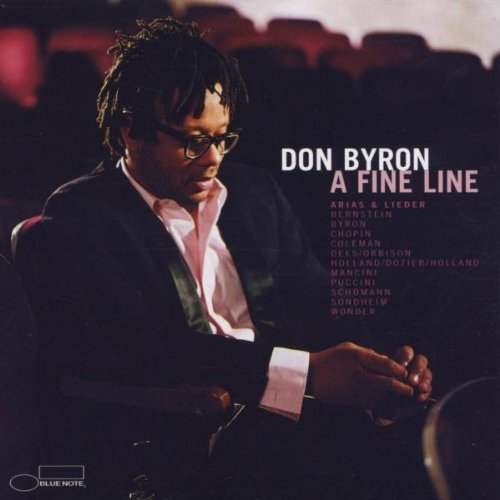

Nathan Dungan

Money and Moral Balance

The sales are starting, the stores are open late, and many of us are gearing up to spend more money than we actually have in a holiday season with deep roots in religion. We explore the turmoil many of us experience with money in our day-to-day lives — and how we might work towards a moral and practical balance for ourselves and the next generation.

Image by Rosley Majid / EyeEm/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Nathan Dungan is a financial educator and president of Share-Save-Spend, an organization that helps people develop healthy financial habits.

Transcript

November 8, 2007

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Money and Moral Balance.” The sales are on, the stores are open late, and many of us are spending more money than we actually have towards a holiday season with deep roots in religion.

MR. NATHAN DUNGAN: I believe the church has been complicit in sort of getting sucked into this whole persuasive argument about the role of consumerism in our culture, and I really don’t think they have understood the impact of what that means for people’s souls and what it robs us of in terms of just our personal sense of being.

MS. TIPPETT: This hour with financial educator Nathan Dungan, we’ll discuss the intersection of money and values in U.S. culture and in our families. Dungan offers practical tools for creating a counter-rhythm to consumer excess. This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Many Americans name greed and materialism as a moral values crisis. This unease unites us across other differences, but so too does the holiday shopping frenzy we’re about to enter. This hour we’ll talk about the conflict many of us experience between what we care about and how we spend our money. My guest, Nathan Dungan, is a financial educator with a philosophy and framework for bringing money into practical and moral balance in individual lives and in our families.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Money and Moral Balance.”

The root of the word “credit” is credo, to entrust or to believe, the same Latin root with which the great creeds of Christianity begin. A Protestant ethic of discipline about work and money shaped early U.S. culture and Western capitalism. But in our time, credit is something college students and even children have, and it is a lynchpin of debt. Few of us are immune entirely. At this time of year, many of us are torn between what we want to buy and what we can afford, between the pleasure of giving to those we love and the expectation that we must.

My guest, Nathan Dungan, began his working life in the financial services industry, but he had a turning point on September 11th, 2001. At the age of 36, he was already a vice-president of a religiously affiliated Fortune 500 financial services company. He was at a marketing conference in Lower Manhattan when hijacked planes struck the World Trade Center. Driving back home to Minnesota in a rental car, he was dismayed to hear the president give the country advice so normal in our culture: to move forward from this tragedy, in part, by going shopping.

MR. DUNGAN: To me, I just thought that there was this moment where we would have just a chance for some deep introspection, you know, about who are we, what are we about. And just immediately there was that sort of call to action, and the call to action was to head to the mall.

MS. TIPPETT: Today, Nathan Dungan is in demand in religious and commercial settings for his thoughts on living intentionally with money in a consumer culture. Advertising, he says, drives us into a cycle of seeing and wanting that focuses us on self and on immediate wants and needs. Dungan has developed a system for financial planning in families, which redirects attention to other values, giving equal weight to saving and sharing money as well as spending it. This creates what he calls a counter-rhythm to merely spending.

He doesn’t offer solutions as much as a framework for individuals and families to create their own new financial habits. In 2005, debt outpaced the personal savings rate for U.S. households for the first time since the Great Depression. And when I asked Nathan Dungan what he’s learned about such trends in historical and religious perspective, he points out that most of us can trace them in our own family history.

MR. DUNGAN: And I think this is very appropriate for your question because my grandparents, particularly on my mother’s side, farmers, eastern — southeastern Colorado, raising five children on a 70-acre farm, OK, vegetable farm, they had a very clear definition of needs and wants.

MS. TIPPETT: And the difference between needs and wants.

MR. DUNGAN: And the difference between needs and wants. They paid cash and they physically had to get in the car to drive into town, you know, to purchase items. And then my grandparents on the other side, I remember my dad telling me stories about in the Depression when he was very young, they had very little food in the house, but yet they still would invite neighbors over to share what they had because that’s just the way it was.

So here we are, there’s kind of the role of the church, I think, is sort of a guiding light in terms of needs of others and gratitude, and really understanding again what is your purpose and place for being on this earth. You know, I think you can’t argue that it’s a good thing that people perhaps have prospered and that more people are homeowners and those kinds of things, but it’s come at a bit of a price as well in terms of the amount of debt that we hold, and from a very young age. I mean, the amount of credit card and, you know, education debt that young people have today is just…

MS. TIPPETT: And I think that’s new.

MR. DUNGAN: It’s new and it’s…

MS. TIPPETT: In the last few years, it’s that college students have credit cards.

MR. DUNGAN: Absolutely. I mean, it’s new and it’s debilitating. And I think, in some respects, I believe the church has been complicit in sort of getting sucked into this whole persuasive argument about the role of consumerism in our culture, and I really don’t think they have understood the impact. I believe they are starting to get it, but I don’t think they have fully thought through the impact of what that means for people’s souls, for our, you know, sense of place and time and space, and what it robs of us in terms of just our personal sense of being.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that this was in an article you wrote. You asked a pretty condemning question, kind of the bumper sticker question, What would Jesus do?, but it was a version of that. What would Jesus say about churches’ complicity or even just complacence about turning the holiday that is Jesus’ birthday that we’re moving towards, turning that into this consumer fest?

MR. DUNGAN: Yes. Well, I think it was in the context, actually, of a sermon that I gave recently at Christ Church Cathedral down in Indianapolis.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, even though that sounds like a pretty obvious question, it’s not a question I’ve heard anyone ask quite so pointedly.

MR. DUNGAN: One of my goals is really to get people to stop and think about where we’re at. You know, there’s the great metaphor about the frog and the boiling pot of water, and that the heat just continues to get turned up but you can’t really tell that it’s getting warmer in the pot, right? The frog can’t. I think, to some degree, that’s our society around consumption. The heat has been turned up, but I don’t know that there’s been really a voice of kind of calling the question to say, ‘Is that acceptable; is that OK?’ And so when I put that phrase in the sermon, it was really a call-out to say, ‘Are we thinking about that?’ I mean, if Jesus were in the room today, I think He would be flummoxed by our obsession with consumption. And it doesn’t mean that we haven’t — aren’t still somewhat, to some degree, a generous people, but I do think there’s a point where that is going to be challenging for us to continue to follow through, to be generous when we’re so distracted by the time that we spend.

Jacob Needleman really, I think, focuses a lot on this issue in his book Money and the Meaning of Life, his whole notion about, you know, what is money about, what’s it for, what is the role that it plays in our life. And I think it was in some of his readings that I really started to ponder that.

Robert Wuthnow, a sociologist from Princeton, also asking many of these very same questions. I guess maybe what I’ve tried to do is put the question forth so that people on just a practical day-to-day level start to think about this intersection of money, values, and the culture, you know, and I ask people, are your values really reflected in the choices you’re making with money, or are those values being imposed on you?

MS. TIPPETT: Nathan Dungan. Here’s a reading from the book he just mentioned, philosopher Jacob Needleman’s Money and the Meaning of Life.

READER: “I remember a conversation about money that involved a businessman. ‘I was thinking,’ he said at one point, ‘it’s a real question for me. Is there a way of looking at money, of educating myself, and educating our children to look at money so that it is actually not dirty, so that it is a unifying factor in every scale, in every sense? Or is money only a problem? That, to me, is the question.’

“Several others present had been excoriating the rich as greedy and selfish, and condemning the American economic system for making wage slaves out of everyone, including teachers of young people, forcing them to sell out their ideals.

“Addressing the most vocal of these, the businessman broke in: ‘Could I probe you about that–because I am very moved by your concern for the materially poor people. Is it impossible that you would be concerned for the spiritually poor people who have a lot of money? Because if you could get some of them on your side, they might be able to help you accomplish what you have to do.'”

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. My guest, Nathan Dungan, says that what money means to us doesn’t find expression in stated values and ideals, but in habits, how we spend money moment to moment.

MS. TIPPETT: As you point out in so much of your work, we now have a generation of children who’ve been marketed to from the earliest days of their lives, and those of us who are parents and educators, I suppose we’ve been complicit, I mean, we’ve watched this happen, we’re — perhaps often being disturbed by it, but not having any idea how to counter it.

MR. DUNGAN: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: And not having the kind of commensurate tools to counter it. I don’t think my children — it’s so reflexive, you know. Their sensation of needing or wanting something and how those two things are merged are so instantaneous.

MR. DUNGAN: Right. It’s been — well, all the barriers have been obliterated, you know, so those real barriers of me needing to get in the car, like my grandparents did, drive to town, make a very conscientious decision — gone. Because now I have the need or the want thought, and I can literally scratch the itch, you know, instantaneously. If I’m sitting next to a computer, you know, or if I have, you know, a cell phone or some kind of gadget, I can literally scratch the itch. And I think some of that is about filling a void and it starts pretty innocently, I think, as children.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, I don’t know that in a five-year-old that there’s an emptiness, but does our culture create an emptiness by allowing that itch to be generated and then constantly scratched?

MR. DUNGAN: Sure. Well, I think it comes back to this notion of habits. You know, the credit card debt of a 20- and a 25-year-old doesn’t just sort of magically appear on the scene. It really starts in the form, I believe, of spending habits, five, eight, 10, 12 years of age, metastasizes into some, you know, deep credit card debt, deep consumer debt at a very early age, and so I think, to your point, I agree that it’s not like a five-year-old is sitting around saying, ‘Wow…

MS. TIPPETT: Having an existential crisis, right.

MR. DUNGAN: …I feel anxious because I don’t have…’ — you know, name the gadget or something. But compare the house that you grew up in with the house that your children perhaps grow up in today, or your bedroom. I mean, I shared a room with my brother until he went off to college and, you know, our big item in the room was a clock radio that my brother saved his money for. You know, and then today you look in the rooms of children, you know, and it’s just stunning to see the amount of things that they’re surrounded by.

MS. TIPPETT: Things. Yeah, things, things, things.

MR. DUNGAN: Things. And so again I would pose the question and say, you know, a five-year-old isn’t having this big existential thought about that. There is something … a comfort that’s created being surrounded by stuff, and then how does that ultimately take them as they move through adolescence and into adulthood? And then the concern that I have is how are they then distracted by their needs versus the needs of the world and the needs of others, the sense of gratitude.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. I think I’m aware in my children of something that is quite easy to buy into, which is, let’s say it’s a slow weekend or something just went right at school, there’s this urge, well, let’s — let me, let me buy a new action figure, and then that’s going to be the great event of the rest of the day and it’s going to be fun and, you know, action figures actually don’t cost very much for me.

MR. DUNGAN: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s kind of an easy way to create a good feeling and an activity, and yet I always feel bad about it, even when it does serve those purposes which I can’t quite write off as terrible. It’s a real bind.

MR. DUNGAN: Right. Right. I think that’s the big challenge. You know, the people often ask me — when I’m out speaking, they say, ‘But, yeah, if we follow your philosophy, won’t it tank the economy?’ And I say, ‘Well, redirecting money away from self and to some sort of future purpose or to help somebody else, you’re not really — it’s not like you’re burying the money under a rock.’ You know, you’re redirecting it, and I think we grossly underestimate particularly children in terms of helping them understand the power that they have to help somebody else. And I think it’s just a travesty in our country and our culture and our economy that we don’t expect more from them, because when I challenge them, they respond in spades.

MS. TIPPETT: Children, yeah.

MR. DUNGAN: Oh, they’re just — it’s marvelous to see how they get it quickly. But it’s because no one has really, to any depth or degree, challenged them to make a different choice. So we subject them to this “see money, spend money” mentality and then that becomes a rhythm for the choices that they make. And it’s not out of, you know, not wanting for your child, of course not.

MS. TIPPETT: No, it’s a feeling of not knowing how to do it differently.

MR. DUNGAN: Precisely. And it’s a feeling like I’m going to be going against the grain, and what will I have to do because of that?

MS. TIPPETT: Financial educator Nathan Dungan. This is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media, today exploring the intersection of money, values, and culture.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a word you use — or “share, save, spend” is the slogan or the headline of a lot of the work you do, but you talk about creating a counter-rhythm, a counter-rhythm to this consumer frenzy that is the rhythm that really feels quite natural to many of us and our children.

MR. DUNGAN: The idea of the counter-rhythm and the counter-trend is a bid to sort of raise up this notion that it’s not about throwing necessarily the baby out with the bathwater, but it is about sort of re-looking at the choices we’re making and the things that we’re doing, and perhaps how we’re teaching it or talking about it, and how do we allow that to sort of seep into our being and then respond accordingly.

MS. TIPPETT: And you have this basic idea of, let’s say, giving a child an allowance, yes, and that you kind of make a commitment to share a third of it, save a third of it, and spend a third of it. And is that kind of your basic prescription? It’s a lot more complicated than that, but…

MR. DUNGAN: Well, actually, it’s not much more complicated than that. I mean that’s, I think, kind of the essence of it, is it’s pretty simple. I’m not so prescriptive in terms of that it has to be a third, a third, a third, but, you know. The last time I checked, most 10-year-olds didn’t have a lot of overhead, you know. So part of what I encourage people to do is think about the future and recognizing, you know, the deep trouble that many young adults are in today and our savings rate, which has literally fallen through the floor, and stepping back and saying, ‘OK, what do I need to do as either an individual, a parent, a community, a church? How can we lift up and support people for making different choices?’ And so it’s in that notion of, again, the share and the save and the spend. It’s that we develop a different kind of habit. Because one of the things, Krista, that I found to be so true is that when I interviewed clients who really — that I thought were doing this money thing particularly well, there was evidence in the choices that they were making of share and save and spend. And there was…

MS. TIPPETT: You could see that as a pattern.

MR. DUNGAN: Absolutely. Over and over and over again.

MS. TIPPETT: I had an interesting experience getting ready to interview you this morning. My son, who’s eight, was looking over my shoulder. And I’m aware of a lot of conflicting emotions in him about money. He’s known it to be a stressful part of our family, which I bet most kids have — they’ve seen their parents struggle with money at different times. He likes the idea of making a lot of money and, at the same time, when we pass someone in the car who has a sign that says they’re homeless, he wants me to empty out my wallet for them. So he has all these different impulses. And I told him, because he’s looking over my shoulder, I said I’m interviewing you and I said, ‘Here’s his prescription,’ because we’ve also never really gotten the allowance thing right and I’m aware of that. I said, ‘What do you think about this idea, you know, you share a third of it, you save a third of it, and you spend a third of it?’ And he thought about it for a minute and then he said, ‘Yes,’ just like that. And it was really deep in him, that it made a lot of sense to him.

MR. DUNGAN: Exactly. If we really agree that young people like boundaries, and most…

MS. TIPPETT: And they do, right.

MR. DUNGAN: And they do. And most child psychologists would say — or virtually all of them would say that’s important, but they also — it’s that sense that they’d also like to help other people and they get — they’re enormously gratified when they have saved for a goal. The beautiful thing about the allowance for families, I always say, is you can just eliminate so many of the negative issues because it’s the very simple parent to child, in a store, nag, nag, nag is going on, you know, and it’s not unusual, but for the parent to be able to turn and honor their child and say, ‘You have money, is that what you want to use your money for?’ it just reframes the entire conversation. But that is not what the people in the marketing world want you to believe. They want you to just make it go away and just hand the money over, buy the thing, and then it’s the pattern and the habit, and so welcome to the counter-rhythm or the counter-trend.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. But here is an instinct I have, and I don’t know if this is my generation. For me, the downside or the daunting thing about your formula that’s so simple is that I’m going to have to spend a lot of time talking to my kids about money. We’re going to have to plan this and structure it and maintain it. And there’s something in me that wants to say, ‘Money is not the be-all and end-all, money is not the center of life,’ and therefore — and not spending a lot of time talking and thinking about it is one way I express that. How do you talk me out of that?

MR. DUNGAN: Right. Well, I would say that it’s happening right now, and that by not talking about it, I always say that the culture will fill the void. And the culture of consumption is in your house, in your place, and absent any intentional process or conversation, it’s there. And so I would say we can default to the no-conversation side, but I would think that what you would find is actually the freedom that it would bring and the sense of your son’s reaction about ‘Yes,’ that that sense of kind of calming, it actually is less troublesome and time-consuming than you might think it would be.

When most families — as I described how I grew up, memories of my parents, they would sit down at the beginning of every month and write out the church offering for the entire month, and I remember just, you know, them being in conversations — I’m the youngest of four, asking questions, etc., and they would just say — when I would ask them, ‘Well, why do you do that?’ ‘Well, you know, it’s a priority for us.’ That’s means you’re doing it before we’re buying food, you’re doing it before, you know, these other things. It was just a priority for them. Didn’t hold it over us. It was just a conversation. And what I found in our family, looking back, is that I actually found it to be very normal and natural. There’s a period, when you create a new habit, a new process…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, where it’s hard, where…

MR. DUNGAN: It’s hard.

MS. TIPPETT: …it feels like it takes a lot of time.

MR. DUNGAN: Does. But then once you kind of push through that and get to the other side, a sense of freedom and a sense of peace and space is very liberating.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you think it’s possible to impose a new discipline like this? We’re having this conversation right here as our culture is entering the peak shopping season of the year. I think this might be the hardest time, perhaps also the most important, I mean, where we’re really aware of the turmoil that these demands and these created needs generate in us and in our children.

MR. DUNGAN: I believe that this issue is really center for much of the tension that exists in families around this time of year because the pressure, you know, you don’t want to have to come clean and say, ‘I can’t afford that.’ You can’t believe the number of families I’ve talked to, at particularly the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, who say that the pressure, you know, that they feel that their kids are going to have the day after the holiday to answer the question, ‘So what did you get for’ — fill in the blank, Christmas, Hanukkah, you know, what have you. It’s unconscionable to me that we have let that happen, and so I think that there’s a deep need inside of people to see a different way, but it needs to be supported.

MS. TIPPETT: Have you also worked directly with other religious groups outside Christianity?

MR. DUNGAN: A little bit. I’ve done some work for some people in the Jewish community. We’re in conversations now with some folks who are Unitarian.

MS. TIPPETT: I notice that you worked with some Mennonites, you had presented to Mennonites.

MR. DUNGAN: Oh, and actually I was just recently with a group of Mennonites — and I’ve been doing some things with the Mennonite church for three years. You know, as you know from their Anabaptist…

MS. TIPPETT: Well, they have an incredible tradition of service.

MR. DUNGAN: Exactly. And social awareness.

MS. TIPPETT: Human service, yes.

MR. DUNGAN: And so it doesn’t surprise me at all that there’s this little bitty sort of group, relatively speaking, who is out recognizing that this is a big issue. And I will actually be going back to a very significant conference that they will be convening, because actually…

MS. TIPPETT: This “How we spend our money”?

MR. DUNGAN: Yes. Yeah, they’re going to — in Southern California, a couple of the churches under this Anabaptist umbrella, right, Friends churches, they’re going to be convening conversations about money and the role it plays in our lives, and they’re going to invite every single faith tradition in Orange County to participate in this conversation. I mean, these people are on fire to convene the conversation, and so in the first weekend in May we will be gathering in Orange County to deal with this issue in an interfaith sort of a way.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s great.

MR. DUNGAN: Yeah. And I think, again — I’ll kind of return to what Jacob Needleman talks about, as he says…

MS. TIPPETT: The philosopher, mm-hmm.

MR. DUNGAN: The philosopher, just his, you know, the calling — the question of saying where is sort of the church in that question? But then I think, where is our society as we pursue this sort of thing around money? And I think once people feel that they have a bit of a support network around them, they’re more apt to make the change and to make the turn. I mean, for you, if you had, you know, people — family and other friends — around you to support that turn, I think a couple things: It would be easier and it would also — you would, again, just get, I think, a lot of joy out of it.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, and also if you knew that there were people who would ask your children the day after Christmas, would ask a different question…

MR. DUNGAN: True.

MS. TIPPETT: …not, what did you get for Christmas?

MR. DUNGAN: Well, or teaching them to say, ‘Well, you know, I got — yeah, I got some things for Christmas, but you know one of the really cool things, from my grandparents’ — this is an idea, by the way, from a client that I had in Philadelphia. ‘From my grandparents, I got this thing called a share check and it’s my job to give it away to something that I’m passionate about.’ And when you get kids excited about that, it’s amazing to see what comes out of them. You know, I have a great story of a young gal here locally who for her — was it fifth birthday party, she had the kids bring, as part of their experience, presents for the Jeremiah Project.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is a project for homeless people in…

MR. DUNGAN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …urban Minneapolis, yes.

MR. DUNGAN: And her parents obviously seeded that, you know, so it’s not like this little five-year-old said, ‘Hey, I want you to…’ So before the birthday party they took her to the Jeremiah Project. Birthday party happens, the things come in, and then they take her there afterwards, and that’s all she talked about, was that experience. And then what does the Jeremiah Project do? They did a little article on her because they thought, ‘How cool, here’s this five-year-old…’ And again it comes back to this point, we underestimate the power that that one counter-rhythm event will have on them. It doesn’t need, I don’t think — 3,000 messages a day, that’s what’s coming at kids, you know, encouraging them to spend.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right. Is that statistically proven…

MR. DUNGAN: It is.

MS. TIPPETT: …3,000 messages a day?

MR. DUNGAN: American Demographics magazine, 3,000 times a day. So by the time they’re 21, you know, they’ve experienced some — upwards of 23 million advertising impressions. And you don’t need a one-to-one ratio to counter that. I mean, that’s the incredibly powerful thing. It can be one little conversation, one nurturing thing here, perhaps from an outsider, you know, this event that happens, but it’s seizing the day, finding that teachable moment, and then letting them just express themselves.

MS. TIPPETT: Financial educator Nathan Dungan. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, is it realistic, is it moral, to talk about saving and sharing and spending money wisely, when some people in our culture today go into debt to finance food, education, and even health care?

MR. DUNGAN:You know, the reality is it comes back to, you know, what is your capacity to do that. But being generous doesn’t have to just be money.

Visit us online at speakingoffaith.org. You can watch behind-the-scenes video of my conversation with Nathan Dungan. Our Web site also features listener stories about the successes and struggles of bringing money into balance in their lives. While there, tell us your story. Also, sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter with my journal, and subscribe to our free podcast so you’ll never miss another program. Listen when you want, wherever you want. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Money and Moral Balance.” My guest, Nathan Dungan, has developed a framework and philosophy for financial planning in families which links values with spending, giving equal weight to saving and sharing money as well as spending it. This creates what he calls a counter-rhythm to the consumer mentality that has helped to diminish individual savings and brought credit card debt among college students to a previously unimaginable level. But I’m aware, as I speak with him, that ours is a conversation of privilege. Some of today’s soaring personal debt is also a matter of survival.

MS. TIPPETT: This is preying on my mind as we speak and I think it is connected to what we’re talking about — I’m not quite sure how — which is the fact that we can talk about affluent Americans or middleclass Americans spending too much on things they don’t need and that’s debt that has, you know, moral and spiritual implications, but increasingly, I mean, this is something someone named Jackson Lears wrote in The New York Times, “Less affluent Americans have resorted to borrowing for groceries as well as cars. Public policies have intensified their plight. One of the most consistent statistical findings of recent years is that half of all personal bankruptcies have been caused by medical bills. Whatever else our current indebtedness may signify, it is hardly a riot of hedonism.” So here’s the other side of that picture of spending, which is just debt as survival.

MR. DUNGAN: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, I guess there are two questions that are raised in my mind about that. One, is this kind of talk of intentionality about money, would this make any sense to someone who’s just struggling to survive? And can this reality in our society be part of what we’re helping our children connect into, who are in the middleclass?

MR. DUNGAN: Right. Well, I think the first part of that in terms of those who are just surviving and borrowing to survive, I would say a good bit of that is policy decisions that we have made, you know, in this country. You look at tax cut policy, you know, you look at a myriad of different things that have basically meant less money in the public domain to respond to some of these things. And here’s a quick example: I serve on the board of Lutheran Social Services, and for every 1 percent of cut that they receive from state and federal government, it necessitates a 10 percent increase in their private philanthropy to break even.

So at a time when deep cuts are made — and we’re making choices, right, and I would say that that comes back to those of us who perhaps have the wherewithal — I guess maybe it’s a question: Are those policy choices a result of our hyper focus on me? And I mean, at some point — when do you ask the question, how much is enough? And so when there you are in the voting booth and you’re making a decision, you know, based on, you know, yeah, I’d like a bigger house, I’d like a bigger car — and I’m not saying — none of those are bad things, you know. I don’t — again, I don’t want to demonize the spending, but it just shows you how deep it runs into our sense of being. And when you live perhaps in a place where you are never surrounded by people in need or perhaps there’s…

MS. TIPPETT: In a good affluent neighborhood…

MR. DUNGAN: Good affluent neighborhood.

MS. TIPPETT: …where everybody else has the same size house.

MR. DUNGAN: Exactly. You know, it’s tough to know the plight of the people who are on the other side of that. And so you asked the question also, do people on that lowest end of the spectrum, do they respond, do they have a need for what I do? And it’s curious because I also chair a board called YouthCARE — and the CARE is an acronym for Cultural Appreciation and Racial Equality — and it’s young urban youth, a multicultural organization, and I have delivered, you know, a version of our workshop and they responded in spades because they, too, want boundaries. And they — one of the…

MS. TIPPETT: Are these kids at different ends of the socioeconomic spectrum?

MR. DUNGAN: Well, they’re at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: They are. So they respond well to this idea of sharing and saving and spending.

MR. DUNGAN: Sure. They do.

MS. TIPPETT: Because, I mean, how can we be sitting here, talking about how good it would be for everyone to share and save a portion of their money, when we know that right now there are single mothers who, you know, can’t even pay their mortgage, much less buy new clothes for their children. I know that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be having this conversation, but it’s a troubling reality behind the conversation we’re having.

MR. DUNGAN: Oh, for sure. I mean, I think, you know, the reality is it comes back to, you know, what is your capacity to do that? But being generous doesn’t have to just be money. You know, being generous is about time, being generous is about just how you are to other people, you know, those expressions of gratitude. And quite frankly, you know, I think there again we underestimate the people at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum because, again, all the research has been done and they actually give a larger percentage of their earnings away to causes than those of us who are at the, you know, the middle or the upper end of the socioeconomic spectrum. They show us the way. You know, I think it’s a wonderful, powerful thing to have young people together, from different socioeconomic spectrums talking about this because typically the ones who come away feeling a need to step it up are those at the upper end of the socioeconomic spectrum when they talk to those at the lower end. And it’s just how powerful that sense of, you know, sort of movement and motion and less focus on self is a very significant thing and I just — certainly I can’t talk here…

MS. TIPPETT: You can’t talk to this person that would not be…

MR. DUNGAN: No, that wouldn’t be a good thing.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I’m struck by — listening to you, I was very intrigued by a new study that came out of Harvard just recently, where they had said that the “me” generation had given way to the “we” generation, and that these were kids whose earliest public memories include 9/11, the tsunami in Asia, Hurricane Katrina, and that these kids — who I think are the age you’re talking about, I mean, people who are teenagers now and even younger — are growing up with a sense that the world is very large, that there’s a lot of need out there, and not so self-centered. And perhaps the implication is they won’t be quite so susceptible to these 3,000 consumerist messages they receive every day. I mean, are you picking up a generational shift?

MR. DUNGAN: Oh, I would say most definitely. But, again, it’s got to be nurtured.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. DUNGAN: They may have the — I really believe most young people are generous, you know, quite frankly. I mean, I think — and that’s been — it’s really stood the test of time, but I think absent that sense of intentionality and a process for them to express that.

MS. TIPPETT: So what this generational shift does, it still puts a lot of responsibility, new responsibility, back on those of us who are adults in their lives…

MR. DUNGAN: Squarely.

MS. TIPPETT: …to nurture that and give them, as you say, the boundaries and the structure to live that out.

MR. DUNGAN: Most definitely. And so the challenge becomes, and our choice then is, what do we do with that opportunity? We see this desire, this willingness to change, but what are we going to do to respond and nurture that? I mean, it’s a very wonderful, deep question for us to be pondering, you know, as we race like maniacs, you know, over the next weeks leading up to the holidays. You know, thinking about — there’s this term that I kind of use, and I certainly didn’t create it but it works, and it’s called experiential philanthropy. You know, how do you combine time and money, you know, together intergenerationally, right, as a way to start to nurture that sense of gratitude in place and recognizing the needs of others? Because, I mean, it was really my sense of coming out of 9/11 with this great, you know, opportunity to do some introspection, but I think today, if you asked, you know, the deep thinkers and philosophers, you know, in our world, they would say, ‘We missed an enormous opportunity.’

MS. TIPPETT: To be introspective.

MR. DUNGAN: To be introspective.

MS. TIPPETT: Financial educator Nathan Dungan. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media, today exploring the complex intersection of money and values in U.S. culture and in our families.

In recent years, socially responsible investing has grown as one way to use money to influence the wider world according to personal values. The idea itself has a long history. Quakers and Methodists, for example, withheld investment as early as the 17th century to raise awareness about slavery. Other religious groups have historically boycotted companies that support gambling or alcohol use. Massive Western disinvestment from South Africa put the apartheid regime under significant pressure in its final years. But I asked Nathan Dungan also about the limits of using money to effect social change. Another trend that’s very significant in our time, perhaps that started really gaining traction with the South African…

MR. DUNGAN: Apartheid?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, the divestment campaign, is socially responsible investing. It’s just taken off in these last couple of decades. And what is it, something like now one in 10 dollars under professional management in the U.S. is involved in socially responsible investing. And, of course, that’s good. But a question that’s raised for me, and also about this idea of kids sharing their money, is that money still holds us at an arm’s length from real human need. How do you think about that?

MR. DUNGAN: Sure. Well, and I think that’s why this notion of experiential philanthropy is so critical.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, that you just mentioned.

MR. DUNGAN: I think it’s again about what a wonderful thing of circling back to that very simple little system of having kids and the choices with their money, right, the share-save-spend idea. It gives them some freedom to start to explore: ‘What do I want to do with that?’ You know, it’s that wonderful challenge, and that just opens up this different world. ‘Well, no one’s really ever asked me to think about giving some of my money away.’ And with the e-thing, you know, the wonders of technology and some terrific organizations…

MS. TIPPETT: They can go online and find out what they can do with it.

MR. DUNGAN: Well, I think that’s a beginning, you know, and I think it’s a beginning of an awareness and a sense of — that you’re asking them to be thoughtful about that.

MS. TIPPETT: What about some of just the basic realities of the world we inhabit now and how that’s changing, and how technology, which can become large purchases — and not just games, that’s one thing, but, you know, having the computer, having the cell phone, having the iPod, having the MP3 player, all of which are tools for kids to become more aware of the world and asking more important questions, that these become necessities, and yet they are expensive.

MR. DUNGAN: It will be — 25 percent of our purchases this holiday season will be on electronic gadgetry, so it’s rising exponentially. But I would also issue a bit of a caution because one of the great ways and new ways that marketers and advertisers reach young people, for example, is via cell phone, and it’s the little drips of information delivered in just little two-second increments, right, over the course of a screen on a cell phone that should give us pause.

And the reason I say that is this year Disney introduced a cell phone directed — target age was, I think, six to 11. I always ask people, what do you think the predominant reason is that they market that phone? And mostly it’s on, you know, child protection and safety and, you know, those kinds of things, you know, because, you know, a lot of families are dropping off their five-year-old at the mall, you know, wanting to know where they are. But the real reason is because — there’s another reason, I should say, and it’s because technology already exists in the world where you can have financial information kind of loaded onto a phone and you can just literally wave it like a wand and it does purchasing for you instantaneously. So it’s a little bit of a heads-up to recognize that through the benefits of technology and learning about the world — again, it’s a boundaries issue to say how do I make choices that are responsible for who I am, what I am, in the greater sense of place in space and recognizing that, you know, places like libraries also afford us a wonderful opportunity to access technology. You know, we constantly feel the pressure to have to acquiesce and make sure that we’re of the norm, and I think that’s one of the beauties of coming together as a community to start to talk about that, is it gives you a platform to put that stuff on the table and also really start to get you, you know, the rebalancing back to what is really important to me, what are my values, and then out of that recognizing I’m going to constantly have this pressure coming from the outside.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. And it’s true, actually, just to think about how individualistic this culture — the technology we need is. I mean, I do. I go to libraries all the time. We could think about some of this being more common shared property, but it’s not evolving that way.

MR. DUNGAN: Right. It’s not saying that a cell phone is a bad thing. I mean, of course not. I mean it’s just — but recognizing there might be some ulterior motives about an eight-year-old, for example, having a cell phone, that maybe we haven’t — we don’t necessarily know the advances in technology, but obviously the people putting them forth certainly do that. And so individuals, I mean, and folks collectively can sort of step up, I think, and start to ask questions. And the way that I see this happening is in the whole childhood obesity issue. Earlier this year, the Federal Trade Communication came out and said they believe now that there is a link between the amount of advertising young people get for unhealthy food and their eating habits. Well, you know, isn’t that rocket science? But then I say, well, let’s take that question one step further. If that’s true, wouldn’t it also be true that — and remember, food advertising is only just a part of the, you know, messages to consume that kids get.

MS. TIPPETT: So you’re saying obesity is something that’s visible, that we can see, but there are other kinds of excess and unhealthy excess there inside our kids.

MR. DUNGAN: Well, and there are, and I think they sometimes slide under the radar screen. But I think, out of that, people will say, well, gosh, how do you have hope in this? And I say my great hope is in — when I see young people respond to the message, it’s really powerful. And then subsequently when I see parents and grandparents in a room together with them, having these conversations and just, you know, what that brings forth in them and the possibilities and the power in that is significant, and it’s back to that idea that, you know, step by step, little by little, we make our way in the world. And then how do we help and inspire particularly a young person to make their way in the world? You know, it’s not like we’re looking for the next Gandhi, although that would be fantastic if that was discovered, but I think we’re really looking to pull them into a different kind of a conversation, away from just this hyper focus on self and this just more macro view of the world. And it’s in that rhythm and understanding of what that is that they start to find themselves in a way that allows them to acknowledge what that means.

MS. TIPPETT: What that means, what’s happening in the rest of the world…

MR. DUNGAN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …how they might make a difference in terms of their money and otherwise.

MR. DUNGAN: Well, I mean, think about it. Today, young people 18 and under in America spend and influence the spending of $1 trillion. That’s a phenomenal sum of money. I mean, imagine the good that it would do in the world if we — just a little bit of that were sort of redirected to the Sudan, you know, to places again around the world, I mean, of which there are many, in our own backyards. I mean, what if they just started to — and, again, that’s that sense of there’s that great “we” generation, opportunity, but it’s critical that we nurture that. We’re at this sort of, I think, point that we will either propel them to do remarkable things, or we will perhaps miss the opportunity.

MS. TIPPETT: Nathan Dungan is president and founder of Share-Save-SpendT, and author of Prodigal Sons and Material Girls: How Not to Be Your Child’s ATM.

In his 1994 book, God and Mammon in America, Princeton sociologist Robert Wuthnow described his major national study of the ambiguous relationship between Americans’ professed spiritual commitments and the lives of work and money that we lead. Questions he raised in that study are still before us now, all the more starkly with a backdrop of this season’s shopping chaos. How much longer can we continue at this pace? Can we cut back our material desires and still be happy, especially as economic conditions yield less prosperity in the years ahead? Furthermore, given the pressures most families are now experiencing, can we still pursue the ideals that animated us in the past, ideals of helping the poor and providing social justice for all?

I found the value of this hour’s conversation in part in the simple act of naming such questions out loud and acknowledging the unease they touch in me. And in Nathan Dungan’s insistence that we need to support each other in holding these questions and creating new habits, he echoes Robert Wuthnow’s findings of a decade ago. Neither Dungan nor Wuthnow suggest that people who succeed in reconciling their values and their ideas about themselves with their use of money need a heroic vision. Money is a meaningful reality and a necessity of modern life. But a too-modest vision is equally flawed. It simply can’t withstand the pressure of advertising and consumer culture that, as Dungan points out, will fill any void we leave in reckoning with money intentionally. “We as individuals may not effect sweeping change in our society,” Robert Wuthnow concluded, but he wrote that “we can do more than simply affirm the way things are. We can do this by joining with others — in churches, in synagogues, civic associations, and small groups — to reflect on our priorities, to talk about the difficulties we face in our work and our spending, and to bring spiritual values to bear on these issues.”

We’ve started a version of this conversation on our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. Some listeners have already shared their thoughts and struggles and solutions. We’d like to hear yours as well. We also offer an e-mail newsletter and a weekly podcast. Sign up for free so you’ll never miss another program again. Listen when you want, wherever you want. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and editor Ken Hom. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with assistance from Jennifer Krause. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith, the executive editor is Bill Buzenberg, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.