Jake Skeets

Daybreak

In a slight change to the normal format, host Pádraig Ó Tuama speaks with the poet Jake Skeets who reads his poem “Daybreak,” a poem combining Diné language with English, a poem rich with observation: of land, of growth, of memory, of place. Land is not just a tool to use for food, nor is it a blank space for human projection. In this poem, Jake Skeets reflects on an ethical engagement with land: an engagement that sees land as itself, not just for its uses.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres

Guest

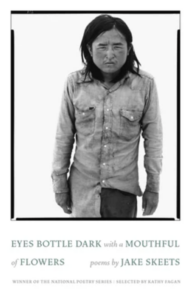

Jake Skeets is the author of Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, winner of the National Poetry Series. He is the recipient of a 92Y Discovery Prize, a Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellowship, an American Book Award, and a Whiting Award. He is from the Navajo Nation and teaches at Diné College.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I love poems of observation and memory and place. In the hands of a poet who’s showing us landscape, often what we’re seeing is what the poet sees, and what the poet sees is, a) what’s in front of them, but b) also what’s behind or beneath all of the things that they’re choosing to see. There’s memory associated with that tree, or that track. And by being brought into that, even though the poet isn’t there, they are quietly there in their reminiscence, in their memory, and in their gathering and describing of a place they’re seeing.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Our episode of Poetry Unbound today is a conversation between myself and Jake Skeets, whose poem “Daybreak” we’re going to be looking at. It’s Jake’s voice you’ll hear, reading the poem. I’ve been reading Jake’s work for a number of years and have loved the work that he’s put out and was thrilled that he was willing to come into a conversation. I was in Ireland, he was in the United States, and we recorded this conversation remotely.

Jake Skeets: “Daybreak”

“abíní hoolzish

: the low-moon horizon turquoise serenes pink-lit

from the pulp and fray of whorled milkweed

summer cypress turkey-feathered struts stark pebbled

through the sheep corral and shade house

beneath the horse trough star thistle and nine-awned grass

reflect night storms and rainbow through the morning

the sun’s rays darling through narrow shoots of cloud, vapor,

or maybe morning fog

hók’ą́ą́dóó

: above a passing plane or marsh hawk or maybe a crow

casts its wing on the sweet yellow clover and field weed

on the rubble of rust tin can and car axle and wheel barrow

a basketball backboard crafted from sheet metal and piping

the ground crickets beneath moths telling a story as butterflies

they flail and flare through two-needle piñon and ryegrass

cottontails squirrel into the culvert under the main road

now wash-like, parched, its flow sands really memory for water

i’íí’ą́ k’ad

: salsify and velvetweed overtop a broken fence

its twine, slat, and barbed wire cloaked by dusked sod

dirt road mud walls, tumbleweed, and maybe sunflowers

bow-pulled arc by the metal windmill watering faint wind

the mill echoes awake with each rock thrown

at its face, back, or the bend of its opened arms

bįįh níléíjí da’ayą́—clouds drop their shoulders into rain,

into the coral evening, into the evening’s evening”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

These poems are being composed and designed and written here on the reservation, where I currently live. So I’m back home this time, so maybe that’s the things that I see, right? I’ve been thinking a lot about my childhood home, and reflecting and visiting often, because I’m so close, and just really looking at the memories I have there and studying them and finding out new things about image.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. I’m captivated by what I’m seeing, but also, I’m in your hands, as you’re sharing what it is that you know, doing this in a way that’s just — it’s not even a list. It does feel like a symphony, or a praise song for what you can see.

Skeets: Thank you so much. And yeah, I do believe the images here are acting in unison to create this really three-dimensional view of where I grew up. And the different type of plants that are mentioned are really the result of a lot of research, actually; of going through different reports and studies that have been happening here on the reservation, specifically around where I grew up, and really identifying some of those plants that I grew up with.

Ó Tuama: Are there particular favorite plants that you have today, when you’re reading the poem just now?

Skeets: So the salsify, I think, are really gorgeous, and I have some of them here in Tsaile, where I currently live. And they grow about three, four feet high, so they’re about thigh height to me or hip height to me. And they almost look like gigantic dandelions. So I have a lot of them here, and they’re really hard to get rid of, so once they grow, they’re kind of there.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Good thing you like them, then.

Skeets: [laughs] Yeah, for sure. Yeah, but we have two right outside our front door, here in Tsaile.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Lovely.

I’d love to talk to you about Diné language, because, particularly in this poem, there’s phrases that you use, titles perhaps, and certainly, in the third piece there is a phrase within the body of the poem. Could you talk a little bit about that? And I’d like to talk, too, about your study and speaking of Diné language.

Skeets: Yeah, definitely. I feel like the poem, for me, has always been about translation, actually. The phrases I use in Diné were phrases that I have been thinking a lot about recently, in terms of just a simple kind of Diné, because I’m not a fluent speaker. I don’t have Navajo as a first language, and so I’m going through the process of really interrogating learning Diné through textbooks and some of the phrases they use and the definitions they use — they’re kind of very one-sided or very linear. And so I’m very much interested in the project of translation, where Diné is translated into what it actually is trying to say.

So, for example, in that first phrase, “abíní hoolzish” kind of means, simply, “it’s morning.” But what is the morning? What encompasses “morning”? And I feel like Diné has a lot more to offer, and so you have to use extra words in English to get to its point, and that’s where the images and layering of images really come from.

So the second phrase is “the afternoon-time” — it’s kind of just saying it’s afternoon now, and the last, saying it’s evening, and these are sort of incomplete sentences. They wouldn’t be considered a complete sentence; you’d have to talk about the subject, who’s speaking, how many people are speaking, and situate it in a context. But I really like the idea of Diné existing outside of that space and just existing as a language, as a phrase, as a poetic being.

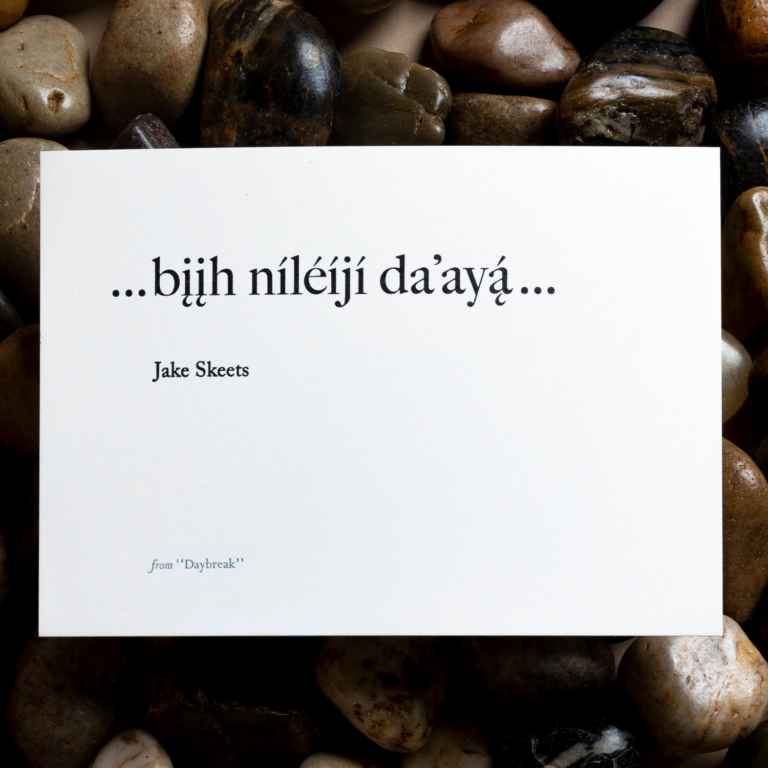

Ó Tuama: Yeah, a fragment, as well. And how about that phrase that you have in the second-last line of the final piece?

Skeets: That’s a phrase I found in a textbook. It just means “deer are eating over there.”

For me, my upbringing in Diné has always been about drills: so learning from textbooks; learning alphabets and the letters, specifically, without conversation. And so right now I’m now dipping my toes into conversational Navajo. As a young person — when I was younger, I should say, I definitely felt a lot of shame in not knowing my language. But then I began to realize that I don’t know the language because it was something that was taken from me and taken from a lot of our communities. And so, often that sort of victim blaming, where we’re the victims in this sense, and why should I feel ashamed for something being robbed or taken from me?

Ó Tuama: Yeah, that’s a real taking of a soul. It’s an old technology of colonization, is to take the soul of a people, as well as the technologies of practicalities. But the soul-robbing of it in the first instance is an extraordinary violence.

Skeets: That’s a nice way of putting it. You’re absolutely right. I feel like, not only that, but in addition, English as a language has always been transactional, rooted in an idea of capital. And so not only does it take away something inherent, like soul, it also reintroduces something manufactured, like product.

And so today, I’m a teacher here in Tsaile. So I teach my students English composition and rhetoric. And I always remind them that the rhetoric I’m teaching is foreign, that it’s transactional, that it’s rooted in dominance and destruction, rather than communication.

[music: “Vulcan Street” by Blue Dot Sesssions]

Ó Tuama: Going back to the poem, I’m so interested that there seems to be an absence of a speaker. I mean, of course, there is a speaker and a seer, because, you know, [laughs] I’m reading or hearing the poem. But there isn’t a person being narrated into it.

Skeets: That was the project for this poem, specifically, was about speaker, and how can I use Diné and English in a poem where the speaker’s not really there? That was the question I had, is how can I write a piece without the speaker?

Ó Tuama: And did you just set that for yourself, or was it part of a project with other people? I’m curious where that writing prompt came from.

Skeets: It was more so a constraint that I put on myself. This poem was initially a part of a project with Joy Harjo and sort of mapping these Indigenous poets throughout the country, here in the United States. And I wanted one where there was a different look of what it means to decenter yourself when you’re talking about where you come from. And this was my way, or attempt of doing that, at least.

Ó Tuama: And what does it mean for you, to decenter the self within the context of a poem? And why is that an important thing to do as an act of — almost recalibration about what it means to be present on the Earth?

Skeets: For me, I think it’s giving land that exists around us space to breathe, basically. Often, when we hear about the rhetoric of land, specifically through things like climate change and the end of the world, it’s always the end of us, not necessarily the end of beings and living things around us. It’s always, Oh, well, the human race is ending; therefore, the entire world is ending, when I think really, it’s about continuance and really giving space to the land around us to just exist on its own, without us at its center.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: You speak, too, in another one of your essays, about “radical remembering.” I’d be curious to hear you share a little bit about that and what that means. It feels like an artistic point of view, when it comes to questions to do with how you write, but also an ethical stance about what it means to be present in the world today.

Skeets: When we remember things, we are breaking down time. Of course, in a linear sense, that doesn’t make sense. But when we start to really engage with time and memory, we remember things from our past and our present to help shape our futures. And I think, for me, that’s breaking down time. It’s creating a time loop of some kind. And for me, that’s a radical act, to take control of linearity, to take control of systems that have been sort of forced upon us, and so that we can begin to slightly reimagine at least our own way of going about our daily existence.

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “Daybreak” by Jake Skeets.

Skeets: “abíní hoolzish

“abíní hoolzish

: the low-moon horizon turquoise serenes pink-lit

from the pulp and fray of whorled milkweed

summer cypress turkey-feathered struts stark pebbled

through the sheep corral and shade house

beneath the horse trough star thistle and nine-awned grass

reflect night storms and rainbow through the morning

the sun’s rays darling through narrow shoots of cloud, vapor,

or maybe morning fog

hók’ą́ą́dóó

: above a passing plane or marsh hawk or maybe a crow

casts its wing on the sweet yellow clover and field weed

on the rubble of rust tin can and car axle and wheel barrow

a basketball backboard crafted from sheet metal and piping

the ground crickets beneath moths telling a story as butterflies

they flail and flare through two-needle piñon and ryegrass

cottontails squirrel into the culvert under the main road

now wash-like, parched, its flow sands really memory for water

i’íí’ą́ k’ad

: salsify and velvetweed overtop a broken fence

its twine, slat, and barbed wire cloaked by dusked sod

dirt road mud walls, tumbleweed, and maybe sunflowers

bow-pulled arc by the metal windmill watering faint wind

the mill echoes awake with each rock thrown

at its face, back, or the bend of its opened arms

bįįh níléíjí da’ayą́—clouds drop their shoulders into rain,

into the coral evening, into the evening’s evening”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: Thank you to Jake Skeets for sharing his reflections on his poem “Daybreak,” from the book Living Nations, Living Words, edited by Joy Harjo. Read the poem on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.