…

Thurston: Very much.

Tippett: …and all of that is true.

Thurston: We started with this word: whole. I think so many times, I know so many times I want a thing to be good. I want to be good. So much of what has animated and motivated me from that same childhood where we started is I want my mom to think I’m good, I want my grades to be good, I want to be a good son and a good person. And so if I stray from that, then I’m bad. I don’t want to be bad. How do I get back into the “good” category? It’s a place that I want to occupy, and I don’t want to visit that other place. That’s bad people and bad things.

Many, many folks have discovered this, but it seems to take each of us, our own self-discovery of it: we’re all of it, and it’s okay to have gone through a horrible thing and find some good in it. That helps us metabolize the horrible thing, and that might even be necessary to face — I actually think I’d remove the might. It is necessary to face the bad thing, but not stay stuck in that either. I think we can just know the horror and know the bad and then think, “Well, we’re in that category now. Now we’re in the bad category. Now we’re in the unjust and wrong category, and I want to get to the right category.” It’s like, “Oh, my goodness. We’re just messy people, man.”

So D.C. was wrong in many ways. My childhood was wrong. There were things that occurred that shouldn’t have, and I was so lucky. My mom’s childhood was way more wrong than mine. My sister’s childhood was way more wrong than mine, but whatever happened in those moments for them created them, created my relationship with them, puts me here with you today to be able to reflect on it, and I can still move with joy and so did they. My sister continues to, and my mom did. She, with all of her trauma of sexual abuse and so much that happened in her childhood and the political activities, she saw a possibility and she exposed me to that as well and didn’t just live in the category of victim or hurt. She explored the category of healing and empowered, and I got to see that.

So yeah, I love D.C. I love the D.C. I came from, even as it was a painful place to be. And I really recognize how lucky I was too because there are people who are statistically quite similar to me, who had statistically very deviant outcomes from my own, and that’s not just because I’m intelligent or clever or special. It’s random. It’s very random.

Tippett: You did have that great mom, too.

Thurston: I did, and for me, that wasn’t random. That was a thumb on the scale. [laughs]

[music: “Discovery Harbor” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: So you said you just got back from Utah, and was that for PBS, for America Outdoors?

Thurston: That was for America Outdoors, yeah.

Tippett: It also seems to me — and I don’t know if you knew this before you started doing this series or if it’s something you’ve discovered — but that what is happening in the natural world and the natural landscape and also the human life that exists on it and with it, is itself a phenomenal place to uncover and see these generative stories that are often hidden from our imagination.

Thurston: Everything we need to know is right around us. It’s under our feet. It’s literally in the air we breathe. The idea of stands of trees, we’re in Aspen as we speak right now, and an Aspen tree is up to thousands of trees all from one mother tree, genetically identical. A lot has been written and explored about the underground networks and mutual aid society of fungi and tree roots and salmon and how they all interact with each other with the nitrogen and boom, boom, boom.

So I did not enter the process with America Outdoors looking for that. Making that show was a fortuitous event that passed before me and I said, “That’s different. Let’s double click on that. Let’s get back outside,” because I had been so wrapped up in the network world of computation and computing and digital, and it really strayed from some of those early experiences that my mom helped introduce me to.

So it was a homecoming, and I’m still that kid, and that kid came back out to play, but then I’ve got 30 years plus now of all the other things I’ve seen. So it is really powerful to look to nature as precedent, as teacher, as inspiration, as family member, and relate as a peer to another animal, another life form, and realize, “Oh, we can learn. This is a whole school right here.”

Here’s a specific story that happened very recently in the making of the show. I’m on the Rio Grande in New Mexico with a man named Louie Hena. He’s a member of two different tribe slash nations. One is Zuni, the other I can’t recall at this moment. We’re rolling down this river and he’s pointing out all the beautiful landscapes and telling me some of his childhood experience. But I asked him, “When you see this river, what do you see?”

He said, “I see a kitchen. I see a pantry. This is where I get my food. I see a medicine cabinet. This is where I get healing and the vitamin D. Why are you taking pills? Just go outside. I see a hospital. I’ve been in the hospital. That’s not a place of healing. I get worse there, the white walls, fluorescent lights buzzing, machines beeping, frenzy. This is the place I come to heal. I see a playground. I see a church. This is where I get in touch with the creator and with my ancestors.”

I didn’t sign up to hear that from Louie, but I got it, and I’m so happy to learn slash remember that. It’s a great teacher and a great partner.

Tippett: You started the series in Death Valley, and just that name — [laughter] First of all, what you discovered there, but just the fact that that’s the name, which completely shapes and restricts our imagination. That tells the whole story, really, about what we do with the stories. Could you just talk a little bit about that?

Thurston: Absolutely. So the show emerged in my life as a possibility in early 2020. I was actually on a very high-tech expedition to Silicon Valley to give a talk at a big tech company about something. I did my interview slash audition remotely to host this series, then called Outdoor America. They were like, “Why do you want to do this?” and I was like, “Well, let me tell you about my childhood. And I want to reconnect with that kid, and I think it’d be powerful for folks to see a techie, nerdy, political Black dude out there in the trees and on the rivers trying stuff and loving it or not, but experiencing it nonetheless, experiencing it nonetheless.”

The production was delayed by COVID shutdowns. And I drove to the place most of us know as Death Valley from L.A., and everyone else in our own vehicle, socially distanced. To go to a place called Death Valley when most of us were still in our homes away from each other, mourning the loss of people we know or don’t know, but see a growing unnecessarily large number was hard.

The other thing that was happening on my drive — we’re within the blast radius of the summer of 2020 with the so-called racial reckoning and the conflagrations around that, and Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd, and Breonna, all that, and I’m a Black dude driving by himself on the highway to get, allegedly, to a place that’s very important, but who’s going to — I remember my wife being really concerned about this. I remember calling my friend that I went to college, one of my lifelong best friends back in Boston. I just needed to talk to someone.

The last time I had been alone on a California highway going a distance, I got pulled over by the cops and I called my mom. And I was like, “Yeah, I just want you to know I’m in a situation. The cops coming,” and just had her there with me through it. This was quite a long time ago. The cop was great. He was a pro. We made jokes. He actually — this is so funny. [laughs] He saw my self-published comedy book on the passenger seat and he says, “Oh, you’re a comedian.” He lit up, and I was like, “Yeah.” He’s like, “Tell me a joke.” I’m like, “I charge for that, sir. [laughs] You waive my ticket, maybe we’ll work something out here,” and he let me off with a warning. He’s like, “That was funny. You’re good.”

So Death Valley is in my future as I navigate these roads with the stories of police brutality and unnecessary use of state power. That was a hard trip. That was a really hard trip. And the way we made that episode was harder than any other single one. That season was hard, but we didn’t know each other either as a cast, as a crew, and support folks. So much shaped me from that, but the biggest one when we talk about the story of Death Valley as a name is meeting with the people who lived there since before colonizers gave it that name.

Tippett: And the name is?

Thurston: Timbisha.

Tippett: Also, the Death Valley name, it’s because…

Thurston: Yeah, so we — I speak as “we” because I’m an American and I inherit this history, too. We gave it that name because a group of explorers — European explorers — didn’t know how to handle themselves in these conditions. And they got into a tough spot and they ran out of supplies, and some of them didn’t make it and they said, “This shall now be known as Death Valley.” It’s labeling something based on a small group of people’s failure for all of us. So we are entering “incompetent valley.” We are entering “didn’t prepare for the circumstances valley.” We are entering “didn’t listen to the locals valley.” [laughs] There are other ways we could have interpreted their experience, but they had the authority to put the pin on the map and put the fonts in the name, and therefore it is: Death Valley National Park.

Tippett: And it’s beautiful.

Thurston: And it is full of life. It is full of life. So there’s another story underneath of the headline. The one is literal. Death Valley is kind of silly because there’s so much life there. I encountered wildflowers. I encountered humans. I encountered amazing birds and little tadpoles in the stream from the waterfall. Also, I found a waterfall in the desert with the help of some of the people we had on the show. So it’s literally not Death Valley.

Then at another level, the people who lived there long before these particular explorers stumbled upon it, tried to cross it, they call it Timbisha, and they call themselves Timbisha, and that’s a story. The people are the land, and the land is the people, and there’s no separation there. So to try to cross and conquer and fail and impugn this whole space with your failure is a dramatic casting aside. To call it “death” is a total separation from the lives we all are a part of. And then to separate that land from the people who had been one with it for so long — through our government policies, through our broken treaties, through all the history of Indigenous displacement…

Tippett: And yet who live there.

Thurston: Yes, and the best part — oh, my goodness, Krista, it’s like a third level because we can acknowledge, “Okay. There’s life in Death Valley.” “Life Blooms” is what we actually called that episode. It blooms there in the people who’ve always been there and still remain there. And what’s beautiful about that particular nation tribe is they reclaimed land from the U.S. federal government in the designation of a national park. It’s never been undone before to get land back to Indigenous people before they got some of it back, and that’s a story of life too.

Tippett: Blackness is a theme of yours, and I would say even a lens that you apply and…

Thurston: Yes, very dark shades. [laughs]

Tippett: …did you also know before you got into this how this exploration and working with the natural world and these unexpected communities you found everywhere…

Thurston: I knew some.

Tippett: …how it would illuminate this?

Thurston: When we started with America Outdoors, I came with some intention and some specific stories that I knew I wanted to see, and one of them I said, “We’re putting Black surfers in the show.” I just knew it.

Tippett: So you knew about the Black surfers.

Thurston: I knew about the Black surfers. I told them about the Black surfers [laughs] because as a New York City resident for a big window of my life, 2007 to 2019 — I was doing a talk in Mexico about social media to a group. I did a lot of those talks back then. This was a surfing group. One of the ways that I have a prerequisite for talking to people is to know them. I’m not just going to give the prescripted thing. This is a dialogue, and I’ll read the program, I’ll taste the food beforehand so I can make a joke about the food or the temperature, just relate. I’m like, “There is no way I’m getting on the stage talking to a group of surfing industry legends and experts and retailers and business folk and I’ve never been surfing in my life.” So I took a surfing lesson at that conference in Cabo, Mexico, and I fell in love, and I got back to New York City, and I bought a surfboard in Dumbo.

First of all, there was a surfboard shop in Dumbo in Brooklyn. That’s a whole thing. And I walked back to my apartment at Fort Greene with this giant thing slung under my arm, and I learned about the Rockaways, Rockaway Beach, and Long Beach next to it, just to the east on Long Island, and I took the train. I got on the A train with my surfboard, and people looking at me like I’m just — There’s a story of who’s the surfer, there’s a story of what New Yorkers do. There’s so many myths being busted right here.

I remember, Krista, walking through Brooklyn with my surfboard between train stations and, “Oh, it’s that brother with the surfboard. Oh, there he goes, there he goes!” [laughs] like a mythological creature, but the beauty that…

Tippett: Did you call it? “Wakanda on the Wave.”

Thurston: Wakanda on the — Yes. When I hung out with the…

Tippett: With the Black surfers?

Thurston: …with the Black surfing group in Los Angeles that we featured in the show, Color the Water is their name. Making the show widely representative and changing some of the story of who does what in the outdoors, who are these spaces for, and how we can show up in them, that was a mission and remains.

[music: “Pacific Time by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I love your book, How To Be Black.

Thurston: Thank you.

Tippett: I meant to bring it with me, and I was rushing out because I was late and I didn’t, but when did you write that? 2013?

Thurston: The book, we published it on February 1st. Well, technically, January 31st, 2012.

Tippett: 2012.

Thurston: Just in time for Black History Month. I wanted to juice the sales.

Tippett: [laughs] I know. So that’s the thing. I wonder if you’ve looked back lately because it’s about really serious things and it’s really lighthearted. One of the things I found myself feeling is sad. I don’t know. I just want to talk to you about this world we’re living in now. I don’t even know where to start.

Thurston: I’m sorry. Actually, questions about the world we’re living in are off-limits. I forgot. My PR person should have told you that. I don’t do that.

Tippett: Well, I’m going to push it. One thing we can’t do right now is get lighthearted when we wander into race, talking about race. It made me hope that we can get back there, but just making fun of each other, honestly. You start it by — and you’re making fun of white people — so Congratulations — this is not the exact words: You bought this book because it’s Black History Month and this is the book you chose.

Thurston: The opening to that book is a playful invitation to engage in this conversation.

Tippett: That’s it.

Thurston: For anybody who might pick it up. I said things like, “If you’re white, this book is not going to actually make you Black, and there will be no refunds. You can consider it a reparations down payment. For Black people, we can always improve our skills. Continuing education is available to all of us. We all got something to learn, so nobody knows the whole thing.” And the whole book is a feint, right, there’s no way to be Black. But titling it that was an absurd invitation to poke at a possibility and uncover some painful stuff in the process, too.

I really enjoyed — I was in a very special place when I wrote that book. I was five years having been at The Onion at the time. I was surrounded by top-notch comedy and transgression to some degree, just enough of rule-breaking and boldness in terms of how you might communicate a point. But I also knew my intentions, and that is one of the results of them.

Tippett: I think what you said, it is an invitation. The whole book is an invitation, and it’s playful, and it’s a serious invitation, and it’s playful. So I live in Minneapolis where George Floyd died, and I just remember feeling in those weeks after like I didn’t really know how the planets could keep spinning.

Thurston: Yeah, how dare they.

Tippett: Then in those years of the pandemic — and that wasn’t the only thing we were called to, we also had to ask what is essential and what is non-essential before that, and the things we don’t reward were most essential. So I felt like there were these callings that were placed before us. Then of course, I’m just riffing and you can push back, but the protests were really important, but they weren’t the work. So I kept thinking, “Okay. We’re going to get on the other side of this, and then we’ll just pick these callings up one by one. And they all go together.” And now I’m still kind of waiting. I wonder how you are seeing that and maybe you see things unfolding or how are you experiencing — you could call it this post-George Floyd world, but that’s not, that’s too simple.

Thurston: We updated our Instagram pages with black squares, and that fixed about 60% of the problem. Then with the remaining 40%, we had declarations and pledges from companies. So that covers another 35%. We have a 5% left to really finally formally resolve the question of race in America. I think we could do it with maybe one more conversation. [laughter]

Tippett: Which you will facilitate.

Thurston: Yes, with a playful invitation. I think about this. Gosh, I write with Puck.

Tippett: Which is so great. I love Puck.

Thurston: Thank you. When I started there, it was two years ago almost, I had this series, After the Tide, I called it.

Tippett: Yes, I read those.

Thurston: I felt like the tide was coming in with George Floyd as an unnecessary but powerful figure in that moment. And then it’s receded, and what do we see when the water goes back out? Are we changed? Are we committed? In places we are. In many places, we’re not. It’s a top-down and bottom-up thing. One of the things that I see has to do with just the experience of Black people and how we handle all this stuff.

I’ve spent a lot of my gaze outwardly focused. I’m like, “How will the white people receive us? How can we help them be better so that we can breathe?” I have belatedly come to a pretty common conclusion for people who are involved in this work that that ain’t the path. You don’t get freedom by hoping someone else gives you permission to be free, and my freedom can’t be dependent on your enlightenment.

However, there’s in that an opportunity to reframe it and think about what freedom really means, what liberty and justice for all, how you operationalize that, and some of that’s very internal. Some of that is my own sense of what brings me joy, where do I take moments, how do I reset after an annoying-up-to-traumatic experience regarding my racial identity in this particular land and the community of folks I have to be a part of that, and share that with. That’s liberating to find that loophole in the game. [laughs]

Tippett: The loophole is not dependent on anybody else changing, even though you still want that to happen.

Thurston: Absolutely. Then I’m also thinking — We just opened a museum in this country in South Carolina. The name escapes me, but it is honoring a receiving point and a trading post for enslaved Africans. And it is very local. It has global impact, and it got done in this environment. From what I’ve seen of it online, they are very honest about some of this brutal history, and they are very celebratory about the resilience and the community and the creativity so that we do them both. We are whole in a story like that.

I recently was in Madison, Wisconsin, and visited in the last days of the exhibit at the Chazen Museum of Art, “Remancipation.” Such a great process. They took the “Emancipation Group,” this sculpture that Thomas Ball made after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. It depicts an always tall Abraham Lincoln in long coat and got the three-piece, and hair nicely did, and he’s holding the Emancipation Proclamation and he’s got his hand extended out benevolently over a shirtless, pantless loin cloth African descendant, formerly enslaved person, still bound in the shackles but they’re broken, and looking up sort of pleadingly to the great white savior. This was memorialized in Boston, it’s still memorialized in Washington, D.C.. They did an artistic intervention with a group called the Mass Consortium with Sanford Biggers, and they decided, “Okay. We don’t just want to destroy this old statue. We want to re-contextualize it. What is emancipation? What does it look like?”

I am so excited about that, and that’s where I prefer to point my attention, and that’s where I like to live, and the things I found through How To Citizen and the whole network of folks who are reinterpreting what it means to belong to each other.

So in terms of the post-2020, there’s a lot of disappointment. Now, promises made, promises broken. And — I almost said but, even I get stuck into the binary — and there’s been a lot of revelation, a lot of progress and process, and I see it in my small self when I go out on a shoot with America Outdoors and I find all kinds of people. I’m on ranches with the Trumpiest of Trumpers. I’m out there blasting shotguns with very Second Amendment people, and I’m adjacent to or near the reservation or on the reservation with Indigenous folk, and I’m with the Black and immigrants in new refugee communities. Like, oh, my goodness!

Tippett: Appalachia, also.

Thurston: Yeah, and in Appalachia, which has adaptive use of the outdoors for people with disabilities, which has regenerative agriculture where we build a whole different economic relationship with our land, which has so much. There’s another story possible for every story we ingest that we don’t like, and it doesn’t require fiction to know that story.

Tippett: It just requires a fuller telling.

Thurston: Yes, and a premise of my life is that we are the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. I’m here in part to help, to nudge, to cajole, to do some strike-throughs and some live doc edits on improving that story of us and trying to find and make one that serves us all better. I think that work has moved forward. There is resistance to it.

Tippett: So what you just said and the contrast, I don’t want to talk about critical race theory or all of that.

Thurston: She said the words. [laughter] Ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding. Here come the Storm Troopers.

Tippett: Yeah, no, but to me it feels like a total deflection and distraction from this real fuller story.

Thurston: Yes, it is those things. I have what I think is useful, maybe a little novel, maybe a little surprising. It’s not humorous, but it’s some new approach. I don’t know if it’s enough to help move us past this particular stage of stuckness in our story, but I’ll offer hopefully a compressed version of it here.

My mother was the greatest mother of all time. You have some evidence of this, some experience of this indirectly through my life and through your research and my telling, and all those tellings are true. She was all those things. And, there are things that I’ve learned about myself and how I show up in relationships, and how I behave. I’m not happy with that, and they’re restricting me from becoming more of the person and man that I want to be, and my mom’s responsible for some of that, too. And that’s a really difficult — it has been and had been a very difficult thing for me to acknowledge. I just had knee-jerk defensive, a typical Black boy-mom relationship, “Don’t you talk about my mama.” Including to myself, “Hey, Baratunde, don’t you talk about my mama. Not like that. You are there to praise her, respect her, appreciate her. That’s how you love her through all those things.” And, that’s not enough.

So through COVID, with all the time alone, I found some time. I was forced. I was given some time. I was force-fed time to contend with some of this, and I came to the radical conclusion that my mother was a person, a whole person with elements of everything and that some of her limitations affected me, and they weren’t her fault. It didn’t make her bad, which made her real, and she couldn’t teach things that she wasn’t taught. So that was liberating for the story of my mom that I put in the book that you love so much. There’s no nuance about Arnita Lorraine Thurston in How To Be Black.

Tippett: No, there’s not. [laughter]

Thurston: She is Saint Arnita.

Tippett: She is.

Thurston: All good. There’s no reference to arguments because we didn’t have any. Because I was just making — I didn’t want to make her hard life harder. So I’m trying to accommodate constantly as a little child bearing the weight of all this adult stuff. And that idea that love is knowing emerged for me through my relationship with my mother long after she has passed. But when we know the whole of a person, then we can love them. For those of us who are in really loving relationships, we know that that is true. Our spouses, our children, our siblings, our friends, we know some dirt, we know some shameful things, we know some embarrassing things that they’re not going to advertise on their public social media profiles. And that creates an intimacy and a vulnerability. So: let’s know, let’s love America.

And I get the fear of, “I don’t want you teaching my kid to hate themselves.” I just want your kid to know so they can love. And we should teach and raise our young people and ourselves with the objective of love. And that requires some pain. I think what’s often missing is I can say something like that and it can make some logical sense — and it has worked tangibly, in some experiences. It’s like, “Oh, yeah, on the other side of that pain, there is more freedom.” I feel better about my relationship with my mother now that I’m more honest about it.

Tippett: For everyone, there’s more freedom for everyone.

Thurston: Exactly, for everyone. You’re free of your little story that says all you can be is this. I’m free of the subjugatory story. The subjugated and the subjugator are liberated by that. But in the middle, we can acknowledge the pain. We can acknowledge, this is a hard thing for some folks. It was painful for me to reckon with my mom not being Saint Arnita, and I cried and I punched walls and it was horrible, and I moved through it with help. But I moved through it. There’s no going around it.

So I have empathy for some of the reaction not for the people profiting and monetizing off of acting the damn fool and ginning up a false sense of controversy because they get ahead for it, but there’s a true emotion there that’s a real fear.

Tippett: There’s a caricature of what it would be that then is manipulative and then completely derails precisely the process that you just talked about, which we all go through in our lives. If we are in a love, intimate relationships, and they’re going to grow, that happens.

Thurston: Yes. We have, as many in the psychological world talk: rupture and repair. And the repair is part of what makes the relationship stronger. You can’t repair without rupture. You can’t heal — which everybody wants to skip to healing in America — without acknowledgment of harm. That acknowledgment is going to cause some rupture for some people. How we repair that, how we acknowledge, that can make us stronger or we can just stay stuck on rupture, on rupture, on rupture and never get around to the repair.

[music: “Inessential” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: So what you have just been taking us through is How To Citizen.

Thurston: In some ways, yes.

Tippett: Interestingly, that’s where we were going to go next.

Thurston: Now, I see why you’re the GOAT. Okay. I didn’t see that. Sometimes I see it coming. I didn’t see that one coming.

[laughter]

Tippett: I was going to ask you, which is a verb, where does the L-word — love — come into this? But you’ve already gone there.

Thurston: “Citizen” as a verb is something that emerged in many ways, for me at least, from a lot of the life we’ve touched on, a lot of the mom that we’ve loved on, and even from the comedy world that I was a part of where I saw a lot of, and participated in a lot of really great storytelling about how broken everything is. It’s some of the greatest, the things that get passed around on social: “so and so destroys,” so there’s like violence in comedy, or just explain and breaking down why we’re so broken down. And I wanted to move forward a bit and tell the story of the mending work that’s happening and finding the people who I personally knew. I have an eclectic network based on the life I’ve lived and the people I’ve associated with, that said everything I’m seeing on the news doesn’t really match up to what I’m experiencing through my own relationships. They kind of stop at the first half of the story.

Then our ways of addressing some of the brokenness are presented to us as a very limited set of choices. We can buy things, we can vote for other people to fix the things, and then we can protest the people that we voted for when that didn’t fix the thing or the purchases didn’t solve the problem. So that was a lot of the energy going into the formation of How To Citizen. Then with my wife, Elizabeth, during COVID, she came into it and workshopped that [laughs] and helped us ground this in a series of actual principles, not just that that’s a more vague, high-level poetry that I was coming into this with and a gut feeling. But in between there, there’s an articulation of what does that actually mean and what counts and what doesn’t count. So we call them the “four principles” or the “four pillars.” That was another birth out of my Death Valley COVID.

Tippett: There’s such a strange — Well, it’s just this polarized way, it’s the hyper-reactive, polarized time we inhabit, which I think I also don’t think we stop to just acknowledge that what we’ve just been through and that our bodies are aroused and overstimulated and fear just — We lived in fear however conscious or unconscious we were, but every single one of us. Obviously, there’s a spectrum. So that just amped everything up, amped up this quickness to leap, to acting angry when actually you’re terrified.

I want to just ask you about this because I come up against this, you’ve used the word “healing,” “mending.” There’s often this sense in public cultural spaces that justice and healing are incompatible things, that you can’t even talk about healing until there’s justice. And then where does love come into all of that? There’s this complex mix. I just wonder how you think about those things together in this work of How To Citizen.

Thurston: Let me lay out briefly what these four pillars are, because I think that will help us find a way into love, justice, and healing as simultaneous things we can experience. I think they unlock each other, this circle.

So we have these four things: “To citizen” is to show up. We just assume there’s something for us to do, and we don’t always know what that is, but we have an orientation toward, “Put me in. I don’t have to lead, but I have to be a part of the thing.”

Number two: “To citizen” is to invest in relationships with yourself, with others, and with the planet around you. We have inherited a story of separation of all these things, and they’re actually all one. The quantum physicist will tell you that really in a short sentence. So that myth busted. [laughs] There’s a…

Tippett: Yeah, but we inherit this fiction that we have internalized and believed.

Thurston: We do, and it’s in our bodies, and it’s in our stories, and it’s in our laws, and it’s in our economics. All those things we made, we can remake and unmake. That’s the beauty of it. It’s all fiction, actually. So we just do a different fiction. So relationships at the center of this.

“To citizen” is to understand power and all the different ways we have it. Eric Lou, I call him one of our founding guests, founder of Citizen University. He says: power is just the ability to get somebody to do what you want them to do.” And we have different ways of doing that. Physical force is obvious. Money, especially in this society, is pretty obvious. Ideas, sharing them. You’re very powerful, Krista. Putting our attention on something, we give power to what we give attention to, and we can choose, within default settings and design incentives, but we have the power to choose what we give our power to with our attention.

Fourth of four of these principles is: “To citizen” is to value the collective. We do all these things out of a sense of collective self-interest, not just personal, individual self-interest. Valerie Kaur was our very first guest for How To Citizen. She is a spiritual leader in the Sikh community, S-I-K-H, for those who don’t know. She is a civil rights lawyer. She’s an activist. She leads a movement called The Revolutionary Love Project.

Tippett: I listened to that, too.

Thurston: Just the fact that you started our discussion with spirituality and we started our podcast project with Valerie, there’s a lot of people out there doing civic engagement work…

Tippett: That’s right.

Thurston: …and we didn’t knock on their doors. I knew about Valerie. I saw this beautiful poem that she presented in, what for many of us was a very dark moment after the 2016 election. She was on stage with Reverend William Barber, and she said: what if the darkness that we’re in “is not the darkness of the tomb but the darkness of the womb,” and we can use this as an opportunity for new birth while we honor the death that we are experiencing? That still moves me, but so does her call to see a stranger as a part of ourselves we do not yet know, and that’s the premise of her book, See No Stranger. We are each other.

Love is at the center of that. Knowing each other, in my amateur conception of self-discovered elements of love, seeing ourselves as each other in Valerie’s conception, which is inspired by King and Gandhi’s perception, and Audre Lorde and so many other people, that helps give life to this possibility even in the midst of death.

So when we are in this moment of justice, healing, love, they support each other. We have this tool, this process available to us, of restorative justice. Restoration is healing. We restore wetlands. We restore the financial health of a business. We restore our bodies through medicine and meditation and all the tools at our disposal. We can restore the relationship of one who has transgressed in society and restore their relationship and role in that society through a process. It’s not just a switch.

Tippett: No, there’s a rigor to it.

Thurston: There’s a rigor to it. There’s honoring of the act of violation that happened. There’s honoring of the humanity of the violator. There’s seeing them as more than just that transgression, that violation, seeing them as possibility still to be among and with us that we are worth being a part of, and that they are a part of us. That’s all kind of love stuff in there. [laughs] So there is a lot of that orientation in the How To Citizen work. We are finding people who exhibit these pillars and who have some deep love for their place. They’re committed to their city. There’s a project in Seattle with architects who are trying to address this housing challenge we have in our nation. They didn’t wait for the city council. They didn’t wait for the developers. They got an ADU-designed, additional dwelling unit, and they said, “Raise your hand if you want to put one of these in your yard to help our unhoused neighbors be housed neighbors,” and so many people are doing that. There’s citizens’ assemblies.

Tippett: See, I hadn’t heard — Why have I not heard about that?

Thurston: Because you haven’t listened enough to our podcasts. No, that’s Ego-tunde speaking. [laughs] No, but because we have a system that creates incentives to tell a vast minority of who we are and we have opportunity to expand that. That’s part of what I’m so motivated to do.

Tippett: So great. This is a little bit of a detour, but we’ll circle back to the end in a few minutes. I said I think of you as a social creative.

Thurston: You did say that.

Tippett: I actually sent something to my son, who’s 25, that you said in another interview and I did not write down where you said this, which felt to me like good counsel on becoming a social creative. He doesn’t always respond to my texts. He wrote me right back and he said, “Love this.” He’s 25 and he’s asking all these questions you ask when you’re 25: “What am I going to do with my life?”

Anyway, so you said this, “If you’re just starting out, try a lot of things; and if you’re going to try five things, make sure one of them is something you never thought you’d be interested in. Exposure has been the biggest lesson in my life. Not everything pans out into a job, a gig, money, accolades, or respect, but there’s usually something worth learning, even in the pursuit of something you don’t like. The greatest lever in my life has been exposure to variety. In the world that we have created for ourselves, nothing is stable; nothing stands still” — and every 25-year-old knows that right now — “You can’t just know a thing, master it, and then rest on your ass. You could be great at something [today] that won’t exist tomorrow. Look at print journalism or the cable TV model: things are crumbling around us, and new things are emerging. There’s a level of flexibility that should be built into whatever it is that you’re doing, and constant exposure to things that are new, different, occasionally distasteful, or not obviously interesting is important.”

I love that. Because this is also getting at how you’re crafting your life, your presence in the world. And, this approach to it also is going to make you a better citizen.

Thurston: Yeah, yeah, and it’s also nature. Exposure to variety is very valuable in the natural world when it comes to our immune strength…

Tippett: Vitality, yes.

Thurston: … boosted by exposure to varieties of all kinds of organisms, plant life. The metaphors scale up and they scale down. They’re fractal, in the adrienne maree brown view of the world, not just hers, but one that she’s very good at talking about. I have not thought about that in a long time. Thanks for finding it. I don’t remember where I said it either, but I do remember saying it. So ChatGPT didn’t make that up.

Tippett: No. We’ll talk about that next.

Thurston: It’s our opportunity in this instance, in this level of the simulation on this timeline in America right now is to embrace the invitation to expose ourselves to difference in a generative way, in a loving way, in a collaborative way so that we can live together better. I didn’t use the word democracy in there, by the way.

Tippett: No.

Thurston: It’s a technical term. It’s a label for a type of technology perhaps, but…

Tippett: You said democracy is a relational exercise, though. This is flexing that relational muscle.

Thurston: Exactly, and sometimes it’s distasteful. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable. We have established and doubled down on systems that ultimately come down to maximizing comfort. The algorithms that feed us more of what we just bought, that encourage us to watch more of what we’ve just seen, and to meet people like the ones we already know. That is not exposing us to variety, that is not helping us live together because we live in a world of so much difference and increasing collision of that difference without the practice of navigating it, of sharing power, of contesting power in a generative fashion.

Disagreement isn’t the enemy. What’s our process for moving through it? Can people still feel heard through that process such that even though they didn’t get what they want, they have faith in the process, AKA the institution. Everybody’s right here talking about, “We want to increase faith in the institution.” Well, the institution has to earn that faith with a process that we can have faith in. You don’t just demand fealty. It’s very authoritarian. It’s very old-world story. That’s what John Alexander called The Subject Story, and then we have The Consumer Story they talked about. We just buy it. We buy all our needs. A transaction solves it.

The Citizen Story — which I believe and John writes about, — that we are increasingly in, says we encourage the participation, the facilitation, the working through and with process that allows us to live together and adapt. America’s so funny. We’re such a funny, funny country in terms of our potential and how we’ve held ourselves back from really realizing it. Fascinating experiment to have a true multiracial democracy. We still haven’t done it, but we can do it.

Now, the trick of it is, a lot of nations have existed due to honoring a single autocrat or authority, praying to the same God, having the same shade of skin and the same language. We don’t have any of that. We have decreasing abilities to say that that’s what we are. We have borders-ish, but that’s a fiction. We have texts. We have documents. We have values. We have opportunities to recommit to each other for new reasons that we haven’t even come up with yet. We can look back and be originalists, or we can be creators together of what and why we want to be together. The practice at doing that, even with our current differences and instability, will only serve us more. Because more instability is coming.

The water’s rising, the temperature’s going up. More people of difference will emerge on this land, and more people we thought were one thing will emerge as not quite that. Gender is a spectrum. We’re dealing with — we are multiplying, even with the people we thought we knew, more difference. So we need to practice these muscles. We need to work this out.

Tippett: Not only that though, we have to practice them together alongside each other…

Thurston: Exactly. Yes.

Tippett: …because this way of living, this moment to be alive, where we have to actually befriend uncertainty…

Thurston: Boom.

Tippett: …because that’s what we’ve got, but that is so hard in a human body. That’s why I feel like it’s really useful to say, “How do I exercise these muscles?” but this is not an individual — This is also not about us doing it in that fiction of separation.

Thurston: No. We…

Tippett: It’s about us accompanying each other in this.

Thurston: Yes. We can, on paper, have extraordinary wealth and resources and opportunity, and if we have all of those things alone, we are miserable. We can, on paper, have no money, no job, no housing, limited food, and when we have those things and go through that experience together, we feel complete and loved and like we belong. We feel rich. Going through it together is the only way to go through it at all. Otherwise, we can’t make it on our own.

Tippett: We’re back to wholeness too because we’re not whole. We can’t be whole on our own.

Thurston: We are. We are. So the idea of how we deal with any of this is how we deal with all of it. The change in difference in economic opportunities wrought by technology, the change in difference in the truth and the understanding of who we have been historically, the change in difference of the number of languages spoken, the change in difference of the borders not through act of legislation, but through act of ecological change through climate change. Waters coming and going, fires are coming and going, and that’s going to put pressure. And how we handle that pressure is who we are. Who do we want to be? Let’s practice that. Let’s get ready. It’s already here. Let’s go.

Tippett: And those are the human questions. Those are the elemental questions…

Thurston: We ain’t the first.

Tippett: …but we’re evolving those questions.

Thurston: Mm, you got me all fired up.

Tippett: Well, good. You got me fired up too. There are other things — You know what? I want to read you something you wrote, you said about yourself, “I’d love to have part of my legacy be that I was compassionate; that I exuded joy, warmth, confidence, and competence; and that I was more than talk—I was a man of substance.” And I just want to say to you: good job. You’ve done that. You’re there.

Thurston: Oh, thank you. Thank you, Krista.

Tippett: You have a lot of time left, I think.

Thurston: I hope so. We never know.

Tippett: We never know, but you’re…

Thurston: I’m doing what I can within my control to have that time and to make the best use of it. I think we all are invited citizening all the stuff we’ve been talking about. There’s the macro way of thinking about it that involves commissions and blue ribbons and all this kind of stuff. There’s this sphere of influence that we have with the people directly in our lives and the community groups and businesses and teams. And then there’s within ourselves as well. So we’ve had a really, really, really opening, there were tears, there was jokes, there was laughs, and what’s the story of me that I want? For you listening right now, what’s the story of you in the context of the cells that comprise you and the history that brought you here, and the future that’s unfolding before you and in the context of who else you belong to in a human sense, in a broader sense of life itself?

I’m trying to remind myself constantly of our power, my power to change that story and to do it in community with others, even community of my selves, you know, the people that brought me here, the community of the Arnitas, most of whom I wasn’t willing to see when she was alive.

Tippett: I just remember there’s a picture in your book, a photograph of your mother at your Harvard graduation hugging you. It’s so beautiful. What did she say to you? “We did it.”

Thurston: “We did it.” She said, “We did it.” I was like, “Lady, I took the tests. But yes, I understand your point.” [laughter] The metaphor. She was like, “It was a metaphor.” Literally, I showed up in Boston.

Tippett: Okay, but she was just saying what you just said to me. [laughter]

Thurston: I know, I know, I know. No, I literally remember when she said that, and I had this moment, I had both responses. I had a, “What you talking about, lady?” and then I had a, “Oh, dummy. Come on, man. Yeah, we did it,” and “we” is not me and her.

Tippett: No.

Thurston: It’s not me, her, and Belinda, my sister. We did do that, but it is Arnold, my father, who’s not around anymore; and his parents, Leon and Dora; and my mom’s parents, Homer and Lorraine; and the people who begat them and the community that poured into them simultaneous to my mom’s life, the Africans who introduced her to the diaspora and got her all in the Afrocentric activism. We did it. The people who wrote the checks for me to go to that school that weren’t in the family, the scholarship committee, they did it too. The U.S. government has a little piece of that. The D.C. government has a little — D.C. public schools did it. The Boys and Girls Club did it. The D.C. Youth Orchestra program did it. So we are always at every moment a culmination of “we.”

[music: “Scratcher” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Okay. We did it. We did it.

Thurston: Holy cannoli. Is the sun still up?

[music: “Scratcher” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Among his many adventures, Baratunde Thurston is executive producer and host of the PBS television series America Outdoors, currently in its second season. He created and hosts the podcast How To Citizen with Baratunde. And he is a founding partner of the media startup Puck. He’s also author of several books, including How To Be Black.

Special thanks this week to Gabe Chenoweth and everyone else at the Aspen Ideas Festival.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Juliette Dallas-Feeney, and Annisa Hale.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.