Nicholas Kristof

Journalism and Compassion

Can journalism be a humanitarian art? New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof has learned that reportage can deaden rather than awaken the consciousness, much less the hearts, of his readers. He shares his wide ethical lens he’s gained on human life in our time — both personal and global.

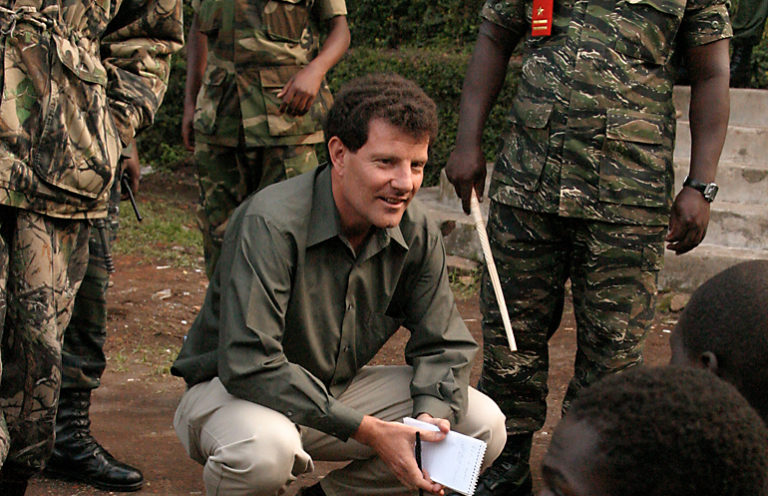

Image by Will Okun, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Nicholas D. Kristof is a columnist for The New York Times and a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner. He is also the co-author of the best-selling book, Half the Sky.

Transcript

February 9, 2012

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett.

Nicholas Kristof has won two Pulitzer Prizes covering some of recent history’s worst atrocities — the Tiananmen Square massacre in China; genocide in Darfur. But he became aware of the reality so many of us know as consumers of news — that reporting from devastating situations can be overwhelming, numbing our sense of whether it matters that we care, what difference we could possibly make. So Nicholas Kristof began to draw on new science that reveals the limits of human empathy — why it shuts down, and how to open it again.

I gained a new appreciation for his journalistic ethos through an HBO documentary, “Reporter,” that followed him to Congo. We’ll listen to some scenes from that film, as we explore what Nicholas Kristof has learned from looking straight on at some of the hardest things in the world.

“Journalism and Compassion.”

I’m Krista Tippett. This is On Being — from APM, American Public Media.

I interviewed Nicholas Kristof in 2010. He’s been an op-ed columnist for The New York Times since 2001. He followed a well-trodden path to the Times — writing for The Harvard Crimson as an undergraduate, freelancing as a journalist while studying law as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. And he had two university professors as parents. But Nicholas Kristof’s father was also an Armenian-Romanian immigrant, who came to the U.S. after surviving his own political traumas. And he raised his son on a farm in Oregon reminiscent of the lost land of his childhood.

MS. TIPPETT: First of all, I just have to say you grew up on a sheep and cherry farm, which sounds so lovely and also a little bit is a funny juxtaposition — sheep and cherries.

NICHOLAS KRISTOF: Well, I mean, I think I’m probably one of the few people in the New York Times newsroom who knows how to weld or give birth to a lamb.

MS. TIPPETT: Although both of your parents were scholars.

MR. KRISTOF: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: And I also just wonder, if you look at your childhood, do you see the roots of what’s really become very defining about your journalism of an interest in compassion and empathy in human life and a kind of longing to spark that in people?

MR. KRISTOF: Well, I think that I always had some interest in individuals, some drive to try to make a difference, and I think that was one of the things that attracted me to journalism. But I also think it, you know, would have been entirely possible that I would have ended up a business reporter writing about corporate earnings. And really what changed me onto the trajectory that I ended up on is that I went out and was assigned abroad, lived a good chunk of my life abroad, and just encountered poverty. And that was just, you know, life-transforming. That once these issues become real and you see these things, you know, you can’t forget the people you meet and you want to try to make a difference in some way.

MS. TIPPETT: Where did you first encounter poverty, really, in that way?

MR. KRISTOF: Maybe when I was a student at Oxford. I used to spend the vacations traveling around, you know, with a backpack. So I remember hopping the ferry from Spain into Morocco and traveling around Morocco and, you know, running into a little girl who was begging and taking around her grandfather who had river blindness and was blind. You know, they were begging and they could communicate a little bit in French. You know, all of a sudden, she was very real, her grandfather was real, and you could imagine them as, you know, people that I’d grown up with or members of my family.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KRISTOF: You know, it just seemed so horrific that this kind of thing should still be happening.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, something that has impressed me over the years in your journalism is that you’ve talked about and kind of revealed moments of learning in public — and then there’s a sense in which you’ve been more — I don’t know if vulnerable is the right word, but open, which journalists aren’t always, you know. Of course, when you’re reporting on things, you’re learning, but then you present it as information. Columnists, I think, you know, wield opinions, let’s say, more than you do. But you often yield moments of discovery and you’re very clear that you discovered something and you didn’t know this before. I’m just also curious about, you know, is that an experience you had of journalism early on, or is that something that has developed for you? Do you know what I’m talking about?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, maybe because I lived for years in China, I’m very suspicious of ideologues …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KRISTOF: … of whatever complexion, and I think it’s really important to learn empirically and to test your ideas and, you know, occasionally be wrong. I also think that it’s more — that you’re more persuasive when you acknowledge that, you know, you have changed your views and you explain how that process happened. You know, you do feel a little bit naked when you confess …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KRISTOF: … in a column that you screwed up.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KRISTOF: But I think that it ultimately gives you a little bit more credibility with readers.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. So I spent part of this morning watching the documentary that’s been made about you, “Reporter.” I’m assuming you’ve seen it.

MR. KRISTOF: I have.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. KRISTOF: It’s a little — it’s a strange experience to watch yourself.

MS. TIPPETT: I bet it is. Well, yeah. That’s also another role a journalist usually isn’t in, of being the focus of the …

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah, and that was strange. I mean, I let this camera crew trail around with me in eastern Congo, you know, because I deeply wanted this issue to get a little bit on television. But there were times out there where, I mean, I would have throttled that cameraman if it wouldn’t have undermined my humanitarian image.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KRISTOF: But, you know, but ultimately, I was so impressed with what he did, and I think it really did help get the word out about what is happening there.

MS. TIPPETT: I think it does and will, and I also was really impressed with it. In as much as Congo is the focus, I think also a big interest for the people making the film and for the people watching it is, again, what motivates you as a journalist. So, you know, there’s a line right at the beginning — I think you’re walking in Rwanda their at that point; I’m not sure. They’re talking about you and they say, “He’s here with a single objective, to make you care about what’s just over the hills.” So this got me thinking, as a lot of your writing has gotten me thinking, about the role of journalism and the changing role of journalism. We talk a lot about the changing role of journalism in terms of different platforms, right?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: But …

MR. KRISTOF: I mean, I guess the way I see it — when I first got the column after 9/11, after 2001, then, you know, I thought, OK, I’ll be this pundit, I’ll fire out these opinions, I’ll change peoples’ minds, you know, over breakfast. It turned out that it really doesn’t work that way that, by and large, if I write about an issue that people have already thought about, then …

MS. TIPPETT: It should be like the political news of the day.

MR. KRISTOF: Oh, the political news of the day. Then people who start out agreeing with me think I’m brilliant, and people who start out disagreeing with me think I’ve utterly missed the point. And so over time, I came to think that, in fact, the power of a column and maybe more broadly the power of journalism isn’t so much to change peoples’ minds on issues that are already on the agenda, but rather it’s the capacity to shine a spotlight on some issue and then thereby project it on the agenda.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. KRISTOF: And on so many of the issues that I care deeply about, the reason that they’re not being addressed is simply because they’re not on the agenda. And shining a spotlight and making people uncomfortable about what they see in that spotlight, I think truly is the first step toward getting more resources and more attention and more energy dedicated to solving them.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today, with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, on “Journalism and Compassion.”

In addition to spotlighting crises like those in Darfur or Congo, he focuses on global issues below the radar. Many of them have women at their center. And this is the subject of a book he’s written together with his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, called Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide.

MS. TIPPETT: Again to this idea of motivation, do you feel that also this kind of journalism that you’re doing — I mean, shining a light on places and problems that people should know about and should mobilize about, that there’s a shift there in a journalistic ethos as well? I mean, how do you think about that?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, I think traditionally both historians and journalists essentially wrote about what — in traditional terms — what the king said yesterday or, in modern terms, what the president announced. And that, over time, you began to see historians over the last few decades increasingly look at what ordinary people were doing. And likewise, I think we in journalism are broadening our sense of what history is and what our first rough draft should be and looking at these broader trends. And, you know, that was really something that my wife, Sheryl WuDunn, who’s also a journalist, and I, you know, over time we began to rethink what kind of things we should be writing on. In particular, in China, for example, one of the milestones of our careers was covering the Tiananmen Square demonstrations and the massacre that resulted, killing hundreds of people. I was there in Tiananmen Square. I was revolted by what I saw. For weeks, every story we wrote was on the front page.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KRISTOF: But then the next year, we came across a study indicating that every year in China 39,000 baby girls were dying because they didn’t get the same food and health care as boys, and we’d never given one column inch to that issue. And there were something like 50 million women who were missing in China, discriminated against to death, in effect, and we’d never covered that at all. It began to make us think that maybe our journalistic priorities were too narrowly on what governments did and that some of the biggest human rights issues actually had to do with society rather than with governments.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve been really intrigued also by how you have then become very interested, even in a scientific level, at how people will respond to these kinds of stories, right? Outrage fatigue, compassion fatigue is a phrase that’s out there. So what have you learned because even just what you’ve just said about the thousands and millions of deaths, I’m very worried that those kinds of statistics are debilitating and paralyzing for people.

MR. KRISTOF: And you’re right. My fascination with the science of this, with the social psychology and the neurology of this, really grew out of my frustration with what I was writing about Darfur. I’d go out to Darfur and I’d see these villages burned down, kids massacred, women raped, and I would write these columns and it just felt like they were just disappearing into the pond without a ripple. In the meantime, at more or less the same time in New York, I don’t know if you remember, there was a red-tailed hawk named Pale Male that got pushed out of his nest.

MS. TIPPETT: I don’t remember that.

MR. KRISTOF: Well, there was a pair of hawks and the male was called Pale Male and he was living in a condo building on Central Park. He was evicted by the building, and New Yorkers were just up in arms about this homeless red-tailed hawk. And I was sort of frustrated I couldn’t get the same reaction for hundreds of thousands of people being driven out of their homes as for one red-tailed hawk. So that led me to look at the work in neurology and social psychology about what makes us care. As you suggest, it’s not about numbers; it’s not about statistics. It’s really about an emotional connection, and it’s the emotional parts of the brain that light up when the brain is being imaged that lead to some kind of a moral decision. It’s not the rational parts, and …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. But there’s some way you put that and somewhere you said that the emotional response becomes a portal and then rational arguments like numbers can play a supporting role.

MR. KRISTOF: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s really interesting.

MR. KRISTOF: That opening, that connection, that empathy, is really an emotional one. It’s done based on individual stories. And we all know that there is this compassion fatigue as the number of victims increases, but what the research has shown that is kind of devastating is that the number at which we begin to show fatigue is when the number of victims reaches two.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Would you tell the story about Rokia and Moussa, the photograph that they used to illustrate this?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. This is from the work of a psychologist called Paul Slovic. There were experiments where people were shown a photo of a starving girl from Mali called Rokia, a seven-year-old girl, and asked to contribute in various different scenarios. And then also a boy named Moussa. And essentially people would donate a lot of money. If they saw that Rokia was hungry, they wanted to help her. Likewise, when they saw a picture of Moussa, they wanted to help him. But the moment you put the two of them together and asked people to help both Rokia and Moussa, then at that point donations dropped. And by the time you ask them to donate to 21 million hungry people in West Africa, you know, nobody wanted to contribute at all.

MS. TIPPETT: Because they’re overwhelmed by that, or it doesn’t spark the same reaction that actually enables people to act. Is that …

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I think it’s not real. I mean, I think that my job as a journalist is to find these larger issues that I want to address, but then find some microcosm of it, some Rokia who can open those portals and hopefully get people to care. And once that portal is open, then you can indeed begin to put in some of the background, some of the context, some of the larger issues, and hopefully get people to engage with that issue.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, again in this documentary film, “Reporter,” the narrator is young from my imagining …

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah, that’s reasonably true, which means younger than me.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, or me. You know, I wonder, in the Congo, he’s saying, you know, that what you’re looking for — you talk to a lot of people who have been suffering in a lot of ways. You see some terrible things, but he says you’re looking for your Rokia, for this story.

[Sound bite of “Reporter”]

NARRATOR: The next morning, we were out again. By this point, I had grown deeply suspicious of Nick’s method of seeking out the worst suffering in order to tell a story. But my misgivings kept crashing into the same hard logic — that the saddest stories exist whether or not Nick finds them. And if those stories have the greatest capacity to inspire action, then Nick’s strategy makes sense functionally. Regardless, this kind of dismal illumination doesn’t feel very good.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you have misgivings about that too, even as you’re talking about the scientific basis for it.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, I periodically do. It does feel sometimes a little bit manipulative. The other aspect of it is that people connect with stories that are kind of ultimately positive or triumphant. They want to be a part of something successful. And so when Sheryl and I were writing our book about women around the world, Half the Sky, we were very much looking for stories of individuals that would plumb the depths of terrible things that happen, but ultimately end on this kind of inspiring, happy note.

And that in particular I — you know, I worried a little bit about. If we’re selecting stories of women who, whatever, have been trafficked or gone through a fistula or whatever it may be, through some kind of deplorable sexual violence, but ultimately have triumphed in some unbelievably wonderful, inspiring way, then, you know, is that a little bit too manipulative? Is that going over a line? Is that unrepresentative? I mean, ultimately that’s what we did because we were afraid that, you know, people are turned off by unremitting despair, and you need to show that one can make a difference. But I do worry about that, absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Another thing that it made me wonder — not just that, but the science of this and what you’ve learned, that you could go and you could tell the whole horrific story with all the numbers and that, in fact, would not mobilize newspaper readers across the world the way one thinks it should. You know, when you use word genocide now, ever after, after the Holocaust, as people do with Darfur, they use the word genocide; you use the word genocide, I think.

MR. KRISTOF: I do.

MS. TIPPETT: We think back to an idea we have, I believe, in the West that, if we’d only known, right? If it had only been covered, that holocaust, that surely it wouldn’t have unfolded as it did. I don’t know. I think that what some of this stuff you’re learning suggests that that might not be true.

MR. KRISTOF: Darfur is, I think, a window into that issue because, in past genocides, one could make the argument, not always terribly effectively, but one could at least try to make the argument that, at the time the killing was going on, we didn’t really fully know. We didn’t have a complete appreciation of just how awful it is and if only we had known. And in fact, in the case of Darfur, we knew exactly what was going on. And it was on television; it was in the news and, you know, it has now gone on in one degree or another longer than World War II did.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Something else I wonder about is, you know, many of the kinds of things you talk about, for example, your work with your wife, Sheryl WuDunn, on women. There are kind of words and phrases that people go around thinking themselves should be galvanizing, mobilizing, like human rights or injustice, are in fact very controversial, very politically laden. They’ve got ideological connotations for some people. I wonder if you think about that, about vocabulary and about having to shake up, I mean, even not rely on phrases that one thinks should be effective.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, I’m very engaged in what I’m writing about — Congo or Darfur or any of these issues, and really trying to grab the reader. You know, I know that your average reader, if they come across my column on the subway to work and they see that it’s about Darfur, for example, you know, OK, they’ve got to be at work in 30 minutes, they know terrible things are happening in Darfur, but it’s not really going to be relevant to them that day and they’re likely to turn the page. So I try to use whatever mix of headline, engaging first sentence, occasionally in the case of a headline, maybe a little bit of bait and switch, to try to, you know, to suck people in.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm, and not assume that there’s any code or shorthand that’s going to be universally interesting or appealing.

MR. KRISTOF: No, and I think that, in fact, we tend to, in journalism especially and probably especially in opinions, we tend to speak to our own communities and we tend to recite the arguments that are most persuasive to those who already want to do whatever you do, but are often least persuasive to those who come at this — you know, who are skeptical.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: At onbeing.org, watch extended scenes from the HBO documentary about Nicholas Kristof in Congo. Also, learn more about the children — Rokia and Moussa — at the center of Paul Slovic’s unexpected findings on compassion fatigue.

When I interviewed Nicholas Kristof in 2010, his energies were very much focused on Congo and Darfur. Since then, he’s spent a great deal of time in the Middle East, where he’s telling the still-unfolding story of the Arab Spring. And as technology evolves, he’s making active use of social platforms like Facebook and Twitter to expand conversation about the complexity of all that he’s witnessing.

Coming up, Nicholas Kristof on why victims can’t always be believed, and why he’s stepped up — controversially for some of his readers — to praise conservative Christian activists he once dismissed.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: “Journalism and Compassion,” with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. He’s won his two Pulitzers covering a massacre and a genocide. But he learned that such reporting can deaden rather than awaken the conscience, much less the hearts, of his readers.

The journalistic approach he’s developed in response is the subject of a documentary film, “Reporter,” that followed him to Rwanda and Congo. He’s been describing how he uses his column to bring faraway cultures and conflicts alive by way of individual human stories. Nicholas Kristof has reported in over 140 countries.

MS. TIPPETT: I’d like to talk about some of the things that you’ve written about that you’ve learned in all your travels and all the stories you’ve covered that I think are counterintuitive …

MR. KRISTOF: OK.

MS. TIPPETT: … or that might sound counterintuitive. So for example, I started thinking — I wrote down this realpolitik of compassion because you are out there representing, embodying, compassion for many people, trying to spark it with your work, but you’re very pragmatic and you’ve learned a lot. For example, you said there’s a tendency to believe victims and that’s not necessary right.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I’ve learned this the hard way.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. KRISTOF: When you go out and you come across some brutal injustice, soldiers who’ve massacred people, then the immediate tendency is not only to feel sympathy for those who’ve been butchered, but also to believe their stories. And, you know, in fact, it turns out that victims lie just as perpetrators lie. And they are so outraged by what has been done to them that they often exaggerate, and you have to be just as meticulous and insistent upon verification when you’re talking to those victims as you would be skeptical when talking to the perpetrators.

MS. TIPPETT: Something that really struck me in the documentary and this is also things you wrote about. You met a warlord, a Congolese warlord. There is so much paradox there. I mean, for starters, right, this line between who’s the victim and who’s the perpetrator is thin, right? Because, I mean, he started out as a victim.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah, and perpetrators usually claim that they are victims and that is why they have to massacre the other side.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Then there was the religious fervor, that Christian fervor, which seemed — I mean, in this case because it was filmed, I got to watch it too.

MR. KRISTOF: Well, you know, I couldn’t believe it when this warlord who, you know, was well-known for being involved in mass killings and mass rapes and just brutal predations of people there, he came out with a button on his chest that said, “Rebels for Christ.” You know, where did that come from?

MS. TIPPETT: In fact, the warlord’s officers and soldiers prayed over refreshments they offered Nicholas Kristof and two student journalists he brought along on that trip to Congo.

[Sound bite of “Reporter”]

MS. TIPPETT: I have to tell you that I was watching this and my 12-year-old son walked in and he hadn’t seen anything else. He said, “You know, those guys don’t seem so bad.” And you know what he was seeing too. I mean, there was a real charisma about the warlord maybe not so much, but the people around him.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, frankly, that is often true. You know, if you go and — I often do try to go out and sort of seek out the perpetrators partly because, frankly, I want to understand what it is that drives some people to go and butcher children. You know, what makes those people tick?

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, what have you learned about that?

MR. KRISTOF: I’ve learned that people have an amazing capacity for self-delusion, to feel themselves threatened and then this is the only way to address the risks to those they care about, and that, in general, even the most savage butchers will treat their own little community, their own clan, their own friends and, fortunately for me, their invited guests, with, you know, considerable courtesy and warmth and friendship.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, how does that — this idea of what it means to be human. I mean, how does that change your thinking about humanity and the world your children are growing up in?

MR. KRISTOF: I think that, when Sheryl and I lived in Japan, I was fascinated with the older generation of Japanese who had committed unbelievable atrocities in China, the Philippines, and so many places, and yet were the most courteous, civil people who I could have imagined. And I interviewed an awful lot of them. And I think that one of the things that struck me was just how fine a line it is and that, when you feel threatened and when there are especially a kind of a group of you, this mob instinct can take over and you — we — are capable of doing things that, you know, ultimately later we can’t believe we did, that we’re ashamed about. And I think this is something that, you know, it’s a human tendency that we really need to push back against very deeply when we do feel these kinds of fears.

MS. TIPPETT: I think something that’s related to that that you also have emphasized is the importance of security and maybe even taking precedence over, whether we’re talking about democracy, that it is a prerequisite for helping alleviate poverty. I’m not sure that’s a message people want to hear. It’s something that’s come through so much in my conversations about a lot of subjects over the years also that one of the things in this culture, in the U.S., that we take for granted and don’t realize we take for granted, don’t realize how much it makes possible, is the rule of law — this seemingly simple fact of life.

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I mean, there is always the tendency to think that the most humanitarian thing you can do is to go build a school, build a hospital. And I remember in Central African Republic coming across a clinic — well, the only thing left of it was a little sign out front saying, “Built by the German Aid Agency.” You know, because people were willing to build clinics, but they weren’t willing to help provide security, so some warlord had come through and burned it and who knows what had happened to the doctors and the nurses and the patients. I saw the same thing in Chad, for example, that once you lose security, then farmers can’t go into their fields, so they starve. You know, people sometimes sell their daughters. You can’t begin to address other humanitarian needs until you begin to address security. And I think that that — especially in the aftermath of Iraq and the mess in Afghanistan — it is something that is, you know, really hard for us to figure out how to do and even hard for us to talk about as a humanitarian issue.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, you also write about how some of the things that we look at as problems, like a sweatshop — I mean, you’ve written a lot about this. It’s not necessarily the problem that we imagined.

MR. KRISTOF: That’s true. I’m one of the few Americans who is truly sympathetic to sweatshops really because of the time I spent in Asia and seeing the way they became an avenue for people to ride the escalator up and that they provided a lot of employment for people, which tended to be wretched jobs, but usually not as wretched as working in a rice paddy or in construction jobs or selling cigarettes in the street or, you know, a million other jobs that tend to be available. My fear has been that the hostility to sweatshops has meant that manufacturers don’t go to Africa. I mean, Africa’s problem isn’t that it has sweatshops; it’s that it doesn’t have any sweatshops. And typically, the only thing worse than a sweatshop is indeed no sweatshop at all, no employment whatsoever. I mean, I guess the other thing that I really do worry about — I mean, if I were critiquing my own kind of approach, just between you and me …

MS. TIPPETT: I won’t tell anyone.

MR. KRISTOF: It would be often I focus on things that go wrong, that when I write about Africa, for example, so much of it is about the Congo or Sudan or about AIDS in southern Africa or about malaria or pneumonia, whatever it may be. That conjures an image in the reader of a continent that is completely screwed up, that doesn’t have anything working out for it. And the upshot of that is to dampen tourism, dampen business investment, and just leave people discouraged about the possibilities of the continent in a way that is really misleading. I mean, there are a lot of parts of Africa that have been incredibly successful. So that is something that troubles me and that I try to adjust my coverage to convey that more complicated reality. But that is something that I worry about in my kind of reporting.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you think that your early experiences in Asia and your enduring interest in Asia gives you a certain kind of perspective on the possibilities in Africa’s future?

MR. KRISTOF: Yes. I’m always struck that development experts who’ve spent their careers in Africa tend to be pretty pessimistic. You know, development is just difficult and tough and you strive and maybe you’ll make a little bit of difference somewhere. Meanwhile, development experts who’ve spent their time in Asia, they sort of assume, ah, you toss out a few seeds and next day you’ll have a big field. So in my time abroad, I saw the sprouting of China, I mean, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, all these countries. And they had different economic models. It wasn’t, you know, one precise model, but it led you to believe that places are not hopeless and that we really can see just complete transformations that end up more or less eliminating the worst kinds of poverty.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett with On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today: “Journalism and Compassion.” I’m speaking with op-ed columnist and author Nicholas Kristof. Some of his controversial writing has been about gaining a complex, contradictory view of religion as a force in the world. He’s written critically as well as appreciatively, over time, about the Catholic Church, Islam, and Pentecostal and Evangelical Christianity.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote, I think this was in 2008, you wrote about Evangelicals as the new internationalists. You wrote this: “Liberals believe deeply in tolerance and over the last century have led the battles against prejudices of all kinds, but we have a blind spot about Christian Evangelicals. They constitute one of the few minorities that, on the American coasts or university campuses, it remains fashionable to mock.” What was the response you got to that column?

MR. KRISTOF: It was absolute outrage from the coasts.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, and the university campuses?

MR. KRISTOF: And the university campuses. And people who were, you know, incredibly indignant and saying that, you know, these are people who are spreading bigotry and hatred, and the proper thing to do is precisely to stand up to that kind of hatred and bigotry. I’d say, from the Evangelical community, there was sort of a stunned, but somewhat welcome — you know, people were pleased, but sort of surprised. I’m not sure if it’s that column or a different column, but writing about Evangelicals’ work in Africa, the headline was “Hug an Evangelical.” And a little bit later, one of the Evangelical organizations that I never agree — maybe it was Focus on the Family, of course, which I disagree with 100 percent. They had a headline saying “Hug a Liberal.”

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, that’s good.

MR. KRISTOF: Yes. It was the beginning of our …

MS. TIPPETT: You created empathy.

MR. KRISTOF: Yes, exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, in some place, you suggest that bleeding-heart liberals need to reach out to bleeding-heart conservatives. I was going to ask you if bleeding-heart conservatives reach out to you. That sounds like maybe an example of that.

MR. KRISTOF: No, they actually have. That really is something I believe in deeply, that, you know, if you look at sex trafficking, for example. This is one of the true outrages on the scene today, that there are probably more girls who are trafficked against their will today than people who were enslaved at the height of the slave trade. And they are more disposable because they’re worth less money; their sales price is lower today than it was in 1860, after adjusting for inflation. So there’s this huge issue here, and liberal feminists, secular feminists, are doing great work on it. Right-wing Christian Evangelicals are doing great work on it, but because there is this incredible gulf of mistrust between them, they tend not to cooperate. You don’t even tend to have a similar vocabulary with which to address the issue. The right tends to talk about prostitutes; the left tends to talk about sex workers.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, that’s interesting.

MR. KRISTOF: And each side is just very suspicious of the other. But we’re not going to make progress on this and, you know, we’re not going to get those pimps in jail where they belong unless left and right and secular and religious are more willing to hold their nose and work together.

MS. TIPPETT: Someplace someone asked you who your favorite philosopher was and you said it was Isaiah Berlin. Do you remember that?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah. I was studying law at Oxford and, of course, law is one of the more boring things you can possibly study, which is why I ended up as a journalist, or I’d been a lawyer. But it’s also why I began sort of reading more philosophy on the side, and I encountered Berlin’s work and met him. I think what appeals to me most about Isaiah Berlin’s writings is that so much of philosophy and so much of the Western world has been to search for the one true answer and whether it’s utilitarianism, whether it’s some kind of a Kantian categorical imperative, or whatever it is that we try to maximize and search for …

MS. TIPPETT: Whether it’s the ideology of left-wing feminism or right-wing Christianity.

MR. KRISTOF: That’s right, that’s right. But there is this search for, you know, the one true answer. And Isaiah Berlin emphasized that it’s more complicated than that and that there is maybe this deeply imbedded belief, you know, yearning for one answer, but that in fact there are many different things that we value. And they are incommensurate — that you want to maximize happiness, but the happiness yardstick, you can’t make it link up with the dignity yardstick or the human rights yardstick or whatever it may be. And that these trade-offs are just a part of the human condition and that we have to struggle and search for answers and, at times, acknowledge that this is a tentative answer. We’re not sure that we are right. And yet even acknowledging that, still act on that. You know, one of the problems, I think, for liberals is that they become paralyzed by complexity and paralyzed by the possibility that they’re wrong. So Berlin, you know, in this very messy 21st-century world, Berlin kind of conveys a reality that speaks to me, and that helps me resolve my own challenges in life.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I’ve noticed that a lot of times when people interview you, they remark that you’re less depressed and depressing than they expected you to be. Have you noticed that?

MR. KRISTOF: You know, people must think that I just sort of sit around, that I’m like Eeyore. But, in fact, you go out and, you know, you write about these terrible things happening around the world, but I come back not fundamentally depressed by them as just inspired by our capacity to make a difference, to respond, to do the right thing.

Now on that same trip to the Congo that was in the movie, we saw the warlord and, you know, I was infuriated by him. But the person who I think spoke to me the most on that trip was a Polish nun in the town of Rutshuru who I met who was there in this little town that had been pretty much abandoned by aid groups. It was surrounded by warlords where there were killings every day, and she was singlehandedly feeding orphans, educating kids, staving off the warlords. And I was just so inspired by that kind of commitment to humanity, to trying to make a difference that it ultimately fundamentally left me reassured rather than depressed about humanity.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: So just going back to an early story you told about covering Tiananmen Square, which was a huge world event, which was on the front page of the papers for days. And then, as you said, in the year that followed, you and your wife, Sheryl WuDunn, who’s also a journalist, became aware of this, in fact, much larger tragedy that was unfolding all the time of violence to girls. Right now, we could all easily draw a list of what’s going to be on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow. You know, Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, some kind of seeming clash between Islam and the West, climate change. But I wonder, as you look around right now, you know, what are things you know about that are under the radar, that are just as important, that you’re watching?

MR. KRISTOF: Well, we wrote — I mean, the evolution of finding out what was happening in rural China towards women was eventually writing this book in which we do argue that just as the central moral challenge in the 19th century was slavery, and in the 20th was totalitarianism, in this century the paramount moral challenge for the world will be the abuse that is directed toward so many women and girls around the world. I truly think that that is going to be one of the great subtexts of this century. You know, to get girls into school, to offer them opportunities, to stop bride burnings, sex trafficking, genital cutting — you know, this whole panoply of practices.

So I think that that is one of the great undercurrents and the question of whether countries can make better use of the female half of their population. I mean, one of the things is to determine how successful they are and how stable and peaceful they can be. I think that would be one that I would emphasize. Another would be the question that, for all of human history and indeed for all of humanity, people have, by and large, many of them have lived in poverty. And in this century, we have the capacity to really end that extreme poverty and the question is whether we can really muster the political will and capacity to take those steps so that it will indeed be eradicated.

MS. TIPPETT: And I think the analogy you draw is very interesting because there was political will and political movement eventually around slavery, for example. I mean, from where you sit, can you imagine that kind of energy, that kind of action, around these issues of women and — and of poverty?

MR. KRISTOF: Yeah, I really can. I think it’s very hard to predict what issues will engage people, but I think that, just as in the 1780s, once people became aware of what life was like on a slave ship, then they were revolted by it and couldn’t stand it. I think in the same way that, you know, once people realize what goes on in forced prostitution, that they, you know, will react to it and will want to have those brothels closed down. And once they also see the opportunity that is created by educating girls and just how cheap it is and how much that can bolster an economy, that that will be an opportunity they will not want to pass up. So I think that things are coming together and that this kind of change is taking place already. You know, the question is just whether we’re going to end up watching it or being a part of it.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Nicholas Kristof is an op-ed columnist for The New York Times. He’s co-author, with his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, of Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide.

At onbeing.org, read all of the Kristof op-ed pieces we discussed in this hour and watch that documentary scene of him meeting a Congolese warlord. You can download a free copy of this show or listen to my unedited interview with Nicholas Kristof. Again, that’s onbeing.org. And “like” us on our Facebook page at facebook.com/onbeing.

And follow us on Twitter; our handle: @Beingtweets.

This program is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Susan Leem. Anne Breckbill is our Web developer. Special thanks this week to Stick Figure Productions

that created the “Reporter” documentary and to Will Okun for the photos of his time in Congo with Nicholas Kristof. Special thanks as well to Dave McGuire.

Kate Moos is a consulting editor. Trent Gilliss is our senior editor. And I’m Krista Tippett.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Next time, vocalist, composer, and choreographer Meredith Monk. She’s an archeologist of the human voice. And with a longtime Buddhist practice, she’s become an archeologist of the human mind and spirit too. Please join us.

This is APM, American Public Media.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.