Jónína Kirton

Reconciliation

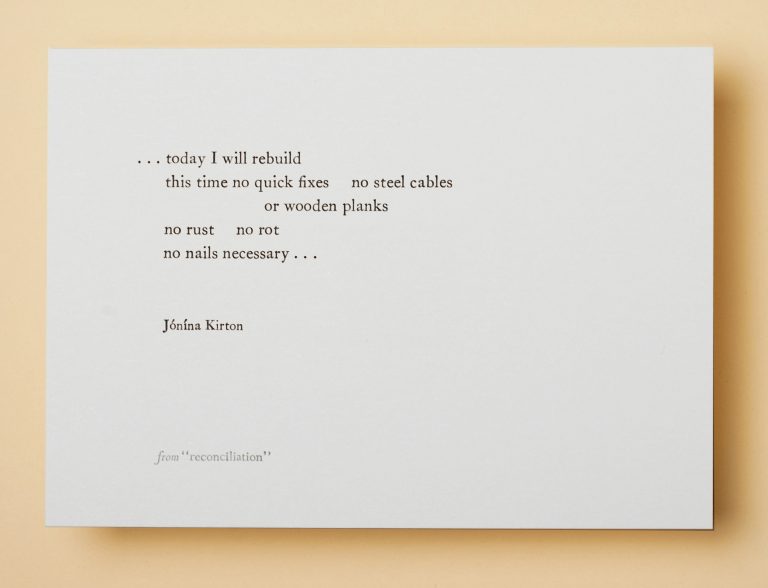

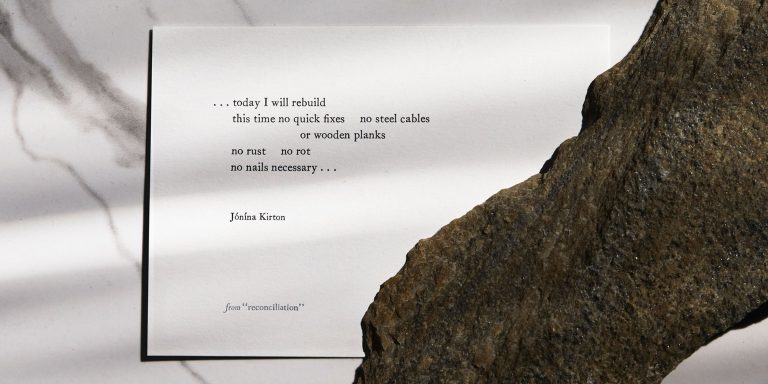

This poem starts off by describing how split the poet — Jónína Kirton — feels between two identities: having both Métis and Icelandic heritage. The poem imagines a bridge between these two places and cultures, and arrives, in the second stanza, at the image of a “living root bridge.”It is in this image that the poem anchors itself: a bridge that is part of the earth, a bridge that lives, that is not torn, but alive and growing. This metaphor speaks to what is possible in a life, and helps Jónína Kirton thrive in the tension she thought would tear her.

Letterpress art by Myrna Keliher.

Photography by Lucero Torres. Image by Lucero Torres, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Jónína Kirton is a Red River Métis/Icelandic poet and a graduate of the Simon Fraser University’s Writer’s Studio where she is currently their BIPOC Auntie supporting and mentoring BIPOC students. In 2016, she received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for an Emerging Artist in the Literary Arts category. Her books of poetry include page as bone ~ ink as blood and An Honest Woman, which was a finalist for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and poetry and reconciliation have a particular kind of relationship with each other in the experiences that I’ve had. Sometimes I think a poem might seek to bring all kinds of resolve, but reconciliation is an ongoing process, rather than something that’s reached once and then you stay there forever. Reconciliation doesn’t work as a final event—reconciliation is a continual truth telling, and there’s tension in that, rather than easy resolve.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Reconciliation” by Jónína Kirton:

“how will I reconcile myself?

the Icelander and the métis

the settler and the

Indigenous

an ally to myself

since birth flung across a

chasm

I often wonder am I to

forever be

the way across

weak anchors at each end

my spine a flexible deck

load-bearing

and within my cables too

much tension

as some try to cross

we all swing wildly

in each other’s steps

without safety nets

the waves of emotion

threaten us all

and then there are times

that both sides seek to disown

to cut my cords

let me fall to the rushing

waters below

maybe one day I will just float away

see where the water takes me

but not today

today I will rebuild

this time no quick fixes no steel cables

or wooden planks

no rust no rot

no nails necessary

but rather the slow growth of twisted roots

from ancient trees

the way across a path

made of grandfather

grandmother stones

I will become a self-sustaining structure

gain strength over time

a living root bridge that lasts five hundred years”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Jónína Kirton is a Canadian poet of Métis and Icelandic heritage. And the Métis are a distinct Indigenous group who have both Indigenous and European ancestry — “métis” is the French word for “mixed.” And also, in Canada there are particular areas, a bit north of Manitoba, especially, that have a long and distinct connection with Icelanders. And so in this poem, Jónína Kirton is thinking of her body being like some kind of bridge between Icelandic culture and Métis culture.

And so it starts off with a question: “how will I reconcile myself?” And so what we see here immediately is that we are in the body of a person who’s thinking of their joint heritages and thinking about themself as some kind of meeting place, as some kind of torn place — “an ally to myself since birth,” she says — and does that involve a certain sense of feeling split? And so within the context of that, as well as thinking of land masses between Canada and Iceland, she begins to think of a bridge.

And the first metaphor that she uses for bridge, it’s an engineering metaphor. There are anchors at each end and a deck, and questions about can it bear loads, and cables. And she says that the anchors are weak, maybe, and that the bridge might “swing wildly.” And she’s saying there’s no safety nets underneath and that deep underneath, there’s waves — threatening waves. And this is a precarious thing for herself, but it’s also a way within which she’s highlighting that some people might wish to cut the cables, a sense that you don’t belong enough to one side or the other, and there might be questions as to where do your loyalties truly lie? And this brings a crisis.

And I think the main crisis comes at the end of the first stanza: “maybe one day I will just float away / see where the water takes me.” And then it changes: “but not today.” And there’s a line break, a stanza break, even a page break in this poem, and the poem starts again, repeating the word “today”: “today I will rebuild.” And the second stanza is less about saying, “I’ll get better engineering techniques.” It is saying, “I will build this bridge by going deep into the roots of the two places.” And she uses a metaphor, really, of the living root bridges that you find in India. And she says that by going into this understanding about how deep the roots can go, by being deeply rooted in two places — that somehow the way within which those two places are held together in herself, in her story, and in her body, that that will gain fortitude by deep roots in two places.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

I see the crisis of hybridity here. In many ways Jónína Kirton is a poet who pays a lot of attention to the question of gender, the question of age — she was 60 when she published her first book of poetry — and, as well, to the question of Métis and Icelandic culture. But by being so vibrant about the hybrid nature of her ethnic heritage, I think that that probably opens her up to people saying, “You’re not one or the other,” or, “You should disown one and embrace the other.”

And that, I think, is an extraordinary thing that she circles around in so much of her poetry, is paying attention to the ways within which others might look, and what does it mean to find a voice from which you speak: a voice that owns yourself, a voice that owns your gender, a voice that owns your age, and a voice that owns a mixed-race heritage in a way that opens it up to speak with great vibrancy and defiance, from that place.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

In school, lots of people in some literature class will have learned about metaphor. An example is where Emily Dickinson says, “hope is the thing with feathers.” She doesn’t say hope is like the thing with feathers — that would be a simile. She says hope is the thing with feathers, and then she goes on to describe this thing with feathers, the little bird. And Jónína Kirton says that her experience is being a bridge. She doesn’t say it’s like a bridge — it’s a bridge. And she explores in the first stanza the way that this bridge is under strain and under threat, and she might fall off it. And she wonders, do some people want her to fall off it? And she stays with the metaphor.

In a way, what she’s done, I think, has been to take something that might have been an insult — somebody saying to her, “Choose one side or the other,” or, “You’re neither one nor the other,” and she’s felt like a bridge under strain — and she’s writing about that. This is such a visual poem. You can see the bridge. You can almost hear it straining. You can see it stretching from Iceland to Canada. And I heard her speak about this poem, and she said that she did some research on bridges and came across the understanding that you get in India that you can use the living roots of trees, trees that are on both sides of a chasm, to build a bridge. The oldest of these trees in India is thought to be about 500 years old.

And it was by researching this metaphor that the metaphor that she turned to saved her and gave her this poem here that is so rich. And the metaphor itself took her deeper into the image that her imagination had suggested. And this is good poetry, but I also think it’s good therapy. [laughs] When you’re facing a time of difficulty, how it is that you can shore up fortitude, in order to be able to face or defy that time of difficulty, is to find a way to think, what image comes to mind?

So you might find yourself thinking, Oh, that was a knife to the heart. And what this poem practices is to say, let’s ask some questions about that knife. What color was it? Was it sharp? Who plunged it into you? Who made the knife, and what could it be used for fruitfully, rather than destructively? This poem invites people to pay attention to the imaginative landscapes, to the imaginative figurations that come with language, that come with trying to experience ourselves living in the world, and the pains that come with that, and to think that maybe the metaphors that strike us can be something that contributes to my vivacity and my response and my feeling like I am not diminished — I’m determined.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Reconciliation” by Jónína Kirton:

how will I reconcile myself?

the Icelander and the métis

the settler and the

Indigenous

an ally to myself

since birth flung across a

chasm

I often wonder am I to

forever be

the way across

weak anchors at each end

my spine a flexible deck

load-bearing

and within my cables too

much tension

as some try to cross

we all swing wildly

in each other’s steps

without safety nets

the waves of emotion

threaten us all

and then there are times

that both sides seek to disown

to cut my cords

let me fall to the rushing

waters below

maybe one day I will just float away

see where the water takes me

but not today

today I will rebuild

this time no quick fixes no steel cables

or wooden planks

no rust no rot

no nails necessary

but rather the slow growth of twisted roots

from ancient trees

the way across a path

made of grandfather

grandmother stones

I will become a self-sustaining structure

gain strength over time

a living root bridge that lasts five hundred years”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Reconciliation” comes from Jónína Kirton’s book An Honest Woman. Thank you to Talonbooks, who gave us permission to use Jónína’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.