Chuck Colson, Greg Boyd, and Shane Claiborne

How to Be a Christian Citizen: Three Evangelicals Debate

To be Evangelical is not one thing, even on abortion. This conversation about Christianity and politics with three generations of Evangelical leaders — Shane Claiborne, Greg Boyd, and the late Chuck Colson — feels more relevant in the wake of the 2016 election than it did when we first recorded it. We offer this searching dialogue, which is alive anew, to a changed political landscape.

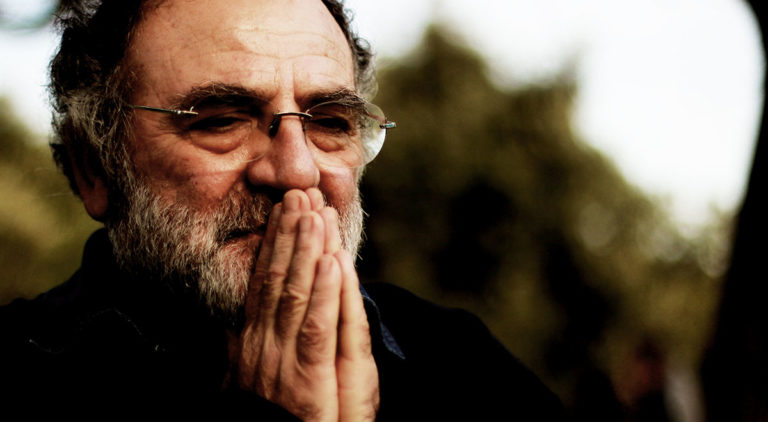

Image by Xevi Casanovas/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

Charles Colson was a Nixon White House counsel and Watergate conspirator who became the founder of Prison Fellowship, a radio commentator, and the author of Born Again, God and Government, and The Faith. He died on April 21, 2012 at the age of 80.

Greg Boyd is founder and senior pastor of Woodland Hills Church in Maplewood, Minnesota, and President of ReKnew Ministries. He’s the author of The Myth of a Christian Nation, Letters from a Skeptic, and Benefit of the Doubt.

Shane Claiborne is the founder of The Simple Way, an intentional community in North Philadelphia. He’s recently written a book, Beating Guns, about the movement he co-leads to transform America’s guns into garden tools. His other books include The Irresistible Revolution.

Transcript

February 2, 2017

Krista Tippett, host: In the wake of the November election, a conversation I had in 2008 with three generations of Evangelical leaders — including the late Chuck Colson — began to circulate around the internet. It was about the proper role of Christians in politics, and it seemed to some as relevant and helpfully illuminating now as it was then, maybe even more so.

White Evangelical Christians helped secure the election of President Trump. Many said that his views on abortion were decisive in that choice, overriding concerns they had on other matters. But to be Evangelical is not one thing, even on abortion. Greg Boyd and Shane Claiborne, are the other two participants in the conversation we offer this hour to a changed political landscape. They continue to be formative leaders in a debate that is as alive as ever within the Evangelical world.

Mr. Chuck Colson: I don’t think you can leave your moral convictions behind when you go in the voting booth.

Mr. Shane Claiborne: For younger folks, we don’t want to repeat the mistakes that the generation before us has made in just this bitter, antagonistic meanness. And if there’s anything that I’ve learned from conservatives and liberals, it’s that you can have all the right political answers and still be mean.

Mr. Greg Boyd: Political issues are, more often than not, very ambiguous and good and honest and decent. And Bible-believing people can have the same values, but they translate into the complexity of politics in different ways, even on things like gay rights and abortion.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Ms. Tippett: Greg Boyd is a mid-career pastor and founder of a Midwestern megachurch. In 2004, he preached a series of sermons rejecting pressure to use his pulpit to endorse conservative candidates and causes. This resulted in 1,000 of his members leaving and eventually landed him on the front page of The New York Times as the face of a new generation of rebel Evangelical pastors.

Shane Claiborne is a now 41 year-old leader in a movement some call the “New Monasticism,” involving many young Evangelicals and former Evangelicals who are building intentional communities together with the poor.

And Charles “Chuck” Colson was a famed and feared special counsel in Richard Nixon’s White House and one of seven senior advisors indicted in the Watergate scandal. But in the midst of that tumult, Chuck Colson revealed that he had been “born again.” His memoir of that title stunned the nation, and after serving a seven-month prison term, he created an original model of prison ministry still very active today, Prison Fellowship. He died in 2012 at the age of 80. But his books and the radio show he founded remain authoritative. Again, this conversation took place in 2008 at a national pastor’s conference in San Diego.

Ms. Tippett: So I’d like to begin with Chuck Colson. And I hope you might help us put some of the questions and challenges of the present into some perspective. I wonder, when you first came to Washington, how would you describe the notion you held and the notion that our culture held about the role of Christians in politics?

Mr. Colson: Well, it’s a debate that’s gone on since the beginning of the church obviously, and it’s gone back and forth. I wrote a book in the mid-80s which was called Kingdoms in Conflict, which was a rebuttal against the excess reliance on politics by Christians, that was then the emerging religious right because I believed there was a fine balance to be drawn between the two spheres.

That book which has now been republished, God & Government, became sort of a handbook for what’s the permissible role for Christians in public policy. I argued that the public square ought not to be naked, that people should be able to express their views freely and openly. As a matter of fact, Christians — I believe — have a cultural mandate to do precisely that, to work for justice. Martin Luther King being a very good example of a Christian who did so explicitly because of the commands of scripture. But at the same time, we have to be very careful not to find ourselves in the hip pocket of a particular political movement. So we have to keep those two balances separate.

Ms. Tippett: Let me ask you, I just reread this week your first book, Born Again, which was your story. And it was an important book at the time. In your early political career, you were not a religious person by any definition the way you are a Christian now. You talk about how, then, even Christians who were involved in politics kept it secret. It was compartmentalized, in a sense. I mean, you describe that you discovered — as you write — to your astonishment what you call “the veritable underground of Christ’s men” all through the government. And within, kind of, 10 years of that happening to you and that being your experience, there was this new Evangelical entry publicly, openly, into electoral politics. I wonder if you could just tell us, as you watched that unfold, why did it happen then?

Mr. Colson: Well, you have to remember, my book, Born Again, which you just referred to kindly, came out in 1976. The title was Born Again. It came out during the New Hampshire primary. Someone ran up to Jimmy Carter, who was then an obscure governor running for president, held the book cover up, and he said, “Oh, yeah, I’m born again.” Christians had been in the fundamentalist hinterlands through most of the 20th century. They’d stayed out of the political limelight. They’d stayed out of politics basically. They didn’t want to contaminate themselves, which was wrong. But that brought them out suddenly.

And it was the abortion issue, among other things, that really suddenly riveted the attention of Christians on the public arena. I saw some of it when I was in the White House as the abortion issue was heating up, but it transformed Evangelical from a pietistic movement into a very activist political movement. But things dramatically changed from ‘76 through the mid-80s. I happen to think now we’re maturing. I think we’ve gotten out of that adolescent stage of being a power block or a special interest vying for power where we’re taking a much more sophisticated look at what it means to be a Christian in public life today.

Ms. Tippett: Now, Greg Boyd, you were also becoming Christian, going to seminary, becoming a pastor, in fact, founding a church and pastoring a church in years in which this Evangelical political power was full-blown, and you found yourself grappling with that as a pastor. You’ve written that you experienced many members of your congregation and your fellow Evangelicals in public life to have no ambiguity about how true Christian faith translates into politics, and you experienced that to be a problem. So talk to us about that.

Mr. Boyd: I first became — sort of came to an awareness about all of this in the ‘80s with the rise of the Moral Majority movement. And there was something about that movement — as an Evangelical, I felt like I was supposed to get on it. I’m against abortion and these other things that they’re for, but the way they were doing it struck me as ugly. So that was the beginning of my questioning. Like, is this my tribe or not? And then in the early ‘90s, I went to a megachurch celebration on the 4th of July. I did a little seminar as part of it. And this is right at the end of the first Gulf War. And they sang a lot of patriotic hymns, which was already making me uncomfortable. They had a major cross and a major flag all together, and then they showed this video with this patriotic music and with this military general describing how God had given us the victory in the first Gulf War.

And at the end of it, the song explodes, it’s triumph, there’s a flag waving as a silhouette in the background. Then you see three crosses and four fighter jets fly down over the crosses and separate and it freeze frames there. It says, “God Bless America,” and the crowd stood up and was just cheering. I started crying. And other people were crying too, but that’s because they were happy. I was crying because I was so grieved by it. And that’s when I really began to seriously think about the distinction between the Kingdom of God, looking like Jesus, serving the world, transforming it by being beautiful on the one hand, and the power over mindset of government on the other. Something has gone profoundly wrong there. And then finally in the — before the 2004 election, I was getting an unprecedented amount of pressure, as I think most pastors of large churches were, to steer the flock in a certain way…

Ms. Tippett: Pressure from within the congregation or from outside?

Mr. Boyd: Mainly from — well, what happens is, the people in your congregation watch Christian television and listen to Christian radio, and there are all these folks saying, “You really need to represent sort of the Christian faith by voting this way against the marriage amendment, da-da-da-da-da-da.” So I was getting a lot of pressure on that, plus a lot of mailings and sometimes phone calls. And I just decided it was a teaching moment, so I did a six-part series called “The Cross and the Sword.”

Ms. Tippett: A six-week sermon, extended sermon?

Mr. Boyd: Yeah. And it was just a time to lay out why, in our congregation — it was really not that new of a philosophy, but I’d never been so clear on it — how political issues are, more often than not, very ambiguous and good and honest and decent and Bible-believing people can have the same values, but they translate into the complexity of politics in different ways, even on things like gay rights and abortion and the Iraq War and all of that. And our job as Kingdom people is to let the politics take care of itself. Vote your conscience.

Ms. Tippett: You had a pretty dramatic response to that sermon within your congregation.

Mr. Boyd: Yeah. It was surprising to me. On the one hand, many people came up crying for joy, because they always felt alienated in their Evangelical church, because of all the flag-waving and the politicizing and all that — the kind of militant sort of Christianity. So they were just overjoyed. But then I also had some people who were absolutely aghast. So we had about 1,000 people eventually…

Ms. Tippett: One thousand out of 5,000 regular Sunday…

Mr. Boyd: About 20 percent.

Ms. Tippett: So here’s something that a member of your congregation said to The New York Times reporter. This was someone who left. They said, “You can’t be Christian and ignore actions that you feel are wrong. A case in point is the abortion issue. If the church were awake when abortion passed in the 1970s, it wouldn’t have happened, but the church was asleep.” And I wonder when I read that just this simple, but strong sentiment, you can’t be Christian and ignore actions that you feel are wrong, if that doesn’t kind of summarize this core unease that has galvanized Evangelicals in politics in the last 30 years, and is also going to perhaps be interpreted differently, but is there as you look towards the next 30 years.

Mr. Boyd: And see, what I would argue there is that we are to transform the world. Absolutely. That’s the call. But the way you do it from a Kingdom perspective is very different from the way you do it from a world perspective. And our trust is to be that we’re to bleed, we’re to sacrifice, we’re to replicate Calvary for women who’ve got unwanted pregnancies, to express the value of the unborn and the value of the woman and then to go full-term with them, not just tell them what not to do, namely, have an abortion, but rather to live life with them.

I think a person who puts a second mortgage up on their house to fund a woman to go full-term and to help raise the child is far more pro-life even if she votes for pro choice than a pro-life person who votes a certain way. Even here, I can — I do have an unequivocal, uncompromising pro-life stance, nonviolence to the core. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to vote for the pro-life candidate, because it may be that I think that the greatest indicator of abortion is poverty and this person I might think is not going to help that issue.

Ms. Tippett: Shane, just following on what Greg just said, in your new book, you write this: “The question is not are we political, but how are we political? Not are we relevant, but are we peculiar?” What do you mean by that?

Mr. Claiborne: It’s not in question whether or not Christians should engage the world that we’re living in. I mean, our allegiance to the God of heaven has to affect the way that we live on earth. But Jesus had plenty of political options to flee society and go into the hills to fight with the zealots and he was very peculiar in how he was political. And I think that’s part of what we are in danger of losing in all of the hunger and drives to be culturally relevant. And one of the examples that we give is the Amish, who are peculiar. I mean, they’re different. They’ve created a different culture in this world. And I think the way that they reacted to this act of terror in their school when their kids were shot, it fascinated the world. So we got a section of our book called “The Amish for Homeland Security.”

[laughter]

Mr. Claiborne: Sort of going — I mean, that looks good. So I think what a beautiful thing it would be if we do have that sense that we’re not to conform to the patterns of this world, but we’re to have a renewing of our mind, a fresh imagination, that that’s part of the call that I see throughout church history. This is nothing new, but over and over, our Christianity gets infected by the world we’re living in and so people go to the margins, they go to the deserts, they go to the abandoned places of the empire that they’re living in, they rethink what it means to be Christian, not just to be a believer, but to actually be a disciple of Jesus that is transformed and converted in the way we live.

[music: “Sunshower” by Simon Steadman & T.T. Magruber]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we’re experiencing an enduring dialogue within Evangelical Christianity on the proper role of religion in politics. I moderated this live conversation in 2008 with three generations of Evangelical leaders who continue to be formative — activist in the New Monasticism movement Shane Claiborne, progressive megachurch pastor Greg Boyd, and the now deceased Evangelical elder statesman Chuck Colson.

[music: “Sunshower” by Simon Steadman & T.T. Magruber]

Ms. Tippett: So, Chuck Colson, I’m curious how you’re hearing all this and what your reaction is.

Mr. Colson: Well, I’m listening to Shane and agreeing with everything he just said, particularly, because he recognizes, unlike the Mennonites, that most mainstream Christians believe they have to be engaged in the moral issues of the day.

Actually, the abortion issue is the oldest issue that the church has dealt with. It started in the first century when the Didache, which was a discipleship manual distributed to all Christians, decried the practice of Rome and Greece in infanticide and abortion. The first letter written by a Christian Bishop in the second century, Athenagoras, was written to Marcus Aurelius to condemn the Roman practice of abortion. It is not a new issue, it has been battled through the centuries and the church has always been in the vanguard of that.

You know, what drove me into the prisons was the massive sense of injustice, the way we were treating a lot of people in prison. And I ended up addressing state legislatures across the country. Had I followed Greg’s advice, I would have just tended to the Kingdom and felt good about my relationship with Jesus, but I couldn’t. I took the issue of justice into the courts from a Christian perspective and argued it expressly as a Christian.

The very words that came out of Greg’s mouth — I don’t mean to take harsh issue with you — about just tend to the Kingdom and let politics take care of itself is exactly what the slave owners said during the Civil War. Their whole argument was they were very good Christians and they were living as pious Christians, and the fact that they owned slaves had nothing to do with their Christianity. It had everything to do with their Christianity. Christians have fought slavery from the beginning.

If you look at great transcendent moral issues, Bonhoeffer — a hero of yours and a hero of mine — Bonhoeffer stood against, in the confessing church, against Hitler. Thank God he did. Wilberforce stood up in the floor of the Parliament in England and stood against the slave trade. You can’t ignore moral evil. We’re called to it as Christians. If it doesn’t strike our conscience, there’s something wrong with us. And we see things are wrong.

Ms. Tippett: So there’s going to be a tension here.

[laughter]

Ms. Tippett: But I think if I can say this, is it necessarily an either/or? Are these different callings?

Mr. Boyd: Could I just say one thing? I don’t think it’s an either/or and here’s, I think, the main — I just read Chuck’s book last week and I agreed to about 90 percent of it.

Ms. Tippett: You read The Faith?

Mr. Boyd: No, God & Government. I was surprised, actually, how much I agreed with it. But see, it’s not an issue of whether or not we should engage moral evil. The question is, is it our primary job — and you even deny this — it’s not the main job of the church to be running the government or to think that we’re supposed to affect the government. That’s not the main job. The main job is to live off the Kingdom, living it. Christians in America differ very, very little from the broader American culture. It’s almost indistinguishable. Here we are, a broken church — profoundly broken church, trying to fix the world. I say we should first take the log out of our own eye before we start taking the speck out of others’ eye. Now that doesn’t mean we suspend all solidarity with prisoners. I mean, I love what you’re doing with prisoners or with the oppressed. Enter into solidarity with them. You say, “Ouch,” but that’s different than saying we can resolve the complex issues of abortion or whether or not the U.S. should go to war in Iraq or all the difficult ones.

Ms. Tippett: Do you, within your community, within your church, try to resolve — whatever that means — resolve the issue of abortion? Are you modeling or living with

that in a different way?

Mr. Boyd: That — our job is to sacrifice for the unborn? Yes. Who you should vote for, because of where they vote on that issue? No.

Ms. Tippett: You have said that we narrow our idea of public engagement to political engagement.

Mr. Boyd: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: But what I also hear you possibly doing is — and maybe the Evangelical movement as a whole has been guilty of this — narrowing the idea of political engagement to electoral engagement, because, again, when I asked a minute ago is it an either/or, when Chuck Colson talks about dealing with state legislatures to make things happen, I mean, you’re dealing with elected officials, but that’s not about who you vote for per se.

Mr. Boyd: Right.

Ms. Tippett: It is about engagement in politics at a different level.

Mr. Boyd: I agree. There’s precedent for that in Paul. When he’s being arrested, he says, “Hey, by the way, I’m a citizen. And therefore, I have a right not to be beaten.” He’s not against talking to political powers, but that’s very different than thinking that we can resolve all the political issues, like we have any kind of special wisdom about that. I don’t think following Jesus gives us any special wisdom about how to fix government.

Mr. Colson: I don’t think you can leave your moral convictions behind when you go in the voting booth.

Mr. Boyd: Of course not.

Mr. Colson: If you believe as I do and as the Catholics teach in Evangelium Vitae issued by John Paul II that the defense of life is part of the Gospel, then for me to go into a voting booth and vote against what is the central truth in my life, that is my commitment to Christ, is impossible. I can’t be schizophrenic. So I think the duty is to say we’re not part of a political movement. We aren’t going to be beholden to a political party, but we are going to vote our convictions, and we’re going to work for our convictions, and we’re going to work for justice in the public square. And when I go into a voting booth, I look at the abortion issue transcendent, because, to me, it’s part of the Gospel. But I also look at defense of marriage, I look at help for the poor, I look at people who do not promote justice. We have 2.3 million people in prison today because we have had discriminatory sentencing laws, all kinds of injustices. I won’t vote for people who support that, because I was in prison. I won’t vote for people who will take human life. I don’t see how you can separate it.

Ms. Tippett: Shane?

Mr. Claiborne: I just wanted to say that I think one of the biggest questions is the idea of political embodiment. How do we live out our politics? What I love about Jesus is he wasn’t just offering a political platform or a nuanced political agenda, but he’s born a baby refugee in the middle of a genocide, lives struggle. So I think part of what we need is we need new political heroes and sheroes. Like for me, Mother Teresa is one of those. I worked with her in Calcutta. I learned from her and she’s just done so much to the cause of decreasing abortions and honoring life from the cradle to the grave. But it wasn’t because she went around wearing a “Abortion is Murder” shirt. Like she said, “If you don’t want your baby, you can give it to me.” And that has integrity to it. You can’t argue with that.

Even Bill Clinton, not known for his pro-lifeness, invites her to speak at his Prayer Breakfast. It just radiates that hope. And to me, that’s what we’ve lost because I do want to decrease abortion. I’m pro-life, which is why I don’t want abortions and I don’t want militarism in war. That also means that I have an obligation to figure out what to do when a 14-year-old girl on my block gets pregnant, which happened. And how do we embody a different future together with her? I think that idea that we allow the integrity of our lives and of our communities to radiate hope is part of where we’re missing, because you can have all the right answers and great rhetoric, but I think that what we’re really hungry for is a Christianity that has substance that people can wrap their hands around, that embodies the Gospel, that’s good news to the poor.

[music: “Lookout For Hope” by Jerry Douglas]

Ms. Tippett: You can listen again, share, or watch this conversation with Shane Claiborne, Greg Boyd, and Chuck Colson through our website, onbeing.org. The video of my live public interview with them offers greater insight into how they interacted with each other. Again, that’s onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Lookout For Hope” by Jerry Douglas]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, in the wake of the election of Donald Trump as president, with the support of many white Evangelicals, we’re exploring Christianity in American politics — and the enduring dialogue and diversity within Evangelicalism about this. The conversation this hour took place in 2008, and began to circulate around the Internet after the November election. We’re putting it on the air again, as it seems newly relevant and helpfully illuminating.

My three conversation partners of three generations are diverse, formative figures. Shane Claiborne has achieved a following among many young Evangelicals for his social activism and his writing. Greg Boyd pastors a socially progressive megachurch. And Charles “Chuck” Colson, who died in 2012, founded Prison Fellowship and became a conservative Christian leader and thinker after serving prison time for crimes committed while a senior figure in the Nixon White House. His writing and the media project he founded continue to form many.

Ms. Tippett: I think I want to throw out a question about whether, even the conversation we’re having today, even these remarks you’re making, which are partly about, again, about having a larger view, a more holistic view, of what it means to be engaged, socially or politically, as a Christian — whether some of that is coming out of what has been learned by Evangelicals in these last 30 years of a certain kind of political engagement. I mean, that you are building on, lessons learned, both in terms of what went wrong and also a new body of experience, a new more global sensibility. I don’t know. How do you react to that?

Mr. Colson: I wouldn’t make any judgments about what is right or wrong based on 30 years of experience when you’re looking at a 2,000-year history of the church, and we’ve had excesses that, as I said at the outset, go both ways. But we strike that fine balance, which no one has done better than Augustine in the “City of God” — that’s a positive classic of Western civilization. And he would be the last one to say we don’t engage in politics. He would say we build the Kingdom, and that is our first task. But in the course of building the Kingdom, we care deeply about the moral condition of the society in which we live.

And Christians have always done this. There isn’t a human rights campaign in history that Christians haven’t been in the vanguard of. Women’s rights were pushed by the church in Rome in the third century, which is one reason that the church exploded because they brought women in and gave them office in the church and Roman citizens followed. So you go back through the centuries, Christians have always engaged the political process when human rights and human dignity and the sanctity of life have been involved.

Ms. Tippett: Well, why don’t you say something, Greg, and then I’ll…

Mr. Boyd: The thing that’s interesting about the early church is that, you’re right, they did that and it exploded. But the reason it exploded, because they were for life and women’s rights and all of that. They’re very egalitarian. But they didn’t have anyone — in fact, they prohibited, for the most part, people serving in government. Our job is to be a contrast society against all that’s out there. Let’s manifest the beauty of God’s reign. And that is attractive and it pulls people in. Then you can find throughout history good examples of people in government doing good things and some of them were Christian, for sure.

But, of course, there’s also a very dark side to governments and Christianity being involved. I mean, it was shortly after Augustine, after the church acquired political power, where he authorized the state to start persecuting heretics. That’s the first time violence started being done in Jesus’ name. And the rest of the history is rather ugly and has brought defamation to the name of Christ. So I would just say we’ve got to be very paranoid. I think we’re starting to learn that.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] That’s a big word.

Mr. Boyd: I think Christians are a little more paranoid of government than they used to be, which is good.

Ms. Tippett: Well, right, and that is kind of where I wanted to go. Because, Chuck Colson, I have seen you write with concern as someone who lived through a period of seeing a president, an administration, corrupted by power or corrupted in the context of power. I’ve also seen you in writing be critical and concerned about hubris that has also emerged, that has also been represented by Christians who are in politics. You’ve seen, in some sense, that dynamic. And Shane Claiborne, you’ve also written about your concern about what happens to Christians, how Christianity itself can be distorted by that relationship with power, with government. So you say it’s a paranoia. It’s a new…

Mr. Boyd: A prophetic distance. How’s that?

Ms. Tippett: It’s a caution that’s come out of this period.

Mr. Boyd: Yes.

Mr. Colson: Well, Christians aren’t perfect. We’re just forgiven. Lots of people have made mistakes. Augustine, one of the great heroes of my life, was wrong when he authorized the state to prosecute heresy. That was a mistake. We’ve made many mistakes, and we correctly repent of those mistakes. But because we make mistakes doesn’t mean you don’t keep trying to get it right. And there is a right way to find it. There is a right way to work for it prudently. And I believe we are growing up as an Evangelical movement because we saw the excesses of the past.

I saw firsthand how the political attraction can destroy very good people. I have seen in the last 30 years a greater phenomenon than the religious right and that is the political illusion, which Jacques Ellul wrote about in the ‘60s, in which he said eventually, with technology, we’ll be able to have instant communications between power and the masses. People will be deluded into thinking politics is going to solve all their problems. That’s a serious problem. And Greg is a good antidote to that, because he’s reminding us as Christians, don’t fall into that trap. You can’t sell it all to politics, which is inherently corrupting.

Ms. Tippett: I’ve had an interesting echo in my mind as I’ve been preparing for this conversation with the three of you. And I interviewed Steve Waldman, who’s the founder of Beliefnet. He’s gone back and looked at the Founding Fathers and the notion of religious freedom and how he thinks we, in our time, have come to look at that through the lens of the culture war. And it has distorted, in fact, our view of the Founders and of the notion of religious liberty.

What I’m getting to is one of the things that shocked him was to find that Evangelical Christians were the great champions of separation of church and state. Siding with Jefferson, on whom they didn’t agree about other things, because he would guarantee their liberty. And James Madison, in particular, was absolutely an advocate of separation of church and state, not because it would make for good government, but because it would make for better religion. He said that whenever government got involved with religion, religion was warped. And then I’m reading Shane Claiborne’s new book. Here we are, 2008, and you are the new generation. And you’re saying something…

Mr. Claiborne: [laughs] One of the people at the front of the hotel, they were like, “You’re one of the speakers at the pastors convention?” And then afterwards, they were like, “We like your dreadlocks, reverend.”

[laughter]

Mr. Claiborne: “They don’t make preachers like they used to.”

Ms. Tippett: OK, so you’re cool. We’ve established this. And you are, it seems to me, rediscovering that same insight that James Madison articulated or that those early Evangelical Christians in the early colonies articulated.

Mr. Claiborne: Well, and I think — I’ve got a great friend and teacher named Tony Campolo out in Philadelphia, and one of the things that he always says is, “Mixing church and state is like combining horse manure and ice cream. It may not do much damage to the manure, but it’s sure gonna mess up the ice cream.”

[laughter]

Mr. Claiborne: And I think what we’ve seen is Christianity, at its worst, is when we fuse these together. And it’s quintessential in the culture that we’re living in where the U.S. currency says, “In God We Trust,” but our economy reeks of the seven deadly sins, of lust and gluttony and greed. And the U.S. flag is on many of the altars and kind of colonizing this. Even here at the National Pastors Convention, I mean, there’s an exhibit for the U.S. military. These are the things that I think create confusion in people.

And so when I was in Iraq, I was in Baghdad with the Christian peace team during the bombing in March of 2003, and I went very much because what became so unmistakably clear to me was what’s at stake right now in the world is not just the reputation of America, but the reputation of Christ and what it means to be Christian in this world. And I want people to know the love and grace and enemy love of Jesus.

Ms. Tippett: Enemy love?

Mr. Claiborne: Yeah, and we’re not in a lot of ways getting closer to that.

Ms. Tippett: Chuck Colson, you wanted to say something?

Mr. Colson: Just let me add one thing to that. C.S. Lewis wrote a wonderful essay about Christian patriotism. He said, “It is not wrong to love your country, because God has put you in an area where you’re supposed to love the world, but all you can love are your neighbors.” Aquinas said the same thing about military service. He said, “Someone who serves to defend the innocent is acting out of Christian love. You can love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, mind, and soul and also love your country as a way of loving your neighbor.”

Mr. Boyd: This is a real fundamental difference between us. And what concerns me most, Chuck, is that most of the young Christians that I know who sign up for military service are so nationalized it doesn’t even occur to them that there might be any conflict between picking up a gun and killing someone, and Jesus saying, “Love your enemy, do good to your enemy, without any qualification serve your enemy.” I at least want people to ask the question, but it shows you how blended the Christianity of America has been to nationalism. And my passion is that we’ve gotta show the radicalness of the Kingdom first and then worry about all this other stuff. But if this doesn’t get done, there’s nothing worth getting done.

Mr. Colson: The New Testament’s pretty clear that you render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and render to God what is God’s. The New Testament is also very clear that you are to respect the authorities because they are appointed by God to wield the sword in order for us to live peaceable lives. So government has a role biblically, well established by 2,000 years of reflection, that the job of government is to preserve order and to do justice and to restrain evil.

Mr. Boyd: Sure.

Mr. Colson: As a military man, I served my country proudly and would again. A military man takes an oath to support the Constitution, because it’s God’s ordained instrument to preserve order. And without order, you’ve got chaos.

Mr. Boyd: But, Chuck…

Ms. Tippett: I think Shane wanted — Shane Claiborne is raising his hand, for the radio audience.

[laughter]

Mr. Claiborne: I think this idea that we’re to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s is an interesting one, and I think a lot of times we miss the point of what Jesus was doing there, which I think He’s spinning everything on its head and calling into question, “What is Caesar’s?” Like Caesar can have his coins, right? Like Caesar can print a piece of metal with his picture on it. Give it back to him. But I’ve made humanity and that has my image on it. Caesar has not right to that. And I see in Jesus what John Howard Yoder calls “revolutionary subordination.” This idea that we’re to submit ourselves to the authorities, but we expose their evil and their darkness by allowing them to throw us in jail. Or Dr. King says so well, “You can throw us in jail, and we’ll still love you. You can threaten to burn down our houses, and we’ll still love you. You can put your dogs on us and shoot us with your water hoses, and we will still love you. But we will wear you down by our love.”

[music: “Tete a Tete” by Ismaël De Saint Léger]

Ms. Tippett: Shane Claiborne, in conversation before a live audience with two other Evangelical leaders of different generations, megachurch pastor Greg Boyd, and the late Chuck Colson. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. As this discussion at the National Pastors Convention drew to a close, an audience member asked the panelists where the dialogue about same-sex relationship factors into the future of the Evangelical movement. This conversation happened in 2008, but has gained new traction as an insight into enduring intra-Christian dynamics and discernment.

[music: “Tete a Tete” by Ismaël De Saint Léger]

Ms. Tippett: Chuck Colson, would you like to go first?

Mr. Colson: Well, Romans I makes it very clear that creation, that which is made clear to them, is made known to them, the existence of God in creation. And Paul immediately goes on to say those who turn away from it have exchanged the truth for a lie and they end up — and then he talks about homosexual behavior. The reason he does, I believe, is that’s the clearest example of the fact that there is a natural moral order corresponding to the natural physical order.

And so something which is so plain on its face is not normative. That doesn’t mean we don’t love homosexuals. We do and should. And we should not be judgmental about them and we should not be prudish about it, but we have to recognize that it is not the way men and women are made. That’s pretty much what Paul is saying in Romans I. Not that he’s judging them as inferior, but simply that they violate the moral order, which is intended to conform to the physical order.

Ms. Tippett: I think the question is about how the church and how Evangelical Christianity grapples with the fact that even the statement that you just made, which is so plain to you, is not the way everyone sees it. And so — and this issue has been so bitterly divisive.

Mr. Boyd: If I could weigh in, it seems to me that there’s two fundamental issues that we Evangelicals do have to wrestle with. The one is simply the terrible, abysmal track record the church has towards gays. That the reputation out there is that Evangelicals are homophobic, and I don’t think that’s liberal media that’s spinning that. I think we’ve earned the right to have gotten that.

We have a sin gradation list — and I do see it as sin. I think Chuck is absolutely right. Romans I, it’s not God’s ideal. It misses the mark. Hamartia, that’s the word for sinning. It misses God’s ideal. But what’s happened is we have a list and our sins like gossip and greed and gluttony and not caring about the poor, and all the stuff that’s mentioned all the time in the Bible, we minimize.

You can be a church member and have that stuff, but the homosexuality issue is all of a sudden the deal-breaker. And who christened that the deal-breaker sin? I don’t get that. I used to wonder why did Jesus attract prostitutes and other sinners that were judged by religion, and the church doesn’t? They tend to stay away from us as much as the Pharisees. And one of those reasons might be that Jesus never made a public policy trying to pass laws against them. And here’s where politics can get in the way of our Gospel message. They don’t want to hang out with us, because we made a platform out of going after them instead of our own sins, instead of the divorce that’s destroying the family. And so I think we got to wrestle with that one.

Mr. Claiborne: When I got to Philadelphia, I met a kid in college who told me he was attracted to men, and he felt like God had made a mistake when God made him. That’s what he felt from the church, that’s what he felt from society. He felt that from hearing things like this is not natural. So he felt like God made a mistake, and he wanted to kill himself. And that breaks my heart. And I feel like, if that kid can’t find a home in the church, who have we become?

Ms. Tippett: So here, illustrated on this stage is the fact that to be Evangelical is not one thing.

Mr. Boyd: No, apparently not.

Ms. Tippett: That you can love the Bible in common and take it seriously and have different interpretations. Some people might listen to you talking about the Kingdom, Greg, and think that that’s not real-world talk, but it is absolutely is real-world talk for you.

Mr. Boyd: Absolutely.

Ms. Tippett: I think this is a great illustration of this moment of discernment that Evangelical Christianity is in. A question I have is — and this is maybe another way that we are all influenced by the culture we live in — the ways we know to grapple with hard questions on which we disagree are to fight and debate and be angry with each other. Are there resources deep within Evangelical Christianity that you have in common, that everyone in this room has in common, to possibly move towards — not necessarily move towards the same answers, but move towards walking together as Evangelicals with these questions? How do you think about that?

Mr. Colson: Well, let me give you a personal anecdote that may help you. When I first came to Christ, before I went to prison, a small group of men, five of them, kind of embraced me, and I was discipled by them. One of them is, today, former governor of Minnesota, Al Quie. One of them was a man by the name of Harold Hughes who was as liberal a Democrat, anti-Vietnam War, opponent of Richard Nixon, as you’d ever find. He heard me give my testimony one night. He said, “I just listened to you. You love Christ. I love Christ. We’re brothers. I’ll stand with you anywhere.” Embraced me. Great big, 280-pound, ex-truck driver, ex-alcoholic, and all through Watergate and all through the years that followed, he helped me get started in the prisons. We were best friends. We never probably voted for the same candidate, but you can love each other. It doesn’t mean you even have to like each other, but we’re commanded to love each other. And sure, we’re going to find political expression in different ways. I think there are some issues that are transcendent for all of us. I think justice itself is a transcendent issue, but, yeah, we could…

Ms. Tippett: And yet, it’s sometimes hard even to talk about what justice looks like or where to begin in seeking justice.

Mr. Colson: Oh, I think the civilized world has had enough experience at what is just to be able to make it. I don’t think we can much improve on the Greek’s definition or maybe the Bible’s definition is even better, which is shalom. That is the condition in which there’s human flourishing. I think we can agree on that. I think all Evangelicals would agree on that. But we don’t march lockstep into the ballot box, but certain issues demand that we get involved.

Now there is a respectable Mennonite tradition — Yoder, and others are part of it — which say we just will stand back, create an alternative community, let the world see a better way. That’s an honest difference of opinion that’s gone on for hundreds and hundreds of years. I happen to belong to more of a Niebuhr school that we are to make an impact for Christ in how we live our lives and in challenging the political systems, but you can still be an Evangelical and come from either one of these traditions.

Mr. Claiborne: You know, Krista, I think that’s one of the things that’s exciting about this conversation, especially for younger folks, that we don’t want to repeat the mistakes that the generation before us has made in just this bitter, antagonistic meanness. And if there’s anything that I’ve learned from conservatives and liberals is that you can have all the right political answers and still be mean. And nobody wants to listen to you if you’re mean. [laughs] And I think that one of the things that we can do is learn to disagree well. And I think there is a new conversation happening with Evangelicalism in post-Religious Right America that is much healthier, and we can actually learn to disagree well and wrestle with hard truth.

Ms. Tippett: Shane, you talk in your book — in your new book about the virtue of confessing sins — and you feel that Evangelicals have some sins to confess in terms of how this line of religion and politics has been lived for a few years. Along those lines, I just want to ask each of you, thinking about one thought, idea, next step along this process. Chuck Colson, I like it when you say that the Evangelical movement is in the process of maturation, that this a moment of growth. What would you like to offer, each of you, as one thing for everyone to take out of the room back to their congregations? Something practical as well as theological?

Mr. Claiborne: Confession, I think, is a sacrament. There’s something mysterious that happens when we begin with our own contradictions and struggles and we share those. And yet, isn’t it wild that it flies in the face of everything that power stands for? I mean, you can never confess that you did anything wrong. It doesn’t matter if you’re Bill Clinton or George Bush, like you don’t confess until you get busted on tape or whatever, for doing something wrong with Monica Lewinsky or doing something wrong in Iraq. It’s so contrary to power to confess. And yet, it’s the center of our faith is that we confess that we’re broken people.

And that’s the good news of Jesus, is that the Gospel is not for healthy people, but for sick folks. This is a part of what we lost within Evangelicalism because we end up thinking that you got to look like you have it all together to be a part of the church, and I lament that. When people see Christians that are willing to get on their knees and beat our chests and say, “God, have mercy on us sinners,” and not the kind of Christians that just point our fingers at other people and say, “Thank you that we’re not like them.” So I think the world’s really hungry for Christians that have that humility, and that feels a lot like Jesus.

Mr. Boyd: Amen. I always feel like I give a biblical commentary to what you just said, but Paul says in 1st Timothy 1 that Jesus came into the world to save sinners, “of whom I am chief.” That’s a saying that we should all be saying, “I am the worst of sinners.” And Jesus, of course, said to us, “Why do you go looking for a dust particle in your neighbor’s eye when you got a two-by-four sticking out of your own eye?” And he’s not just talking to people who are exceptional sinners. They’re probably better than the average. But the Kingdom’s stance of humility is that whatever I think I see in someone else’s eye I should — or in someone else’s life — I should regard mine as being worse than that. And if a fraction of Christians did that, instead of being known as being moralist and posturing and all of this, we’d be known as the most humble, serving, loving, servants in the world. And I believe that that’s what looks like Jesus, and that’s what brings people into the Kingdom, and that’s what’s eventually going to transform the whole world. Be like Jesus.

Mr. Colson: My one message would be agreement with both of those. Confession, certainly, and humility, because the last thing we need to do is be arrogant. We have nothing to be arrogant about. The only thing we have is a gift which God has given us, and we should treasure it and share it winsomely and lovingly with the rest of the world. My one prayer would be that Christians would understand better what they really believe — the core of their beliefs, why they matter, why we believe them and how to present them winsomely in a world that is so polarized and divided and alienated. Let’s be agents and instruments of reconciliation, which is what the Gospel enables us to do.

Mr. Claiborne: I think that when we’re called to be this new humanity, this new kind of people, a part of what we’re — we have an identity that transcends nation or family that as Chuck was saying, a love for our own people is not a bad thing. But our love doesn’t stop at the border. Right, I mean, we’ve got a transnational family that’s incredible, that’s ancient. I really learned that when I was in Baghdad. When I was over in Iraq, I met with this bishop after one of the most powerful worship services I’ve ever seen. I said, “I had no idea that there’s so many Christians in Iraq.” He looked at me, and he was very gentle, but he said, “Yeah, this is where it all started.”

[laughter]

Mr. Claiborne: He said, “That’s the Tigris River and that’s the Euphrates. Have you heard of them?” Then he told me, he said — I kid you not — he said, “You didn’t invent Christianity in America. You only domesticated it. You go back and you tell the church in the United States that we are praying for them to be the body of Christ.” That just continues to echo in my mind, and I think it put me in my place, of where, we’re not the center of the world, but we’re a part of an ancient story and a beautiful narrative.

Ms. Tippett: Thank you so much to Shane Claiborne, Greg Boyd, and Chuck Colson.

[applause]

[music: “Goodnight and Go (Instrumental)” by Imogen Heap]

Ms. Tippett: Shane Claiborne is founder of The Simple Way, an intentional community in Philadelphia. And he’s the author of The Irresistible Revolution, Red Letter Revolution, and more recently, Executing Grace: How the Death Penalty Killed Jesus and Why It’s Killing Us.

Greg Boyd is founder and senior pastor of Woodland Hills Church in Maplewood, Minnesota, and President of ReKnew Ministries. He’s the author of The Myth of a Christian Nation, Letters from a Skeptic, and Benefit of the Doubt.

And Charles “Chuck” Colson was a radio commentator, founder of Prison Fellowship, and the author of Born Again, God & Government, and The Faith. He died on April 21, 2012 at the age of 80.

[music: “Goodnight and Go (Instrumental)” by Imogen Heap]

Staff: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Bethanie Mann, Selena Carlson, and Rigsar Wangchuck.

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoe Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing our final credits in each show is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the front lines of social change worldwide, at Fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation – a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.