BONUS: A conversation with Lorna Goodison – and the humans behind Poetry Unbound

As part of a celebratory launch party for the new Poetry Unbound book, Pádraig welcomed Lorna Goodison, former Poet Laureate of Jamaica, into a joyful Zoom room of poetry lovers and listeners of the show, old and new. We draw Season 6 to a close with their conversation on themes explored in Lorna’s poem “Reporting Back to Queen Isabella” (one of the 50 featured in the book): poetry as a “made thing”; poetry as a form of travel.

And: Pádraig chats with our wonderful producer and composer Gautam Srikishan on the role of music in the show, with a warm hello from all the humans behind Poetry Unbound. Watch the full, unedited event here.

Find Lorna Goodison’s poem in Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World, and in Season 3 of Poetry Unbound.

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Season 6 — we’ll be back with Season 7 later in 2023. In the meantime, continue your poetry ritual through our weekly Substack newsletter, with more musings and prompts from Pádraig and lively community of conversation in the comments.

Guest

Lorna Goodison is one of the Caribbean's most distinguished contemporary poets. Her work appears in the Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces and her many honors include the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, Americas Region. She is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Supplying Salt and Light, Controlling the Silver, Traveling Mercies, and many more. Her work, translated into many languages, is widely published and anthologized.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Hello everyone. Pádraig here. We’ve just wrapped up season six of Poetry Unbound and we’ll be back in 2023 with another few seasons, and we just launched, as if you didn’t know, the Poetry Unbound book published by Norton in the USA and Canongate everywhere else. And we thought it’d be fantastic for anyone who didn’t get a chance to hear the brilliant Lorna Goodison, as she spoke at the book launch, to have an opportunity to hear her. She reads and talks about her poem “Reporting Back to Queen Isabella.” Enjoy the episode.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lorna is a major figure in world literature, 12 books of poetry and memoirs and literary criticism and short stories. She’s been widely anthologized. She was the poet laureate of Jamaica from 2017 to 2020, and she was awarded the 2019 Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry. And on top of that, she’s won many other awards for her work.

Lorna is one of the reasons I love poetry. I have been reading her work for years, and it has been a thrill to make a Poetry Unbound episode about Lorna’s poem, as well as to write about it, as well as to meet and get to know her and exchange correspondences with Lorna. So Lorna, I’d like to invite you into the Zoom room now, and we look forward to a conversation with you.

Lorna Goodison: So wonderful to be here. Thank you so much, such an honor to be invited by you and I’m just very, very, very honored.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: (Laughs) Well, it’s an honor to know you and to engage with your work, Lorna. We’re gonna talk a little bit about that magnificent poem of yours, “Reporting Back to Queen Isabella,” but I wonder if you’d read it first.

Lorna Goodison: Sure I’d be happy to.

“Reporting back to Queen Isabella.”

“When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

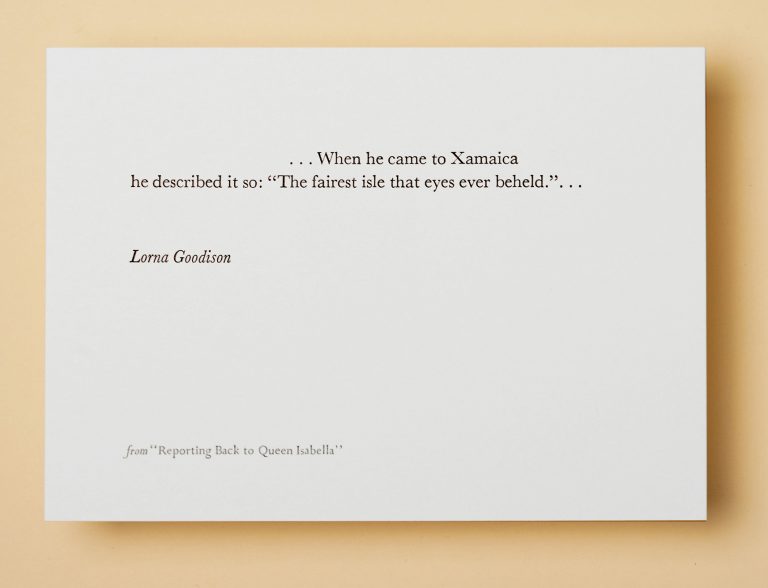

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: ’The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.’

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.”

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Thanks for reading that, Lorna. I love the drama of that poem. Don Cristobal, Christopher Columbus, back in the court of his funder, the Queen of Spain, and all this pageantry that’s happening in it. What was it that—I know that you were doing some explorations around Europe at the time, but what was it that drew you to write that poem?

Lorna Goodison: We would go into these places in Spain and Portugal and, you know, we’d have docents and guides who would explain to us the glorious history of Spain and Portugal. And actually we were with friends, one of whom was Mexican. And every now and again, she’d say to somebody, do you know where this stuff came from? And it would get a little awkward.

But for me, that poem, I think, was born out of what my mother used to call an object lesson, where you’d take an object and you’d build a whole lesson around it. And as a child, I remember her distinctly telling me that when Christopher Columbus returned to Spain to speak with Queen Isabella, he tried to describe to her what Jamaica looked like. And he balled up a big piece of paper and unclenched it to show her that Jamaica’s very mountainous and it’s got mountains and. So I had that object lesson very much in mind when I was doing it.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: How interesting. I’ve always wondered about what that balling up a big sheet of parchment and letting it unclench—part of me wondered, was it an indication of the edge of the world or something? But what you’re saying is that it brings your mother’s story into this and her object lesson.

Lorna Goodison: Yes. I think my mother was a good teacher of little children and she always would find something to sort of illustrate her stories too. And I’ve done that for my students in other places. I say Jamaica’s very mountainous, the Blue Mountains go up to over 7,000 feet, and then if you do that, it shows how mountainous, craggy, and mountainous and filled with valleys, you know, and things it is.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah, yeah. And for you, is that a feature of poetry as well, Lorna, when it comes to the question about an object? Do you pay attention to objects in a poem?

Lorna Goodison: I do because I trained as a painter. I love that definition of a poet as a maker, or as the Scotts say, a “Makar,” that you’re making something like a piece of furniture or something. My mother was a dressmaker. So I think a lot about building a garment when I make a poem, so it’s a very tangible thing, very real to me sometimes, you know?

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah. And what’s this poem’s hunger for you? What does this poem want or need?

Lorna Goodison: Okay. As somebody who has written many poems and many of them—you know Caribbean writers are famous for pushing back, you know, the empire writes back. I didn’t want a polemic, I didn’t want to rage, I wanted to just say something that really came—the poem surfaced as something very quiet.

And I wanted to say things about like the obsession the conquistadors had with gold. I put gold in Queen Isabella’s mouth. Her speech set the standard for, and that’s the one place I use gold. But as we all know those people, they actually said that they’re conquistadors who said, my people have a great hunger that can only be quenched, satisfied by gold.

There are things there that I wanted to say, but I didn’t want to rage, I didn’t want to rant. And I also wanted to say that I guess it was a business, a whole business deal that, the two of them entered into, and the results are, well, you know, we’ve seen what the results are.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Lorna Goodison: But, all of that, those things I wanted to say about profit before people and things like that. And, but I wanted to say it in a very—I didn’t want a rage. Not this time, you know?

Pádraig Ó Tuama: There’s a lot of quietude in the poem. Like I, there’s that list towards the end, that describes all these things. And whenever I read the poem, I always think of the administrators who have to go and count the fields and count the rivers and make the maps. And that the ways within which there’s a quiet highlighting of the entire industry of, of the profit gaze looking at a place that belongs to itself and thinking that it could belong to a European country.

Lorna Goodison: Absolutely. And, one of the things, it is said that the Taíno people who Columbus found when he discovered—he couldn’t discover them, they were there—but, the Spaniards ate so much more than they did. And that’s one of the problems is that they started feeding them, but they just couldn’t, they just ate them out of house and home really. I wanted to put that in there by just saying, you know all this food for Spanish horses, men and cattle.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Oh, interesting. you’ve done something very interesting with the “there we were” in the middle of that poem. It’s a very quiet little revolution in the poem. I wonder if maybe you could read that line again, and then talk a little bit about it.

Lorna Goodison: “There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.”

You had to adopt the administrator’s voice, because I think there were priests, several priests who went along with him, or at least one who kept diaries, you know, very detailed. I’ve read some of them, detailed accounts of what was found there. And as you say, it must be quite a task to be given to number rivers, to say there were hundreds of rivers and 72 planes or whatever.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Lorna Goodison: Straight off that, you know, there’s named, one of the plains there, it’s still there, the Queen of Spain Valley,

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Wow. Okay. You told me once about your usage of the word “massif.” I’ve always loved that.

Lorna Goodison: Yes. And I was very, um, Jamaicans call—wordplay’s such a big part of the Jamaican language and,the masses, M-A-S-S-E-S, became the massives. But that could easily become the massifs, you know? So the masses are the massives and the massifs because we, you know, we’re massive and we’re mountainous.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: (Laughs) That’s a way of speaking of people hiding that kind of, that, that vernacular for speaking of groups of people in topographical language.

Lorna Goodison: Absolutely.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah. What is the effect for you in that hidden, “we” were there and the “massifs,” what is the, like—there’s a way of establishing who was there already and who was also going to be taken there forcibly.

Lorna Goodison: Absolutely. Actually, I was surprised when the poem turned up “There we were.” I wasn’t looking for it. You know, as in many poems you write, what I’ve written, I stepped back at the end of it and I thought, where did that particular thing come from? Because it was not my intention when I set out to write that.

But I just remember this sort of clear way it rose up from, it’s as if it filtered down or something. And it became very clear that at that point I had to say, “there we were.”

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Lorna Goodison: You know, I wasn’t being objective. I wasn’t standing outside the store anymore, just about my story.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: In the midst of the poem not being a polemic, the poem is an assertion, and that assertion comes across really powerfully.

Lorna Goodison: It has to be because, and I think had I not gone to Spain and Portugal, I would not have written the poem in that way. The whole business of the civil service, huge amounts of people were just employed to just keep records and, you know, keep people in check and things like that. And they’re all there, they can show you—you know, they have all these things in these museums of, that was, you know, somebody’s boots spur or something, when they stepped on a Taíno person. No, I made that up, (laughs) but I just thought I wanted to just tap into that somewhere. Maybe if I’d written a longer poem, I could have really gone to town with a catalog of what, how many rivers, how many planes. Maybe I’ll do that.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah. I’ll read that poem too. You were Poet Laureate of Jamaica for three years. What did that show you in terms of people’s interest in poetry and the role of poetry in a country? I’m curious what you felt or learned from that.

Lorna Goodison: Well, I will say that at my age I definitely wanted to resist the urge to take a victory lap. You know, something like that happens and you think, oh, I remember very vividly my own experience as a child, growing up in Jamaica, of being made to memorize poems in school. And I remember when I knew I was going to be a poet or I was going to have this really strong relationship with poetry. I would’ve been about eight or nine, and I wanted as many children, young children, as possible to have access to what I had, which is teachers who loved poetry and taught me poetry and made me memorize all kinds of poems. So I took that as an opportunity to—I read in a lot of schools, I spoke to a lot of children, and then I wanted to work with young women.

I worked with some young women downtown and we came up with a program called the All Flowers Are Roses program. The girls were taught basic self-defense and poetry writing. And it might sound crazy, but for example, if one of the lessons they were taught in the self-defense section was: No means no. No is a complete sentence. And then you have them write poems about that afterwards. You have marvelous results.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: I’m sure

Lorna Goodison: Self-defense and self-expression. And, it really was wonderful. It was a brilliant, wonderful thing, for me, I hope it was great for them.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: (Laughs) I’m sure it was.

Lorna Goodison: But there were things like that, that I felt, I just always wanted an opportunity to be able to just go directly to the children, to young, the very young, and to say to them, poetry can be a lifesaving thing. It certainly saved my life many times. Everything that’s thrown at you, you can find a way to shape it, you know?

Pádraig Ó Tuama: How would you say it’s saved you? You speak so powerfully about that and that it has been a lifesaving thing, but I’d love to hear a bit more about that.

Lorna Goodison: I always had a sense that there was something out there that I had to find and I was going to be troubled until I found it. I was never going to be at peace. I was always searching for it and I searched diligently for it in places where I possibly couldn’t have found it, you know? But having to come back to find it in inside me, and it’s about my faith.

So poets led me there. Even the poets who wrote those wonderful hymns that I would sing at school in the morning. The poems of, say, George Herbert that were made into hymns. “King of Glory, King of Peace, I will love Thee.” I think somebody, was it Freud who said that no matter where you went in explorations of the human psyche, found that a poet had already passed that way? Something like that. I’m misquoting it, but that’s the general idea. But I found more and more that the poets had passed the way in which I know I eventually concluded that that is the way I had to go. Finding my way back to what lasts, what abides.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah, your poetry often does cross into language of hymnody, and that there is old, Christian religion in it, and Rastafarianism, and the Quran and Islam is present there, and Judaism. You draw on the sacred traditions of so many places. What is it about that that interests you so much?

Lorna Goodison: Well, I was very fortunate to have gone to a school in Jamaica where it was an Anglican school for girls. And they were so confident that we would never be looking to any other religion that they actually taught us a course in comparative religion when we got to sixth form. And I don’t think any other school ever did that at that time.

But it made so much sense to me when I was being introduced to all these different religions in the world. And then in my travels, particularly as a writer, I just kept meeting people from every possible religion. And I love those people. These are people I love, and these are people who taught me things. So it just contributed to my sense that, for the world to be as complex and as beautiful and as strange and as varied as it is, I can’t say there wouldn’t be many ways to praise or to worship.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Is poetry a form of travel for you, Lorna?

Lorna Goodison: Yes it is, definitely. My maternal ancestors, some of them came from where you come from, they came from Ireland.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: (Laughs)

Lorna Goodison: And long before I, I’ve been to Ireland once, but I’ve traveled there.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: You have to come again.

Lorna Goodison: I travel there through the poems, of, certainly of W. B. Yeats and Patrick Kavanagh and people like that. I feel I’m in Ireland when I read those poems.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: And what is it that that travel does, for you? I’m curious.

Lorna Goodison: I feel that I have friends all in different places. And that travel does that to me. I really feel that I would’ve enjoyed a good visit with Patrick Kavanagh, for example.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: He’s one of my favorites.

Lorna Goodison: Yes. So I travel there by poetry and, um, does that make sense to you?

Pádraig Ó Tuama: It does. I’ve just always been so interested in how so many of your poems are experiences of the imagination or of memory, and you’re exhibiting that in the craft of a poem, but I’m curious about where travel touches the soul. That’s really what I’m interested in. What does that do for you? Like where does, whether you actually go or whether you’re just imagining that you’re going, what does that do for the soul, for you?

Lorna Goodison: Powerful things. I once had the good fortune to go to Cairo and I just felt absolutely at home the minute I was there. I just felt that it was alright. One of my best examples, I have a friend who said he was terribly afraid of flying. He had real serious fear of flying, but he always wanted to go back to West Africa. So, Jamaican friend of mine, and he said he sort of flew in, you know, just, he was just so terrified all the way. But the minute they got over the continent he was just at peace and happy.

And I’ve had similar experiences in places, you know, where you just get there and you just think, “ah, I feel good here.” So I don’t know. I felt like that in parts of South Africa, for example. I get there and I just feel very happy. I don’t know, inexplicably so, you know, I don’t know. I’m not answering your question very well, but it’s the best I can do right now. (Laughs)

Pádraig Ó Tuama: We’ll take everything you can. Lorna, it’s very good of you to have taken time from your day. Would you read your poem again? We’ll be delighted.

Lorna Goodison: “Reporting back to Queen Isabella.”

“When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: ’The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.’

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.”

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Lorna, thank you so much for giving us the time, and your generosity, and kind words about Poetry Unbound, and all the goodness that you share. Thank you so much.

Lorna Goodison: Thank you. But can I just say that, how blessed we are to know you. I consider you to be a light bringer in this world and blessings on Poetry Unbound and everybody for recognizing that the world such as it is now, can use anybody bringing light. And you, my friend, Mr. Pádraig Ó Tuama, are a light bringer and thank you.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Thanks very much Lorna. How kind, how good to have you here.

We get so many letters from people and anything you send to the Poetry Unbound team, we read, whether that’s an email or on the socials, however it is that it gets to us. Or on Substack we read it all. And, in so many messages that we get, people tell us how much they love the music. And so for that reason, I was really keen to invite Gautam in. And Gautam is the composer of most of the music that we use in Poetry Unbound. And he’s also the Producer of Poetry Unbound. He has a degree in Music Composition from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. And Gautam, hello to you.

Gautam Srikishan: Hello. Thank you. I’m trying to compose myself a little bit from that interview. I really found myself deeply emotional there, so, uh, apologies if it takes me a minute to recover. (Laughs)

Pádraig Ó Tuama: You know, Gautam, the main question that I hear from so many people is the curiosity that they have about what’s in your mind when you’re composing something like this. What do you hope it’ll provide for the listener?

Gautam Srikishan: Yes. you know, it’s maybe a bit trite or obvious to say, but the thing I’m really listening for, or starting from at least, is just a feeling. What does a poem or even sometimes a single line of a poem evoke for me? And then how can the music capture that feeling in some way?

So, sometimes that might come from pure intuition. Maybe I’m just writing the music I hear in my head when I read a particular poem. Maybe it comes from an image. One example that actually comes to mind is when I was working on the first batch of songs for this, Chris Heagle, our wonderful Producer and Technical Director, gave me a prompt to write a piece of music that would reflect the feeling of what it feels like to sort of lie on your back at night and stare up at the night sky, at the stars in the sky. And so that song became “At Dusk,” that prompt became the song “At Dusk.” And so, um, that can happen.

Sometimes, it might come from the idea of a creative constraint. The song “Praise the Rain,” which is more or less like the theme song to Poetry Unbound, that’s the song that plays at the beginning and end of most episodes, came from sort of a creative urge to, to write a piece of music in an odd time signature—or odd to my training in Western music, at least. And in this case, that time signature is seven eight, so seven counts over a measure. But to do that in a way that would feel really grounded, really rhythmic, just easy to nod your head and lilt along to.

So, that’s kind of all just a complicated way of saying, imposing those creative constraints or limits can really be an inspiring way for me to start to engage with the idea of capturing that feeling. And I’m sure that’s something that is true also for poetry, for other art forms.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Yeah. Yeah. I’ve had so many similar conversations with poets who would say the same thing. I got a message on Instagram today from someone who’s turned up who was telling me that they and their daughter sing along with the “Praise the Rain” thing at the beginning and at the end of every episode, (singing) bum bum, ba dum, bum bum, ba dum. So there you are, you are influencing the ears and the humming of people in different parts of the world.

I often think I’ve said this to you before, Gautam, but I often think that the blank space on a page that you’d have on a poem that your music gives listeners to the podcast a kind of an auditory experience of the blank space. Is that something that you’re thinking of too? Some way of supporting the reflection? What goes through your mind with that?

Gautam Srikishan: Yeah. When it comes to, you know, actually putting the music in these episodes, I think it’s really about, yeah, providing sort of like a soft landing place for people. And to do that in a way that neither feels too neutral nor too editorializing, like, “feel this, feel this, feel this!” Music can’t feel something for you. You have to feel it. And so I think it’s about providing something of an open-ended feeling that people can step into with their own reflections, with their own experiences, with their own feelings, and feel supported in that.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Thanks very much, Gautam. I’m delighted that people have had the opportunity to, to meet you and to hear some more about what goes on in your mind about that gorgeous music. And we have the lovely opportunity to meet a bunch of other people who work on the show now as well. So we’ve got a little video of some of the other people who work on Poetry Unbound who are gonna say hello to you all.

Kayla Edwards: My name is Kayla Edwards and I’m the Production Assistant at the On Being Project. One of the things that I most like about working on Poetry Unbound is the challenge in the editing process to use episode structure and pacing to bring the listener into conversation with both Pádraig and the poem.

Chris Heagle: My name is Chris Heagle and one of the things I love about working on Poetry Unbound is how well we collaborate together to make something beautiful.

Lil Vo: Hi, I’m Lillian Vo. I’m an Art Director at On Being. One of my favorite things about working on Poetry Unbound has been collaborating with a variety of artists throughout the seasons, like Myrna Keliher on letterpress prints, or Lucero Torres on photography. It’s been a joy and a super creative challenge to bring poetry to life and make it more accessible through art.

Eddie Gonzalez: Hey, I’m Eddie Gonzalez. I’m the Director of Engagement at the On Being Project, and one of my favorite lines from a poem on Poetry Unbound is from Li-Young Lee’s poem “From Blossoms.”

“There are days we live

as if death were nowhere

in the background; from joy

to joy to joy, from wing to wing,

from blossom to blossom to

impossible blossom, to sweet impossible blossom.”

Amy Chatelaine: My name is Amy Chatelaine and I’m the Digital Chaplain at On Being. And one of the things that I love most about working for Poetry Unbound is being open to the world of our listeners through all of the stories that emerge with the help of a poem, and how these stories make their way back to us in our inbox and on social media, so thank you!

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Thanks for listening, friends. If you want to watch a video of the full event, we’ll put a link in the show notes. And also, to state the obvious, the book is launched now, so if you feel like giving a book to someone in your life who loves poetry or who wants to love poetry more, we’d be delighted if you’d order a copy or two.

Thanks to everybody involved at On Being, at Norton, and to the one and only Lorna Goodison. And most of all, thanks to you, for your listening and letters, for your kindness and communication. I look forward to being in touch with you again in 2023.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.