Living the Questions

A Civil Rights Elder on Exhaustion and Rest, Spiritual Practice, and the Necessity of Loving Community

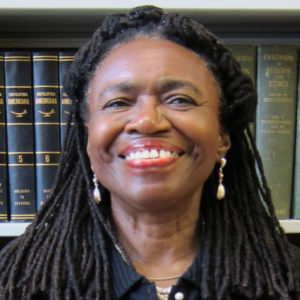

Our colleague Lucas Johnson catches up with one of his mentors, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons. Now a member of the National Council of Elders, she was a teenager when she joined the Mississippi Freedom Summer. She shares what she has learned about exhaustion and self-care, spiritual practice and community, while engaging in civil rights organizing and deep social healing. Dr. Simmons was raised Christian and later converted to the Sufi tradition of Islam.

Guests

Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons is assistant professor of religion at the University of Florida. She is also a member of the National Council of Elders. Her account of her work as an activist in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is featured in the book, Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

Lucas Johnson is Executive Vice President of Public Life & Social Healing at The On Being Project. He was previously a leader of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, the world’s oldest interfaith peace organization. Read his full bio here.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for readability.

Lucas Johnson, host: Well, good morning, Zoharah.

Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons: Good morning, Lucas.

Johnson: It’s good to be in conversation with you. Thank you for being willing to do this.

Dr. Simmons: Well, thank you for inviting me. You know, I did jump up, being the partial academic, and started reviewing some of my papers that I had written on this topic. Can’t help myself, right? [laughs]

Johnson: [laughs] Yeah, I understand. I understand.

Well, first let me say, we’re friends, and I know you allow me to call you Zoharah, but as my elder, I always am tempted to say “Mother Simmons” [laughs] or something, some sort of honorific for you. So if I end up slipping into that, then you’ll have to forgive me. Especially in a conversation like this, when you’re teaching me.

Dr. Simmons: I’m so used to that, so it won’t be a problem. Either way is fine.

Johnson: Or Dr. Simmons, of course, as well.

I wanted to talk to you today in part because we’ve been in conversation before about the ways that people are struggling right now. People are out there trying to do the work of social healing. They’re trying to do the work of holding our government and our communities to account. They’re trying to do the work of reconciliation in the midst of their relationships and their families. And they’re trying to just stay alive and survive in the context of a pandemic, and to stay healthy and to stay well. And I know that in the midst of this and these experiences, people are tired. And I remember, in conversations I’ve had with you, your experience of utter exhaustion from the movement years. And the work of healing that you needed to do. And I’m wondering if you can just share with me some of that experience, and what you felt like you needed to do to be well, in the midst of everything that was going on.

Dr. Simmons: Well, that’s an interesting question. I’m not sure that I’ve learned a lot about that. I certainly went through a breakdown right after Mississippi Freedom Summer, two years of that intense work in Laurel, and didn’t recognize that I was really about to break. Thank God, Jim Forman did recognize it and made me come out. I kept saying, “I can’t leave. I can’t leave.” And he said, “Well, you’re no good to that community if you’ve had a breakdown, physical or mental.” So he made me come out for a few months. That was imposed upon me.

The other time — when it really took a real toll on me — was into the third year of organizing the National Black Independent Political Party, which I threw myself into full-fledge while having a job and being a mom. I wound up in the hospital. I had adrenal gland failure, and they initially thought it was adrenal gland cancer. So that was a wakeup call. That would’ve been in about 1983. I took much more seriously, after that, the need to really take care of the body, the spirit, and the mind.

I certainly had already met my Sufi teacher, Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, and had been introduced to a number of practices of the Sufis. So I had to really get serious about a practice called zikr, which is the remembrance of God, as well as being very strict about diet and things of that nature.

Getting older and wanting to stay as fit as possible, mentally, spiritually, and physically, has required me to pay attention to physical exercise, certainly dietary — in my case, vegetarianism. Also prayer and meditation, both from the Sufi forms as well as my daughter introducing me to Buddhist meditation. That is something I’ve added. So those are things that I am doing, have done, to try and survive the pressures.

One thing that Sufism and Buddhism teach is letting go: staying at a distance inside while you continue with your work. But to really understand that you do all that you can do, and then you give it to a higher power to help you and those of you working for justice. Because really, as a believer, to me we’re doing God’s work. And this is the work of all of the religions, as I understand them. We are — as Dr. King was noted for saying — attempting to build a beloved community.

We have to internalize those teachings as well as work to change the structures of inequality, of racism, sexism, homophobia — all of the things that we’ve been working against to change in our society and our world. So it’s the internal work of really centering, and understanding that this is a much bigger thing than I can change. But that I can do my part.

Johnson: A few minutes ago, you mentioned remembrance of God. I’m wondering how self-care and rest relate to the concept of remembrance of God, for you. I think I can make that bridge in the Christian tradition, and also in the Jewish tradition. I don’t know about zikr and how that relates to self-care with respect to Sufism and Islam.

Dr. Simmons: Well, Islam is also one of the three Abrahamic faiths. So, while certainly there are practices that are different from what we have in Christianity and Judaism, for me, as a person raised as a Christian and only converting to Islam in my early 20s, I certainly have a sense of both traditions.

The whole idea of remembrance of God, or zikr, is both a practice and an effort to internalize the understanding that we are receptacles of God – or wisdom, light, whatever a person wants to call it — and that we are called upon to affirm that and realize that. As the physical form is the receptacle for this light, this wisdom, one has to take care of it; so that this light, this immanence, manifests through us and in our work that we do in the world.

Johnson: I know that some of the awareness that you’re describing is awareness that you came to after your years in the movement in Mississippi Freedom Summer and in other contexts. But can you talk to me about what that might look like in terms of spiritual practice, in the context of activism and organizing? What does that look like as we try to be in relationship with each other?

Dr. Simmons: An excellent question, and boy, I feel we are so challenged with regard to this, because one of the things that I constantly see amongst those of us who are progressive change activists is, often, how hard we are on one another, how unloving, unforgiving. We often attack one another. This harms our unity and our ability to be successful. So I think, first of all we have to start with the self. The self, the individual, certainly has to be constantly aware of one’s actions, how they impact on others, and do everything in their power to get rid of the negative qualities. There are two things going on. We’re trying to change the world, but we have to change ourselves, because we are a microcosm of the macrocosm. We must change ourselves in order to change the world. And that means a certain amount of reflection, really having quiet time with oneself to practice, maybe, a tradition, or just to sit quietly and think deeply and reflectively about the work that one is engaged in.

I was talking to some Black Lives Matter young people a couple years ago, and I was saying, “You really have to love the people.” I think this was one of the things that attracted me so much about SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and the SNCC field secretaries, as we were called. I saw such love for the people that we were working with and organizing. To me, this is indispensable. We must practice loving our communities that we are seeking to organize for change. I know it might sound sort of sappy, but this is the thing that I saw in Dr. King. Dr. King had great love, he really did. He had love for the people. And that’s what kept driving him.

I saw it in Vincent Harding — deep, deep love. And even in secular people like Jim Forman, Stokley Carmichael, I mean, deep love. And Malcolm X — deep love, deep. And we have to practice that with one another in our groups, and stop hurting each other as we build within our groups a beloved community, as we work toward the larger beloved community. Because if we can’t do it in our groups, how can we do it in the U.S.?

Johnson: I know that the SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) organizers would sometimes stay in communities, but SNCC was really known for moving in and becoming a part of the communities they were organizing.

Dr. Simmons: Absolutely. I was recently talking about my time in Laurel, Mississippi. There were just three of us, two guys and myself, and we split the list up. If they lived on the same street, maybe one would stay in the car, and one would go to one door and one the other.

And it was my great fortune that the door that I knocked on was a Mrs. Eberta Spinks. I was like, “I’m wondering if I could speak to you for a few minutes?” She was looking me up and down. I had on my blue jeans and my blue-jean jacket, which had become a uniform for SNCC organizers. And she said, “Are you one of those Freedom Riders?” I was like, “Uh, yes, ma’am.” She said, “Come in. I’ve been waiting on you all my life.”

That was literally the beginning of the Laurel project. I lived with that woman for two years in her home. I went to church with her almost every Sunday — I didn’t have a choice. We had to go to church, we had to live by their standards — no smoking, no drinking, that kind of thing — in their homes. But they were willing to follow us to jail, to beatings. It was really incredible. The love that I developed for Mrs. Spinks, I don’t know how you explain it – and for all the other people that I met and who became a part of the Laurel project.

Johnson: Well, it’s one of those things that Uncle Vincent, Vincent Harding, always used to try to help people understand, the extent to which the movement was a community that produced Martin Luther King, Jr. It was a community that moved this movement forward. It wasn’t just a collection of individuals. It was the Mrs. Spinkses. It was a movement that was about transforming — a spiritual struggle to transform the soul of America. It was so much deeper than what a lot of people understand.

I’m reminded of one of the stories that Uncle Vincent told me. Were you in Atlanta for Dr. King’s funeral?

Dr. Simmons: I was not. I missed that.

Johnson: But I remember the stories about how his body laid in state at Sisters Chapel at Spelman, and the wayUncle Vincent and many of the others, other friends of Brother Martin, as he would call him, stood guard over the body, so to speak …

And just the outpouring of love that was expressed for him, just the way that people would show up at all hours of the night to say goodbye to someone who they loved and who had loved them. It was also the way he made them feel seen and heard. So I feel like the love that was present in the movement and that sustained and carried people forward — because of what was at stake, you had to be committed.

Dr. Simmons: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Johnson: And they held you, because they knew that you were also risking your life, along with them.

Dr. Simmons: And in the case of Mrs. Spinks, she put up three of us. Two white women joined me. We went from a two-person staff to 23, and we were scrambling, trying to find homes for these volunteers coming in from all over, and two of them moved in with me, so we shared a room.

Johnson: That, in and of itself, was a crime, for y’all to be housed together like that.

Dr. Simmons: Oh, yes. And so Mrs. Spinks, that woman sat up a lot of nights with a shotgun across her lap, with the lights out. And she would tell us, “Now you all can sleep. I’m watching. And I’m not letting anybody bust up in here, not without a fight.” This is the kind of commitment that these people made. She had a husband in the house and a teenage son, and these two white women could’ve gotten them lynched. And yet, they did it. Amazing.

Johnson: And it’s the Mrs. Spinkses of the movement that nobody really talks about …

Dr. Simmons: Exactly.

Johnson: … or honors or knows. That’s one of the painful parts of it.

Dr. Simmons: And that’s why I have to call out her name, anytime I talk about the movement: Mrs. Eberta Spinks. I tell you, she belonged to one of the most prestigious churches there. It was built by Leontyne Price, who’s from Laurel, Mississippi. She sent the money back to build this really lovely church. It was the only one made of brick. So that minister was terrified of that church being bombed. And Mrs. Spinks was a member, and she got those sisters together, and they told him, “We’re going to have a Freedom School here. We are going to have mass meetings here. This is our church.” He had to back down, because Black women are the backbone — were and still are — of all of our churches.

It’s so many stories that people don’t know about the movement. People just want to focus on Dr. King, John Lewis, Rosa Parks. But this was a movement. This was the heart and soul of these communities that gathered together and put their hearts, their minds, and their wills into bringing about change.

Johnson: I think what I’m hearing is that a part of what sustained you in the midst of that was community …

Dr. Simmons: Oh, absolutely.

Johnson: … community, and the love and being held by community.

Dr. Simmons: Absolutely. And it often could get kind of funny, laughing-funny, in the sense that I’d have to say to some of the volunteers, “You can’t do that in this community. We respect how people live their lives here. You have to go to church with these people you live in the house with. I don’t care what your religion is, or no religion.” [laughs]

Johnson: Which is a hard — in today’s context, that would be — that’s a challenge.

Dr. Simmons: It was a challenge.

Johnson: It’s a conversation in and of itself.

Well, Mother Simmons, thank you so much for this.

Dr. Simmons: Oh, thank you.

Johnson: And I’m grateful for you; I’m grateful to have you in my life, and I’m grateful for your 76 years among us and all the wisdom that you bring. Thanks for having this conversation with me.

Dr. Simmons: And thank you for having me. I greatly appreciate it. And I so cherish you. You give me hope, because we’re marching on into the sunset, and we believe that we have young people like you who are continuing this work. And that gives me great comfort. Thank you.

Johnson: Thank you.