Maira Kalman

Daily Things to Fall in Love With

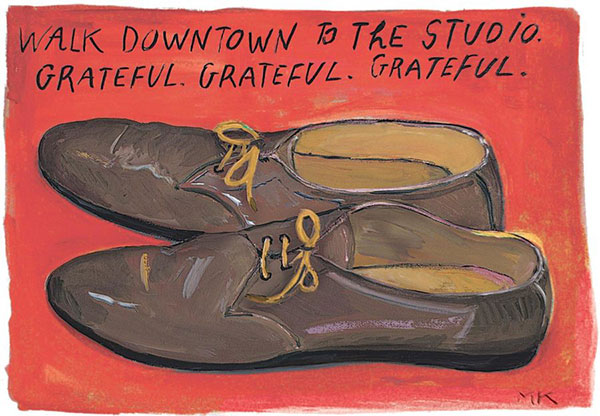

Writer and illustrator Maira Kalman is well known for her books for children and adults, her love of dogs, and her New Yorker covers. Her words and pictures bring life’s intrinsic quirkiness and whimsy into relief right alongside life’s intrinsic seriousness. As a storyteller, she is contemplative and inspired by the stuff of daily life — from fluffy white meringues to well-worn chairs. “There’s never a lack of things to look at,” she says. “And there’s never a lack of time not to talk.”

Image by Maira Kalman, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Maira Kalman is the author and illustrator of over 20 books for adults and children. She is well known for her New York Times blogs that have become books like And the Pursuit of Happiness and The Principles of Uncertainty.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: “The subject of my work,” Maira Kalman says, is “the normal, daily things that people fall in love with.” She is a visual storyteller, and to be in conversation with her is a little like wandering into one of the cartoons you might see in The New Yorker and which she might have drawn. Millions of us have been prompted to smile and think by Maira Kalman’s work in a museum or the recent illustrated revision of Strunk and White’s Elements of Style or a New York Times blog or her lovely books and her drawings about dogs. Her words and pictures bring life’s whimsy and quirkiness into relief right alongside life’s intrinsic seriousness, its most curious truths.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Maira Kalman: The way that we move through space is really interesting to me, and I am conscious of the fact that we are moving and dancing, in our way, all day long. It’s funny, because Nietzsche said that a day that doesn’t have a dance in it is a lost day, which you wouldn’t expect from somebody like Nietzsche, who was crazy.

Ms. Tippett: And intense.

Ms. Kalman: And intense and had such a giant mustache, as I write about. But the fact is that we really are all moving and dancing all day long. And the older you get, the more dangerous it is. And you can trip. I tripped on the sidewalk and broke my arm, and I thought, “Well, how did this happen? This is absurd.” So my heart goes out to everybody — that’s it. My heart goes out to everybody.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Maira Kalman is the author and illustrator of over 20 books for adults and children. She is well known for her New York Times blogs that have become books, like The Principles of Uncertainty. She grew up in the Bronx and now lives in Manhattan. We spoke in 2017.

Ms. Tippett: You were born in Israel, it sounds like, but you came to New York at the age of four. How would you describe the spiritual background of your childhood, however you would define that?

Ms. Kalman: It’s interesting because, really, all of my work goes back to my childhood, as many people can say about their lives, and even the childhood of my mother in Belarus. I’m constantly relating to and living in the family — the stories, the light, the air, the sea, the cafés, the fluttering awnings. All of that resonates so strongly for me in all of my work, and I’m painting and writing about it all the time and even more so now.

Ms. Tippett: I think that’s right, that so much of who we become, and even the questions we follow all our lives, go back to that. But I feel like you’re more in touch with that than a lot of people.

Ms. Kalman: It’s relentless, whether I like it or not.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right, you’re relentlessly in touch.

Ms. Kalman: I’m relentlessly in touch with something wonderful, which I guess is a good thing. But it’s so profound and so wonderful and so sad and so everything that I can’t stop it. It just gets richer and richer.

Ms. Tippett: It was your mother’s family that came from Belarus, is that right?

Ms. Kalman: Both my father and my mother, they just came in different times, and they met in Israel. But they both came from little villages not far from each other, actually, which I went to visit a few years ago.

Ms. Tippett: I don’t know how you describe yourself. When people call you a visual storyteller, that feels like a good pointer to me. Where do you trace the roots of that in your early life?

Ms. Kalman: It’s really such a lovely and erratic tracing. I really thought that I was going to be a writer, and everything was born of that. I read Pippi Longstocking when I was 8 years old, and I thought, “That’s it, I’m going to be a writer. I can do that.”

Then my writing became so heavy and laden with angst and misery and confusion, and so tedious that I thought, “This can’t be the right thing to do. I want to do something fun and easy, and that might be drawing.” My sister was an artist, and I thought, “Well, that looks like a tremendous amount of fun,” even though, of course, the artists were very miserable. But I thought, “I can do that.” So my writing informs my painting, and the painting informs the writing, and they really are connected in very intimate and vital ways.

Ms. Tippett: It’s so interesting that you describe your early writing as angst-ridden because that’s so different from the words someone might use to describe your books, your illustrated writing now.

Ms. Kalman: Right, well, the angst is invisible. I worry and suffer tremendously, I must assure everybody. But I just somehow am able to eliminate that and come across as a very optimistic and joyous person, which, in fact, I also am. So I’m completely confused.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Yeah, right. Well, I would say — I don’t know if I would talk about angst — and we’re going to talk about this — you touch on very serious subjects, very deep, serious parts of being alive, but somehow hold it in this context of pictures and words which are also whimsical and playful. That’s kind of what you’re saying. I would say that one of the things that really struck me as a theme, a thread, as I looked at your body of work, is that you actually hold together contradictory experiences and impulses that are the very vitality of life, but that we often treat as opposites — so angst and whimsy.

But also, I would say, another one, just thinking about how I’ve seen you talk about how you spend your days, how you organize your life and your art — on the one hand, what at least looks, on the outside, very much like this great spontaneity, this ability to follow your nose and then work with that. But also, you adore ritual. Those two things work together for you.

Ms. Kalman: It’s taken me these many years to understand that a human being can encompass very contradictory ideas and feelings at the exact same time. They’re not separate; they don’t even follow each other so much. They just live in you. For me, to clarify what I love, to do what’s amazing, to understand my confusion or my sorrow and to still continue to — the thing about it is that you persevere. I do follow my nose, and I do have many rituals that I love following, and I love breaking the rituals, so I’m not a prisoner of the construct of my day.

Sometimes, I’m spending too much time wandering around when I actually have work to do, but I always say that’s — “Oh, well, this must be the work that I need to do right now, before I do that other work.” And really, I think, the more that I work and the more that I see what my life is, the more simple it becomes — and very elemental. I mean it’s very boring, actually. If most people had to live it, they would go, “Oh, that’s it?”

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Let’s talk about how you start your days. It’s interesting to me; I think you don’t do this anymore, but for a while, you used to read the obituaries at the beginning of the day.

Ms. Kalman: Oh, that’s my religion. That I won’t break, every single day.

Ms. Tippett: Do you still do that?

Ms. Kalman: That’s the first thing, coffee and the obits.

Ms. Tippett: O.K., how’d that start? When did that start?

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] It started when I was born. I don’t know. It started so many years ago, because — of course, the essence of people’s lives, what happens to them in several hundred words and a few pictures, is really an extraordinary way to start the day, to see what the range of human endeavor is, from what seems to be trivial to monumental — but none of those are ever trivial, and monumental, sometimes, is even less interesting — but that there is a great sense of hope in these obituaries because people have done amazing things.

Ms. Tippett: Somewhere in The Principles of Uncertainty, you have this place where you say that you read the obituaries at the beginning of every day: “Maybe it is a way of trying to figure out, before the day begins, what is important. And I am curious about all the little things that make up a life.” Do you have some favorite obituaries or obituaries that come to mind that have struck you recently, just as an example?

Ms. Kalman: Recently, I just read the obit of a Hungarian woman whose family escaped the Holocaust, and she ended up marrying a cousin of Nehru and lived in India and had this extraordinary life. I love that one. What else was recently amazing? Whenever I think of the best obituaries, I think of the man who invented the Bundt pan, whom I have in my book.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right. Oh, there’s another one, Megan Boyd in Scotland. Do you remember that one?

Ms. Kalman: Yes, Megan Boyd, who created the flies for fly fishing her entire life and lived in a little village. She had a fantastic obit and a beautiful photo that I did a painting of.

Ms. Tippett: But it was also very intricate, long work. It sounds so romantic when we say it like that, and, in fact, history-making, in a way. But it was also the care and the detail.

Ms. Kalman: Well, that’s, once again, the perseverance of work, the insistence that you keep doing it, and you continue no matter what and through bad periods and better periods. So there she was, sitting at her bench 16 hours a day, and when she was invited to Buckingham Palace, she said she couldn’t go because she had to go to a dance in the village. And I thought, “Now, this woman is a genius.”

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right, yeah. So you read the obituaries, and then do you walk every day, walk in the park?

Ms. Kalman: Yes, I meet a friend, and now it’s 20 years that we have walked three times a day in Central Park. The other days, I try to walk, but I’m not as motivated without her; she’s a great companion. And then we have a cup of coffee. She’s a doctor; she goes and saves lives. And I don’t know what I do. I save myself, or I help other people live. And in between, after we finish the coffee, I take the bus down Fifth Avenue, and then I’m probably the happiest person on the bus. And then I say, “in New York.” And then I say, “in the United States.” And then I say, “in the world.” It’s really extraordinary. When we’re in the park — and there aren’t that many people there, and we go all year round — we think, “Where is everybody? How could they be so stupid as not to understand what they have here for themselves?” But there you go.

Ms. Tippett: Here’s another line of yours I love: “We see trees. What more do we need?”

Ms. Kalman: That’s really true. It’s really hard to be sad. And of course, I’m always looking at the things that make somebody less sad, a.k.a. happy, which is not “a.k.a.” at all. So walking and looking at trees really is one of the glories of the world, and we say “Rejoice” when we see these things. We say that when we see people walking and going about their business, but something about trees — they’re very hard to paint, by the way, but I’m happy to try.

Ms. Tippett: And again, I guess I’m speaking for myself, but I think I’ve also heard plenty of people talking about really important moments of their lives that had to do with pondering a tree. It’s amazing to me that trees are just — they are so perfect and gorgeous and amazing, and they just are.

Ms. Kalman: They just are.

Ms. Tippett: They just are. They are, whether we’re looking at them or painting them or admiring them or not, or whatever the weather is. But I don’t think most people — even as I say that about myself, I don’t put myself into that position to be adoring them and letting them make me be happy and get some perspective on my life. [laughs] But you put yourself out there to do that.

Ms. Kalman: Well, you know, you can always start.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] That’s true.

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] And, you know, leaves grow on trees, and birds sit in trees, and birds sing, and it’s a whole beautiful package.

[music: “Like a Honeybee on Holiday” by Lullatone]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the visual storyteller Maira Kalman.

Ms. Tippett: We touched on this a little bit when we touched on angst at the beginning of our conversation, but another juxtaposition that you hold together, and you hold together as vitality, is life’s intrinsic whimsy and quirkiness and, also, life’s intrinsic sorrow.

Ms. Kalman: And actually, I wouldn’t attribute the whimsy and the quirkiness. I would say it’s completely inexplicable, random, confusing, fragile, fragmented that we impose — I impose, in my way, a sense of humor about it all, of course, but I don’t know what the world offers. The world offers so many different things that are really incomprehensible. So the take that you have on it, of course, is what happens with the rest of the day.

Ms. Tippett: Right. I didn’t see this anywhere else — obviously, I haven’t read every single word, but there’s one place, and I believe it’s in The Principles of Uncertainty, where you say that your mother did not marry the man she loved but, instead, your father. Is that right?

Ms. Kalman: That’s true. Yeah, it’s sad. I think about that a lot because I was so close to her. My father was away a lot. He traveled half the year, not consecutively, but he was really gone a lot. The women were left, as I say, to their own devices, which in our case was kind of wonderful because he was a rather, in the old form, patriarchal man who ruled as the patriarchs did in those generations. So when he was away, we really flourished in a way and found out what it was like to be a woman, to be a young girl, to be a woman, and to just be who you are.

Of course, there are so many sad things about that, but I think that the strength of the women in my family was so formidable, even in their sorrow or suffering, that something registered in me that said, you can observe really unhappy relationships and still find a good one. I found a fantastic relationship with my husband, so I think probably one of the things I learned was what not to do. So that’s a good lesson. You can watch closely and say, “Aha, this is not going to happen to me.”

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, well, that’s good. But it can work both ways. Did you know when you were growing up? Was this a story your mother told about herself, about this man?

Ms. Kalman: No. My mother never said anything about anything negative. It was really from other people in the family and family lore that you just absorb through the years that she was madly in love with somebody else, and the fates did not allow it.

Ms. Tippett: Again, for all the beauty and playfulness and — what is it you say? “The subject of my work continues to be the normal, daily things that people fall in love with.” And then you also are very open about thinking a lot about death and fearing death. Has that always been true?

Ms. Kalman: Who doesn’t? Krista, who doesn’t? I’m always amazed if somebody says, “You think about death so much.” And I say, “What are you thinking about?” I mean [laughs] I can’t imagine.

Ms. Tippett: I thought about it when I was getting ready for this. I don’t know that I do think about it. I mean, I have all kinds of fears. It’s not that I don’t have fears and anxieties, but not in the way it comes out in your work.

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, I think you’re lucky.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] O.K.

Ms. Kalman: You know what? Of course, it has a lot to do with the family history, which is — especially from my father, who left Belarus, and his family didn’t leave, and they thought, “What could go wrong?” And they were all killed. That’s what went wrong. So I was brought up on the idea that everything could disappear — and this is nothing, obviously; many, many people have this — that all could be lost in a nanosecond, that you’re never safe, and that tragedy and literal killing is part of the possibility, and especially going to Israel and having the sense of, again, being warriors in the defense of a nation that’s being attacked, historically.

Of course, things have changed so dramatically now. It’s intensely complicated to even discuss it. But from the point of view of people who were escaping the Holocaust and coming to Israel, the sense of “We cannot let this happen again.” So that somehow very clearly enters into the persona of “Wow, my family was killed.”

Ms. Tippett: Well, it’s in your DNA is what we’re learning, right? It’s literally in your body.

Ms. Kalman: Right.

Ms. Tippett: Right. And then your husband died at 49, which is so young, although you had such a good long time together.

Ms. Kalman: We had an extraordinary life.

Ms. Tippett: Three decades?

Ms. Kalman: Yes, and I think, how fortunate, how completely amazing that we met in summer flunk-out class at NYU in the late ’60s, when everybody was doing everything except going to school. We had such an amazing time and had a family, had two children, and worked together and really were each other’s muses and support in every way. I am profoundly grateful to have had that relationship and to have somehow been with a man who was very courageous and taught me how to be brave.

Ms. Tippett: Because he was brave? Did he teach you by being that?

Ms. Kalman: I always used to say he was fearless. He didn’t ever think anything would stop him, ever. It just wasn’t in his vocabulary. When you live with somebody like that, it’s very interesting to say you that have an idea, and then if you don’t act on it — well, why wouldn’t you? It sounds very simple because, of course, some things don’t work out, and it’s not always such a straight line. But you live in a different — you’re breathing a different kind of air.

Ms. Tippett: There’s a passage where you write and illustrate about — you start with Gershwin, dying at the age of 38 of a brain tumor. You say, “He’s buried in the same cemetery as my husband. My husband died at the age of 49. I could collapse, thinking about that. But I don’t want to talk about that now. I want to say that I love that George is nearby under a leafy tree. And Ira Gershwin too.”

Ms. Kalman: We’re going to visit him next week, and the high point is [laughs] — we can say, “I like visiting Tibor, but the high point is going to the Gershwins.” No, also, the Barricinis are nearby, and I always think of a beautiful box of chocolates and how they should have a chocolate store there in the cemetery because it’s actually very uplifting to go to a cemetery, and it’s a beautiful place.

Ms. Tippett: Yes, it is.

Ms. Kalman: And so somehow, things fall into place in a nice way. And it’s good to visit him.

Ms. Tippett: It was also interesting to me — you’re beloved, known, also, for Max Stravinsky, the poet dog, and your writings about dogs and your books about dogs for children, but also writing for adults — that you actually got your first dog, Pete, when your husband, Tibor, was dying from cancer. So there was the connection to that.

Ms. Kalman: It was really profound. And of course, I was terrified of dogs before that and would never entertain getting one, but we decided that for the sake of the children, it was really incredible to have a dog who would be a great mood elevator. I just didn’t realize that I was probably the recipient of the most mood elevation from Pete.

Ms. Tippett: You wrote in Beloved Dog — I thought this was wonderful. I’m sure many people who love dogs will resonate with this — “They are constant reminders that life reveals the best of itself when we live fully in the moment and extend our unconditional love. And it is very true that the most tender, uncomplicated, most generous part of our being blossoms without any effort when it comes to the love of a dog.” [laughs]

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] That’s right. My children have something to say about that.

Ms. Tippett: What do they say?

Ms. Kalman: Well, they want to know who I love more, of course. They’re not such children anymore. But I think that when they were younger, there was a little bit of a “So who do you really love over here?” But because of the simplicity of it, because of that, we can do that really easily.

Ms. Tippett: The love relationship with our children is complicated because they are complicated.

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, they can speak.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] They can speak.

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] That’s a big problem right away.

Ms. Tippett: But I also love how you name dogs as natural comedians.

Ms. Kalman: Yes, of course. They’re very funny. Of course, when I started looking at them, when you’re walking down the street, they’re heroic, and they’re comic at the same time, which I guess is my favorite way of looking at things.

[music: “Cleaning Rooms With Inez” by Mark Mothersbaugh]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more with Maira Kalman. We’re putting all kinds of great extras into our podcast feed — lots of poetry, music, and a new feature “Living the Questions.” You can get it all as soon as it’s released when you subscribe to On Being on Spotify, Google Podcasts, Apple Podcasts — or wherever you like to listen.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the beloved visual storyteller Maira Kalman. She is well known for her books for children and adults, her love of dogs, her New Yorker covers. Her New York Times illustrated blogs become books with titles like The Principles of Uncertainty. Maira Kalman’s words and her pictures bring life’s intrinsic quirkiness and whimsy into relief right alongside life’s intrinsic seriousness.

Ms. Tippett: I think what people love in your work, also, is that you are a real connoisseur of the art of laughing at oneself and, also, making other people laugh. I think that must be a very joyful thing to be able to do.

Ms. Kalman: It is, and I probably understood that when I was quite young. Maybe that was one of the things that I decided I needed to have in the face of whatever craziness was going on in my family, having a sense of humor. I think, also, maybe, coming from another country and just observing and having a sense of pleasure and joy in learning a new language and watching people. And of course, in my family, everybody had a great sense of humor, so it wasn’t as if I invented it in my family. That was the language of conversation, that you told funny stories.

Ms. Tippett: Really?

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, especially from people who come from the Russian — [laughs] the tragic Russian writers. But, as we say, always, hand-in-hand with that was a stupendous sense of humor and a sharp wit.

Ms. Tippett: Do you have a meditation practice?

Ms. Kalman: I have a limping —

Ms. Tippett: I know that’s kind of a personal question, but I’ve seen you writing about —

Ms. Kalman: No, no, it’s fine. The good news is that there’s nothing personal about it. I was hired by a wonderful editor, Barry Boyce at Mindful magazine, to meditate and to do a column about meditation. So I always say I was paid to meditate, which I think is not a bad way to encourage somebody to do it.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] That’s right.

Ms. Kalman: I went on a few, very short, silent retreats, a few days, and I was taught the practice of meditation. And then, I wasn’t flippant about it. I really enjoyed it, and I really understood the value of being able to calm your soul and steady your anxieties, especially in the middle of the night. I’m immensely grateful that I have this practice, which I don’t do regularly at all, on the bus or walking here or waiting on line or something like that, or in the middle of the night. So I think that it’s non-spiritual, and it’s non-religious, which is really important for me, because I don’t like any religious dogma at all. And I value the sense that it’s humanistic.

Ms. Tippett: Right. And actually, I feel it’s something you both portray in your work and model, is honoring meditative spaces or even contemplative spaces in the everyday, but also in public life, like parks or museums. I think of libraries in this way as well. Do you think about it that way?

Ms. Kalman: I absolutely think that a museum is one of the deepest places of meditation that there could be, maybe even more than a library, because you’re looking. In a museum, you’re not reading — I mean, you’re reading a little bit, but you’re basically just wandering and looking. And once again, the function of the brain, what happens to the brain is very different than, I don’t know, than being in a supermarket — even though I love being in a supermarket. So wait a minute. I love supermarkets. I love to look at all the packaging. To me, that’s a little bit like a museum. But that’s a digression. I think that we have the opportunity to understand silence around us, and really looking, all the time. There’s always the opportunity. And there’s never a lack of things to look at, and there’s never a lack of time not to talk.

Ms. Tippett: Museums are just among the very few silent places in culture, where that is part of the element of the experience. It’s actually very unusual. I guess when we go to a concert — I guess there are places we listen. But there’s not…

Ms. Kalman: Right, it’s different than looking at something and not talking and absorbing it in that way. If you approach it the right way and don’t trudge through too many things that you can’t stand, it really gives you a sense of inspiration and clarity in your life.

Ms. Tippett: I spoke to Ann Hamilton a couple of years ago, and she used this phrase: “alone, together.” I think that’s the other thing. It’s different from being at a concert or a performance, where you’re having a communal, collective experience, because it’s both in a museum. You’re having a very personal meander, and what you’re paying attention to, you’re choosing. And yet you are not alone.

Ms. Kalman: I spend Fridays at the Met for two reasons: One, because I have an exhibit at the Met, an installation with my son, which is a recreation of my mother’s closet. It’s in the American wing, and it’s a wonderful — my mother only wore white, and she was very precise about her clothing and about her closet. And her closet really was a work of art, in its way. So it’s now at the Met, I’m happy to say.

Ms. Tippett: So your mother’s closet — I guess even when you said that the supermarket for you is like a museum, that you’re looking at the packaging, and I think of, also, the way you talk about being in the park, and you also take great delight in clothing, hats, shoes, and not in the way we tend to think about those things in terms of fashion, but in terms of how interesting humans are, [laughs] how interesting life is.

Ms. Kalman: I’m so curious about so many things that I surprise myself with my curiosity and my desire, my delight in seeing all of this stuff, because at a certain point, you’d say, “O.K., enough already.” But clearly, it’s never enough. It’s a surprise. You just don’t know what you’re going to see. And the fact that I can use that surprise in my work, the fact that I can not know what the painting that I have to do tomorrow will include, for an assignment that I know what the assignment is, but I don’t know what woman wearing what dress walking what dog, if that’s the case, or some person is playing the violin on the street, how they enter the work. And I think that the immediacy of my emotions is felt in the drawings.

Ms. Tippett: I want to talk a little bit about The Principles of Uncertainty, which — to continue on the philosophical, meditative side of you, [laughs] which is also whimsical. It’s interesting — your mother comes in again, your mother’s map of the world. Obviously, people who are just listening to us talk won’t have that picture in front of them, but talk about what is there and why that is so important for you. That’s an important touch point for you, that map.

Ms. Kalman: I have to say that the map, for those listeners who are inclined, I’ve spoken of it so many times that it must be online. If you go to “Sara Berman’s map of the United States,” or something like that, you might find it. But when I was doing the next year’s piece — the year that I did about American history, “And the Pursuit of Happiness” for The New York Times, after my year of introspection — they sent me to all kinds of places, and I asked many people to draw a map of the United States from memory, just sit down and do it. And as I say, it’s a complicated country with lots of different sections, and I don’t think most people would get it 100 percent right.

But my mother sat down and made an egg-shaped circle and Canada on top. So far, so good, but then she has California and Hawaii underneath Canada. She has — everything is completely topsy-turvy. She has Lenin, the village she came from, and Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and she has a few random places that are incomprehensible. And then, through the center, she says: “Sorry, the rest unknown. Thank you.” I have a huge version of that on my wall to remind me that it’s not about — I always say, “It’s not about getting it right, it’s just about getting it.” And that’s a big, big difference. If you have the freedom to use your imagination and to really express what you’re thinking, you’re going to come up with something a lot different than a correct version of the United States of America — or anything.

Ms. Tippett: It’s also evocative right now, in a way that you wouldn’t have foreseen previously, but this fact that we, all of us, all around, in all of our differences, seem to be operating with different maps of the places that we know and the places that matter. That’s a real phenomenon right now, these maps in our heads.

Ms. Kalman: The maps in our heads. Of course, then I think about the “New Yorkistan” map that I did with Rick Meyerowitz for The New Yorker after 9/11, and I think that with the conversations that people have about who are the tribes? Who do you belong to? Who do you belong with? Do you want to belong? Are there all kinds of new tribes now that we never understood or knew about? And really to find out, who do you love? And who do you want to be with? You’re forced to say, who do I relate to? And who do I respect? That’s a really big question. And who am I afraid of?

Ms. Tippett: It would almost be a really fascinating civic activity for you to ask Americans to do their map, to have your mother’s map as the prototype and say, “Create your own.”

Ms. Kalman: That’s a good idea.

Ms. Tippett: It would be, right now, fascinating. The Pursuit of Happiness book, as you said, also came out of it. You went to all these places, right? You met with all kinds of different public servants, and you went to the Capitol and farms and Mount Vernon and the White House.

Ms. Kalman: I went to the inauguration. I met Ruth Bader Ginsburg. I went to an Army base. All the places that I wouldn’t have access to as a normal person, The New York Times was able to send me to all of these places.

Ms. Tippett: How did that surprise you, how did that change you, that experience?

Ms. Kalman: It changed me profoundly. I really knew very little about American history. The more I traveled and the more I read and the more I met people, the more extraordinary the history of the United States — it was clear that this country was founded, by some miracle chance, of geniuses and that they were able to form an idea of a place.

Ms. Tippett: This was 2010, we should say, or the book was published in 2010.

Ms. Kalman: Actually, I did the traveling — I started 2008, with the inauguration of Obama and went to Monticello and did a piece about Lincoln and did a piece about Jefferson and really had a chance — still superficial, obviously — to admire the United States so much more than I ever had, with all the complexity, with all of the horrible parts, which exist for every country. And I had a lot of fun thinking about all the good things that go on here.

Ms. Tippett: It’s a beautiful celebration. I say that, and that can sound like a coffee table book, and it’s not. It has that whimsy. It has that quirkiness. It has this constant interaction that is there in real life between play and what’s interesting and fun and also hard and sad.

There’s a part — again, I meant to bring this, but it’s O.K., because nobody who’s listening to us is going to have the pictures in front of them either — you were at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the 101st Airborne Division. The way you wrote about those soldiers and that place — say a little bit about that, about what you saw. That was very moving to me.

Ms. Kalman: The thing that happens when you meet people is that all generalizations fly out the window. And you realize that people are leading very particular and very complex lives and that you can’t just make blanket statements. “This group does this, and that group does that.” It’s just immensely complicated. Every human being is a human being. So people who you might think you have absolutely nothing in common with philosophically or just on a daily level, you find out that there’s a tremendous amount of contact.

It might be so obvious to say that, but I don’t think that you can appreciate that until you actually go and live that. So the more often that you can, it reduces a kind of arrogance or a kind of superiority, like, “Oh, I know the right way, and you obviously don’t” to, “Clearly, we have different ways of looking at things, but we really can have a conversation about it and find the common humanity.” That’s what that taught me in a really wonderful way.

Ms. Tippett: The 101st Airborne Division was getting ready to go to the battlefield — I think to Iraq and Afghanistan — and so they were doing serious business. But you talk about how each one of them is so amazing. Each one of them breaks your heart — just the humanity. And then there’s a picture of a piece of cherry pie. [laughs] Do you remember this, from the base?

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] Yes, of course. I’m always looking out for a good pie and a good painting of a pie. It’s those moments — of course, the smaller moments diffuse the bigger ones. And also, they’re really important. So how do you sit together over a cherry pie? And it wasn’t that great, but it was good to have.

Ms. Tippett: It looked delicious in the picture.

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, the picture was better than the… [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Irresistible. I think you said something like, “Great solace is provided in the base by the piece of cherry pie.” [laughs]

Ms. Kalman: Yes.

[music: “Riddle Me This” by Rhian Sheehan]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the visual storyteller Maira Kalman.

Ms. Tippett: I feel like Lincoln is really important to you, too — Abraham Lincoln.

Ms. Kalman: I love Lincoln. [laughs] I’m in love with Lincoln.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] And how did that happen? Has that been a longtime love?

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] And he doesn’t know. I haven’t said a word to him. It started — I was asked by a library in Philadelphia to do a piece about Lincoln. So I went to their archive, and I was looking at the work. And I have books of photographs of Lincoln. Of course, he is the iconic — the first president to be photographed, and also just this extraordinarily beautiful, humanitarian man of kindness and wit — a poet. The more I read about him, the more I understood that he did have a sense of humor and that he also was completely brilliant. I thought, I really had a big crush on him, and I was a little bit annoyed that he was with Mary Todd Lincoln. And I wasn’t registering the glitch of the time thing. I just was like, “I really should be with him.” And who doesn’t fall in love with Lincoln? You spend five minutes reading about him or looking at his face, and it’s really hard not to fall in love with this man.

Ms. Tippett: I did notice that you noted that his stepmother loved him madly and let him be free to daydream. And I feel like you saw your own mother, and the way she let you be free to daydream, in that.

Ms. Kalman: That’s true, the connection. But they make a lot of it in the history books, that she really was somebody very unusual. And he wasn’t so keen on doing chores, the way all the other boys were, and he was more interested in reading Shakespeare, which is extremely unusual. He only had a year of formal schooling. So for somebody to be kind and love you for that, that’s critical.

Ms. Tippett: And also, I think we know this, that he’s a good example of that — you said he has a sense of humor. He’s kind of this glorious human being and also somebody who had great sadness and struggled with depression.

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, Jefferson had severe migraine attacks, which come from stress and sadness, also; I mean other things, maybe. I can’t imagine a human being, any human being, that doesn’t have attacks of depression. So clearly, somebody who’s living his life, losing his children, being in the war — the list could go on. How could he not be depressed? There’d have to be something wrong with him if he didn’t go into depressions. And then, of course, he only lived four days after the end of the Civil War, which is an extraordinarily sad fact for him and for the country and for history.

Ms. Tippett: This is kind of going back to the walks you take in the morning. Something you write about is that you have a specialty of following old people who have trouble walking.

Ms. Kalman: Yes, and I really try to walk like them.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me about that.

Ms. Kalman: I’m co-creating a ballet now with a wonderful choreographer called John Heginbotham. He’s doing the choreography, but a lot of the time, I’m very sensitive to the fact that — I’m doing the visuals, but I’m also in it, which, I guess, constitutes being an older person in a ballet. So the way that we move through space is really interesting to me, and I am conscious of the fact that we are moving and dancing, in our way, all day long. It’s funny because Nietzsche — if I can quote Nietzsche — said that a day that doesn’t have a dance in it is a lost day, which you wouldn’t expect from somebody like Nietzsche, who was crazy.

Ms. Tippett: No, and intense. [laughs]

Ms. Kalman: And intense, and had such a giant mustache, as I write about. But I never — when I saw that quote, I said, “This is incomprehensible.” But the fact is that we really are all moving and dancing, all day long. The older you get, the more challenging it is, obviously, and the more dangerous it is. And you can trip. I tripped on the sidewalk and broke my arm, and I thought, “Well, how did this happen? This is absurd.” So my heart goes out to everybody — that’s it. My heart goes out to everybody.

Ms. Tippett: You wrote — these are beautiful words, I think, and this is from Principles of Uncertainty, I’m pretty sure: “How are we all so brave as to take step after step? Day after day? How are we so optimistic, so careful not to trip and yet do trip, and then get up and say, O.K. Why do I feel so sorry for everyone and so proud?”

Ms. Kalman: That’s a good question. Why? [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: You mentioned aging, and I wanted to ask you about that, because it feels to me like you accomplished, earlier — or you held onto something that I think we mostly do when we’re kids and then many of us learn to do again as we get older, which is just to slow down, look around, appreciate, challenge the idea that there’s any reason to be in a hurry. But I feel like you held onto that across your lifespan, rather than letting it go for the middle years and then coming back to it, relearning it.

Ms. Kalman: It’s incomprehensible how that happened, but I did. I hear that from people. It’s not something that I don’t hear. Somehow, I have retained the sense of wonder about the world and the sense of beauty and preciousness of our time. Sometimes I’m stumbling about, not thinking very much, and I have never tried to be that way. I guess that’s how I am.

Ms. Tippett: Do you think that also grew out of — that you were emboldened or quick to do that because of your mother, and somehow, the way that your childhood worked or just also, I guess, how you’re constituted?

Ms. Kalman: Separating the threads is something that I can’t do because you’re born a certain way with a certain temperament, and then the fates allow this temperament to flourish or not, depending on luck. So I was lucky.

Ms. Tippett: But I do feel like it’s possible to learn this, and I think your work — your pictures, your books, your writing — are little encouragements. [laughs]

Ms. Kalman: Right, but then I get annoyed at being so encouraging, and I say, “Wait. I have black moods too. Don’t be so encouraged. It’s not so good.” So I get a little bit contrarian.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] I know what you’re saying. That sounds kind of cheesy and romantic and optimistic, to be encouraging. But it’s not. It’s complex.

Ms. Kalman: Right. And I shouldn’t be embarrassed or ashamed of seeming to be optimistic or encouraging, because really, it’s O.K. I say, “It’s O.K. It’s fine.”

Ms. Tippett: It may be unfashionable, but it may also be necessary. [laughs]

Ms. Kalman: Yeah, it’s O.K.

Ms. Tippett: This is kind of an enormous question, but I want to know where you would start walking into it, how your sense of this question of what it means to be human — how your sense of that is evolving now, at this point in your life.

Ms. Kalman: I joke about not knowing, but I think that as people get older, they tend to say, more clearly, “I really don’t know anything.” And of course, that isn’t completely true, but the only thing that I’m left with is, really, who do you love, and what do you love to do? I think that in the end we’re left with this sense of not knowing and striving to find the most-true place that you have in this lifetime, with people and with work. I don’t know what else there is.

Ms. Tippett: And this idea — these are your words, but that the subject of your work continues to be “the normal, daily things that people fall in love with.” That’s very resonant with that. I’m just curious — we’re talking in the early afternoon. Have you fallen in love with something today?

Ms. Kalman: Oh, yes.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Tell us, what have you fallen in love with?

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] Too many things.

Ms. Tippett: O.K., just start.

Ms. Kalman: I’ve been painting all day, and I’ve been doing paintings for this book about cakes, this cookbook. I’m doing paintings and short stories and memories of cake. And there’s a page about meringue. The cookbook author wrote about meringue. And I found this fantastic photograph of an Eastern European bed that has a huge quilt with a huge scalloped edge, and it’s all fluffy and white, and it looks just like a meringue. So I’m doing a painting of that bed as the illustration for meringues. So I’ve fallen in love with that.

And there was a photograph in The Times today of dancers, and I cut out a lot of photographs of people dancing, and I know I’m going to paint them too. I’m sure when I leave here, and I walk downtown — I’m going to walk home to 12th Street — there’ll be many, many things that will enchant me and make me very happy.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] This has been really delightful. I notice that you said that in your family you don’t say goodbye, you say, “So long.” Why is that?

Ms. Kalman: [laughs] I don’t know, because “So long” sounds a lot sadder than “Goodbye,” so I don’t know why. It’s something that my mother started, and I’m afraid to change it.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Your mother again. We began with your mother, and we end with your mother.

Ms. Kalman: Everything; it’s all connected to her. Sara said, “So long,” so that’s what I do.

Ms. Tippett: All right, well, I’m going to say “So long” to you, and thank you so much. What a pleasure it’s been.

Ms. Kalman: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure for me too. Thank you, Krista.

[music: “for all the forgotten resolutions” by Lullatone]

Ms. Tippett: Maira Kalman is the author and illustrator of over 20 books for adults and children. She’s a regular contributor to The New Yorker magazine. She continues to work on ballets with the choreographer John Heginbotham. After she left the studio at the end of this conversation, Maira sent me the following email: “You asked what I might fall in love with after our conversation was over. I took off my headphones and walked out of the room and saw these green chairs, which I immediately fell in love with, photographed, and will certainly paint sometime soon. The eternal pleasure of chance encounters.”

Staff: On Being is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Casper ter Kuile, Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, Zach Rose, and Serri Graslie.

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing our final credits in each show is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.