Kerry Washington

Acting as a Devotional Practice

“Becoming other people” for a living, as Kerry Washington likes to describe her craft, turns out to be a revelatory lens on the high drama that is the human condition. As a “learning actor,” a kind of actor/anthropologist, she has brought elegance and moral rigor to all kinds of roles: as the uber-glamorous, tough-as-nails Olivia Pope on Scandal; as the wife of Idi Amin and the wife of Ray Charles; from Little Fires Everywhere to Django Unchained. Just after Scandal ended seven triumphant seasons, she starred on Broadway as Kendra, a jeans-clad mother in a Miami police station waiting to hear what has happened to her beloved son. Krista was in that audience, and saw how Kerry attended not just to her role on stage but to bringing a beautifully racially mixed audience to participating and reflecting together.

So this conversation has been a while in coming. It is rich with grace and surprising angles of insight — on the roles we all learn to play in the stories of the lives that we are given, and the evolution that is possible in how we assume those characters and leave them behind and grow them up.

This episode of On Being was produced with consideration of the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike and with external legal guidance. In distributing this episode, we attest to our belief that no statements made involve promotion of struck work in violation of the SAG-AFTRA Strike Order.

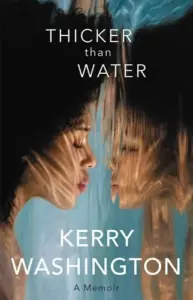

Image by Michael Tyrone Delaney, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Kerry Washington is the author of a new memoir, Thicker Than Water, and founder of the production company Simpson Street. Her many credits include the television series Little Fires Everywhere, the Broadway play — and Netflix film — American Son, and the film Django Unchained. She starred as Olivia Pope on seven seasons of the hit TV series Scandal.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: I’ve been following the actor Kerry Washington’s ethos and evolution for a while now. And when I heard that she was publishing a memoir, I was happy for the chance to draw her out On Being style. She played the uber-glamorous, tough-as-nails Olivia Pope on the Peabody award-winning TV series Scandal. That was a quintessentially American character even as it pushed at some cultural norms. But Kerry has also brought moral rigor to very different kinds of roles, including in Little Fires Everywhere, Django Unchained, and American Son. I was in the audience for that show on Broadway, and I was aware of the care and intention Kerry personally put into bringing a racially mixed audience not just into attending but into participating and reflecting together. She says to me in this conversation that she approaches acting as a devotional practice. And that is such an interesting way into the high drama that is the human condition.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Kerry Washington’s many other film and TV credits include Save the Last Dance, Ray, and The Last King of Scotland. Her new memoir, her first book, is Thicker Than Water. In it, she explores many things about which she’s not spoken publicly before. She grew up in the Bronx with two loving parents and yet in a home harboring a great deal of tension and an important secret.

Tippett: I would like to just note here as we begin a detail that feels important that you were born in the middle of the night on which the final episode of Roots aired. [laughs]

Washington: [laughs] Yes.

Tippett: Just to place your birth in time in a way that was meaningful to your father.

Washington: Mm-hmm.

Tippett: Did he really convince the nursing staff to watch in the waiting room with him?

Washington: He did, he really did. [laughs] My dad, as I share in this book, is a wonderful storyteller. He’s one of the best storytellers I’ve ever been able to witness, and I’ve learned a lot about how to tell a story from him. Although I am really good at ruining a joke, and he’s not, he’s a storyteller and a great joke teller. But he was so excited about that final episode of Roots that he convinced the nursing staff — So in the delivery room, it was my mom and the doctor, her OB. [laughs] Luckily, I was born at 1:44 in the morning, the next morning. So they were there for the most important parts, but in that earlier labor, she was on her own with the OB.

Tippett: That’s funny. Well, so perhaps this next question won’t surprise you, but I am curious — and there’s really no overt mention of this in this book you’ve written or in other things I read — I’m really curious about how you would think about the religious or spiritual background of your childhood, however you define that now.

Washington: I’m just having a moment because I’ve heard you ask this question to so many guests. [laughter] I’m waiting for your amazing guest to answer. I’m like, “Oh, it’s me.” [laughs]

Tippett: It’s you.

Washington: Okay. So one would have thought that I would have prepared an answer, but I haven’t. So I grew up going occasionally to an Episcopal church. My mom was raised in the Episcopal Church because my grandmother was Anglican, Episcopalian from the Caribbean, very Jamaica, so very British culture in Jamaica. So the Anglican Church, the Episcopal church was really important to my grandmother. And we all, myself and my cousins, my aunts and uncles, we went occasionally. There was a church that we belonged to, St. Andrew’s Church in the Bronx. And we didn’t go every single weekend, we went in fits and spurts throughout my childhood, we went on important holidays, and that was kind of the spiritual framework. We also said Grace at dinner. My dad or whoever, if it was a large gathering and there was a more senior member, it was offered to that person. But more often than not, it was my dad doing grace, at small meals, big meals didn’t matter.

And that was kind of the framework, we weren’t a very religious household. We weren’t a very spiritual household but we followed religious culture and rules. There wasn’t a lot of swearing. Although there were these exceptions. Even when I was a young child, I would have to look up the exact year, but I was definitely not in my double digits yet. When Whoopi Goldberg did her one-woman show on Broadway. And I was obsessed with this show and I memorized it from front to end. And my mother used to let me say all the swear words because that was art. [laughter] But outside of that, you know you don’t say the Lord’s name in vain, and there wasn’t a lot of cursing. And we were gently, mildly religious. Gently, mildly Christian. I did, however. have a godmother, I still do have a godmother, my titi Angela, who is a santera. So she was a priestess in Santería, which is a really beautiful religious practice, belief system that’s kind of a combination of Christianity and indigenous African traditions. And so there was a lot of openness and open-mindedness around what religion looks like and is, but it always kind of had a Christian lens.

Tippett: I have come to say that my lens on everything is the human condition. And for me, the great spiritual traditions are, as much as they’re asking about what is beyond us, they’re also asking about what it means to be human. And as I was reading you and watching you and delving into the body of your work and other interviews you’ve given, really felt to me like from a really early age — And you’ve said it different ways. You said it this way in your commencement speech at George Washington University in 2013, you said, “From an early age, I was fascinated with people and how we become who we are.” And it really has started to feel to me like that is a thread that runs all the way through, and that I kind of want to pull all the way through this conversation. How you’ve gained wisdom about that and worked with that as a human being and through living with your craft of acting. Does that make sense to you?

Washington: Absolutely. Absolutely. I love that idea.

Tippett: And just to begin in childhood, which is that soil of everything that follows. I want to read a little bit from your wonderful book, Thicker Than Water, this memoir. And to me, this passage is an example of this very strange and mysterious thing about story, which is that it can be when we speak with the greatest vividness and honesty out of our own intimate experience that we also speak to universals. So this feels like this kind of passage to me, so I’m going to read this.

“When people ask [me] if I am the first actor in my family, I often joke that I am just the first to get paid for it. There are no other [professional] performing artists in our family tree that I know of, but we — my mom, my dad, and me — are a family of performers. Each of us has spent a lifetime playing a role vital to our shared narrative. My role in our performance came naturally because I was born into its twists and turns and draped in its masks and costumes. We three were the picture-perfect presentation of ourselves as we wanted to be perceived not only by the outside [world], but by each other. We were a fairy-tale portrait of success. And this was the only show I knew — we performed it all day long, and for years. This script was how we avoided pain, messiness, and discomfort.”

That’s an astonishing passage because it’s about you and it’s about all of us. But would you say a little bit about what was that role you took on and what that made you inside as you’ve continued to live into again and work with and evolve?

Washington: Wow, what a great question. So I guess I would say the role that I was born into was a role of support. It was a supporting character in the story of my parents’ lives. And in a lot of ways for me, writing Thicker Than Water has been my attempt to step into the role of lead character in the story of my life. And so to be the right kind of support in their journey, I was always looking to support the narrative that held them up, that held our family up. This idea of Black middle-class success and intelligence. And we were a family that purported to — and not even purported — we were a family that really enjoyed culture, and we held a place in the community that was one of service, and generosity, and leadership. There’s a sense of elegance to how my family walks through the world.

And all of those traits were kind of handed to me unconsciously, and I danced along. And it felt at the same time, both very, right. Like I thought, “These are our roles, these are our proper roles.” And there is a difference between the role and the being. So I always knew that it was a role, and we felt very well cast in these roles, they were right for us. But there was more, there was something underneath it, some kind of raw humanity that was underneath the mask.

Tippett: Yes, the internal drama. [laughter]

Washington: Yes, yes. And that part I was more confused about and didn’t understand as much because to me, they almost never took off their masks. Or they only took them off late at night when they thought I was asleep or in the other room and didn’t know that I could hear. So I definitely didn’t know who I was behind my mask.

Tippett: Yeah. Let’s say your parents are still married, is that right?

Washington: They are, they are, 51 years.

Tippett: 51 years?

Washington: Mm-hmm.

Tippett: And yet that marriage — well, all marriages are complex — but it was quite a dance and a duel. And as you say, you write about experiencing it in the night. You wrote somewhere about later that you recognized there was this hyperventilating little girl who lived within you who was probably formed in that way, in that time. Is that right?

Washington: Yeah, yeah. I love letting people know that my parents are still married and that they have a really beautiful relationship. It took a long time for me to learn that, although it was my whole life, it felt like when I was a young child in my single digits, that it felt like my whole life they had been fighting. But even my whole life was a small fraction of their relationship, that there were many years before me and there were going to be many years after my maturation, my leaving at home. And that every relationship, every marriage has its ebbs and flows, and its peaks and valleys. And I think our relationship, the three of us is so much closer and more intimate and beautiful and honest than it’s ever been before. But I would dare to say that their relationship with each other is also more intimate and honest and open and beautiful than it’s ever been before.

Tippett: Yeah. You did an interview with your mother, what was that for?

Washington: Oh, a long time ago.

Tippett: You talked about Simpson Street production company, which you created, right?

Washington: Yes, yes, yes.

Tippett: Which is named after the street in the South Bronx where she grew up. And that’s was such — it was really beautiful to watch the interaction between the two of you. And she does seem extraordinary, Dr. Valerie Washington, a professor of education.

And so all of this, it’s complex, the way life is complex and the way families are complex and the way marriage is complex. And there’s so much also that’s beautiful and redemptive about it and none of that cancels each other out…

Washington: That’s right.

Tippett: …I feel like you really bring all of that into relief in that way.

Washington: Thank you.

Tippett: One thing you said about her is that she — gosh, the life she lived. Becoming a professor when for such a long time, perhaps much of her career, in many of her academic situations she was the only person of color. And you said that she was at once warm and reserved. I like that language you use of elegance because I’m not sure you used that word, but that absolutely comes through and I saw that, I saw her on YouTube with you. And you said that she was warm and reserved and that perhaps was part of the role that was given to her…

Washington: Yes.

Tippett: …to carry what she was carrying. But you were never reserved, it doesn’t sound like. [laughs]

Washington: No, my poor mother. [laughter]

Tippett: And that helping you into children’s theater companies was part of her giving you what you needed I think.

Washington: I think so, but I think that was sort of God’s sense of humor. She had really learned how to be this elegant, stoic woman, and then she had this child and I was like a walking id. I just was like one big feeling after another. And I’m so lucky that because she was an educator, because she’s such a generous spirit, because she has been such a brilliant devoted mother, her instinct was not to say, “Stop having feelings or go sit in a corner and shut up.” Her instinct was to say, “Let me find a place where you can explore all this humanity and do it in a way that I’m not in charge of having to help you navigate that.” And so I learned to be able to have big feelings and be really expressive on stage. And I knew that it was welcome there and it was rewarded there.

Tippett: And when you went to the Spence School, that also coincided with this becoming, really, part of who you were, and didn’t you get an agent also when you were already in school?

Washington: I did in that time, during my years — in middle school at Spence.

Tippett: In middle school. You speak of yourself as becoming kind of an anthropologist and very actively and intentionally as you actively and intentionally became an actor. And I find that such an interesting word and it’s so interesting to hear how that manifested.

Washington: Yeah, yeah. I guess I was really lucky that my parents are so geared toward academic success because I really have always seen myself as a learning-actor or as a student-actor. The way you talk about a student-athlete, I’ve always seen myself as somebody whose commitment to academics was as important as my commitment to the arts. And at Spence, I was really given room for that identity and that approach to flourish. I remember we were studying Hamlet while we were doing Hamlet. And for my final paper, I was allowed to keep a diary as Ophelia.

And so I had this diary that became more and more insane and deconstructed. I even figured out how to have the handwriting look more and more crazy as she lost more and more of her faculties. And so that kind of idea of approaching the work, not just in a creative play way, but in a way that called on my intelligence and my critical thinking and my ability to do a deep-dive on larger themes and on specific details. And to really, really excavate the truth of a character and of a narrative, that started early for me.

Tippett: I was just writing down some of the examples, and there are lots, you do this with every role. Even in your junior year at George Washington University, you were playing a frog and you studied frogs. [laughs]

Washington: Yeah, we did, we went to the zoo, which is part of the Smithsonian. [laughs] We went to the zoo, myself and another castmate, and we observed. We got to meet with the experts in the amphibian house and we observed the frogs. And it served me, I guess I learned early on, it provided me with some physical behavior ticks that I could bring with me. [laughter] There’s a thing that frogs do with their feet, like a constant tapping and a breathing pattern. And those things, that specificity in detail really grounds the work and allows me to kind of go deeper, to really sink into the role.

Tippett: Here’s another one. When you did this movie called Lift, you actually did some shoplifting.

Washington: I did. [laughs]

Tippett: To have the experience for which you later in your way — very subtly without confessing to your crim — atoned.

Washington: Yes. [laughs] When I look back now, I think what I was chasing was truth. Because I grew up in a household where on some deep level, I felt or knew that there was some truth that I was being protected from, or some reality that was being kept from me. And so I think I became a heat-seeking missile for honesty and for truth in performance, in life. I always wanted my work as an actor — I want not wanted — I always want my work as an actor to feel like it’s full of the truth of humanity and as specific as possible. Because those moments of vague omission or vague disconnection, it was terrifying for me as a child. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, but I just had a sense that I didn’t know everything I needed to know. And that dis-ease was, I think, part of what laid the groundwork for what I hungered for in life and in my work.

Tippett: Again, what you just said, so many of us could have our version of that. And it’s so fascinating, the particular way and the particular craft into which you channeled this. And your role as Olivia Pope in Scandal was a real breakthrough. It was a breakthrough show itself on several levels in terms of it was a moment in social media where the show was ahead. And workplace fashion, and women in the political process, all kinds of things. It’s also pretty unbelievable to me to take in that at the time of this premiere, you were the first African American woman to star in a network TV drama since 1974, 38 years, that is shocking.

Washington: Yeah. And so I was, I think, 36 at the time, so it hadn’t happened in my lifetime, so I hadn’t seen it. That idea of, “If you don’t see it, you can’t be it.” I wasn’t sure if I could be it because I hadn’t seen it. And it was so exciting and also terrifying because I felt the pressure of what everybody at the time described as a risk. The risk of putting a Black woman at the lead of a network drama. And I knew that if we weren’t a success, that it could potentially be another 40 years…

Tippett: Now that’s heavy.

Washington: …before anybody had that opportunity, yeah. But looking back in success, it’s thrilling because we were a success. And it wasn’t like we were such a great show, we were a success, it’s also that audiences were ready for it. I do think we worked twice as hard because we knew what we were up against historically and culturally. But audiences were ready, people were ready to either see somebody that looked like themselves in this space, and audiences were ready to see somebody that wasn’t who they were in this space. And so we were able to pull in audiences that were hungering for representation, or hungering for inclusion and diversity, and ride the wave of that moment. And I’m so grateful that our audiences showed up for us in that way. And that when you look back, it was because we were a success, it led to so many other shows with Viola Davis and Priyanka Chopra and Taraji P. Henson. Suddenly it was no longer a risk to put a woman of color as the lead of a network drama, and I’m really proud of that.

Tippett: Yeah, that is something to be proud of. That must be incredible, now, as you say, in hindsight…

Washington: In hindsight.

Tippett: …looking back in success to be able to say that.

Something else that you write about, and again, this comes back to this is your way of mining what it means to be human, and what it means to be you, and how we become who we are. And you’ve said that every character that comes into your life, you learn something about yourself. How would you talk about how you became more Kerry Washington as you became Olivia Pope?

Washington: Well, I think — it’s so funny, I said earlier in the interview that in many ways this time in my life in writing this book has been my adventure in learning to put myself at the center of the story. And, in effect, me being the lead character in the drama of my life. And I think playing that character allowed me to do that because I had spent a lot of my career playing a supportive role. I’d played opposite two men who went on to win the Oscar for best leading performance.

Tippett: You’d played Idi Amin’s wife. You’d played Ray Charles’ wife.

Washington: Yeah. So I had sort of maxed out on this supporting role of really pouring myself into uplifting and highlighting and amplifying somebody else’s performance, and in a really beautiful way that I’m super proud of and very grateful for. But when I stepped into this role on television, it was a different kind of responsibility. I was now number one on the call sheet, and the buck stopped with me, and I was team captain. And so when the show ended, I did find myself in a place where I had learned to be number one. I’d learned to be more of a leader, not just as a character on the show but also on set in terms of leading our cast and crew. So she taught me a lot about that. She also taught me a lot about family.

Tippett: Olivia Pope, is “she”?

Washington: Yes. About family and about committing to people and about chosen family and finding the places where you belong. And then there was this element that I never quite understood around the complexity with the father role. And I struggled with knowing exactly what it is the character was trying to tell me about my relationship with my father. But I feel like that gift came after the show.

Tippett: Say some more about that, how did that come? So this is kind of planted in you, but then it continues to develop even after the role has ended, is that what you mean?

Washington: Yeah. I have in the notes of my scripts, I have all these annotations when I’m working on scenes, it’s like, what is the theme that’s being explored here about the father? What are the questions about the father? Why am I asked to put my father’s needs before my own? Why is my father’s truth trying to override my own? There were all of these dilemmas, and I couldn’t quite, as I often can, I couldn’t quite understand why those questions were being asked of me, Kerry. But when the show ended and my parents gave me some information about myself and my relationship with my dad, I suddenly realized that there were these themes that needed to be explored.

Tippett: So you’re saying something in you intuited, so you could not have that answer you were searching for…

Washington: No.

Tippett: …but you knew there was something you didn’t know.

Washington: Mm hmm. That’s right.

Tippett: So do you want to say why that was?

Washington: Yes, yes, okay. [laughs] One of the gifts of getting this new information was that I feel like I’ve been able to heal more of my relationship with my intuition and my knowingness. Because I had these vague notions that something was being kept from me, that I didn’t know the full truth, that there was some complexity to the relationships that I was being protected from. I never knew what it was, and everyone around me was acting like that wasn’t true. And so when it was confirmed that there was a big reveal, that there was information that was being kept from me, I felt empowered. I felt like I was being given a pathway back to my knowingness and back to my instincts. So my parents — I guess over five years ago now — they sat me down. They texted me and told me that they needed to talk to me.

Tippett: Was this right, that you got this text and you had just finished filming the last scenes from Scandal?

Washington: It wasn’t right — we had just finished, it was about a month after. And I got this text and I went over to see my parents because that’s not really the language of our family, we don’t sit down and have serious talks often. And they informed me for the first time, I think I was just over 40, that my dad is not my biological father. And it was both shocking and also it somewhat crystallized some sensibility that I had but could never really articulate or understand or know.

Tippett: A relief, in a sense, of knowing that you were right, at least that there was something that you didn’t know.

Washington: That there was something, yes, there was a sense of relief. And extreme curiosity, profound curiosity, and excitement, also. And then there was also then a sense of betrayal and there was some anger and some sadness and disappointment. But all of that has been framed by this curiosity and gratitude to be in truth finally.

[music: “Forager” by Sanctus Audio]

Tippett: Something I’d like to talk to you about — I don’t interview for On Being many people who are incredibly famous. [laughs] We’re really low, I go light on celebrity. And there are many reasons for that but part of it’s just is that people who are celebrities get interviewed a lot. [laughs] So I try to have this space where we’re doing something different. So in this sense — and you’re somebody I’ve followed, and I’ve met you, and there’s this thoughtfulness that I’m really excited to pursue — but I would like to ask you about this matter of fame and celebrity, because you write about this in the book too, and it’s something that I feel like we hardly know how to talk about culturally. Even though, almost to a one, we participate in this cultural drama of celebrity, we co-create it. And I’m curious because as I say, I feel like you’re a student of the human condition as much as an actor and you happen to have become a celebrity. So are you willing to talk about this a little bit?

Washington: Yes, yes.

Tippett: So for me, I have this minuscule experience of this, of…[laughs]

Washington: In my house you’re super famous, Krista, but okay. [laughs]

Tippett: …when people know me, it’s probably my voice that they know. And even so, when I get recognized, kind of out of the blue, I find it really jarring. Because also there’s something weirdly dehumanizing about it because they feel intimate with you. Often people don’t tell you their name, they know your name. But it has occurred to me as I’ve had that just tiny echo of an experience you’ve had, how jarring it would be for it to be your face that is known. And you actually tell this really heartbreaking story of getting an abortion. How old were you when that happened with a made-up name?

Washington: Yes. I was in my twenties, my mid-twenties.

Tippett: And you’re there in the room, you’re not there with your real name, understandably. And the nurse tells you that you look like a movie star, and she says your real name. And you wrote, “That girl from the movies. That girl from the magazines. It was my name, but the version she was calling out had nothing to do with me. And so, in that moment, I didn’t know who I was. Or where I stood. I only knew that my name belonged to public spaces in a way that made privacy unavailable to me.”

Washington: Yeah, I think it’s one of the things that I felt really drew me — I don’t know if I’m allowed to talk about this because of the strike. I know, let me think about how we can do this.

Actually, it’s funny. This theme of loss of privacy has come up in my work at different times. And I think one of the reasons why it was important for me to tell that story in this work is because our right to privacy is so under attack in this larger way as women.

Tippett: In general.

Washington: Yes, our right to our bodies, our right to privacy and information. Our right to privacy is dangerously under attack. And it’s something I think we all need to be thinking about, how important it is that our lives belong to us and that we be given the space and dignity to make choices that are right for us, and that are nobody else’s business. It feels like a contradiction to say that as I write it in a book that’s going out into the world. But it’s to say that was one of those moments where I understood the value of something because I was losing it.

Tippett: And you also are really honest about this irony. On the one hand, you’re playing Olivia Pope who is flawless, [laughs] flawless in her physical being, and everything that wraps around her is flawless. And then at the same time, you’re losing your anonymity and you’re becoming more self-conscious. You describe experiences of becoming more self-conscious about how your body looks and the way it’s presented and projected after you’ve had a public appearance, after images have been published. And I just think about that hyperventilating little girl, because she was still inside you. This experience that you have is part of our life together also. I just don’t know, I just kind of want to name that and I don’t know if there’s anything else you would want to say about it but.

Washington: It’s interesting, for me, this is a very different moment for me. I’ve never done a series of interviews where the topic of the conversation is a story that is my story. I’m very accustomed to talking about a movie or a television show or a play, and to unpack that narrative and pull on the threads and the themes because I may feel aligned with them, but it’s not exactly me. This moment is really different because I’m talking about me, and it is a part of fame that I have really rejected. I have been so careful to maintain my privacy because I’ve had moments like when I had my abortion or I had a very public engagement that ended. And I found myself unable to control the flow of information, and so I thought, “Okay, going forward in my life, I really want to make sure that I’m keeping my private life private.”

Tippett: I feel like what I’m saying is that as you open up the fullness of yourself, you’re also reflecting on this weird thing that has come with the particular gifts and profession that are yours. And yet, as I say, it’s something that our culture — that we all partake in.

Washington: It’s so true. It’s funny because I talk about how at first, for me, acting became my love at first because I got to be other people. Because I could escape myself, I could escape my feelings of loneliness, my feelings of disconnection, my feelings of identity confusion. But then as I progressed through my career, I realized that acting was actually a safe place to reveal myself because I could reveal some of my emotional truths, and my beliefs, and my struggles. I could reveal them behind the mask of a character. I could speak my truth, and you thought that it was the truth of the character, even though it was my truth coming through her. And so then this feels almost like the third phase in my evolution of my relationship with myself as an actor, that I first came to the characters to lose myself. I then came to the characters to express myself, and now I’m expressing myself and my relationship with the characters, but I’m truly without the mask expressing myself. And I didn’t come to acting to do that, that feels like a byproduct of celebrity that I even have the opportunity to do it. Now that I know my story, I am less afraid to step into this role of being in the public eye as myself.

Tippett: Right. And I do feel like this intentionality that I see, that runs all the way through you as a human being from a very young age and that you brought to acting also has equipped you to get to this point so that where this celebrity thing might — the fame can be so dangerous. And you talk about — and I don’t know if you’ve talked about this before, you write about issues with food and exercise — and that this can really be dangerous for people, but you’ve really lived your way into this place. You’ve even said, as you study a character you take on, you actually try to take on their good habits and make them your own. And you wrote somewhere, “One role at a time, they were saving me.” That’s just so fascinating to hear about.

Washington: Yeah, because I felt like I didn’t have healthy boundaries. I know that’s such a buzzword now, but I didn’t have enough sensibility around: what were the structures and disciplines that were right for me. I didn’t feel empowered to know necessarily where I began and somebody else ended because I was always in this sort of people-pleasing, perfectionism, wanting to be who somebody else needed me to be. But a character became something to devote myself to. My acting was like a devotional practice where I could say, “I am willing to submit to the structures and disciplines of this narrative, this role, to get to the best possible performance, the best possible truth.”

So I could wake up every morning and run when I was doing a movie, playing a shoplifter where I had to run for the last 10 minutes of the movie and I knew that that’s what was required of me of the role. But when the movie ended, I wasn’t enough. I didn’t feel like I was enough of a reason to wake up and run. I needed these characters to inspire me to move toward goodness, greatness, excellence, purpose, maybe, is the right word.

It’s funny because I think that’s the part that was missing. When you asked about my upbringing and where spirituality fits into it. It was actually my relationship with food and with my body, that was the first thing that got me on my knees. My first experience with real prayer, like really begging some power greater than me to help me out of a situation that felt bigger than me. My first experience with that was around food because I felt so utterly powerless to make loving decisions and to really not use food and exercise as a weapon. And so that was my first intimate relationship with Spirit was part of my recovery around food and exercise and body dysmorphia.

Tippett: Thank you for that, for offering that. I don’t want to finish before we talk about other kinds of roles you’ve had that feel really important to me in terms of how you channel, and also invite the human condition through acting, and how you’ve evolved as a person. Who Kerry Washington is in her fullness. So of course, there’s Little Fires Everywhere, there’s Django Unchained, and there’s American Son, which I was so fortunate to see you play on Broadway, which also became a Netflix show. And I just want to give a little synopsis just for people who aren’t familiar with it. Now, when was that started on Broadway? What year? It was pre-pandemic?

Washington: It was pre-pandemic. It was right after Scandal. So I want to say, oh gosh, I don’t know the year, maybe ’19. I think it may have been 2019, 2018 or 2019.

Tippett: Those pre-pandemic years that now feel like ancient history. [laughter] So right, it was right after Scandal, and there you are on stage for all but three minutes of an hour and a half wearing jeans. I didn’t see that you were wearing makeup. It could not have been a different character. It’s at a Miami Police Station. It says “…on a day this coming June.” Your Black son, Jamal, has not come home, you know vaguely that there’s been some incident with the police. It’s a Black mother and a white father, and a Black policeman and a white policeman. You are that mother in center point, Kendra. Tell me that same question I asked you about what did you learn from Olivia Pope about being Kerry Washington? What did you learn from Kendra, what did she teach you?

Washington: When I was doing those amazing seven seasons of television, in the course of that time, in my off-season, in the couple of months off that I had every year, I began to build my own family. I got married during one hiatus, I gave birth to two children during different hiatuss, all during the course of that show. But the character never became a mother. And that was a conscious decision on the part of our showrunner, Shonda Rhimes. It was one that I struggled with because my body was changing as I was carrying another life, building a brain and limbs. And I felt the pressure to remain, as you described her, flawless. And there was this really challenging tension between who I was in real life and who I felt the character needed to be. But it was important to Shonda that that character not become a mother. In fact, I had the first on-camera abortion procedure in the life of our show, because my character was so committed to not being a parent.

So when the show ended, I found myself really gravitating toward material where I could explore the vulnerability of motherhood. Because what I understood was that that character was a fixer, she was the most powerful person in almost every room. And there is an inherent vulnerability in being the parent of a Black child that you cannot escape. So she would have been less of a superhero if she had become the mother of a Black child. And I say particularly not a Black mother because I’ve had this conversation with white women who have adopted Black children. It’s a specificity around raising a Black child and the powerlessness that you feel up against these systems that are created to limit and destroy your child.

And so it was a real gift for me to be able to take on a play like American Son, where I could really put myself on stage and swing the pendulum in the opposite direction. Not be the most powerful person in the room. Actually be the person with the least amount of power and agency. And to embody all of the vulnerabilities of what it means to parent a Black child, to step into the worst nightmare of what it means to be the mother of a Black child. And even to explore the other side of what it’s possible an interracial relationship might be like. On the television show I was living this fantasy of a white man that loved her so much, he literally created an imaginary war to save her. She was Helen of Troy.

Tippett: And was the most powerful man in the world, by the way.

Washington: Yes, exactly. But in this play, this interracial relationship was not the fantasy, it wasn’t the honeymoon. It was filled with all the complexity of what might not go right, where might you not be speaking the same language and where might your cultural misunderstandings rub up against each other so much that it leads to the destruction of a family.

So it was really exciting for me to get to explore the opposition, the underbelly, the unchartered territory of what it could mean to be in an interracial relationship and to parent a Black child. But parenthood, in general, is something that once I had more time and could bring all of the experience I was learning or the feelings I was having as a mother into my work, I really leapt at that opportunity.

Tippett: Well, I mean just that word “fixer,” right?

Washington: Mm-hmm.

Tippett: The thing that you learn when you become a parent is there is no fixing, right?

[Laughter]

Washington: That’s right. There’s a lot of witnessing, holding space for.

Tippett: And feeling like a failure, and wondering how you could have done that better.

Washington: Yes. There’s a lot of mending, and growing, and learning, compromising.

Tippett: Fixing is just not in the vocabulary of any, just to start with that. I will say something that really moved me in that Broadway theater was first of all, the play is intense and not funny but there was humor, right?

Washington: There was, yes.

Tippett: There was wry — And something that was really — and I can’t remember if I said this to you when we met briefly — but it was a really racially mixed audience, and people laughed at different things. And what I also noticed is that people would then wonder if they should have laughed differently, the different kinds of identities in the room. And what I learned from you was that a lot of your preparation for this particular role was also just really considering the experience of the audience and creating resources and experiences to draw that out.

Washington: Yes. It was the first time in the history of Playbill that they allowed us to put a discussion guide into the program so that every person who came to the play had some framework, and some resources, and some prompts, and ways to learn more and grow from what they saw. Because originally, we had created this discussion guide and resource list to just place on a table in the back of the theater for when people were leaving the show. But people were so shell-shocked at the end of the play — I would watch audiences stumble out of the play. And they weren’t stopping to pick up anything, they were barely breathing.

Tippett: Oh, so you didn’t know this, this all evolved and this wasn’t in Playbill in the beginning?

Washington: Right. We thought people will just pick it up as they go out, and it’ll be great. But we realized we have to put it in the Playbill because when you go home and you’re trying to wrap your head around what you just watched, which everybody shared was part of their experience. You’re going to pick up your Playbill and say, where do I know that actor from and wait, who directed this thing? And who wrote it? And that’s when I wanted the discussion guide to be in their hands. I wanted them to have resources, and tools, and a framework, and support already in their homes so that they had some way to process these feelings, and emotions, and thoughts that were coming up because of what they just saw.

Tippett: Also, Eric Garner’s mother came to the play. And Philando Castile’s mother came, and Sandra Bland’s sister came. And I have to ask, again, this was pre-2020 and I just wonder, we’ve been talking this whole time about how much you learn from every role you play. And just how did that experience kind of flow into these years that have come since, how is that with you?

Washington: Sometimes I think I’m just so lucky that I get to be used as a vessel for people to know themselves better and to see themselves more. And that play was definitely one of those experiences where these mothers of the movement and sisters and cousins who had lost people to police brutality: they felt so seen. They felt like the world knew them after the tragedy, but that we let them into the hearts of these mothers to know what it’s like before the tragedy occurs.

Tippett: While you’re in that waiting room…

Washington: Yes.

Tippett: …as Kendra was.

Washington: Yes. That we let people into their humanity before the loss, and that meant so much to them. So I feel that to me is one of the greatest gifts of what I get to do, is I feel like I get to be used for other people to see and know themselves more and to know how much they matter. And I guess that’s why I have so much joy and why it’s so moving to me when people are having that experience reading Thicker Than Water, because I still feel like even though I’m not playing a character, I’m seeing that my telling my story is also allowing people to feel more seen and understood. It feels like that’s the role of art, whether it’s a literary work of a memoir, or whether it’s music, or theater, or film, or television.

It is this opportunity for us to become more intimate with our own humanity and the deep humanity of somebody else. And I just feel like if there’s anything that we need in culture right now, it’s the courage and the willingness to know ourselves more and to know each other more. And to make room for the unconditional acceptance of each other’s humanity. Not every behavior, not every decision do we have to sign off and approve, but to make space for each other’s humanity and belonging, feels like I think so much of what we need.

Tippett: Yeah. So this is a camera metaphor…

Washington: Okay. [laughter]

Tippett: …as we land here — because that’s really such an incredible place to get to. I want to kind of pull the lens out wide. And I feel like you just walked us here, the role that we all are given right now of being alive in this time that we inhabit. And yes, having moved through this pandemic and the many ruptures that have occurred in these years and since, that we couldn’t have imagined a few years ago. And so you kind of as a human, as an actor, as a mother, in your calling as an anthropologist: What anthropological questions and curiosities are you holding now about stepping into this time ahead and this role that I think of as this calling that we all have to stand before this world? Yeah, that’s just a big, messy, huge question, but yeah, what questions are you holding, what curiosities?

Washington: I think this question — I didn’t even remember was in the commencement speech, so I really appreciate you pulling that forward — but this question of how we become who we are is the most important one right now, because it’s the question, I think, that will allow us to have a bit more humility around the decisiveness of where we can and cannot compromise, where we are alike and where we are dissimilar. If we have the willingness to ask ourselves, how did I become who I am and how did they become who they are? I think it allows us all to accept more of our messiness and to let ourselves be more human to understand we weren’t born perfect. Somebody who was dealing with their own trauma tried to raise us the best we could. And now with our own traumas, we’re trying to raise somebody else the best we can.

And to have that kind of gentle acceptance of each other that we’re just like these beings in process, doing the best we can with the tools we have. I think that could give us more space to be able to listen to each other, to appreciate each other, to be less afraid of each other. And I think that’s where we need to be, operating more from the messy humanity of each other and less from deciding who our enemies are and deciding who’s good and who’s bad.

We have a joke in my family that my favorite genre is a villain origin story because I love those movies where you get to see how the bad guys become the bad guys. Because the truth is nobody’s born a bad guy but very few of us.

Tippett: And it’s all that they got wounded, right?

Washington: Yes. Everyone has a wound that leads to — I love this book The Origins of You that’s all about these wounds. We have these wounds, and how we process those wounds and move forward through them is who we are. So asking that question, not taking it for granted that there are good guys and bad guys, but knowing that everybody’s good, we’re doing the best we can at varying degrees. It’s really hard to hold onto that belief with some of our members of society. But even when I think about people that I really, really, really have great fear and contempt for. Former presidents that I will not name. I think: that person was hurt, that person was hurt, that person has survived tremendous abuse. How they have metabolized it to continue to abuse others is unacceptable, but I have to remember where it comes from so that I don’t perpetuate it.

Tippett: What an incredible ending to a beautiful conversation. Kerry, thank you so much, what a joy.

Washington: Thank you. Oh, this is such an honor and such a pleasure. Even just you reading the book is such a pleasure, and really I’m so honored, so, so honored. Can I add one more thing that I’m not sure that I said?

Tippett: Yeah, please do.

Washington: I guess I want to say that for me, this learning of how I became who I am has been so important because it’s helped me connect more deeply with myself and my intuition and all the things we talked about. But also in learning that my parents kept this secret from me I was able to witness more of their humanity, their fear, their fear that I wouldn’t love them unconditionally, that they would lose me, that I would walk away. And what it became, what this truth-telling actually became, was an opportunity for me to say to my dad, “Every time that I’ve said, ‘I love you’ up until this point, it’s been on the condition of a lie. It’s been, ‘I love you’ and you’ve thought, ‘She loves me because she thinks I’m her dad.’ Whether you’ve thought it consciously or unconsciously.”

And so the opportunity of this truth sharing was that I got to say to my parents, “Now you get to see what it’s like for me to love you unconditionally. That when you told me the truth and you see that I don’t go anywhere, that I love you more, that I feel closer to you.”

Tippett: Knowing everything.

Washington: Yes. That’s the greatest gift that our family has been given. And so I think that even when we’re afraid to ask the question of “How did I become who I am, how did you become who you are?” Even when we are afraid of it, I think it’s worth taking the deep dive, because the truth can bring us to something that’s even more beautiful than what we could have imagined.

[Music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Kerry Washington is founder of the production company Simpson Street. Her many credits include the television series Little Fires Everywhere, the Broadway play – and Netflix film – American Son, and the film Django Unchained. She starred as Olivia Pope on seven seasons of the hit TV series Scandal. Kerry Washington’s memoir is Thicker Than Water.

And this episode of On Being was produced with consideration of the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike and with external legal guidance. In distributing this episode, we attest to our belief that no statements made involve promotion of struck work in violation of the SAG-AFTRA Strike Order.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Juliette Dallas-Feeney, Annisa Hale and Andrea Prevost.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable, and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.