Living the Questions

Why 2020 hasn’t taken Rev. angel by surprise

A companion conversation to this week’s On Being episode — Krista catches up with Rev. angel Kyodo williams on how she’s keeping her fearlessness alive through pandemic and rupture.

© All Rights Reserved.

Guest

angel Kyodo williams is a Zen priest, activist, and teacher. She’s the author of Being Black: Zen and the Art of Living with Fearlessness and Grace and Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation. In 2020, she created the first annual Great Radical Race Read.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for readability.

Krista Tippett, host: Hi, angel.

Rev. angel Kyodo williams: Hi there. How are you?

Tippett: Ah. Well, [laughs] I’m glad to be hearing your voice.

Rev. williams: Good to hear yours.

Tippett: Where are you?

Rev. williams: I am in Oakland now — different Oakland than I was before, but Oakland. I moved right at the onset of all of the pandemic.

Tippett: You were moving as it was unfolding?

Rev. williams: California went into their stay-at-home orders on the 17th, and we were scheduled to move on the 18th.

Tippett: Well, I think, I’m sure Julie explained we’re putting our big, beautiful conversation back on the air. And I wanted to talk to you right now for just 20, 30 minutes, check in with you. I will say that listening to you again, to the conversation we had several years ago, it feels prescient. [laughs] It doesn’t just feel prescient. I don’t know that you used the language of “this moment,” but you said, “There is something dying in our society, in our culture, and there’s something dying in us individually. And what is dying … is the willingness to be in denial.”

And someplace else you said, “We are evolving at such a pace, what we’re experiencing now in our society, we’re just cycling through it. We’re digesting the material of the misalignment. We’re digesting the material of how intolerable it is to be so intolerant. We’re digesting the material of 400, 500 years of historical context that we have decided to leave behind our heads, and we are choosing to turn over our shoulders and say: I must face this, because it is intolerable to live in any other way than a way that allows me to be in contact with my full, loving, human self.”

I feel like you named something here, this evolution— we’re using this language of “the moment,” but we were already in “the moment.” We were building to this in all its complexity, which is not all pretty and not all hopeful, but it’s all of a piece.

Rev. williams: All necessary.

Tippett: I want to ask you how — and I want to ask you this personally, as well as in terms of drawing out your wisdom, your spiritual wisdom. I wonder if this surprised you.

Rev. williams: No, not at all. This body that we call a nation is ready for this. And any body that has had a great amount of toxicity as part of its system has to heave out that toxicity. And we’ve had a lot of ways to suppress it and a lot of ways to avoid it and a lot of ways to purchase things and distract ourselves and watch Netflix and all sorts of other things that we can do. And we have had a long history in this country, baked into the structure of the design — I talk a lot about the design of this country — to have so many people disembodied. We had an amazing, extraordinary, painful, and yet, collective experience of a sufficient quieting that allowed us to feel this collective body that we are as a nation. And there’s a whole bunch of individual bodies in there that said, “Enough. I can’t tolerate what is here, because I can feel it now. I can see it.” And the uprisings and the particular potency of George Floyd’s — not only his death, the means of his death and the expression of his death. And I mean that literally, the expression; the physical embodiment, the expression on the officer’s face, the expression of his death through the media. The expression of his death was too much for this body to continue to bear.

Tippett: I also think about how soft we were, as a collective body and in our individual bodies. We had, each and every one of us, in whatever the circumstances of our lives, kind of felt for the ground beneath our feet. And our defenses were down.

Rev. williams: The pandemic created a forced retreat. It’s like we were on forced retreat. I’ve done retreat for many years, and there’s always this point during retreat where you feel your not-knowing come into your view. It’s one thing to move around the world and say, “Oh, I don’t know,” to have not-knowing. It’s another thing to just feel it — to come into confrontation with your not-knowing. It is tender, like you said. It is a tender place to be in confrontation with that. And it’s different, entirely, to have it be not just individual but to also feel the reverberations of the collective not-knowing. As a country, we’ve never been in anything, in this generation, that has been experienced so potently as collective. I think the presidential election is something that we’ve experienced as a collective. Similarly, there is real splitting in terms of where it lands in our bodies. And yet, it was a collective experience.

Tippett: I’m curious how, just for you on a personal level, how did this land? What has it been like, where did it land in your body, and what’s your trajectory been with this time?

Rev. williams: I feel like I’ve been preparing for this — not for George Floyd’s death; Black people being assailed with impunity, violence and aggression upon our bodies is not new. And when Eric Garner’s murderers were acquitted [Editor’s note: The Department of Justice declined to bring charges against Daniel Pantaleo, the police officer implicated in the chokehold death of Eric Garner.], I feel like all of the Kool-Aid left the back of my throat — all of the Kool-Aid that was like, oh, we’re in a different time. It was like, oh, we are not. We’re in a different shade of history, of times that repeat themselves and cycle themselves.

From that point on, I got serious about trying to understand how to be prepared for what I felt, in order for me to live — I had to feel that there was eventually going to come a time when white-bodied people would not bear this anymore. And so how could I participate in advancing that, and how could I participate in being ready to respond and have something to say to people when they got here?

Tippett: And I think that is what, actually, we hear, listening to things you said a few years ago — that you were actually speaking to now.

Rev. williams: Well, we often talk about prophecy as people talking about something about the future. And I always think that prophets are talking about now. That’s part of what makes them dangerous, because we are mostly living in the past. We are mostly inhabiting the past, and prophets name what’s actually happening now. So we turn around, and we look, and we go, “Oh, they were saying something prescient.” It’s like, no, they were just talking about now. [laughs] They were talking about now, and then we catch up. We catch up to the truth of the experience that we are in. We catch up to the truth of what is actually unfolding that we can’t reconcile with yet, and then we come to a point in which we begin to reconcile the truth of our experience.

Tippett: Something that’s very much on my mind is the overwhelmingness of news and what’s happening. We have multiple ruptures. But what I also see is — you also said this several years ago, and I agree — that this is an evolutionary moment. I believe that. We’re also captive, though, to the story of the time as it’s being presented. I’ve been pretty good at not reading lots of news, in general, or going to social media to see what’s been happening in the world. But in these months, it’s been hard not to check in on what happened today. What happened this morning? Is there something new? We’re so captive to what is being seen and presented. And to me, there’s this real spiritual discipline of where we’re looking; what we’re seeing; what we’re taking seriously.

I’m just curious, where are you looking? What are you seeing? As you make sense of this evolutionary moment in its fullness — which is not to not give absolute seriousness to very particular things that happen on particular days, but to see it in that evolutionary light — what is that spiritual discipline as you practice it as a human being?

Rev. williams: I practice reading the news, just consuming news. And that has been part of this experience: I didn’t have a sense of wanting to know what was happening, but wanting to know what we’re saying about what is happening. Maybe it’s fallen off a little bit, I think, and has for many people. I had been reading voraciously, because I wanted to know, how are we making sense of this? That is what I’m trying to do, is track how are we making sense of things, and what is missing in our sense-making? What are we missing, at any given moment in our sense-making that is leaving these enormous gaps in our embodied experience, in our ability to tell the truth to ourselves?

So I lean in — [laughs] that’s my discipline: lean in. I read it, and I don’t give myself a bunch of trouble about it; it’s just like, I read it. I read across different types of media so that I’m not stuck with one particular voice. Then I pull back from all of it and understand it as of a time, and try to keep that in perspective with “This is of a time; we are in a cycle.” I believe we all feel now, clearly, both the potential, and also, the desperation of this unique moment. There’s both enormous potential, and, because there’s so much potential, there’s also real desperation. That is being read from everyone touching this moment. What the storyline is, for them, is different, but there’s a real potential. That is so clear. I think that that’s why there’s such a vehement division and digging-in, because there is potential. It’s so clear. We’re at a turning point.

I turned on the various channels to watch the marches, and I was like, oh, this is different. This is different. This is not the protest that will happen and we’ll clamor about the numbers, and then we’ll go back to business as usual. And the pandemic gave us the opportunity to have the kind of rising that happens in a body that makes that decision of, am I in? Am I in? Yeah, I’m in. So we saw this rise; and I felt that rise. And there were points at which I just pulled back away from it so I could feel it in the air, if you will, rather than just watching it. Am I feeling something different here? And I feel something different. I feel so clear.

There’s always gonna be backslide, because we’re so prone to going back to what’s familiar. But there are people, through a lot of years of work — decades of work, [laughs] and particularly the last five, six years, the Black Lives Matter movement work — this is the work of people’s response to their being everywhere from dismayed to disgusted about politics, and their willingness to say, enough. There are many people that once upon a time I would’ve said, “Yeah, they’re just gonna go back to sleep.”

Tippett: But that feels new? That feels like it’s not gonna happen this time?

Rev. williams: I feel so clear. So that’s where I spend my time now: watching, being connected with people, and listening deeply to what is different about their tone, their commitment, their sense of what they’re being about right now. And it is really different. [laughs] I mean, it’s really different. I think it’s different in all directions. I’m not saying there’s just one “different.” This is a very different moment.

Tippett: I love hearing you — you — say that. I also really appreciate the nuance of that leaning into the story that’s being told of our time in different places, which is what we call the news, and letting it in, but letting it in as not “here are the facts.” Also because when we let it in as “this is the truth” or “this is what the other side is saying is the truth,” then there’s this reaction going on or this identification. But by asking, how are we making sense — and how is this particular corner of the world making sense — there’s a curiosity and a humanity to that. And there’s a detachment — a good Buddhist value. It’s so much healthier than the attachment.

Rev. williams: I’m curious about how people that watch Fox News are making sense of this. I’m deeply curious about how we unfold the narratives of our lives that we live by. How is it that we unfold those narratives? How do we take in what appears to be “the same information”? We’re so desperate to cling to the idea that there’s a truth, and some people tell the truth and some people don’t tell the truth — that’s true, right? [laughs] But there’s also the simultaneous, co-arising, conflicting, operating-at-cross-purposes truths that some people really experience their truth as totally their truth. I don’t think what we’re in is that there are a bunch of people committed to just telling a very false story. I think there are many people committed to “this is what my truth is,” and they’re deeply, deeply immersed in that truth. And polarization, no matter where you stand on the aisle or the sides or the colors, digs us further into what we believe to be our truths. So there is something that is being called for from all of us, I think, to transcend our truth — little “o,” “our” truth — to find Our Truth, which is a big “O” and a big “T.” And that requires a lot from us.

Tippett: And that understanding, the fierceness with which one truth is held, as a way of making meaning — approaching that is a different way to approach the other.

When you and I spoke before, you used words like “faith, hope, and love” — [laughs] what you expect from a New Testament theologian, talking about the book of Romans. But you used all those words, vividly. I thought the one I might ask you about, another important virtue or way of being in the world, is your notion of fearlessness. As we draw to a close, I would just like to know, what does fearlessness look like to you now? What is it in your body, and how do you nurture it? How do you cultivate it in this now?

Rev. williams: The way that I live into the idea of fearlessness is that we have always, in front of us, a possibility of how it is that our life is going to unfold. And then there is the reality as we experience it. [laughs] There’s both this possibility and there is the reality we’re experiencing. The distance between the reality that we experience and the possibility is the actions that we take. And those actions that we take are rooted in how firmly we are grounded in that possibility.

So I often think about the possibility of America that has never existed for most of us. And what it takes for me to think about being able to continuously have a sense of meeting the energy, meeting the fire, meeting the pain of what America is — and the ways that it has failed me and failed so many people — is to stay really grounded in the possibility that it can come into being. That I need to be fearless. I have to have a kind of fearlessness around holding that possibility that wasn’t dreamt for me, that wasn’t structured for me, that no one designed for me — that that is my possibility, too. And I am the one that gets to take the actions to unfold that for me.

So, in the same way that there are some people who really, really believe that this country, this nation, the world belongs to them, and there are certain ways that it should be shaped, and I should be located in certain places in it, I hold with fierceness the possibility that there is a new America that depends on me being absolutely rooted in this sense of fearlessness about the possibility is mine. It’s always available to me. It depends on me, and I’m not waiting for anyone else to bring it about.

Tippett: And even when we do the best actions or the best actions we see, there’s also a lot of injustice — you could even look at the hazards of the natural world. There are a lot of things that happen that thwart our best actions. So I really wonder, personally, how do you cultivate this fearlessness? How does that work, and how do you keep that alive, that fierceness, which has to coexist with, also, the chaos of existence and the unpredictability that feels especially acute right now, of what will happen next? How do you keep that?

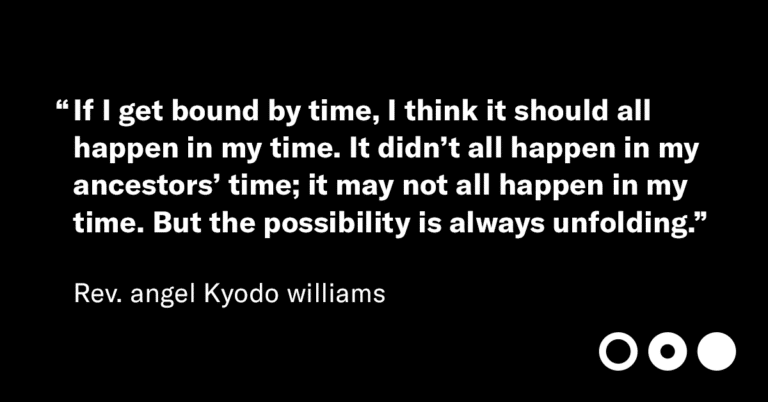

Rev. williams: We have this idea of emptiness, and a lot of people in the Buddhist tradition — particularly Zen — talk a lot about emptiness. And because of the way the Western mind thinks, we think empty, and it goes right to “less”; it means “less.” I like to think of the same character or the same concept of emptiness as “boundless.” When I think of the sense of boundless, I feel that I’m not bound by time. So in any given moment, I am living on behalf of my ancestors and all that they did to arrive at this moment. My existence is proof that my ancestors’ sense of fearlessness about their possibility actually came to be.

Tippett: Despite everything that happened to them.

Rev. williams: Despite everything that happened to them. I’m proof. I’m living proof in this moment. And, therefore, in any given moment, all of the possibilities that exist — my actions that are given over to the future — are also happening right now. I’m not bound by time. I’m past, present, and future. So if I get bound by time, I think it should all happen in my time. It didn’t all happen in my ancestors’ time; it may not all happen in my time. But the possibility is always unfolding.

Tippett: And do you have specific practices that help you cultivate that way of thinking and seeing, or is this just so ingrained now in all your practice?

Rev. williams: I think it’s ingrained in all my practice, and I have particular practices that I’ve really lived with, this sense of returning. I think of it as really returning to what matters. If I’m honing and refining and being really attentive to what is it that really matters in any given moment, the things that seem excessively important in a moment fall to the wayside when I think about my contribution to the future, when I think about my contribution to what is to come. Whatever is happening that feels like this annoyance, this frustration, this difficult person, this person doesn’t agree with me, this person doesn’t have my interest in mind and interest in heart — I can live and transcend this moment and live beyond that person, beyond that moment. And my actions come from there, from being able to return, over and over again, to what matters. And I really try to stay — or, not stay. I want to be really clear. I don’t try to stay in what matters, I return to what matters. I return.

Tippett: Well, thank you so much. Thanks for being out there and doing your part for our common future, and for your teaching and just your presence. It’s really wonderful to speak with you again.

Rev. williams: It’s good to talk to you. And I just want to say, I feel so clear that there are way more people that are participating in this unfolding that is happening right now than has ever felt true to me in my lifetime. So I’m really, really happy to not feel — I never felt alone. [laughs] I felt not alone only by faith, and now I feel not alone because there’s real, tangible experience of people wanting to decide that we want to be in our humanity. We want to be reconnected to each other in ways that we’ve never been allowed to be connected before. And I feel really, really positive and hopeful about that.

Tippett: I feel like that’s such a reality check, what you just said. A certain kind of seeing all of this could see it as hopeful and Pollyannaish, but instead, I think, it is a reality check. It’s pulling back from all the interpretations and the focus, and telling it like it is, in the — what was the word you used? Not emptiness, but …

Rev. williams: Boundless.

Tippett: Boundlessness — in the actual boundlessness of reality.

Rev. williams: If we can stay there — I mean, not stay — if we can return. We have to leave — [laughs] we’re humans. We have to get down to the business of tying our shoes and taking care of babies and things. But if we can return to our sense of boundlessness, it brings everything into perspective, which doesn’t take away the pain of the moment, but we don’t have to live into the pain, we can live through it.

Tippett: angel, thank you so much.

Rev. williams: Thank you.

Tippett: Blessings to you.

Rev. williams: Blessings to you. Hope to see you soon.