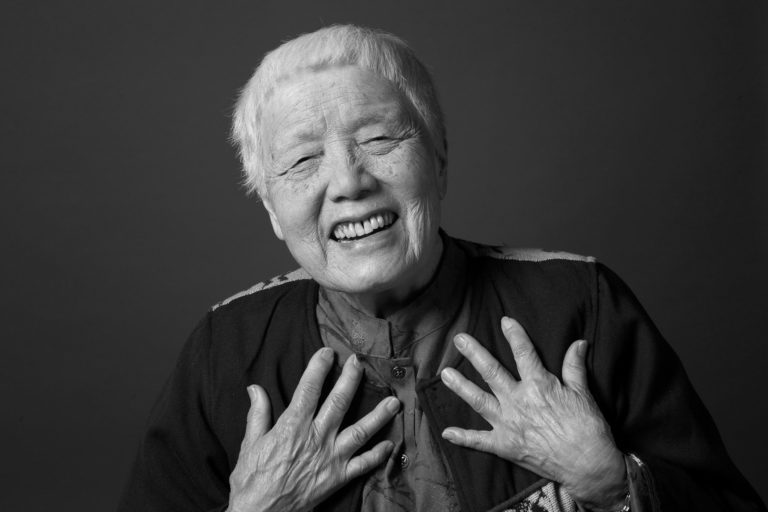

Grace Lee Boggs

A Century in the World

Chinese-American philosopher and civil rights legend Grace Lee Boggs turned 100 this summer. She has been at the heart and soul of a largely hidden story inside Detroit’s evolution from economic collapse to rebirth. We traveled in 2011 to meet her and her community of joyful, passionate people reimagining work, food, and the very meaning of humanity. They have lessons for us all.

Image by Robin Holland, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Grace Lee Boggs was a philosopher and a civil rights leader and a founder of the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center. She authored the book Living for Change: An Autobiography. The documentary about her life and work is called American Revolutionary: The Grace Lee Boggs Story.

Transcript

August 27, 2015

RICHARD FELDMAN: So this is Detroit.

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: You’re entering a kind of parallel urban universe — a Detroit rarely seen in news coverage of the city. This pocket of innovation and vigor flourished within more familiar recent pictures of decline.

And right in the middle of it all has been Grace Lee Boggs — the Chinese-American philosopher, civil rights legend, and social visionary. She’s just celebrated her 100th birthday. So we’re revisiting our 2011 pilgrimage to Detroit to meet her. We discovered her at her home, surrounded by joyful people re-creating their corners of the world. Their innovations are now ironically struggling to continue amidst Detroit’s economic rebirth. Yet to meet Grace Lee Boggs again, together with her community, is to gain perspective on all of our work to re-imagine and navigate the most challenging dynamics of our time.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

GRACE LEE BOGGS: There’s something about people beginning to seek solutions by doing things for themselves; that we have that capacity to create the world anew.

GLORIA LOWE: Possibilities are just what they are, you’re only limited by your own imagination. You know, I’m not a designer, but no doubt, I have thoughts, I have visions. And they’ve been put into play.

WAYNE CURTIS: Is just not a warm and fuzzy garden. We’re not just growing food, we’re rediscovering ourselves and redeveloping our identity.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

[Sound of driving]

MR. FELDMAN: You’re on the east side of Detroit. This was obviously a very wealthy, where the upper management used to live in the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s. Where Grace lived, it was still — you could see pretty strong housing stock. Detroit was the largest homeowner population of any city in the country. It went from less than a million people in 1912 or 1913, to two million in 1950, to now less than 760,000. Detroit’s the size of, so you know, it’s the size of 150 square miles, which means it’s equal in size to Boston, Manhattan, and San Francisco altogether. And one-third of the land is vacant now.

MS. TIPPETT: Richard Feldman is a former autoworker and longtime labor and community activist. Raised in Brooklyn, he came to Michigan to study in 1967, got involved in the student movement, and stayed. He came to know Grace Boggs and her husband James Boggs back then. Jimmy Boggs, as everyone knew him, died in 1993. He was an African-American autoworker, organizer, and civil rights thinker. Richard Feldman first experienced Grace and Jimmy Boggs as the heart and soul of the civil rights movement in Detroit.

[Sound of driving]

MR. FELDMAN: Why Detroit is where it’s at is because this all started in 1980. We’ve had 30 years of living with what people think is a global economic crisis. And folks — enough folks have known that sort of protest politics or expecting the government or the corporations to come back — it’s an absurd thought. We were talking yesterday — this is yesterday, because there’s a bunch of us that meet weekly with Grace.

One guy is Ron Scott, who was the founder of the Black Panther Party, who is creator of these Peace Zones for Life, who was talking about the future and the past, saying that within the seeds of his past was the future. And then to say how Jean and I have been working with Jimmy and Grace since we were like 20. She was saying there’s still a disconnect and we don’t know how to create the connection between understanding history and the process that young people are so good at now creating ways for people to tell their story and become personally empowered. Just an amazing moment because folks know there’s enough people around that people don’t know where else to go except to be and to ask each other these questions.

MS. TIPPETT: Grace Boggs’ longtime home in Detroit is also the headquarters of the Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership. It was founded in the 1990s by friends of Grace and Jimmy Boggs. She was born Grace Lee, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. She came into the world above her father’s restaurant in Providence, Rhode Island.

[sound of arriving at Grace Lee Boggs’ home]

MS. TIPPETT: You walk into her living room, and you’re enveloped by energy and by history — books, posters, artwork, that represent the endless projects this place has sparked or touched. The people who crowd around to listen to our interview are friends and co-workers. They are all people who radiate passion. And they all manifestly adore Grace Boggs and look up to her as a philosopher and an elder.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, maybe a place to start is with these words “revolution” and “evolution,” that you started using those terms, writing about them in the ’60s. I mean, maybe we could start by, you know, how your sense of what those words meant in the ’60s, what they mean now.

MS. BOGGS: In the ’60s, as you know, all here broke loose, mostly in the big cities, but Detroit was one of the biggest. And that outbreak, that explosion, the media called it a riot because it was obviously a breakdown of law and order. Radicals and the black community called it a revolution. And it made me think what is the difference between a revolution and a rebellion? I never thought about it.

And I realized that rebellion was mainly an explosion of anger, and revolution was a tremendous leap forward, tremendous evolution in consciousness and responsibility and a new way of thinking. And that’s how the events of the city have shaped my thinking. And I think, until one has had an opportunity to understand how language constantly has to change in response to changing events and how we are living in a time of enormous changes, and we have the opportunity to change our thinking, to change our philosophy, by responding to and really trying to understand what’s happening, what time it is on the clock of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: So, you know, one thing I’m so struck by in your biography is you got a PhD in philosophy in 1940. Is that right? A PhD in philosophy as a woman, as an immigrant woman, what’s so striking about you — and I feel one of the reason also people are turning to you now — is how you’ve merged this power of ideas, the necessity of thinking and ideas as well as actions and strategies for change.

MS. BOGGS: Well, you know, I was born in 1915 and I was in college as an undergraduate in the 1930s. And many of my friends became very radical. They flirted with the Communist Party, and I decided to drop all my classes and take up philosophy. I don’t know why. If you would ask me what philosophy is or was, I would not have been able to tell you. But somehow I knew that we were at one of those breaking points where we had to begin rethinking things.

And that gave me the opportunity to become a graduate student in philosophy and to begin reading Hegel who had danced around the tree of liberty in 1781 as a young man. And then, in 1831, had experienced the contradictions of the French Revolution and was talking about the need to expand our subjectivity and to see how the positive has to be achieved through the labor-patient suffering of the negative, and that began to give me a whole new way of thinking about change and how it develops, how it takes place.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, here’s another way you’ve paraphrased Hegel and put him into your own words in a public discussion, that “Progress does not take place like a shot out of a pistol; it takes the labor and suffering of the negative. How to use the negative as a way to advance the positive is our challenge.” I think it’s mysterious that we advance through what is negative. Do you know what I mean? I mean, this is a big, big quandary for human beings.

MS. BOGGS: I think one of the things that I discovered after I came to Detroit and married Jimmy, who had been raised in Marion Junction, is that you have to make a way out of no way. And as I began looking out the window here in Detroit, when I came here in ’53, there were two million Detroiters, the place was just booming. My husband’s plant, Chrysler, employed 17,000 workers. And after that, because of the technology introduced during the World War, the plant was automated and began employing 2,000 workers and instead of booming, the neighborhood began being pockmarked with vacant lots.

And what happened was that the African-American elders who had been raised in the South looked at those lots and they saw not light, but promise. They saw an opportunity to grow food for themselves as a community, and they also saw an opportunity to help young people think of change and development in a more — in a slower way rather than in terms of a quick fix. So out of the negative came this enormous positive of the urban agricultural movement and that’s what you see in Detroit every day. You can see the possibility of giving up, of moving forward, making a little leap.

MS. TIPPETT: And that is so striking about your perspective. I think, for many people, Detroit is a symbol of the failure of the old, right? Of blight and of despair, and you know Detroit as a symbol of whatever the new society is that’s building.

MS. BOGGS: Well, I think we have a very — most Americans have a very short-range idea of history. They don’t realize that mass production only began about 100 years ago, at the beginning of the 20th century. They don’t realize that capitalism has only existed for a few hundred years. They don’t realize that there’s been a huge evolution of culture and paradigm shifts in everything, in governance, in education, in work down through the ages. And it’s that lack of a long-range view that can make you think that when change happens, when you see ruins and disintegration, you see collapses, it’s the end of life.

One of the things that I learned from my father is that a crisis is both a danger and an opportunity. That’s in the Chinese characters. And how you take advantage of the opportunity of the crisis rather than become despairing because of the danger and fearful is something we’re facing all the time, particularly at this time. And it’s a philosophical approach I think that is very much needed and also alive here in the city of Detroit.

[music: “Norman Rockwell” by Cloud Cult]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: a conversation in the living room of the Chinese-American philosopher and civil rights legend, Grace Lee Boggs. She turned 100 this summer.

[music: “Norman Rockwell” by Cloud Cult]

MS. TIPPETT: So one of the things you’ve been talking about a lot recently is reimagining the nature of work.

MS. BOGGS: Yes, reimagining.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MS. BOGGS: I mean, the opportunity that we now have to reimagine everything, to reimagine work, to think of it as productive not only of things, but of well-being, to think of governance in a different way, to think of education in a different way. What an opportunity, what a time to be alive. We’re not only being, but we’re non-being and becoming.

MS. TIPPETT: And one of the interesting things you’ve said, I think, one of the many, is that whereas the rebellions of the 1960s focused a lot about — around the empowerment of individual identities for women, for African-Americans, that what we’re undergoing now is more about developing a new kind of human identity.

MS. BOGGS: The ’60s was — raised a lot of very human questions, but people thought more in terms of rights than in terms of advancing our humanity. But out of the ’60s has come that opportunity to think differently. If you look at the T-shirt over there that Barbara has, it has “Revolution, Evolution.”

MS. TIPPETT: The “R” is bracketed, so it’s [R]evolution.

MS. BOGGS: And how that — I mean, having to think in those terms of “revolution as evolution” rather than as getting more power, more control, is a very more enlightened way to think.

MS. TIPPETT: But there’s, again, this comes back to there’s so much pain and loss that accompanies that decline of what was, even if it wasn’t good for us in many ways.

MS. BOGGS: Well, is it a terrible loss not to be able to buy a big car, or is it an opportunity to regain our legs? In the sense of the — I drove until a few years ago and I do not want to say that I’m against driving [laughs]…

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] OK.

MS. BOGGS: …but I think you look at the “Motor City” and how the auto industry has depopulated the city, has made us dependent upon cars, has done so much to remove people from the streets and to the decline of neighborhoods so that people very often will drive into their garage adjoining their kitchen without even waving to the neighbors, and how we have to restore the neighbor to the hood. That a lot of the decline of neighborhoods and of community is due to the auto industry.

MS. TIPPETT: But — and that very disintegration of the neighborhood and of community makes it hard for us to know how to care for each other in the pain and loss that comes with people losing their jobs, losing their houses. Do you also see people in Detroit learning new ways to be there for each other in this transition, right, in the transition between the old and the new?

MS. BOGGS: Sitting over there is Gloria Lowe, who wrote an article called “Turning to One Another Instead of Against One Another” as the opportunity has been opened up by the economic crisis. To have lost our ties with one another, to have become strangers and even enemies of one another and competitors, we’ve lost a lot of our spirit.

MS. TIPPETT: Our spirit, yeah.

MS. BOGGS: We have so much to rediscover. There are so many creative energies that are part of human history that have been lost because we’ve been pursuing the almighty dollar. We haven’t recognized at what expense we’ve done that, the expense not only of the earth, not only of people of color, but of our own selves. We no longer recognize that we have the capacity within us to create the world anew. We think we are only the victims.

MS. TIPPETT: So if I ask you where your philosophy of that, of what the new world looks like, where does that come from? How do you envision that?

MS. BOGGS: Well, it comes from a lot of things. It comes from having been born a long time ago [laughs]. It comes from having been born female. It comes from having decided to study philosophy. It comes from really, I think, understanding how the French Revolution created a kind of democracy, but also robbed us of a great deal. It alienated us from our labor, it made us dependent upon technology, it made us think that economics is more important than our relationships with one another. We have now the opportunity to rediscover who we are.

[Sounds of car door slamming and walking]

MS. TIPPETT: Gloria Lowe, who Grace Boggs mentioned, is the founder of We Want Green, Too! She was a final line inspector at Ford Motor Company before a door came crashing down on her one day. Now she trains veterans in the crafts of construction — vets who’ve struggled with injuries, substance abuse, and incarceration. They work on recently purchased as well as abandoned homes. So we visited the two-story, turn-of-century house where she now lives, rehabbing it room by room. She got into this through some of the extended networks of people and projects who constellate around the Boggs Center.

MS. LOWE: We were in an organic store over on Jefferson, on [inaudible], buying food and I heard this voice and I said, “Wayne Curtis?” and went around and there he was, just a fantastic artist and a great guy. And we — in some kind of magical way, we started this relationship where their whole thing was about the garden and my thing was about houses and how we work with folks in community and try and help them to rehab their souls as well as this place.

So the story starts out that I worked for — I’m a brain injury survivor myself. And I started working for a law firm and working with disabled vets. And we started having conversations as I was trying to help them get some money. And the guys were just so down on their luck, you know, and you heard these stories of guys who came in from Vietnam, like Wayne.

MS. TIPPETT: So when was this?

MS. LOWE: This was — I started working for Anderson & Associates in 2007. And I wondered what could I do? How could I help these guys?

MS. TIPPETT: So I think, when you tell those stories of working with these guys who are so broken, right, I mean it’s just layer on layer on layer of grief and loss and tragedy, it sounds debilitating to work with that, right? It sounds like you would lose hope.

MS. LOWE: Oh, not at all, not at all. It’s the — part of my own personal transformation — I think it’s probably the transformation that anyone who has a brain injury goes through — is that you lose contact with the things that you’ve been taught and, in doing so, you become like the birds. You start to do things instinctively. So you know about the human spirit. So all I did was transfer what I already knew and these guys did what was in their spirit to do. They rose up, they rose up, you know, just by, “oh yeah, I’ve been doing this for years”. Yeah, right, OK. And the talk, the conversation, and the working, and when you stand back and say, “wow, yeah, I like the way that looks”, you know, whatever it does for a man inside to have pride in what he’s doing. And all I had to do was lay out the plan.

Because this was not the typical build. I didn’t go around, “OK, I want six bolts over there, blah, blah, blah”. Do. Let me see what your spirit is leading you to do. And then when we got ready to pick them up, it was like “We don’t want this to stop. What is this? We want this green thing, too.” So that’s how the name came about, We Want Green, Too! We’ve lost some of them because they actually have jobs. They work for the VA. They’ve gone to Florida to find family. We got one just came back from Tennessee. You know, one’s a painter. He’s going to do some training this spring. Now, not only is they standing up, but they giving back. This is how you build community. So, please, take the tour.

MS. TIPPETT: Gloria Lowe’s house is warm, full of light and restored natural wood. The living space upstairs has soaring, exposed wooden beams and a luxurious bath suite.

MS. LOWE: This floor is laid by a guy who had two head injuries in the military, two. I mean, he’s lucky to be alive and just the perfection to see him pull a line all the way from the kitchen to the living room, he’s so focused. In their art, in their creativity, and laughing, and they were like a family.

So the big to-do is really upstairs. People need to see possibilities once you’ve begun creating them because then the questions come. What is the advantage of doing this? And it’s a very real advantage if the law firm that I worked for did Social Security. If a person hasn’t worked, their check is $674.

A house this size was roughly 2,000 square feet. The heating bill in this house, heating and light, was $510. So that leaves you $160? It’s very difficult to survive off of that. The heating bill in this house now is like $272 after doing a lot of baking and stuff on the holidays. It’s a big difference. That $300 allows me to do something else.

I talked to Wayne and Myrtle because the field over here, we’re going to take that and we’re going to create a garden where kids have raspberries and some fruit they can eat and fruit trees and they’ll create their own benches and we’ll do things so that they can see a different kind of world, a different kind of life. These kids don’t know butterflies. I mean, come on. That’s kind of — you don’t know butterflies? You know, so this was a part of rediscovering who we are as human beings.

[music: “Modul 42” by Nik Bartsch’s Ronin]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Gloria Lowe and Grace Lee Boggs, and everyone else featured in this show, through our website, onbeing.org.

[music: “Modul 42” by Nik Bartsch’s Ronin]

MS. TIPPETT: Coming up, we visit one of Detroit’s universe of over 1,600 urban gardens and learn about “growing culture” while growing food. Also, more conversation with Grace Lee Boggs.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Modul 42” by Nik Bartsch’s Ronin]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Grace Lee Boggs has turned 100 and so we’re re-experiencing our 2011 pilgrimage to Detroit to soak up her wisdom. As both a philosopher and an activist, she’s long pursued the workings of social evolution. Together with her late husband, Jimmy Boggs, she was at the heart of the civil rights movement in Detroit; in recent years she became a force for renewal in the darkest days of the post-industrial city.

We found her surrounded by radiant people collectively creating what felt like a parallel universe within the Detroit of abandoned industrial plants, storefronts, and homes. Today, for example, Detroit’s urban farming movement continues to grow — there are more than 1,600 urban gardens. Again, Richard Feldman, the former autoworker and longtime community activist, drove us to one of them. His family story, as it turns out, has interesting resonance with his philosophical and economic ideas.

MS. TIPPETT: Is your wife involved in this, too?

MR. FELDMAN: My wife is — we were all raised, I mean, Jimmy and Grace have sort of been our mentors for 30 years. Janice and I have been married for 30-some years and she comes out of the women’s movement and the health movement and then has been doing — she works with parents and professionals who have kids with disabilities. In many ways, Micah, our son who has a disability, cognitive impairment, has been our teacher for so many things. It sort of fits together in wonderful ways. Jimmy wrote in 1980 something called “The Job Ain’t the Answer,” when we were trying to figure out how to organize during this period of the early crisis of the ’80s starting right over OPEC. And I never understood what it meant. It sounded good. You know, you say things and words don’t have meanings until you get smarter, I guess, or older. And Micah …

MS. TIPPETT: This is your son?

MR. FELDMAN: My son, Micah, yeah. Because of his disability — and most people with disabilities, right, 85 percent unemployment and so forth and so on, never really can be successful in America because they can’t consume or produce, yet they do have meaning as human beings, really profound meanings, right, and gifts and contributions. So it was growing up with Micah and understanding that more and more with this philosophical background that helped me understand what it meant to reimagine work and reimagine life in ways that — and Micah’s fully included.

So, often parents will speak. Janice and I will speak to parents groups, and the first question they’ll say is what’s going to happen to Micah when you die? I say, you know, 40 years ago, we wouldn’t have been in this room having this conversation. So it’s about this question of time. 40 years from now, we don’t know how he’s going to live, but he’s reaching his potential as a human being because of the Montgomery bus boycott, because of what parents are doing and all this stuff. And so you understand — I’ve had the privilege of understanding change in real significant ways and personal ways, as well as the larger social ones. And um….pull in right behind her. That’d be great.

[Sounds of driving, car doors slamming and house door opening]

MR. FELDMAN: Hello! This is Wayne. This is Krista.

WAYNE CURTIS: Hi Krista.

MS. TIPPETT: Wayne Curtis and Myrtle Thompson are the co-founders of Feedom Freedom Growers. The garden in the huge lot at the side their house supplies fresh produce to restaurants and the community. They also feed themselves with it and involve local schoolchildren.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me what you do, how you came to be doing what you do.

MYRTLE THOMPSON: Well, growing food. We had a lot of space, we had a need, and the two just went together, especially coming from his background of activism and building community. Even I wasn’t familiar with some of the things that we were growing, but it was just great to grow. So we learned how to prepare those things through the help of a chef and to start to have conversations about why we need to eat better, why we need to eat more nutritionally rich and dense food.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you grow?

MS. THOMPSON: Kale, two types of kale, three types of kale, collard greens, tomatoes, bell peppers, hot peppers, eggplant, squash, strawberries, raspberries, watermelon, onions, potatoes, herbs like cilantro, basil, parsley. We grow sunflowers, we grow — the squirrels grew some corn last season [laughs]. Let’s see, okra brings people from all over. Our eggplant brings people from Indian culture into the garden and we get recipes. The young folks, they want to know if we can grow pizza, but we can grow the ingredients for pizza. Just so much different conversation and a lot of folks who want to, once again, cook their own food are participating gardening and just trying to bring those young people into it.

MR. CURTIS: Watching the kids respond and our response when you see something grow, I didn’t know that’d look like that. You know, this is the first time I seen a transplant for sweet potatoes. I never knew where okra came from and here’s the whole structure here. One thing that I think we’re going to have to pay more attention to is what food sovereignty is or food security is. I mean, along with growing food, we’re growing culture, we’re growing community because we’re growing structure, we’re growing ideology, we’re growing a lot of things to make sure that our existence is no longer threatened because of us being marginalized in a system that’s killing us and we ain’t got no say-so in our existence or how we live as human beings. So developing consciousness, I think, is very important. It’s just not a warm and fuzzy garden, you know. We’re not just growing food, we’re becoming part of this process of existence in the whole ecology system that exists not just in the garden, but has existed since the beginning.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, this is just making me think again of something I talked to Grace about and it’s come up with other people too over the years. There’s progress that comes about by something new and there’s progress that comes about by rediscovering things that human beings used to know forever and forgot. But what you’re actually adding to that is, yes, in a way you’re rediscovering something that the first human beings learned, how to plant their own food, but you’re learning it — relearning it, rediscovering it, with consciousness. Maybe that’s the new part, the awareness of it, and making a really conscious link between about what this means to being human.

MR. CURTIS: We’re developing a humanistic practice, and Ericka Huggins said something about “the oldness of new things fascinate me, like snow”. So exactly what Grace was talking about. So we’re rediscovering ourselves and redeveloping our identity. Our identity is no longer connected to Del Monte. I love this poem: “One day I forgot name, age, sex, religion, address. I found myself.”

TRENT GILLISS: What are you seeing differently in the city now that you’ve started growing?

MS. THOMPSON: For me, it’s been different plants that grow in a season that are edible. The spaces, how many people are really growing food for their own personal use or just spaces that could be utilized on a community level, just being more aware of how nature takes care of itself and given a chance, if you leave it alone, it will rejuvenate and bring back ‘cause there are so many things that are growing wild that we could actually survive off of if we had to and that are valuable that are being sold in stores like Whole Foods for zillions of dollars a pound. They’re growing wild in lots.

MS. TIPPETT: So what are you thinking about? Tell us an example of that.

MS. THOMPSON: The red clover flower, those little red clovers that grow everywhere? Me and my grandkids were harvesting those this year [laughs]. Burdock root all over the place, mint is everywhere. I mean, just so many different herbs and vegetation that is just sprouting. Fruit trees — when I was a young girl, this city was — everybody had fruit trees and grapevines. We just abandoned some things that were beneficial to our very survival. So, those are just some of the things I’ve noticed [laughs]. And I also noticed what people are putting in their food baskets these days, so [laughs] a lot of that.

MR. CURTIS: It changes your culture because, when you rediscover like what can be eaten that’s been there all along and you drive your car over it and mow it down, when you change your oil, you throw your oil on something that’s very valuable. And now, instead of throwing pallets over something, someone will look up under the pallet and say, “You know, you could eat that.” And so that changes your relationship with the earth, but it changes your relationship with another person because when they go to drive their car over it or spit on it or whatever they’re going to do that’s negative or disregarding this life, you have to find a way to explain it to them.

[music: “Our Calvalcade of Sightless Riders” by Harris Newman]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: visiting the Detroit community of Chinese-American philosopher and civil rights legend Grace Lee Boggs. She turned 100 this summer. She introduced us to all the transformative voices we’ve heard this hour. Here’s the last part of my conversation with her in her living room, which is also the hub of the Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership.

[music: “Our Calvalcade of Sightless Riders” by Harris Newman]

MS. TIPPETT: I read you talking about models of activism, models of successful activism that have inspired you across your lifetime. Some of them people who are not famous in the larger culture, A. Philip Randolph.

MS. BOGGS: Well, in 1941, I was working for ten dollars a week in the philosophy library of the University of Chicago. I had gotten my PhD the year before, but ten dollars a week didn’t allow me to live very luxuriously. In fact, I was living rent-free in a basement. And one of the disadvantages was that I had to face down a barricade of rats in order to get to the basement and that put me in touch with the black community, which was also facing rat-infested housing.

It was July 1941 and A. Philip Randolph was calling upon blacks to march on Washington to demand jobs in defense industries because the Depression had ended for white workers, but not for black workers. And when Franklin Delano Roosevelt heard about the march, he begged Randolph to call it off. Randolph refused, Mrs. Roosevelt begged him to call off the march, Randolph refused, and eventually FDR issued Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in defense plants for blacks. That changed the life for blacks and that made me decide I was going to become a movement activist. I didn’t know what was going to happen [laughs]. I’ve been so fortunate.

MS. TIPPETT: Who else comes to mind for you?

MS. BOGGS: Jimmy Boggs, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King. Those are the three prophets in my life. Another one is Margaret Wheatley. One of the most wonderful things about Margaret Wheatley is that she has pointed out how Newtonian science and scientific rationalism has made us think of life and reality is made up of particles, and quantum physics gives us the opportunity to look at change in a very different way, not in terms of mass, but in terms of organic connections, and of emerging changes, of changes that take place at a lower level so that, as a mass level they have more permanence and more reality.

There’s something about people beginning to seek solutions by doing things for themselves, by deciding they are going to create new concepts of economy, new concepts of governance, new concepts of education, and that they have the capacity within themselves to do that, that we have that capacity to create the world anew. I mean, if you lived in Detroit or if you came to Detroit more often, you would be absolutely amazed at the people who start to create solutions to everyday problems and, in doing so, create movements.

MS. TIPPETT: One of the interesting distinctions you make, I think, is that it’s important for change agents to know the difference between the possible and the necessary.

MS. BOGGS: You know, Hegel has this section on necessity and possibility and actuality. And I think, for a long time, we radicals thought that it was only the necessary that was important, that we had to — change had to come out of necessity and that the idea of possibility is so much more complex, so much richer, but that the possible demands most of us, demands our creativity, demands our imagination.

MS. TIPPETT: It demands imagination as much as knowledge. It demands what we don’t yet know as much as what we already know.

MS. BOGGS: You know, of course, what Einstein said, that “Imagination is more important than knowledge”. He recognized that knowledge is what has happened, whereas imagination begins to open up what can happen, what you can make happen.

MS. TIPPETT: And so I want to ask you, again, the hard question, I think. Do people come back to you in a place like Detroit, in an inner city, an American inner city, and say what good is imagination when people can’t eat, when they don’t have roofs over their heads?

MS. BOGGS: Well, what’s happening in Detroit is amazing. Out of the needs that people have, some people are responding. They are creating the opportunity for us to help one another. When most people looked at vacant lots and saw only dead cats and old mattresses and rubber tires, and these women, particularly who had been raised down South and had grown food, calling themselves the Gardening Angels…

MS. TIPPETT: The Gardening Angels, yeah.

MS. BOGGS: Yeah, the angels — began to connect with young people and show them what it was like to grow gardens and grow food and reconnect to the young people with the earth, with a whole new way of thinking about life and culture. You know, we have in Detroit, what we call the “City of Hope”. Richard Feldman, who’s back there, created the term in 2007. 2007 was the 40th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s speech about a radical revolution of values. 2007 was also the 40th anniversary of the rebellion here in Detroit. And we called some meetings to commemorate those dates and we found that people were beginning — creating hope for themselves. And so we called Detroit a “City of Hope” and that began to change the way we looked at reality and Detroiters looked at themselves. It’s wonderful what naming something can do?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Well, religiously, it’s the original creative act, naming.

MS. BOGGS: Naming, right. To have — to name Detroit as a “City of Hope”, to say that our right, duty, is to shape the world with a new dream, to rebuild, redefine and re-spirit our city. That’s a wonderful message to be able to carry.

[music: “Goodbye Studio (feat. Borahm Lee & George Katsiris)” by 1er cru]

MS. TIPPETT: Grace Lee Boggs was born on June 27, 1915. She celebrated her 100th birthday this year. She is a philosopher and a civil rights leader and a founder of the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center in Detroit. She authored the book Living for Change: An Autobiography. And there’s a documentary about her life and work called American Revolutionary: The Grace Lee Boggs Story.

Richard Feldman, who showed us around Detroit, co-edited End of the Line: Autoworkers and the American Dream. On our website, you can find several of Grace Boggs’ writings on reimagining work and transforming community. And read Gloria Lowe’s essay “Turning to Instead of Against Each Other.” She’s the CEO and founder of We Want Green, Too! Wayne Curtis and Myrtle Thompson are the founders of Feedom Freedom Growers. Check out photos of their community garden in East Detroit — and some of Wayne’s artwork — at onbeing.org.

[music: “Detroit Summer” by Invincible]

MS. TIPPETT: The rap artist Invincible, whom the Village Voice calls Detroit’s “femme-emcee extraordinaire,” is another star in the constellation of Grace Lee Boggs’ world of change. Invincible teaches local kids to create relationships by interviewing people in their community. They then turn those conversations into hip-hop pieces, rapping alternative solutions to problems raised.

[music: “Detroit Summer” by Invincible]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again or share this show at onbeing.org. There you can also hear and download extended interviews with all of the people featured in this program. Again, that’s onbeing.org.

[music: “Welcome to Detroit” by J Dilla]

MS. TIPPETT: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Nicki Oster, Michelle Keeley, Maia Tarrell, Annie Parsons, Tony Birleffi, and Haleema Shah.

Special thanks this week to Detroit photographer Amy Senese for the lead image on our website.

Our major funding partners are: The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the front lines of social change worldwide, at Fordfoundation.org. The Fetzer Institute, fostering awareness of the power of love and forgiveness to transform our world. Find them at fetzer.org. Kalliopeia Foundation, contributing to organizations that weave reverence, reciprocity, and resilience into the fabric of modern life. And, the Osprey Foundation – a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Our corporate sponsor is Mutual of America. Since 1945, Americans have turned to Mutual of America to help plan for their retirement and meet their long-term financial objectives. Mutual of America is committed to providing quality products and services to help you build and preserve assets for a financially secure future.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

![Cover of Detroit Summer [Explicit]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51V2XTKTzbL.jpg)