Faisal Mohyuddin

Prayer

Faisal Mohyuddin’s poem “Prayer” describes a practice of devotion. It’s a spacious and hospitable poem, filled with references to ritual and the body, and an invitation to share in the warm light of a household lamp.

A question to reflect on after you listen: What rituals do you use to anchor yourself?

Guest

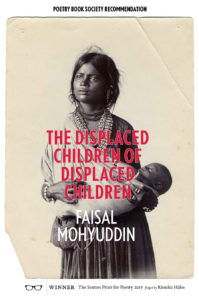

Faisal Mohyuddin is a writer, artist, and educator. He is the author of The Displaced Children of Displaced Children, winner of the 2017 Sexton Prize in Poetry and a 2018 Summer Recommendation of the Poetry Book Society. His other awards include the Prairie Schooner's Edward Stanley Award, a Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize, and an Illinois Arts Council Literary Award. He teaches English at Highland Park High School in Illinois, serves as an educator-adviser to the global not-for-profit Narrative 4, and lives with his family in Chicago.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama. I’m a poet from Ireland. And when I grew up, we learned poetry in Irish and English off by heart, every week, from the age of five. But when I was 11, I found myself picking up a piece of paper and realizing that I wanted to write a poem about things that couldn’t exist, but still do exist. And poetry opened a door for me to speak about everything that I can see and everything that I can feel, to put it all onto a piece of paper.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Prayer” by Faisal Mohyuddin:

“you cleanse the uncovered

regions of your body

then stand at the foot

of prayer mats facing

the qibla unfasten

your cluttered mind

from the tangible hold of secular

trances bow down

before the cascading

glow of God’s mercy submit

to a centripetal course towards the gates

of a more perfect emptiness

here now

you can plunge into the most secluded

chamber of the soul commune

with your share of the universe’s

initial burst of light eternal light

housed within the lamp of mystery

waiting to be

beheld five times a day”

For me, when I read this poem, I’m brought, with great generosity and hospitality and invitation, into an experience of language and positioning the body in prayer that’s utterly unknown to me. And I love the hospitality of the poem, that the poem brings you into that. Faisal Mohyuddin has done something beautiful here in the structure of the poem. This poem has no punctuation in it whatsoever, no periods, no commas, no em dashes. And this poem is arranged in ten elegant little verses. And they’re scattered across the page in a way that makes you think of ten prayer mats in two staggered lines, looking toward the direction of prayer. And there’s something, for me, as somebody who did not grow up in this tradition, that is so beautiful — to be brought into that; that the poem itself locates me in a practice that is unknown to me. And I’m always drawn into the richness of this prayer and the richness of this poem by thinking, there’s people who will look at this poem and immediately feel at home. For me, I immediately feel invited somewhere new; but other people would read this and go, “I recognize this.”

This poem is filled with physicality, especially the first part of it. The uncovered regions of your body stand at the foot of prayer mats, facing Qibla and then bowing down. So this poem is filled with instructions, initially, about what to do with your body. And I, as a young person, hated going to mass, standing up, sitting down, kneeling, the whole lot, blessing yourself. It all seemed ridiculous to me. But now I look back and think that there’s something very powerful about having practices in the body that hold you together.

I flew here the other day, and sitting next to me was a guy, and when our plane was taking off from Dublin, he blessed himself. I noticed that; and then, as we were landing, we happened to be talking. And we were chatting away — he’s an American guy of a Polish family; we were talking about language and talking about Polish poetry. And totally naturally, in the middle of it, he blessed himself again, because we were landing. And he didn’t interrupt himself one bit. He’s younger than I am; I’d say, a man of 30. And I loved that physical prayer. Part of me wanted to say, “Do you believe in God?” But I think that’s unnecessary, because it kind of doesn’t matter. Using his hand to bless himself was a physical reenacting of something that was holding all of us together in that plane, that hurtling piece of tin, flying through the air. [laughs]

This poem turns, because it moves prayer from the idea that the person is the one who’s prayed into being by the direction of the light and that the light is the thing that nurtures the person.

This poem moves from that glorious language about mystery into something as simple as a lamp. And the lamp is something we all might have in a home. A lamp is old. A lamp predates electricity. A lamp might bring to mind a wick, some oil, a flame, and that that is a window into the magnificence of God’s mercy, into the magnificence of prayer, into the magnificence of mystery, but also, this perfect emptiness. And I love the slight anarchist way of describing God as perfect emptiness — that takes courage, I think, to describe the mystery of religion there, because it’s saying, even if you don’t believe it, believe that it might be a perfect emptiness, a blank canvas, perhaps, upon which to project all the experiences that we don’t know what to do with, and that that itself can be enough.

I think this poem offers the people who read it — whether they’re people who are from one tradition or another, whether they’re people who follow a path of religion or don’t — this poem offers us the opportunity to imagine, what might it be like to have a practice that helps us move away from things that distract us and settle down into the simplicity of looking at mystery through the lens of a lamp? What is the warm butter light of a lamp that helps you hold yourself together? Whatever that might be, turn towards that.

“Prayer” by Faisal Mohyuddin:

“you cleanse the uncovered

regions of your body

then stand at the foot

of prayer mats facing

the qibla unfasten

your cluttered mind

from the tangible hold of secular

trances bow down

before the cascading

glow of God’s mercy submit

to a centripetal course towards the gates

of a more perfect emptiness

here now

you can plunge into the most secluded

chamber of the soul commune

with your share of the universe’s

initial burst of light eternal light

housed within the lamp of mystery

waiting to be

beheld five times a day”

Lily Percy: “Prayer” comes from Faisal Mohyuddin’s book The Displaced Children of Displaced Children. Thank you to Eyewear Publishing, who published the book and gave us permission to use Faisal’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unbound is Tony Liu, Chris Heagle, Kristin Lin, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota Land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.