Krista Tippett

The Mystery and Art of Living

This episode, a “theft of the dial.” Writer and traveler Pico Iyer turns the tables on our host Krista Tippett by asking her the questions. Her latest book, Becoming Wise, chronicles what she’s learned through her conversations with the most extraordinary voices across time and generations, across disciplines and denominations. An illuminating conversation on the mystery and art of living.

Guests

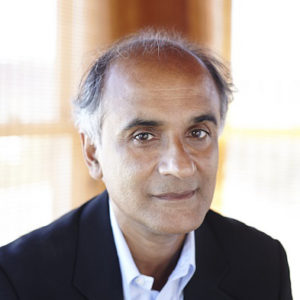

Pico Iyer is the author of many books, including The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home, The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. His latest is A Beginner's Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations.

Krista Tippett created and leads The On Being Project and hosts the On Being radio show and podcast. She’s a National Humanities Medalist, and The New York Times bestselling author of Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living. Read her full bio here.

Transcript

May 5, 2016

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MR. PICO IYER, GUEST HOST: This is On Being and I’m not Krista Tippett. I’m Mr. Pico Iyer. I’m a writer and a traveler and a former guest on this show and today I’m seeing if I can turn the tables a little by asking some questions of Krista Tippett. Krista is the author of Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living. I spoke with her recently about her New York Times bestselling book at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Our conversation was so fun and so illuminating, we thought we might share it with all of you.

[applause]

MR. IYER: One morning last year, I woke up in Orange County. [laughs] Promising beginning. And I had to fly out of LAX before lunchtime. But on my way to the airport, I had to go to a radio station for an interview that had been scheduled almost a year before. So I find myself nosing through this dystopian wilderness of mini-malls and parking lots and warehouses in Culver City. And finally I located the radio station. And I was feeling frazzled. And exhausted. Really not myself at all. And of course, worried about how I would get to the airport afterwards.

And somebody took me to a small, dark room, and they gave me a pair of headphones. And very soon, a warm, reassuring, melodious voice of somebody I’d never met began talking to me. And within maybe 10 minutes I was saying things that I didn’t even know I had inside myself. And I was saying things I might not have said to most of my closest friends.

This kind stranger seemed to have read every last word I’d ever written. She knew my thoughts better than I knew them myself. And usually when I go to a radio station, I’m told, well, we have four minutes. Or a maximum of six minutes, so please will you talk in sound bites. In this instance, we had an uninterrupted 90 minutes, and it really felt like an exploration.

And at the end of the 90 minutes, I had to tell this person I had never seen that this had been the most soulful, searching, intimate conversation I could remember having. And I think it’s the same experience that Yo-Yo Ma, and Mary Oliver, and Desmond Tutu, and hundreds of others, have all known. I think to be on Krista’s show, On Being, really changes your life by clarifying it.

And I think Krista and her guests have really become some of my closest companions, because they discuss the most essential issues with such honesty and vulnerability. But I think even more than that, what she’s really done is create a whole community of questioners and searchers. I have a friend who’s a friar of a Benedictine monastery, and he has all his monks listen every day at lunchtime to Krista’s program as a form of what they call lectio divina, a scriptural reading.

And after my show with Krista Tippett aired, I got the most interesting and imaginative invitations from Australia, and England — all over the place. It’s really a global neighborhood that she has helped to create. And I feel that she transforms the public discourse by opening up the inner landscape.

So, I’ll finally end now, but all of you know that she’s produced three books so far. Speaking on Faith takes us into her life and her vision, her work. Einstein’s God orchestrates a dialogue between religion and science. But her brand new book, Becoming Wise, is, for me, her most eloquent and passionate book yet. And it’s really a call to hope and a call to action. And it looks at how age-old issues are taking new forms and perhaps inviting new responses as we try to chart our way through this young century. So, please join me in welcoming Krista Tippett. [applause]

Of course, you know how I’m going to begin, because it’s how you begin all your shows. [laughter] And it’s a lovely soft way to begin, which is to go to the roots and the childhood of your guests. And ask them about how, as children, they first began thinking about larger things. And I know that you are the granddaughter of a fire and brimstone Southern Baptist preacher. You grew up in Shawnee, Oklahoma. Amidst lots of prohibitions, no drinking, no singing, no card playing. But you always stress that your grandfather and the people around you were lusty, and fun, and kind.

MS. KRISTA TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. IYER: And I’ve always wondered whether all of this turned you into a rebel, or whether you were already thinking, well, these are two contradictory things going on.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm. Something that’s — well, first of all, I just want to say that was — thank you for that introduction. That was beautiful. And I’m so happy to be here at UCSB, and part of this program, and with Pico. And just the way you turned the question of just pointing out those contradictions just takes me down a slightly different road. Yes. I mean, my grandfather was this towering religious figure of my childhood. And there were overt things I was learning about God from him. And God was love, but God was scary. And heaven was the place we all wanted to go, but it was kind of mean and small, right? I mean, even Methodists weren’t getting in. [laughter] And I’m not making that up. [laughter] And yet, my grandfather, in his person, was so, as you say, “lusty,” and there was an integrity about how he carried his convictions so passionately. There was something admirable about that, even if you disagreed with him. And he was funny. And he had a great big mind, but he had a second-grade education.

So, one thing that I started thinking about in the writing of the book is about how that contradictory experience of him, but also the contradictions that were alive in my family. My grandfather, I think, had a good mind, but he had never been invited or trained to ask questions. I mean, his Bible was marked up in the most amazing way. But I think questions were fearful things for him.

And in my family there were also — my father had been adopted, and there were questions that we weren’t — that we weren’t invited or permitted to ask. And so, I think that the spiritual background of my childhood was — had a lot to do with that, and I think that spiritual life, for all of us, has a lot to do with questioning. And somehow, for me, the way questions were suppressed, was painful in ways that I couldn’t understand then, but it became this pursuit of mine. I don’t know.

MR. IYER: And also, beyond that, very, very human, I think in a couple of your books you use this wonderful sentence from Reinhold Niebuhr, who says, “Man is his own vexing problem.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. IYER: And when I listen to you, I feel that religions are very either/or. But humans are much more complicated.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. IYER: In some ways, your sense of theology has — seems to have less to do with God than with man. And that’s a much bigger story, isn’t it?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And theology is as much as a discipline of — it’s a conversation across time and generations that is a much a sophisticated analysis of the human condition. And in fact, there’s a sense in which in the fields of psychology there’s an analysis of parts of us. But I think theology and philosophy really are the disciplines in our midst that have delved into this matter of our contradictoriness, and our complexity, and our beauty, and strangeness, and our possibilities. And, yes, that was such a great discovery. And it’s not what theology is known for. In public.

MR. IYER: I think in this book you write, “We are living, breathing, both/ands.” And that seems, again, so the essence of the way you see the world. And then you threw yourself out of contained walls entirely by going to live in Germany in the 1980s. And I’ve always loved the fact that you were a journalist, I believe, sending reports to the New York Timesand others. And then you were working in the U.S. Embassy. And on the one hand, you saw that great surprise of the wall coming down, but on the other, you must have seen some limitations in the public world that sent you back into the inner world.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And that’s your language, the inner world, which I love.

MR. IYER: It is. Yes, thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: I love that so much, yes. Yes. And I was focused on the outer world. The outer world as it is defined and approached by politics, which I found fascinating. And yeah, I was trained as a kind of breaking news journalist. And it was riveting. It was an amazing time to be in divided Berlin, which was really the fault line of that world, that geopolitical reality which no one at that moment guessed could vanish.

And in the last years of my time in Berlin, I was literally sitting — I was working for an Ambassador who was a nuclear arms expert, and literally sitting around these tables where people were moving those missiles around on a map of Europe. One thing I started to experience that I eventually would have some moral questioning about — I was so idealistic, I thought we were really there to save the world. And make the world a better place.

There was this very puzzling and unsettling disconnect between — I was with people who had very large outer lives. Like very large public lives, public persona, you know, people who could give brilliant speeches on nuclear weapons. But I was up very close to that and I also saw that these same individuals could have these tiny, impoverished inner lives, right? That they had poured all of their energy, and their effort, and their accumulation of knowledge into the outer world. And I think that that was also true of the 20th century, that the 20th century didn’t take the inner world very seriously, right? Because it is messy. It’s all this both/and, and we kind of thought we could bracket it out and move beyond it, maybe.

MR. IYER: Yeah. Yeah, I know Meister Eckhart has the wonderful line, “If your inner life is rich, the outer work will never be puny.” But it doesn’t work the other way around, if your outer life is big, your inner life may shrivel. So you have to start with — and that’s probably why you went straight from Germany in the middle of the Cold War, to Yale Divinity School. And I was actually thinking today the coming down of the wall is a perfect metaphor for everything you’ve been doing ever since. It’s perfect that we witnessed that, because it’s bringing down the divisions between people and finding the common ground.

MS. TIPPETT: Wow, I never thought about it that way.

MR. IYER: No, nor did I until today. Even though I’ve been listening to you for all these years. And when I read your books and when I listen to your programs, the kind of words that come up again and again are “doubt” and “surprise.” And I feel that both of those must be really important to you. You mentioned the surprise a minute ago of the wall.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. This is a bit glib, but it’s still true that the only thing in fact that is certain in life is that the next thing that happens will surprise us. I like the language of surprise maybe even more than doubt, or just a willingness to be surprised I think is a great virtue. And it’s a great virtue when we approach other people, strangers. It’s not really the way we get trained.

We kind of get trained and educated to arm ourselves with who we are and with representing that. And there’s a place for that. But to walk through the world open to being surprised, and open to being surprised by people who are very different from us, opens all this possibility and it’s also more pleasurable than walking through the world armed and ready to judge, and thinking you know everything. That’s a heavy burden to bear. Knowing everything. [laughs]

[music: “DBS” by Pilote]

MR. IYER: I’m Pico Iyer and this is On Being. Today I’ve decided to turn the tables on Krista Tippett. I interviewed her at the University of California Santa Barbara as part of this season’s Arts & Lecture series.

MR. IYER: You have this wonderful quote, I think Sherwin Nuland might have shared it with you from Philo of Alexandria. “Be kind because everybody is fighting a huge battle.” Something like that. That seems to be animating a lot of your conversations.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.” I have that on my wall in my office. It’s something that you can write down in your journal. It’s something that you can take a breath and say to yourself, even when you are with — in the midst of one of life’s many encounters with someone unpleasant. But to remind yourself that they are fighting some kind of battle that you can’t see and can’t know. And we know that’s true. It’s true. We say it and we know it’s true of ourselves. We know it’s true of everyone we know well. And it creates a bridge or it softens.

MR. IYER: Yeah. Now — and, in fact, you were saying on our way over here — that there are old truths, but there are also old truths that we’ve forgotten. And that’s one of them, because it sounds so self-evident, but we go through life pushing everyone aside as if we never knew it. And it seems like this book, maybe even more than any of the others, is about taking your ideas and putting them into practice, bringing them to the streets. Would you say you’re ever more interested in that?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And people have been asking me these last few days, like, how do I define wisdom because even though I wrote a book with the word “wise” in the title, I don’t ever say, this is wisdom. But there are many breeding grounds of wisdom. There are many qualities that it has. But I think think one core aspect of wisdom, when you experience it in another human being, is that there is an integrity, a connection between inner life and outer presence in the world. Knowledge is something you can possess, intelligence is something you — we can point at someone and say that’s an intelligent person. And wisdom is also — it’s a possession, but it’s a possession that is applied, right?

So the litmus test of wisdom is not just what is contained in that person, but their imprint on the world. Yeah, I think it’s true that all these years of this cumulative conversation to me that, I mean, the point of learning to speak together differently is learning to live together differently. And I’m not that interested in faith, or spiritual life, that doesn’t have a practice about it, right? That’s not put into practice.

MR. IYER: Yes. I think you quote the great, old physicist Freeman Dyson. He’s always had this line I love, which is, “I’m not a believing Christian, but I’m a practicing Christian.” That’s the heart of it, isn’t it?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. [laughs]

MR. IYER: And then, I think Stephen Batchelor, again, the questioning Buddhist, says something about “Buddhism is not what you believe, it’s what you do.” And I think those a simple formulations, but they open up this whole universe.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And I also think that that assertion is an antidote to what went wrong with religion, with public religion, in this country and perhaps in other places. But religion as a matter of positions and issues and arguments. I mean, to me that whole phenomenon was about religious voices squeezing themselves into political boxes, and political modes of discourse in order to be heard. But in the process, distorting, you know, the message that they were sending. Beyond distorting what the essential truth of what they were supposed to be representing beyond recognition.

MR. IYER: In fact, taking the deepest part of us and making it the shallowest sometimes. And I’m guessing it was witnessing all that that moved you to embark on the show, and feel that as you’ve written often there’s this vast group of us in this country, almost the silent majority, who care about these issues, but we don’t want to be fundamentalists, we don’t want to be new atheists. We want these questions to be alive. And is that part of the animation behind your hope starting the program?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And I have just become more and more acutely aware of how in American culture we hand over our imagination and our deliberation about everything. We set up these competing poles, and religious voices have played into that same dynamic, as well. Any important issue that we have to take up, we create the sides. But we know that in life it rarely works that way. Either in ourselves or in anyone we know.

So we hand over our deliberation to these — to almost a caricature of the deliberation. And we have to take it back, right? I don’t know if there’s such a thing as the “center.” I’m not sure I believe that there’s a center. And I also think most of us have lots of contradiction in our own — even if we have a position. But on any important subject, left of center, right of center, I think all the way up to those extreme poles that we let frame the discussion, there are people who have some questions left alongside their answers. And that is the reality, and I think that we need to claim the power of that vast middle and heart of our life together.

MR. IYER: Yeah. I mean, that’s the open space, and that’s what change can happen, I think. And I think, again, of a line with everything you’ve been saying, I feel that with your guests you often talk about doubt, or suffering, or imperfection. Because imperfection is the definition of humanity, really. And it’s our times of crisis when we really have to wonder what is going to carry us up. Would you say that that’s often something that you’re intrigued by, because it leads to …

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. There is this great puzzle about life that things go wrong, right? Perfection can be a goal, but it’s never a destination. And this has given rise across history to the whole theodicy debate. If there — how could there be a good God, or how could the universe, the balance of the universe be good when there’s so much suffering? And so that question is there and it’s real, and reasonable.

But then there is also this paradox that we are so often made by what would break us. And I think this is where our spiritual traditions, where spiritual life is so redemptive and necessary, because this is the place in life that says — that honors the fact that there’s darkness — but also says “And you can find meaning right there,” right? Not — it’s not overcoming it. It’s not beyond it. It’s not in spite of it. What goes wrong doesn’t have to define us but, I mean, again, to come back to what wisdom is, as I’ve seen it, it’s people who walk through whatever darkness, whatever hardship, whatever imperfection and unexpected catastrophes or the like, the huge and the ordinary losses of any life, who walk through those and integrate them into wholeness on the other side. That you’re whole and healed, not fixed. Not in spite of those things, but because of how you have let them be part of you.

[music: “We Move Lightly” by Dustin O’Halloran]

MR. IYER: You can listen again and share this conversation through onbeing.org. I’m Pico Iyer. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “We Move Lightly” by Dustin O’Halloran]

MR. IYER: This is On Being and I’m not Krista Tippett. I’m Pico Iyer. I’m a writer and long-time fan of the show, as well as a one-time guest. And today I’m performing a kind of “theft of the dial” whereby I ask the questions to host Krista Tippett about her New York Times bestseller Becoming Wise. We spoke recently before an audience at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

MR. IYER: You have this beautiful line in your book. “We learn to walk by falling down.” And it’s a perfect reminder that we can’t do anything unless we’re willing to fall. Really, one of the most moving moments, I can remember in my life was I went with the Dalai Lama up to a fishing village that had been completely devastated by the tsunami. 19,000 people died there. The whole place was in ruins. And when he got there, hundreds of people were lined up along the road, just so touched that he’d come to seek them out. And when he got out of the car, he went and blessed them, and he held them, and he gave them lots of inspiring words.

“Look to the future, that’s how you can honor the people you’ve lost. And build up your community as your country built up itself after World War II.” And all the kind of things you would hope a man of wisdom would say. And then when he turned around, I saw there were tears in his eyes. And I thought, that’s what wisdom really is, the ability to pass on exactly the right kind of truth, but to feel the suffering and the helplessness before it. And to be a human in the midst of being a wise man.

And I think one of the bravest things that you do in your writing is, I’m guessing you’re a fairly shy person despite your position in the public. And you write about the difficulties in your own life. I think in your first book, you mention that you suffered through periods of clinical depression, and your divorce from the father of your children. And in this new book, you talk a little bit about your separation from your father. And clearly that’s something that’s still with you every day.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. That was a hard thing about writing the book.

MR. IYER: Of course.

MS. TIPPETT: And I — it came late. First of all, just that I had to get out of the mode of being the person who asked the questions and who’s drawing other people out. But then, the book, it just — it didn’t come alive for a long time, and I realized, actually, I also had to do what I ask other people to do, which I know makes ideas come to life, and also makes them listenable, makes them land in the imaginations of listener with vitality, which is to really walk that line, that intersection between what you know, and who you are. And, yeah, then I had to actually — I had to be honest, even just with myself, about the hard, the sad parts of my life, and those things that I wrestle with.

So there’s the middle chapter of the book, which is really important to me, is the chapter on love. I really believe that in this 21st century where our lives, our well-being, our survival, our flourishing, is linked to the well-being of others in a way — and others on the other side of the planet, as well as the other side of the city, in a way that’s unprecedented in human history. That love as something practical and robust, and muscular, not romantic, love in all its fullness is maybe the only calling high enough for us to rise to this occasion. But love is also absolutely the hardest thing. So, to be honest about what that challenge is collectively, I had to really be honest about what that challenge is close to home. And, yeah, I mean, my life of love is, there’s a lot of beauty in it, and there’s been a lot of failure in it. And I think that’s a — I think that’s true for everybody with infinite variety.

MR. IYER: I think an especially difficult thing for somebody who’s sort of in the limelight and who’s regarded by many people as a spiritual guide…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, that’s right. [laughs]

MR. IYER: …to render herself so vulnerable, but I think that’s the power of it, because it reinforces you’re not somebody with all the answers. You have questions. When I listen to you on the show, and when I was talking to you on your show, your questions sound completely genuine. You are really trying to find out. To engage with a person, walk into the mystery with that person. And it’s wonderful that you have none of the answers in advance or not all the answers in your life, because that is what gives the life to it.

And I notice, I think one of your most recent shows broadcast was with the poet David Whyte. And one of the lovely qualities you bring into many discussions is motherhood. And I think you said your second child is about to go off to college and, suddenly, six months from now, it’s going to be an empty house.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s going to be a whole new world. Right. I am all about deromanticizing virtues and so the bad news is that if we tell the truth about love, it’s a hard truth. It’s just love crosses the chasms between us, and it brings them into relief. Like nothing else. But, the good news is, when we think about something lofty like love, if imagining that as a public virtue, which, by the way, all the great social reformers have done, right? That was Martin Luther King’s dream, the beloved community. That’s the unfinished business now. The changes in laws and policies float out of that.

But we do get to take seriously our concrete experiences with this things, right? So if I’m reflecting on love as a lens for us to reimagine our economic and racial disparities, or even to put that in different language, our belonging to each other and if our starting point, if our vision is our belonging to one another, what different strategies and visions flow out of that different starting point?

But then — so to be practical, to go into that in a realistic and powerful way, is to really analyze, like, what do I know about love in my ordinary life? And in fact, I know a lot. And a lot of what I know is challenging, but knowledge is a form of power.

MR. IYER: Mm-hmm. I think you’re right. “In the end, we’ll be measured not by what we’ve accomplished, but by how we love.” Is that right?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. IYER: And you refer to motherhood as “fierce love,” which I really love.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. The fiercest. Yes. [laughs]

MR. IYER: And it’s so interesting to me that, I mean, even as you’re looking at the hard stuff of the heart and the spirit and the world, the atmosphere of your show is really positive. I feel it’s always looking forwards and tilted towards hope. And you write a lot about hope in this new book.

But one of the things I love, for example, is that you have one of your guests talking about Hurricane Katrina, and all of us associate that with dispossession and the fractures in our society. He points out it was the greatest event of civil giving in the history of the United States. In order words, just to speak to what you’ve been saying, people reached out to the other more than at any other time in history. And I think again and again, even in the face of public disaster, you’re highlighting these points of hope, that of course, the regular media tends to jump over, or put on page A14 a bit.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s right. In a little sidebar. Journalism, as it’s come down to us from the 20th century, is incredibly sophisticated at analyzing the crisis, the catastrophe, the corruption, the failure. And those realities are there, and need to be reckoned with. But they aren’t the whole story. They’re never the whole story.

MR. IYER: Yeah. And it’s actually often in a crisis that people most forget themselves in the best way, and suddenly, without even thinking about it, scoop somebody off the railway track, or whatever.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. When the worst happens in the world, there’s always a part of that story where people rise to the occasion. I think about this so much. Dorothy Day, saint — none of the actual people who have been sainted were cartoon cutout characters with perfect lives. I mean, they had rough edges, and they knew the darkness in the world, and in themselves. So Dorothy Day had this really messy life. A beautiful life.

And I see a defining moment for her, again, coming back to this spiritual origin of questions, where she’s an eight-year-old girl in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, living in Oakland, and watches people just emerging from that devastation. And watches also all the adults around her start caring for strangers in a way she’s never seen before. And with the clear-sightedness of a child she sees that somehow they knew how to do this all along. And she asks this question, “Why can’t we live this way all the time?”

And I think that her life was one long — she walked into that question. And the catholic worker was part of her answer to that question. I love that question. I think we could ask that kind of question. That could be like just a spiritual discipline in very ordinary moments, in very ordinary weeks when — and this happens to us all the time. And we kind of don’t honor it in a way by not taking it seriously. Kindnesses, little moments of kindness from a stranger that make your day. You’re having a bad day and suddenly you’re not anymore. And just letting that question “Why can’t we live this way all the time?” — when we show the best of ourselves, letting that animate us.

MR. IYER: Yeah. Well, then I think that’s a variation on the age-old universal spiritual principle of having a skull on your desk. In other words, realizing time is limited. We may have six months, we may — we don’t know. But if you are given such a sense and so bear that in mind as monks in every tradition do, then instantly you think tomorrow, if I only have a few days left, what am I going to do? Extend myself entirely to somebody else. Give myself only to what sustains me. Think about what’s important. And one thing that you stress, and again, I think one of the things I most appreciate about your show, it’s very rigorous, and it points — in the book you say words like tolerance or diversity, even love, have slightly lost their meanings. We throw them around all the time. They’re attenuated. But you stress that hope is not the same as optimism.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

MR. IYER: And optimism can lead us into the clouds.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. I never use the word “optimism.” And I know — I have met people who use “optimism” the way I use the word “hope,” but for me, “optimism” sounds like kind of wishful thinking. “We’ll hope for the best.” “We’ll see the sunny side.” And for me, hope as a force, as a resource, is reality-based. It sees the darkness. It takes that seriously. It sees the possibility for good and redemption. And takes that seriously. And it’s a choice.

And it’s also — it’s an action. It’s something you put into practice, and I do love this convergence of our need for virtues in the world, of our need for tools to pin aspiration to action, and also what we’re learning through neuroscience about how what you practice you become. And that goes for being more patient, being more hopeful, being more compassionate just like it goes for any other skill.

And so I think you can be — you can choose to be hopeful, which is a more courageous — far more courageous choice than cynicism. I mean, cynicism is really easy. It’s never surprised or disappointed. And doesn’t lift a finger to change anything. And but hope can be — we can develop spiritual muscle memory. The more we do it the more we — and it’s really not about feeling it. Doesn’t have to be about feeling it in the first instance. But it can become instinctive.

MR. IYER: Yes. I think you say it’s a choice that can become a habit that becomes spiritual muscle memory. That’s exactly the Dorothy Day phenomenon. And in my limited experience, Desmond Tutu, or Martin Luther King, or Dalai Lama, all saying that. Desmond Tutu begins one of his books, and his says, “I’m not an optimist. I’m not an idealist. I’m a realist.” And that you have to begin with …

MS. TIPPETT: I love that, yeah.

MR. IYER: We have to change it.

[music: “Lullaby (Instrumental)” by Wes Swing]

MR. IYER: I’m Pico Iyer and this is On Being. Today I’m asking questions of the usual host of the show, a friend from afar, Krista Tippett. I interviewed her at the University of California Santa Barbara as part of this season’s Arts & Lecture series.

MR. IYER: Well, I’ve got to ask you, as you talk about hope and spirit and intimacy, and all these — the most precious stuff of life that’s not always in the public domain, do you have other pressures put upon you about whom you choose as guests or what kind of things you say? Do people ever say to you, “Well, this is not going to reach 10 million people. This is too subtle or thoughtful,” or something.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, there was a lot of that in the early years. Even just doing an hour-long conversation with the same person, even on public radio, we tell ourselves all these stories about how we have such limited attention spans, and how we have an appetite for entertainment, and I think that there’s truth to that. We have been trained to be entertained and to need things to be efficient. But, I also think that this profusion of, I mean, all the things that come at us in some ways reawakens our need to carve out at least some little space where we can go deep and be quiet. And be reflective.

There’s language in media about — people would say, “Well if you’re having these serious — these big conversations, it would have to be destination listening.” This was in like the early 2000s. And they basically said there’s — people don’t do destination listening. They do destination TV, but they don’t do destination radio. And that was kind of true, but the miracle in the meantime is podcasting. Which creates the opportunity for destination listening. And we have so many millennials in our space. They have audio habits and they have these portable devices, and so they can actually carve out that space and decide, and they can even multitask. I mean, you can run and listen to the [laughs] to the long form in-depth conversation.

MR. IYER: Yeah. And I often think of your show as having more poetry than anything in it. Not just because you feature poets, but more because poetry slows us down, and your show, it stretches our attention span. And poetry is really about romancing the mystery. And makes one think that anything that diminishes mystery is a kind of blasphemy. It takes us into that imaginative space you’ve been describing, where we don’t know what’s going on. We’re searching. And that’s the excitement of it.

But I also think you’re sort of redefining intimacy. You have actually a lot of wisdom in your book that all of us can use about exactly what avenues will shut out conversation just in daily life, and which will open them up. And you said that if the certain things that will put somebody on the defensive and that’s the end of the interaction. And others that will open them up, and then you just go deeper and deeper.

So, in some ways, I mean, I’ve learned to be a human being by listening to your program and thinking about what are the ways when I meet somebody tomorrow I can try to draw that person out rather than to create the divisions between them. And I was thinking over these last few days and months, whether you feel there are other places that you can turn in the media for similar kind of substance? I thought well, apart from your reading of books and …

MS. TIPPETT: These days, I don’t take in media the way I used to. Which may be true of a lot of us. What I don’t have any appetite for — I just have so little appetite for just kind of straightforward news coverage anymore. Because it’s demoralizing, it’s not the whole story. And so I love science news that is actually telling us what we’re — a story of what we’re learning about ourselves. And it’s often so strange, and unexpected. That’s where you have this real surprise, and there’s a lot of beauty in it. And even if it’s hard news, it’s told in a complex way.

I love a lot of the journalism around food now. And there’s some great BBC — and there’s a BBC — they have the most boring titles. The fact that everyone hears it means that they don’t have to work at all to make it cool. So it’s like, The Food Programme. [laughter] But it’s this brilliant program about — and it’s really not about food, it’s about how — and in the book, I ended up writing a lot about food and us as creatures who eat. And food is about sustenance, and food is one of these — a perfect example of this — that wisdom can be something you accumulate. It can be new insights, new discoveries, but sometimes wisdom comes in the form of relearning something that we knew forever and then forgot.

And in the area of the entire subject of how we eat and how we grow, and raise what we eat, which has all these economic implications, it’s also — that is also a reminder that progress — that innovation is not always progress. And so we walked down this long road to completely distorting not just our agriculture, but our own bodies. And so now we are just painfully pulling that back, rediscovering local food. Rediscovering local food? Rediscovering real food. It’s incredible. [laughter]

So, I don’t know, so I guess this is the kind of news I like, because this actually is telling the story of our time. As much as those stories of crisis. So, that’s kind of what I take in.

MR. IYER: Yeah. And one of the inherent challenges of your job must be that often there’s people who know the most and have the most to impart are the most private. And that the quiet voices are the ones that you actually have to go and find, because they’re not the ones we’re hearing on the media. And the people who know most about faith say least about it. Is that your experience?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. It’s a real irony that the people who are changing the world in good ways often have a quality of humility about them. They don’t have publicists. They haven’t branded themselves. There are people who are changing the world in good ways who are also good at branding.

But there are a lot of, I would say the — there’s this notion of the change that happens in the margins, which is where real social change, the human change that makes social change possible, has always begun. And it begins out of sight, and that this, I think — I think of this as a spiritual discipline, especially in a world where we have so much information. This spiritual discipline of going out and looking for those redemptive parts of our common story that precisely because they are so beautiful, and true, and humble, are not going to jump up and down and say, “Hey, pay attention to me.” Listening for those voices that will not shout. And it’s precisely the goodness that they bring is precisely in that fact, and it’s also why we have to listen for them. They will not throw themselves in front of microphones.

MR. IYER: Yeah. And when I think one of the exhilarating things in this new book is there are a lot of very young voices. There are more women, I think, than ever before. There’s some great diversity of backgrounds in it. Just my last question would be, what is hardest for you in your life or in your work?

MS. TIPPETT: What is hardest for me?

MR. IYER: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm. Sometimes — I think people sometimes imagine that because I soak up all this wisdom, I must be really special. [laughter] Extra-wise, myself. [laughs] And, in fact, I have a life like everyone else. And I think parenting is just this unfolding experience of humility. [laughs] You learn all the time what you don’t know, or what you might have done better. And my life is no different.

A lot of weeks my moments of great accomplishment is when I manage to get the recycling out on the right day, right? I mean, so, maybe I would say at this point in my life, it is precisely that. Wanting to hold myself but more to letting myself take in, even — I ended up stressing, in the book, and like I had to keep reminding myself to stress that talking about wisdom and virtue, that these are pleasurable things. Right? That life is better, that your step is lighter. That pleasure and delight itself is a virtue.

And I’m kind of intense, right? I’ve been kind of intense in my life. And I talk in the book I mean my childhood was — made me that way, too. And it’s been — it’s also been a gift. But I’ve often — I talk to young people a lot, people in their 20s, and I say, “If there’s one thing I wish someone would have said to me that I could have taken in is: yes, you will be beset by doubts, right? You will be second-guessing yourself. And you’ll think you’re supposed to have things figured out. But whatever is going on, know to take pleasure. Whatever there is to take pleasure in, do that.”

And I think I’m talking to myself still when I’m saying that. And I actually think one of the great things about getting older, about being in my 50s, they say that when we’re younger our brains are tuned to novelty, to be animated by novelty. But as you get older, you’re less tuned to novelty and I would say more naturally attuned to kind of take pleasure in what is ordinary and habitual. And I think that’s a great gift. So I am trying to really live into that. And also just, I mean, it’s so ironic because I have all these conversations about health, and wholeness, and trauma, and healing, and, I mean, just being rested and restored. So my struggles are pretty basic. [laughter]

MR. IYER: I can tell by the way what a good listener you are, because usually when I’m sitting in this chair, I say almost nothing, and you’ve got me babbling and babbling through this evening [laughter] with your attentiveness. Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a conversation, it’s not an interview.

MR. IYER: It is. And I just want to end by saying you had a really profound program with the poet Christian Wiman. And he said that every now and then he starts wondering if there’s a future for poetry, or is he going to be able to support his family, or what’s going to happen next month. He’s living with uncertainty. And then he has a really honest and intimate conversation with a friend, and he says beautifully, it clears the air and it returns him to the best part of himself. So, I just want to thank you on behalf of all of us for clearing the air tonight and clearing the air for millions of us for many, many years, and bringing us back to that part that’s most cherished, and most easily lost. So thank you so much.

MS. TIPPETT: Thank you.

[applause]

MR. IYER: Krista Tippett’s books include Speaking of Faith: Why Religion Matters and How to Talk About It, and Einstein’s God: Conversations About Science and the Human Spirit. Her latest book is Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living.

[music: “Night In the Draw” by Balmorhea]

MS. TIPPETT: OK, now I’m taking the microphone back. Thank you, Pico Iyer. I love his books The Art of Stillness and his fantastic work of reportage and memoir, The Open Road, about his three decades of conversation and travel with the 14th Dalai Lama. And my interview with Pico remains one of our most popular podcasts ever. Find that, or listen to this show again, and discover all the shows we’ve ever produced, at onbeing.org.

Over the years some of you have asked us to produce shorter, better sharable content. And we have heard you. We’ve just launched the new Becoming Wise podcast, vignettes on the mystery and art of living, drawing on stunning moments with voices like Brené Brown, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, John O’Donohue, and Elizabeth Alexander. Find these and all Becoming Wise episodes by subscribing on iTunes, Stitcher, or Soundcloud. There’s a new edition every Monday.

[music: “Quiet Mind” by GoGo Penguin]

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Annie Parsons, Marie Sambilay, Tess Montgomery, Aseel Zahran, Bethanie Kloecker, and Selena Carlson.

Special thanks this week to Roman Baratiak, Eric Moore, Miguel Decoste and Daniel Muldonado.

Our major funding partners are:

The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the frontlines of social change worldwide at fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build a spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, contributing to organizations that weave reverence, reciprocity, and resilience into the fabric of modern life.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

And the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.