Desmond Tutu, Natalie Batalha, Eckhart Tolle, et al.

‘Becoming Wise’ With Tools for the Art of Living

Over the years, listeners have asked for short-form distillations of On Being — something to listen to while making a cup of tea. Our podcast Becoming Wise is this offering, designed to help you reset your day and replenish your sense of yourself and the world, ten minutes at a time. A taste of the new season, curated from hundreds of big conversations Krista has had with wise and graceful lives — including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, astronomer Natalie Batalha, and spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle.

Guests

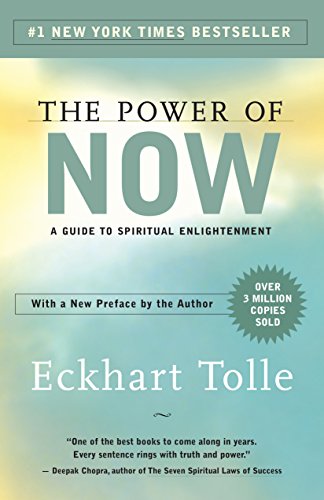

Eckhart Tolle is a spiritual teacher and the best-selling author of A New Earth and The Power of Now.

Ruby Sales is the founder and director of The Spirit House Project in Atlanta. She is included in an oral history of the Civil Rights Movement at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Rami Nashashibi is founder and executive director of the Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) in Chicago. He was named a MacArthur fellow in 2017 and an Opus Prize laureate in 2018.

Natalie Batalha is a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. She served as the project scientist for NASA's Kepler mission from 2011 to 2017.

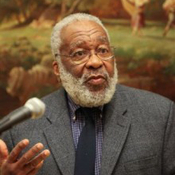

Vincent Harding was chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. He authored the magnificent book Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement and the essay “Is America Possible?” He died in 2014.

Desmond Tutu was an Anglican archbishop emeritus of Cape Town, South Africa and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He has written numerous books for adults and children — including The Rainbow People of God, No Future without Forgiveness, Made for Goodness, and, together with his good friend the Dalai Lama, The Book of Joy.

Sharon Salzberg is one of the original three young Americans who traveled to India in the 1960s and ‘70s and introduced Buddhist meditation into mainstream Western culture. She is a globally renowned meditation teacher and co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. Her books include Real Happiness, Lovingkindness, and most recently, Real Change: Mindfulness To Heal Ourselves and the World.

Robert Thurman is the first American to be ordained a Tibetan Buddhist monk by the Dalai Lama. He is president of Tibet House U.S., and was a professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University for 30 years. His many books include Inner Revolution and the book he co-wrote with Sharon Salzberg, Love Your Enemies. In 2021, he published Wisdom Is Bliss: Four Friendly Fun Facts That Can Change Your Life.

James Martin is a Jesuit priest and editor at large of America magazine. His books include The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything, Between Heaven and Mirth: Why Joy, Humor, and Laughter are at the Heart of the Spiritual Life, and, most recently, Building a Bridge.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: I’ve had hundreds of big conversations on this show, and my conversation partners share wisdom I carry with me wherever I go. Across the years, people have asked for shorter-form distillations — something you can listen to while you make your cup of coffee or tea and something shareable. The Becoming Wise podcast is this offering, and we’re now launching its second season. This hour, a taste — nine wise and graceful lives, moments of discovery, and tools for the art of living.

Sharon Salzberg: It’s very hard to see love as a force, as a power rather than as a weakness. But that is its reality.

Desmond Tutu: Human beings, they can leave you speechless by the horrible things they do, but they can also leave you speechless with the incredible things.

[music: “Sun Will Set” by Zoë Keating]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

We begin with Eckhart Tolle. I interviewed him in the early years of the show. He began to gain attention as a spiritual teacher with his 1997 book, The Power of Now. Millions of people around the world have found pragmatic tools in his vision that fundamentally complicates the notion, “I think, therefore I am.”

Ms. Tippett: You tell this story in A New Earth about — you experienced a woman talking to herself on the tube train — tell that story — caught in her thoughts. And then you came to understand that you had some of the same problems.

Mr. Tolle: Yes, I would sometimes see her on the train, and she would continuously talk to herself or to an imaginary person in a very angry voice, continuously complaining — ”And then he did this to me, then he said, and I said” — and then, “How dare he tell me this” — and I watched in amazement. How can anybody be so insane and still apparently have a job? Because she would catch the subway every morning.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] She was going somewhere, right.

Mr. Tolle: One day, I was washing my hands in the bathroom, and I thought, “My God. Her voice, she never stops talking.” And I suddenly realized, well, I do that, too, except that I don’t do it out loud. And then I thought, “I hope I don’t end up like her,” and somebody next to me looked at me, and I suddenly realized in shock that I had actually said these words aloud, just like her. I said, “I hope I don’t end up like her.” [laughs]

I realized my mind was as incessantly active as hers. Our only difference was that my thought was mostly based on feeling sorry for myself. It was depressed thinking. Her patterns were fueled by anger. It took years before I finally was able to really step out of the stream of thinking and realize there is a place inside me that is far more powerful than the continuous mental noise with which for many, many years I had been completely identified, just like that woman.

Ms. Tippett: So what happened to you when you were 29 to finally, really jolt you out of that?

Mr. Tolle: I was in the depths of depression, and I lived in anxiety about my life and my problems and my future. One night I woke up again feeling this sense of dread, and a phrase came into my head, which said, “I can’t live with myself any longer. I can’t live with myself any longer.”

Suddenly I was able to stand back and look at that phrase, and I thought, oh, that is strange. Who am I, and who is the self I cannot live with? Because there must be two of me here if that phrase is correct. There are two of me. The “I” was there, and the “me” that I couldn’t live with actually was the continuous mental noise, the stream of thinking that considered life and that considered myself as a problem.

Ms. Tippett: I wonder if some aspect of that is that when you are fully alive and fully present, even if in a very powerful way — even if your presence is powerful — there’s something about knowing your place in the scheme of things, being aware of how complex and large everything around you is.

Mr. Tolle: Yes, and the vastness of it all and the compulsion to continuously interpret whatever you are experiencing at any given moment — that is no longer there. There’s great freedom in not compulsively interpreting other people, situations, and so on, not imposing all these judgments. That’s another word for it: imposing thinking continuously on the world, which is so alive and so fresh and new at every moment. So, yes, the mind is beautiful, the ability to think is a great thing, and it does not mean you fall below thinking when you are open to the present moment in the state of …

Ms. Tippett: Or that you turn your mind off, right?

Mr. Tolle: Yes. What we are talking about here is a state of alert attention to what is, where compulsive thinking no longer operates. This means you rise above thinking to a large extent in your life, where you can face life without the interference of the mind — still being able to use the mind when it’s needed but not being used by it.

[music: “Miss You” by Trentemøller]

Ms. Tippett: My favorite book by Eckhart Tolle is The Power of Now. He’s also the author of the wildly bestselling A New Earth.

The Civil Rights marches of the 1960s started in churches and ended in churches. The movement had a preacher as leader. The spirituals and hymns of that movement became hymns of the nation. The Civil Rights elder Ruby Sales opens up what it was to be a teenage participant in that work of social shift, including the impatience she had with religion and how she circled back, through her experiences of the movement and of life, to a sense of the deep reason for inner life and religious groundings.

Ms. Tippett: One thing you’ve said — and you’ve likened yourself to the Black Lives Matter — a lot of the kids who are involved in that today — that you were not especially religious, that you had this grounding in church, but you said that a lot of you used to complain when there had to be these obligatory prayers before everything started.

Ruby Sales: It was downright embarrassing.

[laughter]

You couldn’t go to a mass meeting without these people always praying. And it was like, my God, do we have to do this? But when I first went on my first demonstration, I was really kind of naïve, unsophisticated, a peasant who had been bred on black folk religion and who really believed I was a part of the Pepsi generation, who really believed that right was right, and it would win out. So I went on my first demonstration, and I’m embarrassed to say this, but we were surrounded by horses and state troopers who wouldn’t let us go to the bathroom, and I kept looking up at the sky, waiting for the Exodus story to happen to me. [laughs] And it didn’t happen. I expected God to appear and some chariot to open up in the sky, because I couldn’t imagine that we were so right, and God would be so wrong. In my 17-year-old mind, I couldn’t imagine that — I mean, my 16-year-old mind. So I lost religion that day, and I slowly became a Marxist. I became a materialist. If it wasn’t economics, if it wasn’t race, then it didn’t exist. And I thought black folks were religious fanatics. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: So tell us, how did you eventually circle back to the place — or circle to the place, maybe it’s not back — where you went to divinity school, where you started to be a public theologian? And what did that mean?

Ms. Sales: I think the paradox is that even when we think we’ve left home, we never really go anywhere. Although I thought that I was not religious, the truth of the matter is, I was, and I went to church all the time, and that was the Sweet Honey concerts. Bernice Johnson Reagon kept us in church. All of the songs that she sang and all of the music and the God talk that she would do from the stage — she became the preacher for a generation of African-American young people. She herself was the daughter of a preacher who thought that we had left the church, but black folk religion was so deeply ingrained in us that we never really left it. So I carried with me the songs. I carried with me the testimonies. I carried with me the whole notion of right relations. That was the cornerstone of how I imagined justice.

Ms. Tippett: Even when you didn’t feel religious.

Ms. Sales: Right, I really never left. But a defining moment for me happened when I was getting my locks washed, and my locker’s daughter came in one morning, and she had been hustling all night. She had sores on her body. She was just in a state — drugs. Something said to me: Ask her, “Where does it hurt?” And I said, “Shelley, where does it hurt?”

Just that simple question unleashed territory in her that she had never shared with her mother. She talked about having been incested. She talked about all of the things that had happened to her as a child. She literally shared the source of her pain. And I realized in that moment, listening to her and talking with her, that I needed a larger way to do this work, rather than a Marxist, materialist analysis of the human condition.

Also, I was riding down the road one day in Washington, D.C., after having been at a demonstration against the war in Iraq, and suddenly, out of nowhere, I started crying. I realized that God had been with me, even when I hadn’t been with myself. Those moments made me really begin to seek to go back, to really think deeply about black folk religion, and to really want to develop, in a very intentional way, an inner life that had to do with how I lived in the world.

[music: “Give Your Hands to Struggle” Bernice Johnson Reagon]

Ms. Tippett: I have hung on to that question, “Where does it hurt?”, as a spiritual and practical tool so resonant in this era of tumult and social shift.

Ruby Sales is founder and director of The SpiritHouse Project in Atlanta.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with nine wise and graceful lives, a taste of season two of the Becoming Wise podcast.

Rami Nashashibi fills me with hope about how art can make humans visible to each other. He brings a new energy to Islam’s core commitment to beauty and humanity — and to the power of stories to heal and electrify us across geography and generation, culture and faith. He founded the Inner-City Muslim Action Network on Chicago’s South Side, where he also lives with his family.

Ms. Tippett: Talk to me about how you bring the arts into what you do. Here’s one of the big defining sentences on your website — that IMAN works for social justice, delivers a range of social services, and cultivates the arts in urban communities. I want to hear a little bit about how spiritually and practically the arts and justice work together for you.

Rami Nashashibi: For me, that tradition — and while now we host artists from the subcontinent who are performing Qawwali alongside an opera singer, along a spoken-word poet, alongside a traditional hip-hop artist. A lot of that, honestly, started with hip-hop.

Ms. Tippett: You’re really critical of people who condemn hip-hop as part of the decay of culture and ruining our young.

Mr. Nashashibi: Yeah, because I think hip-hop’s origins have been extraordinary, and that’s because there is an aspect of hip-hop culture that was extraordinary in bringing together the most disconnected, the most marginalized and disempowered sectors of urban young people, both in the Bronx and then in other urban centers, and found extraordinarily creative ways of expressing not only a search for a commonality but a common cultural experience that was both universal and particular at the same time. You found for the first time young Latino, black, and white kids in New York coming together around a cultural creation that both allowed them to celebrate their Aztec traditions as well as their shared New York experience. That model, that formula, became global.

The way we gravitated toward it was very organic. It became the most powerful and useful way of bringing together young kids in Chicago who were totally disconnected from one another while still living and sharing the same kind of urban experiences.

For example, one of our first projects we did was on one big side of the wall where there was a well-known graff writer — and graffiti writing is one of the four elements of hip-hop in Chicago. His name was Zore, a Puerto Rican guy. I got a hold of him, and I showed Zore traditional Islamic calligraphy. There’s a verse in the Qur’an that some people have heard. It’s, ‘We created you into nations and tribes so that you may get to know one another, not hate one another,’ and that ‘the most dignified among you is the one with the most consciousness of the divine.’

We used that verse, and I showed him traditional Islamic calligraphy, and it was done in this really ornate, circular style. And he said, “Let’s throw that up on the wall.” And I said, “Yeah, that’d be great.” He said, “But I’m going to make it contextually relevant to urban graffiti,” [laughs]. I said, “That’s fine. You can do whatever you want, Zore, as long as you retain the core elements of this piece.” And he said, “That’s fine, and it’s speaking to me. I see this piece. It’s speaking to me.”

I remember what we did was, literally, we gathered over 250 kids in the neighborhood, and we had this unveiling of it that brought these hip-hop artists together. It was both something that connected; it was relevant; it celebrated a core aspect of Muslim tradition. That was as early as 1995, and since then, we’ve used the art as a way to tell our stories, as a way to connect our stories. The arts have become the real factor for us in both humanizing each other’s stories, connecting our stories, and, I think, revealing to one another the possibilities of what a better world can look like.

[music: “Ether” by Dekko]

Ms. Tippett: Rami Nashashibi was named a MacArthur fellow in 2017 and an Opus Prize laureate in 2018.

What is love? The astronomer Natalie Batalha embodies a planetary sense of what “love” is and means. She has searched the universe for exoplanets, earth-like bodies beyond our solar system that could harbor liquid water and life. She is so warm and joyful as she takes this work into her life as a human on earth.

Ms. Tippett: Here’s a way you’ve written about — just some language you’ve used: “What we observe out there is that nature is creative, prolific, robust.” You also bring words like “love.” It’s not that you’re confusing these things with your science or conflating them, but I sense that this life of discovery that you’re involved in does bring you back to think about something like love differently — that it informs and somehow infuses your thinking about that. Talk to me about that.

Natalie Batalha: Yeah. This has been a surprise to me, actually, that my perspective on love has been so informed by science. But it has. It’s been fundamentally shifted. And then I read other scientists who’ve had the same perspective, and it all makes sense. Carl Sagan’s quote — ”For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.”

Love, this idea, is this moving force. It just permeates our history, our culture. I’ve equated it to this analogy of dark matter — 95 percent of the mass of the universe being something we can’t even see, and yet it moves us. It draws us. It creates galaxies. We’re moving on a current of this gravitational field created by mostly stuff that we can’t see. Science has given me that perspective but also in very logistical, tangible, practical ways. When you study science, you step out of planet Earth. You look back down at this blue sphere, and you see a world with no borders. You see a tiny mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam. You see the expanse of the cosmos, and you realize how small we are and how connected we are and that we are all the same and that what’s good for you has to be good for me.

Ms. Tippett: Was there a moment or did something happen where you first realized you were thinking about love the way you were thinking about dark energy? It’s a really interesting connection. Also, it changes the way you think about love. It is an energy, right? It’s not just a feeling inside you.

Ms. Batalha: Certainly, with my own personal experiences, being middle-aged and having raised four children …

Ms. Tippett: I know. You have four children.

Ms. Batalha: I have four children [laughs] and just going through life and all of life’s challenges and adversity and losing people that we love and all of those things make us think about love. We need to be loved and to love to be happy.

Studying science, you realize the connectedness of all things. We are stardust, and here I am, this bag of stardust, and it took how many billions of years for the atoms that make up my body to come together and make this being that’s able to take a conscious look at the universe. I am the universe, and I’m taking a look at myself through these senses that I have and that is an amazing thing.

Ms. Tippett: For you, that’s such a concrete statement. Somebody else could say that and it might seem a little flaky, but you really know what you’re talking about [laughs]. I mean, you’ve discovered the first rocky planet and things like that. You really know these things.

Ms. Batalha: Yeah. Well, no, that’s a good point. I don’t necessarily mean it in a hippie, flowers-in-my-hair kind of way. It’s easy to say all these fluffy philosophical words that make us all warm and fuzzy, but there are really practical connections. There are things that I do see that are real, that are part of what we’re discovering.

[music: “Repeatedly” by Ametsub]

Ms. Tippett: Natalie Batalha is a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. She served as the project scientist for NASA’s Kepler mission from 2011 to 2017.

Here’s an image I love of the late Vincent Harding, of what we can all be: “Live human signposts.” Vincent Harding himself was a live human signpost, and he remains a mentor to me and countless others. He was a central figure in the Civil Rights Movement, a speechwriter for Martin Luther King Jr. He spent the rest of his life on a project called Veterans of Hope, bringing the wisdom of the movement to young people in hurting places.

Ms. Tippett: There’s a story you tell that is about your conversation, encounter you were having in a hard neighborhood in Boston and a young man named Darryl. Would you tell that story about his image of signposts?

Mr. Harding: What I remember from that story was that a dear young friend of mine, Eugene Rivers, young at that time — I guess Gene’s going to feel old.

Ms. Tippett: Still busy in Boston.

Mr. Harding: Still busy in Boston. I met this young man in Eugene’s apartment, and this young man came up to sit next to me because he wanted to talk in a more personal way. It turned out that he was one of the leaders of the drug-running folks at the time. But what he said to me was that he really felt that one of the reasons why he had gone in the way that he had gone — not trying in any way to excuse himself — was the fact that he, like many other young people, were operating in a situation where they felt it was just very, very dark all around them. And what they needed were, as he put it, some signposts, some lights that would, in other people’s lives, help them…

Ms. Tippett: “Live human signposts,” you wrote.

Mr. Harding: Yes, that would help them to see the possibilities for themselves and will open up possibilities that other people can’t see in any other way except seeing it through human beings who care about them. If we teach young people to run away from the darkness rather than to open up the light in the darkness, to be the candles, the signposts, then we are doing great harm to them and the communities that they have come out of.

Ms. Tippett: I think this word “signpost” and this image of signpost is really important. It’s an important piece of practical vocabulary. What you also tell young people is that they have to find the elders, right? I’ve thought a lot over the years about the teaching in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament that I think has resonance across the traditions of developing eyes to see and ears to hear. I think that is almost a spiritual discipline that the 21st century makes more necessary.

Mr. Harding: That whole idea of discipline is one that, clearly, we have cast aside, except when we’re talking about technological development or military development. It seems to me that we need, again, to recognize that to develop the best humanity, the best spirit, the best community, there needs to be discipline, practices of exploring. How do you do that? How do we work together? How do we talk together in ways that will open up our best capacities and our best gifts?

My own feeling that I try to share again and again, Krista, is that when it comes to creating a multiracial, multiethnic, multireligious, democratic society, we are still a developing nation. We’ve only been really thinking about this for about half a century. But my own deep, deep conviction is that the knowledge, like all knowledge, is available to us if we seek it.

I think that that determination to find a truly democratic society and to create the truly beloved community, those are things that can be available to us if we’re willing to work with each other and work with the universe on developing them. They don’t come free and easy. They are tough, tough tasks for us to take on.

[music: “Voice of My Beautiful Country Suite: IV. My Country ’Tis of Thee” by René Marie]

Ms. Tippett: Vincent Harding taught at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. He authored the magnificent book Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement and the essay “Is America Possible?”

Coming up: Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Sharon Salzberg, Robert Thurman, and Father James Martin. You can subscribe to On Being and to Becoming Wise in all the usual places: iTunes, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or wherever you find your favorite shows.

[music: “Sun Will Set” by Zoë Keating]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Becoming Wise — moments that have stayed with me ever after from 15 years of big conversation about the mystery and art of living.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu is one of our wisest teachers on the territory of reckoning with wrongs from the past that infuse and haunt the present. In the 1990s, he helped galvanize South Africa’s peaceful transition to democracy after decades of white supremacy as the law of that land. He chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, or TRC. Its basic premise was that any person was eligible for amnesty if they would fully confess their crimes. Archbishop Tutu knew that saying “I’m sorry” is one of the hardest things for human beings to do, and he did not expect the human redemption that would surface on this stage.

Ms. Tippett: What did you learn about why, as you said, one of the hardest things for human beings to do is to say, “I’m sorry.” What did you learn about forgiveness three-dimensionally that you didn’t know before?

Archbishop Tutu: One was that I was amazed, first of all, at how powerful an instrument it is, being able to tell your story. You could see in the number of people who for so long had been anonymous, faceless non-entities, just being given the opportunity did something to rehabilitate them. It actually was a healing thing.

We had a black young man who had been blinded by police action in his township, and he came to tell his story. When he finished, one of the TRC panel asked him, “Hey, how do you feel?” And a broad smile broke over his face, and he was still blind, but he said, “You have given me back my eyes.” You felt so humbled that people would feel that that was how the healing for him would have taken place.

One of the things that constantly amazed us was the remarkable magnanimity of people — all people, black, white, Africans, and Americans. Human beings can leave you speechless, really. I mean, they can leave you speechless by the horrible things they do, but they also leave you speechless with the incredible things. We saw so many times people who ought to have been bristling with bitterness and anger, when they meet the perpetrator, actually being able to embrace.

And you were asking about the difficulty. Yes, it is difficult. When we started, we looked at the legislation, and the legislation did not require a perpetrator who applied for amnesty to express even remorse. We were very upset and said, “But why not say they’ve got to say sorry or something?” But we discovered that actually the legislators were a lot smarter — because had they insisted that it was a condition to get amnesty, each time somebody said, “I am sorry. I am very sorry,” we would’ve said, “Ah, he’s just putting that on.”

As it happened, despite the fact that it was not a requirement, when people were applying for amnesty, almost always they would turn to the victims or the survivors or the family of the person who had been killed, and they would turn to them and say, “Please. We know it’s very difficult, but please forgive.” And, as I say, almost always the victims would.

[music: “Senzeni Na?” by Vusi Mahlasela & Harmonious Serenade Choir]

Ms. Tippett: Archbishop Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. He has written numerous books for adults and children, including The Rainbow People of God and, together with his good friend the Dalai Lama, The Book of Joy.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with nine wise and graceful lives, a taste of season two of the Becoming Wise podcast.

[music: “paral.lel” by Near the Parenthesis]

What if we thought of love for our enemies as an act of self-compassion? This is how Robert Thurman and Sharon Salzberg challenge us to frame our anger. They are icons of American Buddhism, and they are joyful, longtime friends.

Ms. Tippett: Something that I think about a lot is that — I think, say, in Christianity, this is often discussed as, there’s the problem of evil or great enemies. And even, maybe, in our culture, we tend to focus on these dramatic, drama-sized enemies: the bully or the catastrophic danger or the murderer. But something that I’m aware of in real life, day to day — I think so much pain and suffering is caused by — I don’t know what I would even call — maybe the near outer enemy, right? Not the villain out there, but the people close to us in workplaces or in families or in friendships. People are vulnerable, and it’s those people who have a power, such a destructive power, to do damage in those circumstances. Where do these beautiful teachings start to speak there?

Ms. Salzberg: I think that’s so crucial. I want to say something about that middle place, learning to stop hating, because the word “love” is so loaded, and what does it mean? Our fear, of course, is that it means something very passive and complacent and — “I’m going to let people hurt me, and I’m going to let them oppress other people, and I’m going to be a doormat.” It’s a very nuanced and subtle quality. It’s very hard to see love as a force, as a power rather than as a weakness. But that is its reality.

So that middle place is very compelling, whether it’s a colleague at work who’s sort of annoying or it’s somebody who disappoints us in the neighborhood or our community or it’s the villain, even, to have some recognition that the way we can be consumed by hatred or even just an obsession, that habit we can have of going over someone’s faults again and again and again — it’s the same list, but we’d like to go over it again a few more times [laughs].

The way we give over so much of our energy to someone else in this negative or destructive way, whether it’s a minor annoyance or a very grave injustice, there’s a way in which we want to be whole. We don’t want to have lost so much of our life’s energy to someone else’s actions or problems. We want that energy to return to us and for us to be able to go on in a more creative, generative way, and that’s the process. That’s why people engage in this process.

Ms. Tippett: So, what do you mean? Tell me the process. Describe that.

Ms. Salzberg: I think first being aware of how it actually feels to be frightened, to be so angry, to be so consumed with somebody else, to be able to see those states, to be able to have a little more distance or space from those states, and …

Ms. Tippett: To just gain some self-awareness about the fact that you are going over and over that and letting it consume you in a way?

Ms. Salzberg: Yeah, exactly. And how it feels because then we want to let go out of the greatest compassion for ourselves, not ’cause we’re trying to be a goody-goody or a certain kind of person or match someone else’s dictum for how we’re supposed to be, but out of the greatest love and compassion for ourselves.

Robert Thurman: There’s a word in Buddhism called “kleshas,” or “kilesa” in Pali, “kleshas” in Sanskrit, which comes from a verb root that means “to twist, something to be twisted.” It’s translated “defilement” or “affliction” by some people. I used to translate it “affliction.” But the best word for it actually is “addiction.” Anger and obsession and lust, these things are said to be addictions, and that immediately gets the point across. In other words, it’s something that people think is helping them because it gives them a momentary relief from something else. But actually, it’s leading them into a worse and worse place where they’re getting more and more dependent and less and less free.

Ms. Tippett: Dependent because the way you’re handling it is then all entangled with the other person?

Mr. Thurman: Yes, right, partly. And partly because you believe when anger comes to you, meaning in the form of an impulse that you have internally, “This is intolerable, that person did this, this is like something.” It’s the inner thought that comes, and it seems to come in a way that is undeniable. You have to act on it. In other words, it takes you over.

That’s where mindfulness can interfere with that, by being aware of how your mind works and realizing that it’s just one impulse and it’s one voice within you. And there’s another questioning voice and an awareness voice that can say, “Well, actually, would this be a good idea to blow your top now?” I always like to say it’s like — otherwise you’re like a TV set that has one channel only and no clicker. If you have the horror show rising up from your solar plexus, then you’re going to have a horror show. Whereas, you can click to the nature show. You can watch the minnows frolicking in the lake in the summer. So I’m saying we are very clickable. We’re very switchable in our moods and minds.

And then the key is, the hopeful thing for some people who like their anger — and some people do like their anger. The hopeful thing is that that energy of heat, kind of like a heat — and actually in Buddhist psychology, anger is connected to intelligence, to analytic and critical intelligence, and so that energy, a strong, powerful energy of heat, force, can be ridden in a different way and can be used to heal yourself. It can be used to develop inner strength and determination, and that is really something much to be ambitious for. That is a great, great goal.

[music: “paral.lel” by Near the Parenthesis]

Ms. Tippett: Robert Thurman’s latest book is Man of Peace, an illustrated biography of the Dalai Lama.

Sharon Salzberg is a meditation teacher and cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection.

Their book together is Love Your Enemies.

Father James Martin is a well-known and beloved Jesuit writer and teacher. He’s followed the calling of the founder of the Jesuit order, St. Ignatius of Loyola, to “find God in all things.” He does so in 21st-century forms, including a wise and witty presence on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. But everyone, Fr. Martin says, has callings, a vocation. This is not something merely for monastics and clergy.

Ms. Tippett: I did not know the part of your story that — because you are known as a religious figure, I did not realize that you studied business in college and worked in corporate finance for GE into your mid-20s, and only then were captured, it seems, by Thomas Merton. Somewhere in one of your books, you pull out this first paragraph of No Man Is an Island. ‘Why do we spend our lives striving to be something that we would never want to be, if only we knew what we wanted? Why do we waste our time doing things, which, if we only stopped to think about them, are just the opposite of what we were made for?’

James Martin: Yeah, that’s the line that changed my life, really. I just thought, well, why? [laughs] Why am I doing that? It felt like he was speaking directly to me. Business is a real vocation for a lot of people, and it just wasn’t for me. I was miserable. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t know how I could find a way out. That sentence, which really was like a thunderbolt, just prompted me to shake things up and ask myself that question. And I always say to young people, what would you want to do if you could do anything that you could do? It’s a very clarifying question for people. Jesus asks people that. What do you want? Kind of understanding your desires. So, yeah, I love that paragraph. I go back to it a lot.

Ms. Tippett: I think something that really runs through all your writing is that callings and vocation, as opposed to a mere career, is not something that’s restricted to monastics.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, absolutely — or priests or sisters or brothers. Everyone has a vocation. The most fundamental vocation is to become the person whom God created. It’s both the person you already are and the person that God calls you to be. And I think we find that out through our desires. What moves us? What touches us? What are we drawn to? Part of that’s career, but only part of it. It’s really who you are called to be, and that’s why that question really spoke to me. A vocation is your deepest identity, and as well, being called to married life or being a lawyer or a teacher.

Ms. Tippett: Being a parent, I think, is a vocation.

Fr. Martin: Absolutely, and a much harder vocation than being a priest, frankly. We don’t get up at 3:00 in the morning for feedings.

Ms. Tippett: Well, you don’t get any of that training. You’re plunged into it.

Fr. Martin: No, we do not.

Ms. Tippett: I love the use of the word “desire” because, again, I think if we do separate — if we do think about vocation or calling in narrow, spiritual terms, which sounds very serious, then we probably wouldn’t use that language of desire — that it has to do with your desires and, in fact, being in touch with them is one kind of compass, but in fact there is a very long and deep philosophical and theological tradition of thinking about desire and calling.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, I’m a Jesuit, and our founder, St. Ignatius, in his classic text, “The Spiritual Exercises,” talked about praying for what you desire and also praying to understand your desires. Because I believe that your deepest desires, the things that you’re drawn to, the person you’re called to be, are really God’s desires for you. How else would God call us to something?

You think of a married couple, that’s the easiest example — they’re drawn to each other. It’s the same in different jobs. It’s the same in religious vocations. But it’s also the same in the person you desire to be. I think we all have an image of the person we want to become — more loving, more open, more free. That’s a call. It’s helping people understand that and recognizing it — to tell them it’s not selfish. Desire, ultimately, is not selfish.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, it’s freeing, and it opens the possibility that this not necessarily is easy but is a process that has joy in it and delight.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, and heartache, sometimes, as we let go of the things that we’re not called to be and the parts of our lives that are keeping us back. This is God calling you. This is a process. It’s ultimately liberating, which is a great message for people.

[music: “Dawn” by Jacob Montague]

Ms. Tippett: Fr. James Martin is editor-at-large of the Jesuit magazine America. His books include The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life, and most recently, Building a Bridge.

What you’ve just heard are nine wise and graceful lives, a taste of season 2 of the Becoming Wise podcast that we’ll be releasing over the next 16 weeks. Reset your day. Replenish your sense of yourself and the world. You can get them all by subscribing to Becoming Wise in all the usual places — iTunes, Spotify, you know the story.

[music: “Brilliant Lies” by Ovum]

Staff: The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Casper ter Kuile, Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, Zack Rose, and Serri Graslie.

Ms. Tippett: The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections