Mohammed Fairouz

The World in Counterpoint

He’s been called a post-millennial Schubert. Mohammed Fairouz has composed four symphonies and an opera while still in his 20s. He invokes John F. Kennedy and Anwar Sadat, Seamus Heaney and Yehuda Amichai in his compositions. He sees “illustrious language” as a form of music — and as a way, just maybe, to shift the world on its axis.

Guest

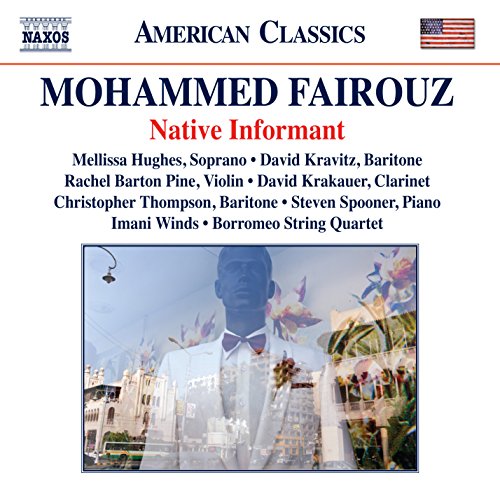

Mohammed Fairouz is a composer whose opera and symphonies have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and The Kennedy Center. His 11 albums include Native Informant, In The Shadow of No Towers, Poems and Prayers, and, most recently, Follow, Poet.

Transcript

April 30, 2015

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY: When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the area of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.

[music: “Audenesque: I.” by Mohammed Fairouz performed by Kate Lindsey]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: This is how Follow, Poet, the new album by the composer Mohammed Fairouz, begins. He’s been called a “post-millennial Schubert.” He’s composed four symphonies and an opera while still in his 20s. And he’s as passionate about statecraft as about art, so he invokes John F. Kennedy and Anwar Sadat, Seamus Heaney, and Yehuda Amichai in his compositions. He weaves poetry, even enduring political speech, into his music as a form of music too — and a way, just maybe, to shift the world on its axis.

MOHAMMED FAIROUZ: I think that music and poetry, the arts, do something that is very, very special in that they allow us access to a rarefied space, a sacred space almost. They take us beyond the 9/11s, beyond the Tahrir Squares, beyond Facebook and Twitter and all of this stuff. They allow us to reach beyond the day to day. They allow us to reach beyond the muddled present and in a way to touch something that is timeless and eternal.

[music: “Audenesque: I.” by Mohammed Fairouz performed by Kate Lindsey]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. With Follow, Poet, Mohammed Fairouz is the youngest composer to record a full album for the august century-old Deutsche Grammophon label. Among his many commissions, he’s written pieces for Borromeo String Quartet, Imani Winds, and the violinist Rachel Barton Pine. Mohammed Fairouz, who is first-generation Arab-American, was born in New York City in 1985.

MS. TIPPETT: I read somewhere that you were — you began composing music at a very early age. And I read somewhere that you were setting the poetry of Oscar Wilde to music at the age of 7. Is that right? I…

MR. FAIROUZ: Yeah. It’s a song on a poem by Oscar Wilde that is called “The True Knowledge.” And it’s a beautiful poem. I took a stab at it when I was 7. And I have to admit, I didn’t understand the poem at all. But I gave another go at sort of trying to revive it. I revisited it in, I think, 2002 or something as an early piece and tried to fix it. And I’ve since stopped doing that because I realized that as a composer, we leave very important traces of who we are spiritually in the pieces that we compose. And so it’s actually best not to tamper with who you were ten years ago to be who you are today. Accept and perhaps even try to love who you were ten years ago. And be kind to yourself. But also look forward to who you want to be in a year.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s lovely. I wonder if — I asked you if you — it seems like you began composing at an early age. And you were also always — and you’ve used this language of being obsessed with text. And I just wonder, how do you — where do you trace the kind of source or spark of these intertwined passions for you in the background of your life, in your early life?

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that one has to be obsessed with text in order to take it seriously. I mean, obsession is such a healthy thing. And for a composer, for an artist, for a human being, for a poet, for a diplomat, being obsessed with something is absolutely essential to getting what you want to get done done. And I guess I should say something about that because whenever I look back at innovative personalities, whether it’s Mozart or Steve Jobs or Shakespeare or Benazir Bhutto — whoever it is, they always seem to have that very — when you’re reading about them, when you watch them speak, when you listen to their music, whatever, when you read their speeches, you always register a sort of obsession. There’s something obsessive about what they’re committed to. And I think it makes for an extraordinary — at least an extraordinary commitment in what you’re doing. So being obsessed with text, Krista, is about diving into the text, accepting the text, opening your emotional pores to the text, and not simply treating the text as a dead, intellectual document. You’re also, in a way, accepting it as part of your life.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. FAIROUZ: And that may be something as old as Dryden or Shakespeare or as new as Mohammed Hanif. It’s imperative to be obsessed.

MS. TIPPETT: And was there a spiritual background to your childhood that also reinforced or kind of helped plant your love of text? And just — there’s such a — there’s this poetic, aesthetic sensibility, kind of a fulsome, well-rounded complete sensibility that’s there in your work that I actually also find very much in the fabric of Islamic culture, these winsome things like connections between spiritual life and love poetry. Or even you’ve talked about that calligraphy — that for you, there’s kind of a resonance between this treasured art of calligraphy when you’re writing musical notation. Do you know I’m saying? I feel like you kind of embody this aesthetic sensibility that’s not so well known about Islam.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I’m — yeah. I’m very saddened that it’s not so well known because, in a way, the Qur’an itself literally translates as “The Recitation,” “The Reading.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. FAIROUZ: And that is not so far away from the idea of “The Recital,” “The Musical Recital,” “The Poetic Recitation.” What’s extraordinary about poetic recitation, whether it’s happening in a very public setting like a poetry reading or a very private setting like your living room, is that when you sit down and you recite poetry, time stops. Something very special is understood to be happening. And people accept that, and they listen. And if you go on the streets of Damascus or Cairo or Beirut, or at least when I was there, people would read poetry in the cafes at night, recite poetry.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. FAIROUZ: Not even read it but recite it from — as that beautiful expression has it — by heart, from memory. And other people responding to the poetry would weep. They would cry. They would lose it. Nowadays, about an hour outside of Karachi in Pakistan, the fakirs still come, and they sing old Sindhi legends, old Sufi legends. People come and they take it in. And you see people in the audience absolutely losing it and opening up the emotional pores, becoming more vulnerable. And I think there is a mysticism. And there is a great part of Islamic culture that is maybe not perceived. But you know, Krista, peace never makes headlines.

[music: “Sadat: July 23rd, 1952” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Evan Rogister & Ensemble LPR]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with the composer Mohammed Fairouz. His new album, Follow, Poet, includes a song cycle, “Audenesque”, setting verse by W.H. Auden and Seamus Heaney; and a five-part ballet called “Sadat”, instrumentally telling the life story of the late Egyptian President. This is the first movement from “Sadat.”

[music: “Sadat: July 23rd, 1952” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Evan Rogister & Ensemble LPR]

MS. TIPPETT: I’d like to talk about your album Follow, Poet. I think in Follow, Poet, this latest album, you’ve brought into relief — you’ve really worked with and played with, really, this passion that you have for the interplay — and I’m not even sure this is going to be precise, as I say it — but between text and music. And it’s so striking. You start — the CD actually starts with a speech of John F. Kennedy, a speech that — I don’t know that it’s — how famous it is. He was receiving an honorary degree at Amherst College in 1963 — October 26, 1963, which would have been shortly before his death.

MR. FAIROUZ: Yes, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And you wrote of this speech, “The speech is a kind of music by itself.” You’ve said that you’ve been challenged for people asking you, “Why can’t you just write music for the sake of writing music?” [laughs] And I want to just draw you out on and how you respond to that and how you think about what you do that’s different, that is resisting that, right, just for the sake of music alone.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I mean, Follow, Poet as an album is something I’m very, very proud of. And it’s the accomplishment of many, many people who put their blood and sweat and tears and intellectual energy and acuity into creating something that I think is meaningful. When we talk about the interplay of text and music, we often talk about poetry and music — what comes first? The music or the text? This is an old question that is asked in sort of the forums of academic minutia. But, actually, text is so much bigger than that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. We’re also often talking about lyrics, right? And that’s quite different from what you’re talking about.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, absolutely. I mean, historically, if you look at the sort of 19th century art songs, what we call lieder — lieder can be understood as sort of 19th century versions of Beatles songs, right?

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. FAIROUZ: They’re — all the little lyrics of these lieder, hundreds and hundreds and thousands of lieders, are all just sort of poems. So these, I mean, I’m sure that when we talk about the classics now or in fifty years from now, whatever, we’re going to see the lyrics as poetry. I mean, the Beatles lyrics are poetry.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right, right.

MR. FAIROUZ: Freddie Mercury’s lyrics are poetry, absolutely. And actually, if you write them down, you recite them, you study them, I mean, they become — and some poems become indelibly linked forever and married to the music that they’re created with. And then they become lyrics. But in any case, I think that we expanded the idea of text. I mean, the idea of text in music often is lyrics, poetry. You’re absolutely right. But text can be a speech given by a political leader. A text can be a road sign, for goodness sakes. It can be anything. I mean, text can be anything, and it can acquire tremendous meaning. And goodness knows, I mean, if you’re traveling in the Middle East, there are road signs that are poetic in their weight and their heaviness, their meaning to people.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean?

MR. FAIROUZ: They’re emotional.

MS. TIPPETT: What would an example be?

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that a road sign leading to the Old City of Jerusalem has a lot of semblance, a lot of meaning — a sign outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I mean, Mahmoud Darwish and Yehuda Amichai wrote two poems that are separate from one another, developed separately.

MS. TIPPETT: And they are Palestinian and Israeli.

MR. FAIROUZ: Palestinian and Israeli poems writing simultaneously about the same place and using the phrase, “Every rock is sacred, every stone is sacred.” And of course, that brings up semblance of the Psalms and that every one of your stones is sacred. So actually, a stone can contain within it, a rock can contain within it poetry.

[[music: “Symphony No. 3, “Poems and Prayers — Oseh Shalom” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by by Sasha Cooke, David Kravitz; Neal Stulberg: University Of California Philharmonia, UCLA Chorale]

MR. FAIROUZ: And so we started to sort of go back and forth about the idea of how to interweave text and music. And I think that starting with John F. Kennedy’s address at Amherst College, which is absolutely musical, in it he says — he talks about the role of the artist. He says, “Where power corrupts, poetry cleanses” — the idea of poetry as a cleanser.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FAIROUZ: He actually concludes in the end that he sees a little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than the full recognition of the role of the artist. I think it’s absolutely not coincidental as an aside that this is the same president who said let’s put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. And we decided to do that and then go from there to the music and come back to his voice and have only — also a musical evocation of another political speech half a world away by Anwar Sadat. And that’s the great speech that he delivered when he made, in the Arabic tradition, in Arabic history, we know it as the longest journey that Anwar Sadat ever took in his life. The well-traveled diplomat and politician, one of the most seasoned statesmen in the world, who traveled all over the world thousands of miles — we think that the longest journey he ever took was that 28-minute journey from Cairo to Jerusalem…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. FAIROUZ: …to deliver that speech to the Israeli Knesset.

[music: “Sadat: Jerusalem” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Evan Rogister & Ensemble LPR]

MS. TIPPETT: So, Anwar Sadat, president of Egypt — he was assassinated in 1981, before you were born.

MR. FAIROUZ: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I think what’s interesting about Sadat, who many people of your generation won’t remember and might not even know about — and perhaps in the immediate history following his death, appeared a tragic figure — it’s very intriguing to me that, for you, he’s kind of a guiding light. And I see Sadat’s legacy having this living resonance in your work. I mean, here’s some language from that speech to the Israeli Knesset, which I had never heard before: “Fill the earth and space with recitals of peace. Turn the song into reality that blossoms and lives.” And what a reflection that is of, again, this approach you’ve taken to the interplay between text and music. There’s music in his words somehow.

MR. FAIROUZ: Absolutely right. These figures, who appear to the people of their generation as tragic figures, become guiding lights to the people of the next generations and the generations to come. And you know, Krista, it absolutely proves the violence that some people espouse, the violence that some people believe is the solution doesn’t work. It’s absolute proof of the fact that this violence simply does not work. John F. Kennedy’s words that open Follow, Poet — his voice is one of the most recognizable voices in the history of the 20th century.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. FAIROUZ: It’s really interesting to note that the people who attempted to silence him, the minority of people — I mean, he had a nation behind him. He had the support of much of the world. And yet, there were a few people who decided that violence was the way to silence him, I mean, that he must be assassinated. And those people who attempted to make that point are forgotten. I don’t — I would not recognize their voice if I heard it on an album. And yet, John F. Kennedy’s voice still resonates. And then of course it drives the point home that this is a minority of people. I mean, Sadat — it took, what, five, six people who eventually end up to be associated with al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood who wanted to silence him by assassinating him at the military parade. And yet, his voice becomes the guiding light, as you say, for a new generation of people who believe in peace.

[music: “Sadat: Jehan” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Evan Rogister & Ensemble LPR]

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you often reflect on yourself as a member of your generation. Somewhere I saw you’re referred to as a post-millennial Schubert.

MR. FAIROUZ: [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: I didn’t realize — but I was more — the Schubert part I get. I didn’t realize that we’d moved to post-millennial.

MR. FAIROUZ: Me neither.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m not sure what all these labels mean. But there is something about a turn of century generation of which you are part. And what you’re describing now about this suspicion of the rush to results, a new kind of openness to language that makes something new possible which — a language that reorients. I feel like that’s what you’re describing. Do you feel like that’s a gener — sorry. What were you going to say?

MR. FAIROUZ: I’m going to say something that you may think me crazy to say. But I believe that the future is extremely bright. I believe that the future is hopeful. And I think that this generation is absolutely committed to making the world a better place. And I think they have the means to do it. And I think that if the world does not become a better place by the time that I’m 50 or 60, we have no one to blame but ourselves. We have the will. We have the drive.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FAIROUZ: We have the knowledge of the world at our fingertips. I think the resources available to us are unparalleled. And light the way to, I think, a great future.

MS. TIPPETT: I have to say that I share your confidence and hope in this generation. But I think something that’s also characteristic of what is most hopeful now is also reflected in you. I mean, yes, you have this 21st century world of perspective and tools. But you’re also very attentive to, as you say, guiding lights. Right? You know, looking back for wisdom as well, looking for prophetic, poetic voices, taking elders seriously. I really see this in the way you lift up John F. Kennedy or Anwar Sadat or Seamus Heaney, Yeats. That I feel is part of the power that your generation is claiming as well. Do you know what I’m talking about?

MR. FAIROUZ: I do think I know what you’re talking about. I think that — I think we have a long way to go with that. And I think that lifting the elders is an important element of any successful tribal society. And all human society is tribal. We are all tribal creatures by nature. And I hope that we get there. I think we have a ways to go.

[music: “Sonata for Solo Violin, ‘Native Informant’: II. Rounds” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Rachel Barton Pine]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Mohammed Fairouz through our website, onbeing.org. I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Piano Miniatures: III” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Lydian String Quartet]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with the composer Mohammed Fairouz, who’s been celebrated as a Schubert for the post-millennial generation. This is “Piano Miniature III” from his 2011 album, Critical Models.

[music: “Piano Miniatures: III” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Lydian String Quartet]

MS. TIPPETT: In his life and his music, and especially in his new album, Follow, Poet, Mohammed Fairouz makes unexpected connections between music and speech, between art and statecraft. He opens the notions of illustrious language and classical music for a transforming world.

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s something really beautiful that you wrote: “Music has accompanied humanity from the very start of our journey, and it has been intertwined with human society ever since. The idea of separating music from the aspirations of society is artificial to me. Beyond the basic utilitarian uses for music in our cultures, to march off to war, sing when the crops are brought in, serenade one’s loved ones, rock a child to sleep with a lullaby. There is an inherent storytelling aspect to music that is linked to the past and the future of every society.”

MR. FAIROUZ: Absolutely. I think that the concept of music for the sake of music or art for the sake of art is not only a new concept, I think it’s also a pretentious concept. I mean, when people ask me, “Why don’t you just write music for the sake of music?” My response is not only that it’s uninteresting to me but my response is also that music has accompanied human civilization. It’s been an essential storytelling element that keeps, again, the tribe alive, keeps the identity of the tribe alive. Music and poetry are inextricably linked to our humanity. And so I’m not interested in separating music from that just to aggrandize my own cleverness or whatever as a composer. I think I need to be communicating with people. I need to be talking to people. I need to be moving people. The days of classical music are over. The days of elitism in art are over. The days where artists speak over people’s heads and then claim that they’re more clever and more special than the people who don’t understand what we’re saying are over. You have to speak to your audience.

MS. TIPPETT: Isn’t it interesting — and I’m going to say this as an “and” rather than a “but” — Follow, Poet is — with this album, you’ve become the youngest composer to record a full album for Deutsche Grammophon, which is this iconic 115-year-old classical label. I mean, I think that speaks to evolution.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that — I think it speaks to a faith in the young.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FAIROUZ: I think it speaks to, hopefully, what’s being said in the music. And I think, as I said, I mean, this album is the result of the work of many, many people, who all sort of unified their vision and believe in something, I mean, believe in something that’s bigger than themselves. We believe in something that’s bigger than ourself. It’s believing — we all believe that someone who listens to this may be moved. It may affect them. It may move them to do something good in their day or in their hour or in their life. I mean, maybe that’s too much to hope for, but if it’s a very small percentage of people, it’s still better than sitting around and doing nothing.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve spoken of the artist as an agent of hope, which I hear in what you just described. Again, to that question, to that eternal, that cynical question that always arises, to what effect? What difference does it make? Does it change the world?

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that’s a very interesting question, actually. And I think that it is a question that’s viable. What’s the point? What’s the use of poetry? What’s the use of art? And Auden actually asks that question. I mean in the elegy for Yeats, which is set to music in my song cycle, “Audenesque,” on this album, Follow, Poet.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Do you have those lines — do you have that in front of you? That “Follow, Poet, follow right to the bottom of the night…”

MR. FAIROUZ: You know, absolutely not. I don’t have the lines in front of me, but I carry the lines everywhere I go. I think that — I carry them in my head.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FAIROUZ: I have to say, I think memorizing poetry is absolutely vital. It’s absolutely important. It gives the poetic tools that one needs to get through life.

MS. TIPPETT: Can you just say some of that?

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that what’s extraordinary about the elegy for Yeats is that it begins in a very cynical and dark place. “He disappeared in the dead of winter: The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted.” It gets darker and darker and darker. You have this image that could be contemporary Wall Street. “But in the importance and noise of to-morrow, When the brokers are roaring like beasts on the floor of the Bourse, And the poor have the sufferings to which they are fairly accustomed.” I mean, all of this stuff. And then he uses this line: “And each in the cell of himself is almost convinced of his freedom.” “Cell of himself,” “sequestered” — you know, being sequestered in the cell of yourself. And it gets more and more dark. In fact, then he asks the question, and says, “For poetry makes nothing happen.” He says this.

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Right.

MR. FAIROUZ: He says this in this poem. “For poetry makes nothing happen: it exists in the valley of its making where executives would never want to tamper.” And then it goes back to meter. It goes back to the poetry of the elders. “Earth, receive an honoured guest: William Yeats is laid to rest. Let the Irish vessel lie, Emptied of its poetry.”

[music: “Audenesque: III.” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Kate Lindsey]

MR. FAIROUZ: These are extraordinary lines that speak of the absolute darkness of Europe on the [inaudible] of going over the edge, the world on the brink of war. He says, “In the nightmare of the dark, All the dogs of Europe bark, And the living nations wait, Each sequestered in its hate.” Again, sequestration. Sequestered, each sequestered, each in his cell. But then at the very bottom of the night, Auden turns all of this around and says, “Follow, Poet, follow right, To the bottom of the night, With your unconstraining voice, Still persuade us to rejoice; With the farming of a verse, Make a vineyard of the curse, Sing of human unsuccess, In a rapture of distress.” And he goes on and on and on. It’s the most extraordinary thing, really. And I thought to myself, well, it’s a once in a lifetime poetic miracle.

[music: “Audenesque: III.” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Kate Lindsey]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with composer Mohammed Fairouz.

[music: “Audenesque: III.” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Kate Lindsey]

MS. TIPPETT: I would also like to talk about your Poems and Prayers album, your third symphony. And I always ask this question when I start, and I didn’t do it for some reason. Was there a religious or spiritual background to your childhood?

MR. FAIROUZ: You know, other than understanding Islam and having understood and in a way appreciating, now, my parents’ liberal view of Islam that so many people share, that the vast majority of Muslims share. It wasn’t anything that was absolutely central. But it was a part of my childhood for sure.

MS. TIPPETT: So when you wrote this symphony, this “Poems and Prayers,” you actually steeped in the poetry and statecraft of Israel as well as Palestine, I’d say, ancient and modern as you wrote this music. And I just — I’d be curious about what you’ve learned in that, how that may have changed you, imprinted the person and the composer you were after that.

MR. FAIROUZ: “Poems and Prayers” engages in the mess — it’s my third symphony — engages in the mess of the Middle East. And by mess, I mean it’s really about the fact that the Middle East, the Arab world, the history of the Middle East, the Assyrians, the Jews, the Phoenicians, the Israelites, the Philistines, the Egyptians, and so on and so forth is not a prix fixe meal. They all intermixed and intermingled. And in fact, it’s interesting when you look at this barbaric group ISIS. I like to call them Daesh because they don’t like that name, and that’s the Arabic acronym for…

MS. TIPPETT: And that’s what people call them, yes.

MR. FAIROUZ: And they actually went in and started an assault on the common heritage of all humanity, but especially of the Arab world, in destroying the Assyrian and Babylonian sites. But one of the things I was reminded of, when I was watching this terrible destruction take place was The epic of Gilgamesh. And reading in Gilgamesh, this idea the story of the man who created a great ark and who set sail as the world flooded under apocalyptic rising waters and saved the species, the varied species of the earth. And I was not reading the story of Noah; I was reading Gilgamesh. And this happened a thousand years — it was written a thousand years between — before the Old Testament story of Noah. So it’s interesting how all of the cultures in that part of the world intermingle and interweave. “Poems and Prayers” intermingles them in an interesting way. It starts with the Aramaic “Kaddish” — “Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash sh’mei raba” — which has acquired connotations of being the Jewish prayer for the dead.

[music: “Symphony No. 3, “Poems and Prayers” – I. Kaddish” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Sasha Cooke, David Kravitz; Neal Stulberg: University Of California Philharmonia, UCLA Chorale]

MR. FAIROUZ: But it also sets the poetry of Fadwa Tuqan. She was considered the poetess of Palestine, one of the greatest poets in Arabic literature.

[music: “Symphony No. 3, “Poems and Prayers” – III. Night Fantasy” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Sasha Cooke, David Kravitz; Neal Stulberg: University Of California Philharmonia, UCLA Chorale]

MR. FAIROUZ: And in fact, Arab schoolboys and schoolgirls throughout the latter part of the 20th century were required to memorize her poetry. And so…

MS. TIPPETT: Was this something that you knew before, or is it something you learned as you created this work?

MR. FAIROUZ: No, it was something I knew before.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. FAIROUZ: And also, the poetry of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. And then the great Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. FAIROUZ: And interestingly enough, all of the linguistic similarities come about as well, Fadwa Tuqan saying, “In this day,” “fi hatha al-yom” (في هذا اليوم), “yom” being an Arabic word for “day,” and Yehuda Amichai beginning “Memorial Day for the War Dead,” “yóm zikarón lemété hamilkhama” in Hebrew. The linguistic similarities, the similarities of theme, the similarities of culture, and then you go, of course, to that part of the world — the similarities of food, the similarities of expression, the similarities of — and you realize of course — I’ve said this before — that this is a family fight.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. FAIROUZ: And family fights, unfortunately — I mean, it’s — people say, “Well, why would you whitewash it by saying or undermine it by saying it’s a family fight?” Family fights are the most aggressive of all fights.

MS. TIPPETT: Are the hardest, yes. The most brutal, yes.

MR. FAIROUZ: We’ve all been through that. I mean, family fights are — we…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. I guess I also just want to point at what you’re describing which is immersing in — you use this language of statecraft which is kind of — which I like that. It’s kind of an old-fashioned term. It’s kind of a formal term.

MR. FAIROUZ: Oh is it?

MS. TIPPETT: But you are you are coming at all the things we talk about when we talk around statecraft by way of music and poetry and then making new — making fresh observations.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I mean — I think that statecraft is actually — I’m sorry to hear that it’s an old fashioned word.

MS. TIPPETT: It is a formal word, I guess I mean.

MR. FAIROUZ: I think it’s a wonderful word.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FAIROUZ: And I think that great statesmen use language in order to bring people together. I’m filled with a sort of poetic admiration, of course. And I think that it’s very, very interesting, actually, that the line between the arts and statecraft is not so as far away as you might think. The line between fiction and realism isn’t — I mean, that’s not a very expansive border. I mean, I’m now working on two operas with two different writers. And I was sort of meditating on this, and I found it extraordinary that both of them have a background in journalism. And both of them turned to fiction, turned to writing novels, because they found that they could tell the truth in fiction…

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Right, right.

MR. FAIROUZ: …more than they could in journalism. So it’s not a wide gap. It really is not a wide gap. I mean, sometimes truth is just truth.

[music: “Symphony No. 3, “Poems and Prayers – II. Lullaby” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Sasha Cooke, David Kravitz; Neal Stulberg: University Of California Philharmonia, UCLA Chorale]

MS. TIPPETT: You have drawn an interesting analogy between, let’s say, this frontier we’re on of living in a globalizing world and yet identity being as vital and essential a thing as ever before. In some ways, coming into relief. You wrote this: “One of my great mentors, Edward Said, borrowed the term ‘counterpoint’ from music and applied it to critical thought in politics and in society as a way for cultures to exist in a tapestry of counterpoint without any culture giving up its individual sense of beauty but contributing to the greater whole.” I mean, you often, in your music, use contrapuntal forms to multiple melodic lines that have their independence but make up one piece of music. I’m not sure if I’m saying that very eloquently. But it does seem to me a very useful analogy for where we are as societies as well.

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, absolutely. I mean, the world has to exist in counterpoint. I mean, in order to understand this, it’s very important to understand the musical concept of counterpoint. And the musical concept of counterpoint is very simple, actually. You have a melody or a tune. And it’s beautiful. And then you have another melody or a tune, and another one. And you put them all together and play them simultaneously, like singing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” in canon. And instead of each individual melody losing anything by being combined as a whole, it becomes like a wonderful tapestry, a tapestry where each of these individual threads doesn’t lose its meaning, doesn’t lose its identity, doesn’t lose its own raison d’etre, its own reason for being, but contributes to the whole tapestry of counterpoint.

[music: “Jebel Lebnon – Mar Charbel’s Dabkeh” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Imani Winds]

MR. FAIROUZ: So if we see the world as a tapestry of counterpoint, not hegemony of one line or one culture over another or domination or anything like that.

MS. TIPPETT: And also not necessarily harmonic or not always — right? Perhaps again and again harmonic but not continuously.

MR. FAIROUZ: No, because, I mean, imagine a piece of music of endless harmony. What could be more boring?

[music: “Jebel Lebnon – Mar Charbel’s Dabkeh” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Imani Winds]

MS. TIPPETT: I often will think at the end of a conversation like this about asking, through the life you’ve lived, through the work you’ve done, how has your sense evolved, how would you speak now about what it means to be human? You’re very — you have this keen awareness of the fact that we live in a post-9/11, post-Tahrir Square, globalized, technologized, 21st century world. What, for you, at this point in your life, would you say — what does it mean to be human and a musician at this moment in time?

MR. FAIROUZ: Well, I think that music and poetry, the arts, do something that is very, very special in that they allow us access to a rarefied space, a sacred space almost. They take us beyond the 9/11s, beyond the Tahrir Squares, beyond Facebook and Twitter and all of this stuff. They allow us to reach beyond the day to day. They allow us to reach beyond the muddled present and in a way to touch something that is timeless and eternal. And I think that is the essence of what we do, what we’re privileged to do as artists.

[music:“For Victims 1 – Prologue: The House Of Justice” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Borromeo String Quartet]

MS. TIPPETT: Mohammed Fairouz has recorded 11 albums including Native Informant, In The Shadow of No Towers, and Poems and Prayers. Follow, Poet is his latest work, and it’s the inaugural release in a new series called Return to Language by Universal Music Classics. And here’s how Follow, Poet ends, with the Irish poet Paul Muldoon reading the final lines of W.H. Auden’s poem “In Memory of W.B. Yeats.”

PAUL MULDOON: “Follow, Poet, follow right

To the bottom of the night,

With your unconstraining voice

Still persuade us to rejoice;

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.”

MS. TIPPETT: Listen again or share this episode at onbeing.org. On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Nicki Oster, Michelle Keeley, and Selena Carlson.

[music: “Sadat: July 23rd, 1952” by Mohammed Fairouz, performed by Evan Rogister & Ensemble LPR]

MS. TIPPETT: Our major funding partners are: the Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the frontlines of social change worldwide at Fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, fostering awareness of the power of love and forgiveness to transform our world. Find them at Fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, contributing to organizations that weave reverence, reciprocity, and resilience into the fabric of modern life.

And the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Our corporate sponsor is Mutual of America. Since 1945, Americans have turned to Mutual of America to help plan for their retirement and meet their long-term financial objectives. Mutual of America is committed to providing quality products and services to help you build and preserve assets for a financially secure future.

![Cover of Fairouz: Poems and Prayers [Blu-ray Audio]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61umM6DK%2BLL.jpg)