Lawrence Krauss

Our Origins and the Weight of Space

One of the values of science is to make us uncomfortable says Lawrence Krauss. The particle physicist explains why we should all care about dark energy and the Higgs Boson particle. Science literacy matters, and, more importantly, he suggests we should take joy in science — just as we cultivate enjoyment of arts we may not completely comprehend.

Image by Pascal Boegli/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Lawrence Krauss Lawrence Krauss is Foundation Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and Physics Department, and Inaugural Director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University. His books include The Physics of Star Trek and A Universe from Nothing.

Transcript

April 11, 2013

Krista Tippett: The physicist Lawrence Krauss says that one of the values of science is to make us uncomfortable.

Lawrence Krauss: I don’t mean that science isn’t spiritually uplifting. I do think it is, but for the very antithetical reasons to religion, I guess, is the fact that it causes us to feel less comfortable should provoke us to try and understand what we can do and what meaning we can make in the universe. So learning that the universe isn’t made for us, or there’s no evidence that it is, is profoundly inspiring or should be.

Ms. Tippett: Lawrence Krauss helps explain why we should all care about dark energy — and, for that matter, the Higgs boson particle. He believes that science literacy matters, but more importantly that we can, should take joy in science — just as we cultivate enjoyment of arts we may not completely comprehend.

I’m Krista Tippett. This is On Being, from APM, American Public Media.

I invited Lawrence Krauss’s passion for science as our common human inheritance to the Chautauqua Institution in New York. We sat together in the outdoor Hall of Philosophy during the 2012 summer season. The theme for the week was inspiration, action, and commitment.

Ms. Tippett: Public theology has a long history at Chautauqua. And, in earlier generations, that meant a voice like Reinhold Niebuhr, an authoritative Christian voice in an overwhelmingly Christian culture. Today’s guest takes us in a completely different direction, but one which I find equally distinctive and influential in our time. Lawrence Krauss is a cosmologist, a theoretical physicist, and a public scientist bringing the learnings of science to the rest of us, to the wider world. So the science-religion debate is well known, and Lawrence Krauss has strong views on that. But in my mind — I’m just going to lay my cards on the table.

What science might have to say about God or what religion might have to say about science is not really what either of those disciplines are for. I am, however, fascinated by how scientists in our time — neuroscientists, biologists, and certainly physicists and cosmologists — are adding their own insights and questions to realms of human inquiry that religion and philosophy long dominated. Where did we come from? What does it mean to be human? What does the future hold? What is our place in the universe? Science is as much at the center of everyday life as it’s ever been. I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that some kind of science and technology is woven throughout every moment of every day for many of us.

Lawrence Krauss is foundation professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the physics departments at Arizona State University. He’s the associate director of the Beyond Center there and director of the Origins Initiative. His books include The Physics of Star Trek — and we will talk about that, don’t worry — Fear of Physics: A Guide to the Perplexed and, in 2012, A Universe from Nothing: Why There is Something Rather Than Nothing. As we start, tell us about the origins of your life as a scientist.

Dr. Krauss: My mother wanted me to be a doctor and my brother to be a lawyer. And, unfortunately, my brother became a lawyer and then, therefore, the pressure was on me to even more become a doctor. And my mother, unfortunately, since neither of my parents went to — even finished high school actually, I think helped get me interested in science in the sense that she mistakenly told me that, you know, doctors were scientists.

Ms. Tippett: Well, medicine is somewhat related.

Dr. Krauss: Some of medicine is, certainly. Most doctors are not scientists in the sense that …

Ms. Tippett: Right, right.

Dr. Krauss: Therefore, but I got interested in science and I started reading about it a lot when I was a kid. So reading about science, particularly about scientists and books by scientists in particular, had a big impact on me, and I guess it was sometime in high school when I realized that doctors weren’t scientists and I was kind of hooked on science. Also, I had crummy biology teachers. And physics was always by far the sexiest of the disciplines and still is, by the way.

In fact, that’s one of the reasons why I guess I write is to return the favor because I was turned on by books by Isaac Asimov and George Gamow and people like that. I actually wasn’t convinced I was going to do physics. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I did history for a while because physics seemed detached from people and I’m very political as well, as we may get to. Because in fact to amplify what you said, science is not just a part of everyday lives. It’s a part of every important political decision that has to be made, yet it’s never discussed by politicians, one of the things I’ve been working hard to change. I mean, a very long answer to a short question, but …

Ms. Tippett: No, no, that’s OK.

Dr. Krauss: But the reason people do science is not to save the world. It’s because it’s fun. That’s the only reason that people do science. Generally, you’re not going to work for 20 years on a given subject unless you enjoy it, and I think that we don’t explain that enough.

Ms. Tippett: You have said that physics is a human, creative, intellectual activity like art and music. I mean, you talked a minute ago about the fun. I mean, you use the word pleasure. Talk some more about that.

Dr. Krauss: Well, yeah, no, I think it’s very important. I just wrote about this. I think people somehow view science in terms — in a utilitarian way as if the value of science is the technology it produces, but I think that’s completely mistaken. I think, obviously, science is responsible for the technology that’s allowing us to have this discussion and pretty well everything that allows most of you to still be alive, which is vitally important and, therefore, it’s changed our lives more than anything else.

But to me, the most exciting thing about science is the ideas. Science has produced the most interesting ideas that humans have ever come up with, certainly among the most interesting. And somehow, although it wasn’t always this way — you know, I was just having the discussion in Aspen last week on this very subject. It wasn’t always this way, but now somehow the ideas of science are not a part of our culture.

It’s perfectly acceptable to consider yourself literate if you know something about Shakespeare, but not if you know anything about the Higgs boson. And I think that’s a mistake. As I say, it’s relatively recent. You used to be considered illiterate if you didn’t have some ability to discuss at some level natural philosophy 200 years ago or even at the turn of the last century. And now it’s perfectly acceptable to say, oh, you know, I don’t get science, and scientists are responsible for a lot of that, I have to say. But it’s the ideas of science that make it so important for humans because it’s part of what makes being human worth being human.

As I often say, we don’t remember the Greek plumbing. We remember their architecture and their ideas. Most people don’t have to know how to build the detailed things of science, but the ideas change our perspective of our place in the cosmos. And to me, that’s what great art, music, and literature is all about — is when you see a play or see a painting or hear a wonderful piece of music. In some sense, it changes your perspective of yourself. And that’s what science does in a profoundly important way and a way with content that matters.

Ms. Tippett: You’re a musical person, or you love music. You’re passionate about music, aren’t you?

Dr. Krauss: On paper, I look like a musical person.

Ms. Tippett: OK.

Dr. Krauss: I do like music. I like art, but, yeah, I like music a lot. I mean, if you’ve read my biography, you know I have some apparent credentials, but they’re all fake.

[Laughter]

Ms. Tippett: Glad we clarified that.

Dr. Krauss: I was nominated for a Grammy, I will admit that. I just have no musical ability, but my daughter was very musical and played the violin in Cleveland, in fact. So I’ve learned a lot through her.

Ms. Tippett: So I think I probably first became aware of you with The Physics of Star Trekbecause I was a huge — well, still am a huge Star Trek fan. And can I just say I’m so pleased that you’re talking about all the generations, you know, Commander Data.

Dr. Krauss: Absolutely. It’s important.

Ms. Tippett: The voyagers, as well as next generation.

Dr. Krauss: That dates both of us, by the way, but in any case…

[Laughter]

Ms. Tippett: OK. You know, I think as I’ve spoken to lots of scientists over the years and I think sometimes it’s surprising to non-scientists that scientists love science fiction. I mean, you wrote somewhere that all physicists you know watched Star Trek growing up. But then as I was thinking about this and thinking about the way you put science like in the realm of being cultured and arts. I mean, science fiction is a narrative, imaginative rendering of what scientists do and discover.

Dr. Krauss: It’s interesting you should put it that way, in fact, because people imagine science fiction as an imaginative rendering of science when in fact science is a far more imaginative rendering of science fiction.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: No, somehow that’s the point. Creativity is not something — and imagination are not things that are only associated with science except Richard Feynman, who I did write a book about, said, you know, science is imagination in a straitjacket. And it’s far more difficult to conform your imagination to the evidence of reality than to invent your own realities. In fact, religion is an example. I’ll wait for the response.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. We’ll get to it, but I’m just not going to go there yet, OK?

Dr. Krauss: But anyway, no. So I did like science fiction until I discovered that science is much more interesting than science fiction. The universe continues to surprise us in ways that we would never imagine, which is why — by the way — why I’m a theoretical physicist.

But science and physics are empirical disciplines. And if we just thought about the universe — and, again, to not be completely facetious, philosophy was an example of that — if we just thought about the universe, we’d come up with the wrong answers because the universe is far more imaginative. So we have to keep probing the universe and asking questions — and that means doing experiments and observations — because it constantly surprises us in ways that no one would have imagined. One of the things that amuses me about science fiction is how it misses all the really big things.

Ms. Tippett: So do other physicists watch Star Trek growing up and then they realize that science is more interesting?

Dr. Krauss: It’s hard to know. I mean, I’ve thought about that a lot. People ask me. It’s hard to know if watching Star Trek influenced them to become scientists or the other way around or whether their interest in science was promoted. I think there’s no doubt, and Stephen Hawking wrote the foreword for that particular book and he said, you know, it helped spur the imagination and it does.

So to the extent that I think it was one of the — I used to think it was a geeky thing to watch Star Trek. It isn’t. One of the things that amazed me when I wrote that particular book, that shocked me, was how broadly and deeply Star Trek had permeated not just the culture in the United States, but around the world. And it wasn’t just 16-year-old boys watching it.

Ms. Tippett: No.

Dr. Krauss: And people who became scientists, lawyers — and women. It’s kind of interesting. It’s not a gender thing either. The reason that I think that’s the case is that it presented two things: a hopeful view of the future, which science fiction doesn’t often do, and a view of the future where science actually made the world a better place. The Star Trek future is a better place because of science and, I can’t resist saying it here now that I think about it, but it was one of the reasons, if you know in Star Trek, that basically they dispensed with the quaint notions of myopic views of the 20th century, including most of the world’s religions.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, OK. We’re not going to go there still.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: OK. I keep trying to get you there, but it’s not going to work.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, they did, but then you had in the next generation this kind of immortal, semi-divine …

Dr. Krauss: More of a Q.

Ms. Tippett: Q. We probably shouldn’t do this. It’s too inside baseball.

Dr. Krauss: One of my favorite characters.

Ms. Tippett: I wish we could talk about this for an hour. And as you’ve pointed out often, you know, like literature and the arts, science is getting at origins. Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? So, but in a very different way than religion approaches these things or philosophy or the arts. So as a cosmologist …

Dr. Krauss: I’m biting my tongue.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. No, but I just want to hear from you like as a physicist, how do you approach the question of origins? What are you looking at? What are you exploring?

Dr. Krauss: Well, I think I’m exploring the same questions that people have had since people have been people. We all want to know where we come from, how the universe originated, how it’ll end, what we’re made of. And that naturally does lead to questions of is there a purpose and are we here for a reason, I think.

Ms. Tippett: But those aren’t science questions.

Dr. Krauss: Those aren’t scientific questions. And, in fact, that’s what I was just going to get at. They’re not scientific questions. I’ve gotten in a lot of trouble from some philosophers recently because I use the word why. Why is there something rather than nothing? And, in fact, as I say very clearly in the book, why questions don’t mean anything. They’re content-free. Any of you who have children have been asked why, why, why? In the end, ultimately the only answer to that is because. And that is also content-free because why presumes purpose. Whenever we say, we really mean how, at least in science.

Ms. Tippett: In science, yeah.

Dr. Krauss: And it’s true and that has content. When we mean why in religion, we’re presuming the answer before we ask the question. We’re presuming there’s purpose. There must be a reason for our existence, otherwise why? And science doesn’t make presumption, and the remarkable thing is science finds the universe works pretty well without that presumption. So when we ask, as we used to ask, you know, we could ask the question why are there nine planets? And there are nine planets, by the way. Pluto is a planet.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: I don’t care what my friend Neil Tyson says. My daughter studied Pluto in grade four and did a project on Pluto and I don’t plan for her to go back. But when we ask that question, we don’t — when Kepler asked the question, say, why are there five planets, he might have meant there was some divine purpose. He would talk about the Platonic solids and all that. But now we’ve changed the meaning of that because we realize that not only are there not five planets, but there’s nothing special about nine planets. There are solar systems around most stars we see. We’ve discovered 2,000 planets already.

So the question we really mean is how are there nine planets? How did our solar system arise? Is it different than other solar systems? Is it natural to have an Earth-like planet? Could there be life elsewhere? Those are productive questions. So science changes the kind of questions we ask by changing the meaning of words because we learn things. We change the meaning because we understand the universe and we make progress. And I would argue that’s why science — it’s nothing wrong about changing the meaning. It’s because there’s progress in science unlike, you know, theology.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: I’m sorry. I keep trying to hope I’ll provoke some people here. But what I mean by that is one of the values of science is to make us uncomfortable. Somehow that’s supposed to be a bad thing for many people, being uncomfortable. Being uncomfortable is a good thing because it forces you to reassess your place in the cosmos. And being too comfortable means you’ve become complacent and you stop thinking. So being uncomfortable should be a spiritually uplifting experience.

I don’t mean that science isn’t spiritually uplifting. I do think it is, but for the very reasons — the very antithetical reasons to religion, I guess, is the fact that it causes us to feel less comfortable should provoke us to try and understand what we can do and what meaning we can make in the universe. So learning that we’re more insignificant or learning that the universe isn’t made for us, or there’s no evidence that it is, is profoundly inspiring or should be.

Ms. Tippett: But I really want you to tell me, as a cosmologist, when you think of origins, stars, right? Stars that died …

Dr. Krauss: The reason I created the Origins Project or helped create the Origins Project at Arizona State and the reason I moved there to lead it is all of the interesting questions that I can see in science and, to most part, in scholarship beyond science, have to do with origins. The questions at the forefront of every field are origins questions. They’re really the heart that you’re trying to get at. In the case of the universe, you know, how did the universe begin? You know, are we the only universe? What happened before the big bang?

All those origins questions. But we study everything from the origins of the universe to the origins of life. Origins of life questions are profoundly interesting from a philosophical, but more importantly, from a scientific perspective right now. The origins of consciousness — if you think of the frontiers of human investigation, they inevitably involve origins and we’ve been pushing those origins questions back. Origins questions 200 years ago, when Darwin asked them, would have been very different.

Remember, Darwin in Origin of Species said — I think it was in Origin of Species; it might have been The Descent of Man — said — he never talked about the origin of life, by the way, right? He talked about the origin of the diversity of species. He never talked about the origin of life itself, and once he just poo-pooed it. He said origins of life, you might as well talk about the origins of matter because …

Ms. Tippett: OK. So that’s what you’re talking about now.

Dr. Krauss: Exactly. And that’s what’s great. We’re pushing back those frontiers. The reason I became a particle physicist is because it’s the fundamental structure of the universe that ultimately sheds light on all the complexity that we see. The universe seems to be incredibly complex. And one of the beauties of science is at some level the diversity of life, the complexity of the phenomena we see, we can understand in terms of a few very basic principles and how remarkable that is. I mean, how amazing that is, and that we should celebrate that.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with physicist and public scientist Lawrence Krauss at the Chautauqua Institution in New York.

Ms. Tippett: So one thing you’re really great at is explaining, you know, taking concepts of physics. I thought we might do a little bit of that, but maybe we save that for, you know, we ask you …

Dr. Krauss: If there’s any burning question you have, I’m happy to answer it.

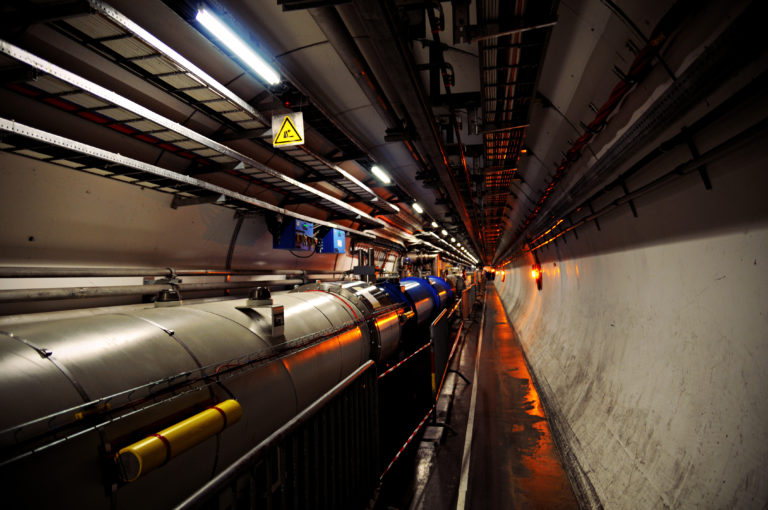

Ms. Tippett: I have lots of burning questions. But I think maybe what would be fun to talk about now specifically is the Higgs boson, which is something that’s out there that we’re talking about that’s not new, but newly, more likely, right? I mean, you can’t say 150 percent proven, but there’s new evidence, right?

Dr. Krauss: It certainly captured — yeah, not only captured the imagination of physicists from around the world …

Ms. Tippett: And that is one of these fundamental ways of talking about what it’s all made up and how it comes together. You know, how do you answer what is Higgs boson and why should I care?

Dr. Krauss: Well, the answer is not so pat as you often hear. People often say, well, it’s responsible for mass, but it’s not that. I was just doing an interview yesterday where someone said, well, I never asked why there was mass, so why should I care? And it’s true. It’s not as if you wake up and say, gee, why do particles have mass? It could be just a given. But there’s a much more interesting, intellectual reason why we’re led there and it’s a reason that we should celebrate. But I bet most of the people here don’t know why we should celebrate. So I’ll explain it.

Ms. Tippett: OK.

Dr. Krauss: We should celebrate revolution in our understanding that took place about 45 years ago or within the last 50 years, a totally complete revolution in our understanding of the universe that’s been unheralded. You don’t read about it much.

In the early 1960s, there were four forces in nature, electromagnetism, which you know of, and gravity, the two you’re mostly familiar with. There are two more, called the strong force and the weak force. In 1962 or ’63, we understand one, one force in nature. Electromagnetism was the only force we understood as a quantum theory. Quantum mechanics is the theory that governs matter on very small scales and forces. What is remarkable is, within a decade, we understood three of those four forces of nature.

I mean, it was one of the most amazing periods of scientific expansion in understanding the universe, and one of the most beautiful aspects of that is we understood that all of the forces in nature could be understood in terms of a single mathematical formulism. They had exactly the same structure mathematically, which is profoundly interesting, but even more interesting perhaps, you know you’ve made a breakthrough in science when two things that seem very, very different suddenly are recognized as being different aspects of the same thing.

The electromagnetic force is long-range. I can experience it across the room. The weak force operates only on the scale of nuclei. Those two very different forces could be understood as different aspects of the same thing. Now how can that be? Well, they could be same if at a fundamental scale all the particles are masses. They can be described by exactly the same mathematics.

And then what happens is, the mass of the particles that convey the weak force is an accident. It’s an accident of our existence if — and this was what seemed too good to be true — if this invisible field permeates all of space, you can’t see it, but if the particles that convey the weak force interact with that field and get slowed down like swimming through molasses, get retarded because of that interaction, they act like they’re massive. And it just seemed too good to be true. It seemed to be too good to be true for me.

Ms. Tippett: OK, so it’s like things appear to have mass the way they do because of the relationship they have to this field as opposed to something that’s intrinsically given.

Dr. Krauss: But we were driven to it not because the particles that make you and I have that mass, but because of this beautiful unification. That was what drove us to it. Then people say, hey, maybe if it’s true for these particles called the W and Z bosons, maybe it’s true for all the particles. Maybe all the particles can be mass less and the Higgs field …

Ms. Tippett: Including the atoms that make us?

Dr. Krauss: Well, including many of the particles that make us up, not all of them, it turns out. But the ones that are heavier act heavier because they interact more strongly with that field and the ones that are lighter are lighter because they attract less strongly and the ones that are mass less don’t interact at all.

Ms. Tippett: And light travels at the speed of light, so it doesn’t slow down and doesn’t get all …

Dr. Krauss: It doesn’t slow down because it doesn’t interact at all. Photons don’t interact. That was a proposed property. Now what’s amazing, as I said, seems kind of slimy, doesn’t it, to invent — well, I won’t make a comment about religion.

Ms. Tippett: No, good.

Dr. Krauss: But inventing invisible forces is not what science is all about. It’s what other things are all about.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: Science should be, if it’s there, we should be able to detect it. But the great thing is, so if it turns out it’s a consequence, that if there is this invisible field that’s doing all this marvelous stuff, then physics says if you hit it hard enough, if you smack that field hard enough with enough energy in a small enough region, you’ll produce real particles.

That’s a prediction and those real particles — the field is called a Higgs field — those real particles would be called Higgs particles. So if that field exists, you should be able to produce particles and see them, and that’s what we’ve been trying to do for the last 50 years.

Ms. Tippett: And that’s what happened in 2012?

Dr. Krauss: That’s what just happened, we think. We built the machine. We were building the machine in this country 25 years ago, well, 20 years ago, that would have been sure to detect these particles, we think.

But Congress, in its wisdom and then when it was much wiser was still pretty stupid, decided that even after building the biggest tunnel that had ever been built, 60 miles around in Texas underground, decided they couldn’t afford the $5 billion dollars to finish the project, which is now what the cost of air conditioning for a day during the Iraq War or something. But we decided we couldn’t built it, so it’s been built in Geneva. Fine, that’s life.

Ms. Tippett: So I want to understand this so badly. You know, I struggle to understand it. So when we talk about the Higgs boson that is an expression of the field, right?

Dr. Krauss: Well, in quantum physics, fields and particles are the same thing. All fields exist. The electric field, when you feel static electricity, classically that’s an electric field. Maxwell and Faraday described it beautifully. In fact, the first major unification was the unification of electricity and magnetism, two very different-seeming forces were understood by Maxwell and Faraday and others to be different manifestations of the same thing. Beautiful, just beautiful.

But that field that they called a field, we now understand is due to the exchange of particles, photons. And the weak force due to the exchange of W and Z bosons. And we understand that the Higgs field, the reason particles feel mass is by exchanging particles with that Higgs field, Higgs particles. And if they exist, as I say, we have to be able to detect them and we even predict many of their properties. That’s why it’s not just a crapshoot.

And the particle that’s been observed, the bump that’s been observed in Geneva, is Higgs-like. It seems to have all the properties of the Higgs, and it’s where we kind of would have expected it maybe to be, which is what surprised me because I was betting against it. I was sure this beautiful …

Ms. Tippett: Like Stephen Hawking betted against it too, right? He lost his 100 dollars.

Dr. Krauss: Yeah. Well, it’s one of the few times that Stephen and I agree, in fact. But it just seemed to good to be true and it’s so rare that nature obeys what we imagine to be true, that I thought nature would come up with a much more interesting way around it. In fact, what’s really beautiful is every time we make a discovery in science, we end up having more questions than answers. Having discovered the Higgs, if that’s what we’ve done, does not close the book because we still don’t understand why this Higgs field exists in the universe, which is really and why — and by why I mean how …

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: Why that Higgs field exists because that’s really what’s responsible for our existence. We wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for it. And we think that, besides just discovering it’s particle, there are other tantalizing hints, in fact, in the nature of what’s been discovered plus what we expect. It’ll say the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva will point us in the right direction to answering those questions.

We’ve been, as I often say, like people locked in a room with sensory deprivation for 40 years. What happens? You hallucinate, and that’s what most of the business of what I’ve been in is hallucinating for the last 40 years.

Most of the hallucinations we’ve had, namely theoretical physics, will be wrong. Most ideas are wrong. We don’t celebrate that enough, but it’s true. Most ideas are wrong, so all of the ideas may be wrong. But we won’t know until nature points us in the right direction. And I think, and many other people think, that if what we really discovered is the Higgs, there’s bound to be new things at the Large Hadron Collider that will point us in the much more interesting direction.

Ms. Tippett: And you don’t even know what that direction is right now.

Dr. Krauss: No, no. I mean, I have speculations. I have ideas and so do other theorists. I always hope I’m wrong. I’ve often said the two greatest states to be in if you’re a scientist is either wrong or confused, and I’m often both.

[Laughter]

Ms. Tippett: Yes, and in a positive way, you talk about that as beautiful and mystery is a word that’s absolutely part of your vocabulary.

Dr. Krauss: Mysteries are what it’s all about. In fact, not knowing is much more exciting than knowing, right? Because it means there’s much more to learn. The search is often much more exciting than the finding. Mysteries are what drive us as human beings. I think it’s really what drives scientists.

And the beautiful mysteries of the universe are what should keep propelling us because we are fortunate enough for whatever reason to have an intellect and have evolved —and I can still say that in the United States — to have evolved a consciousness that allows us to ask those questions and to stop asking them is just a tragedy.

Ms. Tippett: You can listen again and download this conversation with Lawrence Krauss through our podcast on iTunes or through our website, onbeing.org. If you’re new to podcasting, find out there how to subscribe. We’re also on Facebook at facebook.com/onbeing. On Twitter we’re @beingtweets. I’m @kristatippett. You’ll also find many more conversations with all kinds of scientists on our site. Again, that’s at onbeing.org.

Coming up, Lawrence Krauss on religion, love, and science as a social good.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, my conversation with physicist and public scientist Lawrence Krauss. His books include The Physics of Star Trekand A Universe from Nothing. I interviewed him before an audience of 1,000 at the outdoor Hall of Philosophy of the Chautauqua Institution. We’ve been talking about the nature and meaning of science in human life. We haven’t delved yet into the subject of religion — on which Lawrence Krauss also has famously impassioned views.

OK, so here is where I want to talk about religion.

Dr. Krauss: Oh, good. Good, because when we talk about stop asking those questions, it’s a natural segue to religion.

[Laughter]

Ms. Tippett: But actually, actually what I was going to say is I think a reverence for mystery is something that great scientists and mystics and, in fact, our traditions at their orthodox cores have in common. There’s the shared language of mystery.

Dr. Krauss: Yeah, I’ll give you that. No, I mean, the origin …

Ms. Tippett: Thank you.

Dr. Krauss: Yeah, except that science has changed the language because science has meaning. And I don’t mean that in a facetious way. I really don’t. I think that science and religion and mysticism all have their origins in the same — in being human. They all have common origins. The difference is that science has moved beyond, has taken us beyond our childhood.

Ms. Tippett: So one thing that happens to me because I spend my life in conversations, so I started to have this cumulative conversation in my head, and so a couple of people I was thinking of as I was reading you, a geneticist, Lindon Eaves, do you know him? He’s done a lot of the biggest long-term studies of twins, and he’s also an Anglican priest.

And he said to me that, when he was in his laboratory, religion most of the time had no place there. So, I keep it — I hold it at bay. At the same time, when he’s sitting at the bedside of somebody who’s dying of cancer, science has nothing to say in that moment. There’s meaning …

Dr. Krauss: Oh, I disagree about that. You know, I know all these people say — a very famous biologist said, “The minute I go in the lab, I’m an atheist.”

Ms. Tippett: What does science have to say to death, to dying, not to the biological breakdown of a body, but to the existential moment of dying?

Dr. Krauss: I think it has a tremendous amount to say. I mean, it has to say to us that, you know, first of all, it has to say what dying is. What is dying? What’s the process of dying?

Ms. Tippett: OK, there’s that, there’s that.

Dr. Krauss: No, no. I mean, we’re all going to experience it, and I think a realistic assessment of what the process is helps us understand what we’re going to experience and try and make sense of it. It seems to me you can’t make sense enough to make even an ethical or moral decision without understanding the basis in reality.

What seems to me what science could say is what I’ve sort of said in the book is that, look, what I’m about to say is going to sound awful, and I’m not going to go to someone’s bedside and offer this, OK? It’s up to them to decide if they want to look at these things. But we should at least offer the possibility of that knowledge that there’s no evidence — in fact every bit of evidence that there’s no afterlife, that you’re here, but in fact the meaning of your life is the meaning that you make.

And in your life, you’ve made incredible meaning. You created love for other people. You’ve brought up children. You’ve allowed people to have livelihoods and that meaning has made your life worthwhile and enjoy every second of being alive. And death is a sad but necessary part of being alive. That may not sound like the same comfort of saying that, you know, you’re going to have eternal life and you’re going to be with your family …

Ms. Tippett: I don’t think Lindon Eaves is talking to people about eternal life.

Dr. Krauss: No, but I don’t see why that’s any less comforting than …

Ms. Tippett: But what you just said isn’t science.

Dr. Krauss: Yes, it is. It’s saying there’s no evidence. I mean, here’s what we’re saying is that …

Ms. Tippett: But you can’t put meaning under a microscope. You can’t shoot particles at it in a Large Hadron Collider.

Dr. Krauss: No, but I don’t understand what meaning is till I ask the questions of how the universe behaves. And look, there could be — we can never disprove purpose, you know, so I can never say there’s no purpose to the universe. I could just say the universe behaves as if there’s no purpose, but that may just mean I’m missing the point, as a lot of people may think. But there could have been. You can answer it in the positive, but there’s no evidence.

If the stars tonight realign themselves and said I am here — in Greek, presumably [laughter] ancient Greek — then, hey, I’d say, you know, maybe there’s something to all this. But in the absence of that, if Bertrand Russell said, you know, I can’t disprove that there’s a teapot orbiting Jupiter, and I can’t. There’s no evidence of it and it’s highly unlikely. And I think providing that reality check is useful to people, not just when they’re dying, but when they’re alive, seems to me.

You know, some people say that religion gives meaning to their lives, but to me, the knowledge that the meaning we have is the meaning we make should inspire us to do better. So I think that — I personally think that every single thing that religion provides, rationality, empiricism and science can provide, and not only that, it can provide it better.

[Applause]

Dr. Krauss: Well, what do you know?

Ms. Tippett: So the other voice that was in my head was somebody who I did not interview in person, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. He talked a lot — he talked a lot like you do about radical amazement, that the whole point of life is to be surprised and to be surprised over and over again and that spiritual life is about learning to be surprised. And here’s something he wrote.

“It is customary to blame secular science and anti-religious philosophy for the eclipse of religion in modern society. It would be more honest to blame religion for its own defeats. Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit, when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past, when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain, when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion, its message becomes meaningless.”

And I just read that because, when I read you talking about religion — and I really don’t want to debate it because …

Dr. Krauss: There’s no debate. I mean, we’re having a discussion.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, yeah, I do to. I feel like I’m not sure if you’ve been exposed to that kind of religious voice, which I think you would enjoy …

Dr. Krauss: I mean, I think it’s a brilliant statement. You know, wisdom is not the province of just — of scientists or of anyone. I mean, you know, and that’s a wise statement. Wisdom comes from experience and knowledge and understanding history and understanding the universe.

The reason to know things is in some sense to reflect on them and become wiser and it’s not the province of anyone. And people seem to think I suggest that it’s the province of science. Science is the raw material that provides the basis of wisdom for some people.

And so I don’t want to stereotype religion per se, and there are brilliant statements. I’ve often quoted them. I’ve gone into many places and fundamentalist colleges and Fox News and, you know, I quote Moses Maimonides and St. Augustine. I mean, they’re brilliant statements.

My favorite statement of Maimonides, more or less paraphrased, you know, as he said, the Scriptures are absolutely true. But if your interpretation of the Scriptures disagrees with the evidence of science, you should reexamine your interpretation of the Scriptures. There’s a lot of wisdom in all of that. What I’m amazed about is when someone as wise as that rabbi …

Ms. Tippett: Heschel, mm-hmm.

Dr. Krauss: … yeah, says those things, I don’t — what I don’t understand is why they need religion. I mean, if you’re a rabbi, at some level, you buy into the importance of Judaism. Many of my friends — one of their mothers-in-law is here today who …

Ms. Tippett: One of your mothers-in-law?

Dr. Krauss: No, one of their mothers-in-law, not one of mine. I only have one. They often say, well, you don’t have to believe in God to be Jewish and I say that’s absolutely true, but what’s the point?

I mean, there’s cultural wisdom. You know, there’s beauty in the masses that have been written for the church. There’s beauty in the paintings that Leonardo da Vinci and others and Michelangelo and others did in the context of religion, but that’s just the response to the culture of the time and I don’t see why, given what you know now, you can’t have that same wisdom without discarding the provincial basis of it, which was based, let’s face it, on the imaginings of illiterate peasants, Bronze Age peasants, before we knew the Earth even orbited the sun.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett with On Being, today at the Chautauqua Institution with physicist and public scientist Lawrence Krauss. I interviewed him in a week devoted to themes of inspiration, action, and commitment, including others like the Buddhist anthropologist Joan Halifax, the Muslim social activist Rami Nashashibi, and Homeboy Industries founder Fr. Greg Boyle.

Ms. Tippett: So one of the things that the other people I’ve been talking to this week, the other people who’ve been here at Chautauqua are all religious people who’ve been working and serving others, right, in compassion and …

Dr. Krauss: Doing much more useful stuff than I do. I’ll buy that.

Ms. Tippett: Well, you know, working with people who need help. And this concept of the other comes up and the problem human beings have with the other. And it’s a problem not just for religion, but for our society. You have talked about the other in these terms: that we are connected organically to everyone who’s ever lived, even our enemies, through the atoms and the oxygen we breathe. I mean, I think that is an example of science throwing this fabulous new light on something that vexes us.

Dr. Krauss: Absolutely, in a much more productive way than saying we’re all brothers under the skin or something.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: Because we really are, but it’s really amazing. Every time you breathe in, you breathe in atoms from virtually everyone who’s ever lived. Every time you take a drink of water, you’re drinking the secretions of every slimy thing that’s ever been around. You know, as I said in the beginning of the book Atom, my mother used to tell me when I picked up a glass of water, “Don’t touch that. You don’t know where it’s been.” She had no idea.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: But I think that’s exactly to me what science can provide is a realistic basis of understanding how artificial and myopic the definitions of us versus our enemies are. Not only are we made of the same things, we’re made of their atoms. And every atom in our body was once inside a star that exploded, one of the most poetic things I know about the universe, that we’re all stardust.

These are amazing things and they have content and they’re true. I mean, those three things are great. You can be amazed without the latter two. But I think when you get all three, it’s really something.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. We have to open this up for questions, because we are — this is so interesting and we’re running out of time. So let’s get going.

Audience Participant: How do you define love and from where does it come?

Dr. Krauss: Well, first of all, I’m not an evolutionary psychologist or neurologist or neuroscientist. But I think it comes, from my understanding and my effort to understand that, suggests it comes from many different areas.

It certainly comes from chemistry, hormones, not just sexual hormones, but many other aspects of what drives our perceptions of ourselves and others. It comes from logic as well. It comes from understanding. It comes from the effort to understand someone and find that they somehow mirror everything you like about nature, that everything you admire and respect.

I’m deeply in love right now, and I think the reasons for that is that the person I’m deeply in love with reflects all of those aspects of the universe that I admire. But I also realize that there’s many other aspects, physiological and chemical ones, that drive that, and I’d be a fool to think that I wasn’t driven by those physical processes.

Do we understand all of it? No, but that’s the great thing. Not understanding it is wonderful because it means there’s so much more to learn about what drives us as human beings to understand ourselves. And maybe when we do, we’ll be better at love.

Ms. Tippett: Yes?

Audience Participant: Thank you. Can you explain to us what dark energy and dark matter are and why — excuse me, how — it’s important to us?

Ms. Tippett: You have about two minutes for that.

Dr. Krauss: Well, they are almost everything in the universe. Let me make it quite clear that you are indeed far more insignificant than you ever imagined.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: Not just you, but you, not me, but all of you, but, uh, no, all of us, because we have learned that, if you’d look at everything we could see, the beauty of the night sky here and it’s nice and dark at night. I was looking last night at the stars.

The beauty of the night sky and everything we see is just a bit of cosmic pollution in a universe full of dark matter and dark energy. Ninety-nine percent of the universe, 30 percent of the universe roughly is this dark matter, which is made, we’re reasonably convinced, of some new type of elementary particle that doesn’t exist here on earth. Seventy percent is dark energy, which is the energy of nothing.

One of the reasons I wrote this book that you’re all going to buy, that empty space weighs something. It’s amazing. Who would have thought that? Empty space weighs something. And most of the energy in the universe resides in empty space.

Ms. Tippett: Space wasn’t really the right word, was it?

Dr. Krauss: What?

Ms. Tippett: Space.

Dr. Krauss: No, space is still there.

Ms. Tippett: It’s full, right?

Dr. Krauss: And it’s even empty. There’s not stuff in there. There’s nothing. You can look for it and there’s nothing there, but it weighs something. And what it really means, Krista, is that it changed what we mean by nothing. But there’s nothing wrong with that.

Science changes what we mean by things all the time as we learn. That’s what learning is all about. We change the meaning of things that we thought of before in a rough — and love. We may change what we mean by love when we understand it more, or morality or lots of other ideas that are at the forefront of our understanding.

But to get back to your question, so that’s the dominant stuff in the universe and everything we see is 1 percent. You get rid of everything we see, all the stars, planets, people, aliens, everything, and the universe would be essentially exactly the same. So much for a universe made for us. We’re just a relevant byproduct and that’s wonderful, that’s wonderful.

But the other reason you might care is that it’s responsible for our existence. We now understand that without dark matter, for example, galaxies would never have formed. It was necessary for that dark matter to exist and be different than the normal matter in order for galaxies to form and therefore stars and therefore planets and therefore people and therefore, theologians or whoever else.

[Laughter]

Dr. Krauss: And therefore it’s responsible for our existence. Now it will never produce a better toaster, I doubt. It won’t do anything useful and therefore you might say why should we care about it? What amazes me, to get back to the question you asked at the beginning, is why people ask that question. Because they never ask that question of why, what use is a Mozart concerto? What use is a Picasso painting? What use is James Joyce’s Ulysses or whatever?

Ms. Tippett: But, you know, that’s why we have to have people like you because we can’t take that in. We don’t know how to enjoy that. You can’t turn up like you can for a concert.

Dr. Krauss: You’re right. I agree. There’s a bigger barrier. But at the same time, you can enjoy it, I would argue, and most people just give up and scientists are a large part of it. Most people, when it says come to science, well, I just don’t understand it. They give up thinking, and that’s a really sad part of our culture.

You know, people don’t say, you know what? I can’t enjoy music unless I’m a musician. I can’t enjoy art unless I’m an artist. But you know what? Unless I’m a scientist, I can’t enjoy science. There is a great deal to enjoy and, of course, that’s one of the reasons why I do what I do. But we have to get over this idea that you don’t have to think at all. Well, you have to think a little bit.

Ms. Tippett: I want to come at this slightly different angle in just our last couple of minutes.

Dr. Krauss: OK, sure.

Ms. Tippett: One scientist talked to me about the spirituality of a scientist, and here’s how he described it. He said, “The spirituality of a scientist is like the spirituality of a mystic, which is that in any given moment you are discerning truth as best you can and you’re also completely aware that you have everything yet to discover.”

An evolutionary biologist who’s not religious recently said to me that he thinks scientists need to recover the word spirituality. He said we talk about it. We talk about the spirit of inquiry. So I just want to ask you, you know, very personally. Like, you know, if you did use that phrase, the spirituality of scientists, what would that mean for you?

Dr. Krauss: I think you’ve captured some of it. If I had to use the term, I’d use awe in the wonder of nature and the realization that spirituality isn’t having the answers before you ask the questions. And that’s the main thing: that real spirituality comes from asking the questions and opening your mind to what the answers might be.

Ms. Tippett: Lawrence Krauss, thank you.

[Applause]

Lawrence Krauss is professor of physics, Foundation Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, and Inaugural Director of the Origins Project, all at Arizona State University. His books include: The Physics of Star Trek and A Universe from Nothing.

You can listen again and download this show, and you can watch my unedited public interview with Lawrence Krauss on our website. That’s onbeing.org. Find all our Chautauqua conversations there as well as on our podcast at iTunes. On Facebook, we’re at facebook.com/onbeing. I’m on Twitter — @kristatippett. Follow our show @beingtweets.

On Being on-air and online is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, Susan Leem, and Stefni Bell.

Special thanks this week to Maureen Rovegno, Joan Brown Campbell, and the Chautauqua Institution. Thanks as well for production support on this show from Lily Percy.

Our senior producer is Dave McGuire. Trent Gilliss is our senior editor. And I’m Krista Tippett.

[Announcements]

Ms. Tippett: Next time, Alan Rabinowitz. A profound stutter as a child left him virtually unable to communicate and to prefer animals to people. He made his name as an explorer in some of the world’s last wild places. He has extraordinary insights into the animal-human bond, the evolving science of wildlife conservation, and what it means to be human. Please join us.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.