Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons + Lucas Johnson

The Movement, Remembered Forward

Wisdom for how we can move and heal our society in our time as the Civil Rights Movement galvanized its own. Lucas Johnson is bringing the art and practice of nonviolence into a new century, for new generations. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons was an original Black Power feminist and a grassroots leader of the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

Guests

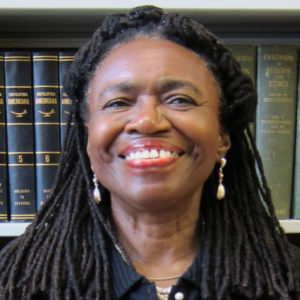

Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons is assistant professor of religion at the University of Florida. She is also a member of the National Council of Elders. Her account of her work as an activist in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is featured in the book, Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

Lucas Johnson is Executive Vice President of Public Life & Social Healing at The On Being Project. He was previously a leader of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, the world’s oldest interfaith peace organization. Read his full bio here.

Transcript

February 19, 2015

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: I can never give up on the idea that we the people can organize and bring change because we did it, and we can continue to do it.

LUCAS JOHNSON: I mean, one of the things about what we call the Civil Rights Movement that I think was so phenomenal is that folks weren’t afraid to experiment. And I feel like we’re in a fascinating time right now. I feel like I do see those experiments, so to speak…because there’s so much to be done [laughs] there’s so much to be done.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Lucas Johnson is a 30-something minister who is bringing the art and practice of nonviolence into a new century, for new generations. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons was one of the original Black Power feminists. Together, across generations, they bring little-remembered nuance of the civil rights movement into relief. It’s history I discovered I scarcely knew; a messier, more human history that reveals how much more powerful we are, than we know, to bring the great lessons of that time into practice in our own.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Rev. Lucas Johnson was born into an army family in Germany, and grew up in coastal Georgia. He is a leader of the century-old International Fellowship of Reconciliation. Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons became a leader, while still in her teens, of the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964. Today, she’s a professor of religious studies at Florida State University, and a student of Sufism. She was raised by her grandmother, who’d been a sharecropper and whose own mother had been a slave. I spoke with Lucas and Zoharah at NPR headquarters in Washington D.C. before events in Ferguson and beyond reignited racial anguish. But the perspective they offered that night has become, if anything, more necessary.

MS. TIPPETT: So, Zoharah, you tell a story about your first awakening. You described that joyful family you grew up in and you’ve described your own childhood as joyful and you were protected in many ways.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: So then you went to Spelman College. What year was that, ’62?

DR. SIMMONS: Yes. I went in ’62.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. SIMMONS: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Howard Zinn is the head of the history department.

DR. SIMMONS: Yeah. Right.

DR. SIMMONS: So I always say it was such a setup, you know, because…

MS. TIPPETT: What was a setup?

DR. SIMMONS: I mean to get there at that time and first of all, it’s important to note that my grandmother had made me swear up and down that I wasn’t going to get involved in the movement, and I said, “Oh, no. I’m not. I’m not.” And I really meant it. You know, I really did. You know, I was so glad to be going to college. And then as — you know, I was told to get myself into a church as soon as I got there. So of course, there was this big nice church right up the street which was, you know, Reverend Abernathy’s church. So I joined that church, having no idea who he was.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And then — so the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee…

DR. SIMMONS: Is right around the corner.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. And what I — I should’ve known this but I found this clarity in your writing about the particular focus that SNCC had, that it was focused on building organizations and concepts of leadership in the Deep South.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes, you know, SNCC evolves into moving from being a student-based group growing out of the sit-in movements to then becoming a group that’s borrowing in to communities and, you know, living with the people and helping to develop the leadership potential.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. You know, I mean, one thing I noticed in an essay you wrote about, you know, about your story of those years…

DR. SIMMONS: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …is you told the story about getting ready for the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And you didn’t mention the March on Washington.

DR. SIMMONS: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: Well, first of all, I certainly wanted to go.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. SIMMONS: But my grandmother wouldn’t let me.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: All right.

DR. SIMMONS: So, you know, because at that point I was not letting on that I had gotten involved in the movement. So I couldn’t tell my grandmother why I wanted to go.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: It was just like, “Everybody’s going,” and there were buses going from the various churches.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s always a very convincing reason for parents.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes. Yes. Exactly.

[laughter]

DR. SIMMONS: “Everybody’s doing it, Mom.” But she said, “No. There’s going to be a lot of trouble up there and you don’t need to go.”

MS. TIPPETT: So because I kind of want to move into the present, I want to fast forward a little bit on the evolution of SNCC.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Which was fairly dramatic.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And here’s one way you wrote it very succinctly. “SNCC evolved from a movement whose symbols was two hands — one black and one white — clasped together to one whose rallying cry became ‘Black Power’ and its logo became the Black Panther.”

DR. SIMMONS: OK. Now, you’re really kind of squishing time, right? OK.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Yes, we’re squishing time.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes, but we have to.

MS. TIPPETT: But we’ll keep talking about what it means. Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: I know, I know.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: But…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: So, you know, SNCC and me — we go through quite a bit there in Mississippi.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: So, you know, first you’ve got the three Mississippi workers who were killed.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. SIMMONS: So we do the Mississippi Freedom Summer. Many people stay on after — black and white stay on to work full time in Mississippi and other SNCC venues. Then the big thing I think that was a turning point for many of us was when the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation went to the Democratic Convention which was held in Atlantic City. This is 1964. And we had put all of our effort into organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, holding mock elections across the state, electing the delegates.

And then the Democratic Party sells us out at the convention. I mean, we were naïve to have thought that our delegation would be seated because we didn’t understand how politics worked. But it really hurt us so deeply because we were believing that we had done the right thing, and because you’d done the right thing, the Democratic Party is going to do the right thing. So I think for a lot of us, and I know for myself, this began to create a change in thinking as to wait a minute — what are we really up against here? And then you’ve got the Malcolm X phenomenon.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Right.

DR. SIMMONS: That impacts on a lot of us.

MS. TIPPETT: So Yeah. Luke…

DR. SIMMONS: So it was a lot.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s — yeah. No, we’ll keep drawing this out.

DR. SIMMONS: All right.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s pull Lucas in because one thing that I know — I heard from you when I first met you is that you grew up — one of the things that you said is that you probably heard Martin Luther King Jr. preach at around the same age that your parents heard him, but they heard him live and you heard him as history.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: And that you got a bunch of mixed messages about him and about the legacy of that time.

REV. JOHNSON: Well, I mean, it’s strange. I mean, I feel like it’s like — like I’m still in Mississippi with Zoharah right now.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: I know. We could stay there all night.

REV. JOHNSON: But I — so, yes. So my parents, you know, I grew up with — like, if there was down time in the house at some point there would be recordings of Dr. King’s sermons that were played. Or if we were driving among road trips they would play Dr. King’s sermons. And so it’s like I grew up with his voice and Aretha Franklin and, you know, like, it’s strange because I probably did grow up in some ways like I was around in the ’60s just in that little way. But, yeah, it is interesting because I think that in my generation the dominant image of — the way people would talk about Dr. King and Malcolm X was a very oversimplified sort of paradigm and it was very, I think, problematic.

I mean, many people would think of him as this — you know, as loved by white people and not a true champion for the cause and Malcolm X was the epitome of black masculinity and he was the one to really aspire to. I mean, these were not the messages from my parents but these were the messages from my — you know, growing up in the social context in…

MS. TIPPETT: In the ’80s and ’90s.

REV. JOHNSON: In the ’80s.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

REV. JOHNSON: Yeah. And the ’90s.

MS. TIPPETT: So, you and I were actually together at a gathering called Wild Goose Festival and there was a wide generational range. And I came to an event you did on non-violence, non-violent resistance, and there was a young man maybe about your age doing fabulous things in the world. And he talked about how for him the idea of non-violence, it sounds passive.

I mean, what I’ve come to understand from you and from John Lewis and others is it’s not an absence but a presence.

REV. JOHNSON: Yeah

MS. TIPPETT: And the tradition that you’re in — I also experienced you to see your lineage as even bigger and longer than the Civil Rights Movement.

REV. JOHNSON: So.

MS. TIPPETT: The Fellowship of Reconciliation. Gandhi.

REV. JOHNSON: Right. Right. So I mean, oftentimes I think about what A. J. Muste, who was one of FOR’s early leaders in the — FOR was founded around 1914 and Muste was a phenomenal pacifist. And he talked about — Muste would talk about a revolutionary pacifism, right? That was his expression and that was his way of describing this notion of direct engagement. Pacifism was not about neutrality while injustice was around you but it was about finding the courage to respond in love. And I think that it begins with a commitment to love. I describe it as a spiritual discipline, right, as something that requires a lot of internal work in order to see others as opponents but not enemies, to see others a part of the social transformation that you’re seeking to create.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

REV. JOHNSON: And so, you know, the people that I’ve learned the most from in FOR’s tradition include A. J. Muste and Howard Thurman and Vincent Harding and others.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: in conversation on civil rights and social change with Rev. Lucas Johnson and Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons.

MS. TIPPETT: The language of the beloved community as the goal was so central to Dr. King and certainly the early movement. I wonder how did the Black Power movement take up that image or wrestle with it or work with it. You know, where did this core value of love go? Or how did that evolve?

DR. SIMMONS: Well, I think that it’s important to see that this evolution — you know, it’s that the story is told and I think it’s quite true, even though I wasn’t out there on the continuation of the Meredith March. And that is the march where Stokely Carmichael, after having been arrested, stands on a flatbed truck and says, you know, “I’ve been arrested 68 times and I am not going to be arrested anymore. What is it that we need? We need black power.” And, you know, the crowd just goes- erupts. And of course this whole period has been so demonized and misunderstood historically and often people say, you know, Black Power killed the Civil Rights Movement and all of that. But it was an evolution.

You know, people don’t know that a delegation of SNCC people went to Africa after the Mississippi Summer Project and, again, they’re smarting after what has happened in Atlantic City. And then they go to Africa and they visit Guinea, they visit Ghana. And more and more, the understanding became that this is more than a moral issue. This is more than getting white Americans to love us. This is about us sharing power. And so while it was stated, flamboyantly, arrogantly, and all of that, it really was a coming to some understanding about how this country operates and that groups have to exercise power in order to get some of the things that we were trying to get for people.

And so, you know, even Dr. King said, you know, it’s one thing to be able to go to a restaurant but if you don’t have any money to buy that hamburger or more, you know, to sit down and have a nice four course dinner, it really doesn’t matter.

MS. TIPPETT: And this tension is still with us, right?

DR. SIMMONS: Absolutely.

REV. JOHNSON: Yeah. Well, it is. And I was — I mean, and I know that was a segue to the present to talk about what’s still with us, but I’m still thinking about the way that people seem not to deeply wrestle and understand with the positive identity formation that the Black Power movement also represented, right? And…

MS. TIPPETT: So say some more about that as you understand it.

REV. JOHNSON: Well, I mean,I benefit from it. I’m, you know, this consciousness that enabled African-Americans, one, to imagine Africa as something that wasn’t inherently negative, right, and to reclaim sort of a sense of afro-descendancy that they could be proud of, and that meant something.

MS. TIPPETT: Even the fact that we now use the language of African-American.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

REV. JOHNSON: Right. Right. That, you know, I mean to no longer feel like they needed to be subservient to white people or white interest and to have an internal sense of pride that was not about a political achievement, right, that was rooted in something much deeper. And I think that if we don’t understand that ,we run the risk of oversimplifying what, you know, the Black Power movement was about. In the face of the defeats of the Mississippi Freedom Summer, I mean, I — and Zoharah, you have to tell me and correct me if I’m wrong — but I see part of what the black power movement that came out of that experience is representing was an opportunity to root our struggle in something beyond a political victory. Right?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-Hmm.

DR. SIMMONS: Well, that’s a good point. I tell my students all the time and they fall out laughing, I said, “You know, when I was growing up when you called a black person an African you might get hit in the nose.”

REV. JOHNSON: It wasn’t — it was true with me growing up too.

DR. SIMMONS: I mean, this was — no, but “Africa? I’m no African. I grew up where the only movies that I saw was Tarzan. Remember? And Cheetah had more sense than the Africans.

[laughter]

DR. SIMMONS: So we have to remember what was going on.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. And isn’t it fascinating…

DR. SIMMONS: The denigration of black people.

MS. TIPPETT: …that this language that we now use all the time carries such weight.

DR. SIMMONS: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And we don’t know that.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes. And so as Lucas is saying, I mean, you know, we had a whole lot to deal with because we’re talking about a culture that has denigrated black people, made us ashamed of everything — your hair, the shape of your nose, the size of your lips. I mean everything you hate because you’ve been taught to hate. And this is why Malcolm was so amazing. You know, because he said that to us and I just, you know, want to say that in Laurel, Mississippi, you know, we had built with the community, had taken this boarded up building and built this beautiful center and the Klan firebombed it and it was burned down.

Now, I’m sitting in this partially burned out place and that’s — nobody would rent us anything else. And the mail comes. In the mail is a record of Malcolm X. I’d never heard of Malcolm. And we have a little record player there and I put the record on and Malcolm X is talking about the ballot or the bullet. And I’ve never heard anything like this. I am totally mesmerized. I’m scared to even listen to it, it’s so incendiary, you know, compared to anything else I know. But I’m so struck by it. So this is another thing that you have to know is going on in other parts of the country, that people — and so this also is seeping down into the South. And I think in many ways it was not done well. I think a lot of, you know, what came out of Rap Brown’s mouth, “We’re going to burn it down,” I mean, it was unfortunate, you know. But it was heated rhetoric and basically nobody really meant to do that but nonetheless, it was said and it was unfortunate because it frightened people. And then, you know, we have all this history to deal with without an understanding of what this comes out of, what it represents — an evolution of a people coming to a consciousness of who they are and a pride in who they are.

REV. JOHNSON: And I mean, I feel like one of the other points related to that is that I feel like when people describe Malcolm X or when people describe the Black Panther Party, they often describe what the Panthers and Brother Malcolm were saying what they were willing to do as if it was what they preferred to do. Right? I mean, they were saying we were willing to be violent.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

REV. JOHNSON: Right. We were willing to respond, you know, if we had to. But that’s very different than saying “We prefer violence.” Right? And I feel like that’s another point that gets, I don’t know, somewhere in the ’80s and ’90s got distorted or lost or something happened. But I feel like that there’s a popular conception of these movements and these folks as more violent than they actually were, right? And I think that’s another — problematic here.

MS. TIPPETT: So there’s something interesting I hear. So, Lucas, Zoharah, you’re older but you are part of this — just the Fellowship of Reconciliation. I mean, you kind of identify with this centuries-old movement that carries many of these values, the values of non-violence and social transformation before the Civil Rights Movement and into it and beyond it. And now you are bringing us even into places like Congo and Palestine today. And representing that in this country. I kind of hear you saying that you integrate all of this, including that willingness, this memory of that place that the movement got to. I mean, so that the philosophy of non-violence itself has evolved.

REV. JOHNSON: I think it’s interesting that Dr. King’s favorite scholar was Hegel, right? Or favorite philosopher was Hegel, right? Central to — Dr. King’s philosophy was Hegelian dialectic, right? This tension.

MS. TIPPETT: Thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

REV. JOHNSON: Exactly. Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: I remember that. Yeah.

REV. JOHNSON: Right? You know, so that’s, you know, Dr. King talks about a tough mind and a tender heart, right? And I feel like there are lots of tensions within non-violence, right, as a commitment, as a way of working out the struggle for justice. There’s lots of…

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a way of being rather than just withholding.

REV. JOHNSON: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

REV. JOHNSON: Exactly. As a way of being. There are lots of tensions within it and, yeah, those tensions include a tension between the struggle for justice and the commitment to love, right? They include attention between recognizing a tremendous amount of violence being acted upon someone and the desire to sort of stop that violence and the willingness or the interest in stopping that violence even while loving the perpetrators of that violence.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right, right.

REV. JOHNSON: So there’s a lot of tensions within it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

REV. JOHNSON: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. It can’t be wrapped up neatly in a bow.

REV. JOHNSON: No.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

REV. JOHNSON: No. And it’s a lot — I mean, and it’s hard, right? And I feel like there seems to be this culture I think sometimes in some places that I’ve experienced within the peace movement, particularly, of not wrestling deeply, right, with fear, with concerns, with justice. I think we have a responsibility. We have an obligation to wrestle more deeply than we sometimes do.

[music: “Goodbye Studio” by 1er Cru]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Lucas Johnson and Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons through our website, onbeing.org.

Coming up… their wisdom on how we can move and heal our society in our time as the Civil Rights movement galvanized its own.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Goodbye Studio” by 1er Cru]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today deromanticizing the civil rights movement and the models of social change it left with us. Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons was an original Black Power feminist and a grassroots leader of the Mississippi Freedom Summer. Reverend Lucas Johnson is a leader of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, which was founded in the early 20th Century. We spoke together in a public event at NPR headquarters in 2013 and we opened our conversation up for questions from the audience.

DAVID HIRSCH: It’s a privilege to hear you. I’m David Hirsch and I’d like to paraphrase Vincent Harding in the form of a question. It’s clear that you have been willing to hear the call and you are watering the seed of the trees of American life. It really grows in your own hearts. And I wonder if you could articulate the one America that you now dream and hope for.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that also gets at what is the movement now? Where are we now?

REV. JOHNSON: You know, Krista when you began you described sort of all the anniversaries that we’ve experienced and they’ve been cause for a lot of reflection for me. I mean, you know, I live benefiting from the work that Zoharah and many others did. I grew up in an integrated community. I grew up with friends from — well, one, in the U.S. Army you have this very — you oftentimes have a beautifully integrated context with white kids and black kids and Puerto Rican kids and Korean kids, and that was a part of my life. But then there was also that part of my life where I was living in southeast Georgia and, you know, I remember being confronted early on by the n-word and so on and so forth. What was different was that the power behind those insults was not the same as what you had to experience, Zoharah, and those people that called me that in the third grade became my friends by the seventh grade. And we loved each other and we were able to become friends and some of those folks I’m still friends with. Right?

But that didn’t stop Renisha McBride from being shot. And it didn’t stop Jordan Davis from being shot or Trayvon Martin. You know, I hope that what we’re working towards and the vision for the United States that has not yet been is one where certainly those things don’t happen and certainly our incarceration rate wouldn’t be what it is. And it’s hard to even see what that America would look like. It’s hard to even imagine. I know when I experience it, but to try to describe it in some big way is still hard for me. You know, in some ways maybe I’m working towards something that I can’t quite imagine but I know it when I see it, you know?

MS. TIPPETT: You know, there’s a question that arises and I feel like it’s been around the edges of some of the things you’ve both been saying about how social change happens now. You know, because it’s also hard to imagine in this world we inhabit the kind of focus on a leader like Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela. It’s hard to imagine the kind of mass movement. Even — I don’t know. Lucas, I know you wrote at some point that you sometimes felt envious of the clarity of focus that the civil rights activists and leaders had in the ’60s but, you know, when you tell the real story beneath the surface it was very complicated.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: But I don’t think a movement is going to work that way now. And I wonder how does change happen now? What adaptations do you see?

REV. JOHNSON: I mean, one of the things about what we call the Civil Rights Movement that I think was so phenomenal is that folks weren’t afraid to experiment, right? And really, I think that what was…

MS. TIPPETT: It’s kind of what you’re describing, all of that experimentation. Yes.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

REV. JOHNSON: Yeah. I mean there was lots of experimentation. And I feel like we’re in a fascinating time right now. I feel like I do see those experiments, so to speak. I do see pockets of experimentation or pockets of resistance to unjust systems or dehumanizing aspects of American life. I think that it’s probably going to be lot more, in terms of what a new movement would look like, it will probably necessarily be a little bit more diffuse, you know? Because there’s so much to be done. There’s so much to be done. And, you know, my elders, Zoharah included, for me I’ve often heard — used other language to describe the Civil Rights Movement, right? The movement for the expansion of American democracy or the southern freedom movement. And I think that the importance in that language is that it describes a struggle that is ongoing and that is much bigger than a particular political effort. Because I think that there’s an innate humanness about our problems and our struggle to address them that we have to be working at and committed to overcoming.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s take another question.

FATEMAH KESHAVARZ: Hi. My name is Fatemah Keshavarz and I think one thing that came out of the conversations is, as Krista pointed out, that this movement has been deeply spiritual. And I also hear the Dr. Zoharah Simmons has a Sufi background. And of course, for the Sufis there’s a struggle between not surrendering to resistance, even subversion, at the same time complete acceptance and love, this tension there. I wonder if when that came for you was that in an early stage? Or did it play — did your Sufi practice play any role in your role in the movement, with your own personal growth, if you care to comment on that. Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: So Fatemah Keshavarz is a very renown scholar of Rumi.

DR. SIMMONS: Oh, OK. Wow.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s such an interesting question.

DR. SIMMONS: It is.

MS. TIPPETT: And I was intrigued to hear that you were Sufi also because we know about the nation of Islam, although that’s actually such an interesting story. The nation if Islam evolved so much and I don’t feel like that story came down. But, yeah, this question of Sufism and how that played into your evolution.

DR. SIMMONS: Well, first of all, I met a Sufi master or teacher in 1971. So it was after I had become a civil rights, human rights activist. And interestingly, first of all, you know, I grew up as a Baptist in a very, very Baptist home. And all my family, you know.

MS. TIPPETT: You were just trouble.

[laughter]

DR. SIMMONS: I know, I know. So — but even early on I had questions that I now understand that were always there, you know, about who are we? Why are we really here? What is this all about? Because now thinking about it, I saw a lot of poverty and suffering. And I was like, you know, in church I’m hearing how good God is and all of this. And I’m like, well, why is God letting this happen? You know, what is really going on here? So those questions had been a part of me for a long time. But then in 1971, I meet a person. I learn about a person who his student was studying for a Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania and he needed some Americans to help him bring his Sufi master to the United States, Sheikh Bawa Muhaiyadeem, and when I heard about this teacher I thought, “Hmm, that’s what I’ve been looking for, somebody who had some insights into the, you know, these things that are bothering me and have been for so many years.”

Now, once he came and I started going and listening to him and all, I thought, “Oh, my. If I’m going to embark on this Sufi path, this journey, the inward journey, does it mean I have to give up the outward struggle?” And that was a big problem for me. And I can say I really grappled with it for quite a while. I mean to the point of tears, because the movement and the struggle was such a part of my life that I said I can’t give this up for anything. But on the other hand, what he was teaching me about the soul and why we really had come was also very appealing.

So there’s that tension that exists still to this day after all these years. I’m still grappling with those two things.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: in conversation on civil rights and social change with Rev. Lucas Johnson and Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons.

MS. TIPPETT: Another question?

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: Hi. I work in the southwest neighborhood of D.C. and one of the many things that I do is that I work with children after school. And the context that I see children coming from is, in many cases, violence in various ways. There’s domestic violence, there’s gang activity in the neighborhood, and there’s also just that their experience in a lot of ways in school and in life is sort punitive. And the kids then sort of play that out in their relationships with each other. And I just wonder what is there — what’s the practical application of the non-violent spirit in that situation? And is there anything that someone like me, who feels deeply unqualified can do. And then the other aspect of that, that struck me, Dr. Simmons, when you were speaking is that those of us in my generation and Lucas’ generation have seen kind of the Civil Rights Movement as having this kind of halo around it. But when you describe being a young student, I suspect to maybe that generation it looked like an awful lot of rebellion and fuss and trouble. And how do we channel what sometimes looks like to the establishment of our generation as, like, the rebellion and fuss and trouble of the kids coming up into this sort of non-violent social justice paradigm?

DR. SIMMONS: Wow. That’s a hard question.

[laughter]

DR. SIMMONS: And, I mean, I really feel where your question is coming from because it’s certainly something that I am deeply troubled by, deeply. And, you know, I think on the individual level what we can do and certainly what I try to do when I’m around young people, first of all, is love them and let them know that I am and you are in their corner. And to let them know that they can come to you and even though you might not be able to change the actual, you know, structures in which they are living for them to know that you love them and that you care for them is very, very important. But we also have to have structural changes and this is where I can never give up and I think that’s because of having come through the movement, having been born in the Jim Crow South. And Lucas and I were talking about this last night: How do you come from, you know, 1964 Mississippi to where we are now? And I’m not in any way Pollyannaish about where we are now. We have a lot of problems. But I never thought I would live to see the day that there would be a black man in the White House. I mean, that to me was absolutely impossible.

So, you know, there are changes even though there are so many problems still. So I can never give up that, on the idea that we the people can organize and bring change. That I just — I know we can because we did it. And because we did it we can continue to do it. But at the individual level we have to give them love. So that that becomes somewhat of a balm for the bruises, for the pains, that they are suffering. And it’s very little but I think it does help while we are building the structural changes, the institutions, that we must build, to change the reality for these children.

MS. TIPPETT: Lucas? I’m not letting you off the hook.

REV. JOHNSON: Oh, man. I was like yeah.

[laughter]

REV. JOHNSON: Well, the first thing I want to say is that you called yourself not qualified or not able and that’s not true. The second thing is I was reflecting on — you described several different layers of the problem. And I think that we have to recognize that we can’t always address all the layers at the same time and we have to focus on what we can do. I do believe that sometimes, unfortunately, our schools are more like traps than centers of education and learning. But I think that every little effort from every teacher, from every person that can give that effort will help those children along, will help your students along. And I’m grateful for teachers and particularly those teachers in my life who did that.

MS. TIPPETT: There is something very important about the perspective that’s provided. I mean, this sense that the questioner had, that I think so many of us have, of the insurmountability of the structural problems. And this feeling of not being qualified. You know, and then we look back at this monolithic, successful — right? But I mean you describe the absolute complexity and the insurmountability of the structural problems was arguably at least as great as it is now. And there’s something helpful just about remembering that. That maybe also gets lost when we celebrate the milestones, right?

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, we celebrate the accomplishment.

DR. SIMMONS: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s take another question.

LISA SHARON HARPER: Thank you so much. My name is Lisa Sharon Harper. I have a few thoughts and then I have two questions. And the first thought has to go back to our earlier conversation about Black Power and recently in our history we have three films that I think really do a beautiful job and a powerful job of explaining the African-American male’s experience in America and why that call for Black Power would actually rise out of the soul of black men. “12 Years a Slave,” “The Butler,” and “Fruitvale Station,” all three of which you just see immense, immense amount of control that are put on black men in particular.

Now, flash forward to today and we have the Voting Rights Act being chucked with the section four being diminished. We have the Stand Your Ground and Stop and Frisk. We have mass incarceration. The question is in today’s context, what can nonviolence -the non-violence strategy of the ’60s, teach us about how to engage with issues like immigration reform, like economic disparity like the president talked about recently? And then what are the ways that the ’60s Civil Rights Movement, maybe that context isn’t like this context? And so what are the challenges that that strategy would meet in this current context?

MS. TIPPETT: Take one of those questions.

[laughter]

DR. SIMMONS: Wow, right? Well, I think that we are seeing movements arise and I agree with you because the Civil Rights Movement initially was dealing with the lack of rights on the books, you know, and we’re not dealing with that now. So we’re dealing with very different things. I’m very involved with the Dream Defenders down in Florida.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I’m glad we — that got mentioned.

DR. SIMMONS: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

DR. SIMMONS: And a number of my students are leaders in the Dream Defenders. And so they are working on the school to prison pipeline and this is something that I think we need to be working on across the country because it is a huge issue. The question is how do we as people of conscience, people of faith, how do we galvanize ourselves to take these issues on? Because I believe that we are in the majority, but for some reason we are fragmented. Maybe because we have so many issues that we are taking on. How do we make an umbrella over all of these groups so that we become united in our effort to bring about the change that I believe the majority of Americans want in this country?

REV. JOHNSON: So I was going to say, one of the things that, you said so much that I want to speak to, but one of the things that I was going to mention was the fact that I think that we have to understand that our struggle is not just our own. And I feel like when you look back at the Civil Rights Movement I think one of the ways that that story is under-told is by the diversity of perspectives that came. I feel like there’s a way that, because many different organizations were black organizations, that the nuance gets lost, the diversity gets lost, because everybody was black. Right? But, you know, the brotherhood of…

MS. TIPPETT: The diversity within the diversity.

REV. JOHNSON: The diversity within the diversity.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

REV. JOHNSON: The Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters was not the same as the NAACP. It was not the same as SCLC. It was not the same as, you know, the list goes on. And you have the intersections with peace movement and so on and so forth. And I think that if you look at, you know, the Moral Mondays movement in North Carolina, for example, and you look at what was working well, it’s in part because coalitions were built and people were able to organize together. And so I feel like that’s one of the ways that we’ve got to start thinking and struggling. And, yeah, that’s my one answer to those questions.

MS. TIPPETT: I think we just have time for one more question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: I had a stroke a few years ago. But in 1970 I found a copy of Fellowship magazine, the Fellowship of Reconciliation magazine. And that issue had the statement of purpose. And I signed it and I figure when I get to Heaven I’ll know what really pacifism is. But Lucas, I just wanted you to tell how you first became a pacifist.

REV. JOHNSON: Hmm.

DR. SIMMONS: That’s sweet.

REV. JOHNSON: I — it’s been a journey. You know? In some ways I feel like I’m still becoming a pacifist. But I can tell so many sort of early stories that moved me along that journey but I think that I reached this point where I felt like there was — when you ask who is it OK to kill or whose mother deserves to grieve, you know, the answer is no one and no mother. And I think that I reached that conclusion early on. When Dr. King gave his sermon “Beyond Vietnam” at Riverside Church in 1967, you know, he talked about on one hand we’re called to be the Good Samaritan and on the other hand we’re called to transform the Jericho Road and change the edifice that produces beggars. And when I first read those words I felt a call to do edifice-changing work in the same tradition that Dr. King was speaking of. And I think that’s how I found myself on this journey. And I can tell you more stories later but that’s the best answer I can give right now.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I wish we had hours and I have pages of questions we haven’t gotten to but where we have gone is so rich. And mostly it leaves wonderful questions in the room for us to hold and live with and reflections and nuance, that’s new. I think in my work it’s become more and more important to me that spiritual life at its best is reality-based and the two of you embody it. So I want to thank you so much for being with us tonight and sharing…

REV. JOHNSON: Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: …what you know and what you lived.

DR. SIMMONS: Thank you for having us.

REV. JOHNSON: Thank you.

DR. SIMMONS: Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: Thanks for coming.

[applause]

[music: “Nevergreen” by Emancipator]

MS. TIPPETT: Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons is an assistant professor of religion at the University of Florida. She is also a member of the National Council of Elders. Her account of her work as an activist in SNCC is featured in the book, Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

Reverend Lucas Johnson is international coordinator of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation.

[music: “Nevergreen” by Emancipator]

MS. TIPPETT: To listen to this show again or to watch my entire live conversation with Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons and Lucas Johnson, go to onbeing.org. You can also stream this episode on your phone through our iPhone and Android apps or on the fabulous new On Being tablet app.

[music: “Touch Tone” by I am Robot and Proud]

MS. TIPPETT: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Nicki Oster, and Selena Carlson.

Special thanks this week to Izzi Smith, Neil Tevault, Joe Hagen, George Gary III and the rest of the staff at Studio 1 at NPR.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.