Steve Almond

Ordinary People

Dear Sugars’ Steve Almond talks about the liberating vulnerability of this Robert Redford classic. It taught him to embrace the complexity and pain in his own family, and in the process, move towards a more meaningful life.

Guest

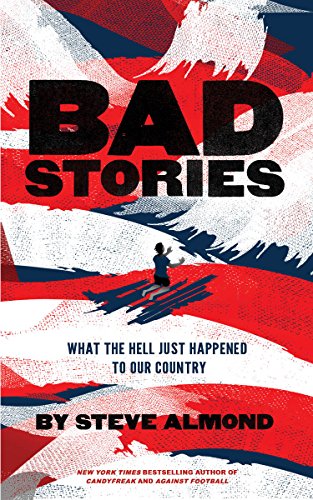

Steve Almond is the co-host of the incredible podcast Dear Sugars. He’s also one of the most prolific and beautiful writers around. His latest book is Bad Stories: What the Hell Just Happened to Our Country. You can find more of his work at stevealmondjoy.org.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Dear Sugars’ Steve Almond about the groundbreaking ’80s movie that changed his life, Ordinary People. If you’ve seen the movie, you’ll soon understand why Steve connected so deeply with it. But if you haven’t, don’t worry. We’re gonna provide all the details you need to understand and feel all the feelings.

[music: “Canon in D” by Johann Pachelbel, arranged and words added by Noel Goemmanne, from Ordinary People: Original Soundtrack]

Ms. Percy: One of the gifts that movies give us is the ability to see ourselves onscreen — to maybe see characters or even emotions represented that we haven’t ever seen anywhere else, that we can’t even talk about or give voice to. And that’s something that Ordinary People does beautifully. It’s really hard to talk about male vulnerability, to talk about depression, to talk about sadness, to talk about not being OK when you’re a teenager. And yet the character of Conrad does that in every line that he speaks and in every facial expression and moment of silence that he represents in the film.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: Ordinary People is about a family who is grieving. They’re trying to move forward and overcome the loss of their son who died in a tragic sailboat accident, but they’re stuck; they can’t communicate with each other about the grief. And that makes them unable to connect with each other.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: Ordinary People is important for many reasons, one of them being that it was Robert Redford’s directorial debut. Another one is that we see Mary Tyler Moore in a way that we’d never seen her before — for the first time, not warm and friendly and inviting and, instead, a more complicated representation of a mother.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: Writer Steve Almond grew up in a family that didn’t talk about emotions. So when he saw Ordinary People, it changed his life, because he had never seen a family talking to each other in such a vulnerable way. And it made him realize the importance of always vocalizing his own emotions.

Ms. Percy: I’d like to take you back in time for a minute by asking you to close your eyes and, for ten seconds, think about the first time that you saw Ordinary People, and think about how old you were, where you were, and how it made you feel. And I’ll chime in when the ten seconds are up.

So what memories came up for you?

Steve Almond: Well, I was probably a freshman in high school.

Ms. Percy: Oh, my god — so close to Conrad’s age.

Mr. Almond: Exactly. And I don’t know what my reaction was, the first time out. It’s become a film that I’ve absorbed so deeply, and it’s been so deeply absorbed into my family culture, especially my brothers and myself, that it’s almost impossible for me to figure out what my initial feelings were, because I have so many [laughs] complicated and intense feelings about it that have really pervaded.

I guess this is now, what, 37 years later — something like that? And I don’t think there’s been a year that’s gone by, maybe not even a month that’s gone by that I haven’t thought about that film, that I haven’t felt something very intense that came out of that film. And I think it’s one of the few films that, when I return to it at every point in my life, I actually appreciate it more.

Ms. Percy: When I first learned that you had chosen Ordinary People to talk about, it made complete sense to me, considering what I know about your work and as a devoted fan of Dear Sugars, because you’ve talked a lot about male vulnerability in your work. And I immediately thought of the struggle that Calvin and Conrad — Conrad, who is the son, played by Timothy Hutton, and Calvin, the father, played by Donald Sutherland — the struggle that they both face in being vulnerable. And I noticed, watching the movie again last night — this was so interesting to me, because I’d never noticed it before — how groundbreaking it was for 1980 that the men are the only ones that we see vocalize and acknowledge their pain.

Mr. Almond: Yes.

Ms. Percy: The father is the one who suggests that his son goes to therapy. He’s the one who worries about him, not the mother. And I’m just so curious as to how that changed the way you viewed yourself, as a man, and the men in your family.

Mr. Almond: So, a little deep background here, because I think, in a certain way, this film represents the two halves of my personality — my parents were both psychiatrists who later became psychoanalysts. And, in a sense, they were very attuned to the inner life, and I was, clearly — as a kid I went to therapy. I was anxious; I was really struggling to feel and make sense of my feelings, so I understood that part of the film.

But the other part of my family history that I think is less obvious to people is that my family was male-dominated — I had a twin brother and an older brother, two years older. And there was — in my family, as there is in every family, Lily — a kind of omerta — a code of silence around deep emotion because it’s just so painful.

So that is really the struggle that plays out in the film. Literally, from the first moment of the film, you see this kid — the first shot is him, singing in a chorus, and he’s actually singing. You can hear his voice. He’s rising — his voice is rising in song. And we move from that, a quick jump cut, to him sitting up…

Ms. Percy: Waking up from a nightmare.

Mr. Almond: …in bed — that’s right, from a nightmare, and he’s haunted. That voice of absolute anguish and guilt and rage and confusion is completely muzzled within him. And what the film captures, in a way that is an exaggerated version of what every family struggles with and, certainly, what my family was struggling with and what I was struggling with, is the desire to have the truth come out and a countervening desire to keep it inside and keep it locked in and not let those dangerous, volatile feelings out of the tightly guarded world inside of us. And you see it in every moment.

And what’s so striking and unusual is that it is a film in which it is the dad who is the compassionate figure, who is trying— even though he’s been acculturated to stiff upper lip and try to keep it all inside — he recognizes that his kid’s in trouble, and it’s really the mom who cannot really forgive him for being the child who survived. She cannot reach across this chasm. She’s just in so much pain that she can’t even begin to let it out. And it sinks her.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: And also, you really get a sense in the movie, with her character in particular, the dual roles she has to play, as mother but then, also, the public persona she has to keep up. And it made me think about your own relationship with your mother, Barbara, because you’ve talked a lot about that, and you even did an interview with her when her book came out, The Monster Within: The Hidden Side of Motherhood, that I thought was so brave of you to do that, publicly — do an interview with your mother. And it showed how honest and direct your relationship was with your own mother, which is very different from what we see Conrad and Beth exhibit in the movie. And it just made me curious as to what the journey was like with your own mother, to get to where you ended up.

Mr. Almond: Yeah, well, I have to be honest in saying that the work of my mother’s life, in some sense, was understanding maternal ambivalence; that mothers are expected, by the entire culture, to be warm and loving. And I think this is a common experience, that women, the moment they become mothers, are expected to have a certain set of feelings — the unconditional love, the emotion that’s always ready to flow and nurture and protect and lift up their kids. But I think my mom — I could tell that she was having two experiences. She was a loving mother. She was attendant to us; she was very warm. Everybody, from my wife, all my girlfriends, all my friends — they adored Barbara Almond. And she was an incredibly warm, welcoming person.

But there was somebody inside of my mom who felt very stifled, very anxious, very marginalized. I could see that she was — she would sometimes — we’d be in the car, and she would be whispering to herself. And I knew that it was a kind of anxious whispering that was almost like trying to self-soothe. But it was obvious that there was some deeper set of really complicated and painful feelings that she was having to manage every moment of the day, in addition to managing her three angry, volatile sons, her very sweet but nonetheless self-involved husband. And she really took it on the chin. So I think I recognize, in Mary Tyler Moore’s character, a sort of exaggerated version of, I think, what every mother struggles with, which is this onerous, completely crushing expectation that mothers perform a certain emotional role; that they do all the emotional labor of managing other people’s feelings, even if, inside, they feel real ambivalence about all of that expectation.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: A scene that I never noticed before that really struck me last night, when I was watching it again, is early on in the film, when Conrad comes downstairs, and he says he’s not hungry. He doesn’t want to eat breakfast. Beth immediately takes the plate away, dumps the French toast…

Mr. Almond: “Can’t save French toast.”

Ms. Percy: …and puts it straight in the garbage disposal.

Mr. Almond: And let me tell you a little micro-moment in that scene. It may not come across in radio, but what’s interesting is that — because I know that scene exactly. I can see it in my head. I can see every scene from this film. He actually might have a bite or two of the French toast, simply to please his mother, to please his father. And she takes it away, and you can see him have this — and this is the amazing thing about these performances. They’re so nuanced. There’s so much in there. And he looks up, and you can tell that he’s kind of startled. It’s as if she’s called his bluff and said, “OK, you don’t want to eat? You’re not gonna eat. I made your favorite. It’s French toast. I’m gonna make one offer, and if you can’t bring yourself to try it or eat it, it’s gone.” And it’s really brutal, because you can see, he’s shocked by — it’s really a moment of anger, it’s a rage — because what he’s saying is, “I’m not better yet. I’m still in danger.” And what she knows inside of herself is, “So am I. And seeing it makes me have to just put a muzzle on it.”

Ms. Percy: It’s such a powerful scene.

Mr. Almond: You can see how desperately they need to reach across and try to connect with one another. But they just can’t do it. And it’s staggering and heartbreaking when I see it, because I think, within my family, even my mother, who I love very deeply, I felt in many moments of my life that I did not have access to the most wounded and pained part of her. I could see it in flashes, but essentially, it was hidden from view because she was hiding it away, even from herself.

Ms. Percy: I love that you’re talking about that neediness, because I think that’s something else that really is brave about the movie that it brings up. And it’s often uncomfortable to watch, as the viewer — to see the need that these both people have to connect with each other. And it reminded me, actually, of something you wrote, which — I believe it was for The Rumpus. You said: “Though I love my family, neediness was totally shameful in the house I grew up in. It’s the reason I’m such a militant emotionalist.” [laughs] “The fact that I’m that way doesn’t mean I’m over it; it’s actually evidence that I’m totally hung up on it.”

Mr. Almond: Yeah, of course, and this is why the work I do on Dear Sugars, the work I try to do in my teaching and in my writing, especially, is to get to unbearable feeling. The path to the truth always runs through shame, and there’s a certain amount of — there’s a lot of anxiety along the way too. And I feel like people say, “Oh, wow, you’re so vulnerable.” Not really. I’m trying very hard to reach people, because I know people are in so much pain, and I’m in so much pain. And we’ve got so much that we could comfort one another around if we just weren’t so frightened of how much that can hurt and how vulnerable it makes us.

But that’s because I grew up in a family that very much frowned on deep emotion, and it was really a sign of weakness. And there was, within the sub-family of me and my brothers, this kind of intense macho culture. But interestingly, Lily, my older brother and I — my older brother is a couple years older than me, and he was kind of like Buck in the film. He was a golden child. He was brilliant. He got into every college he applied to. Everybody saw him as bulletproof. But inside, he was tremendously anxious and struggling, really, with his own mental health. And he and I have always — like you do with your favorite films, he and I can quote one another lines all the time. Sometimes, he’ll call me up on the phone, and he’ll just say, “Did I ask you if they gave you shock out there?”

Ms. Percy: [laughs] God, which the swim coach says to him. Oh, God.

Mr. Almond: That’s the swim coach, right? And again, the coach is being insensitive, but the coach is also just being the coach. This is the way we treat mental illness in our culture. It’s something that is frightening, something that we try to see as a defect that can somehow be corrected if we just toughen up. That’s the coach’s line. That’s why he has to quit the swimming team.

And another line that my brother will quote to me all the time — both my brothers: “Give her the goddamn camera!” — this moment where…

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Of family dysfunction — it comes out.

Mr. Almond: Well, it’s not just that. It’s that Conrad has just been really allowed, by the therapist — “You’ve got to feel, and express what you’re feeling, or it’s gonna explode again, and it’s gonna explode in an act of self-destruction. You have to do this.” And he really internalizes that lesson. And then there’s this — Cal, the father, is trying to take the perfect photo of Conrad and his mother and get them both smiling, and he wants the perfect portrait. And Conrad can tell, this is nonsense. This is bull. This is not real. This is fake. And he’s so tired of the fakery; he’s so tired of everybody faking it in his family. And it’s just this moment where everybody is stunned and troubled, but the kid has done exactly what he needs, to save himself.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: He’s really modeling, for us, the way to be vulnerable. I think about him in the scenes with his friend from the hospital, Karen.

Mr. Almond: Devastating.

Ms. Percy: And he is reaching out to her; he’s trying to tell her, “Look, I’m not OK. Are you also feeling this?” He’s doing that, repeatedly, with the women in his life. It’s not just his mother, but her and then, also, Jeannine, the woman that he goes on a date with. He’s trying to connect and be vulnerable in that connection.

Mr. Almond: He says to Karen, “Do you ever miss it? Do you ever miss the hospital?” And she’s faking, and she says, “No.” And he says, “But that was where we had the laughs.” And she says, “But that was a hospital.” In other words, “You’re sick, and we were sick, and I’m not that anymore. I’m putting on a thousand clowns. I’m over it.” And of course, the devastating and pivotal moment in the film is when he tries to call her up again and discovers that she’s killed herself.

And that’s really what precipitates the big cathartic moment at the end. It’s this lesson that human beings keep having to learn, over and over again: If you deny a truth inside you, it is somehow gonna distort itself into evil and self-destruction within your life and within your relationships.

And you’re absolutely right that this relationship with Jeannine Pratt is crucial for him. In its way, she is part of his healing process — but it’s not the centerpiece of the film. It’s really a film about a family that cannot stay together, because the grief that all the members of the family are experiencing around this loss are too devastating.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

Ms. Percy: So you mentioned this, early in our conversation, that this is a movie that you continue to watch, throughout your life, and it always continues to give you more. And I just wonder if you could expand on that — how this movie has continued to change for you as you’ve gotten older; and the more you’ve watched it, how you’ve grown together.

Mr. Almond: Well, I will say that part of what my routine was, growing up, even though I was probably, in a sense, the weakest and most anxious of the brothers — or maybe I was the most anxious and, therefore, in some way I felt the weakest, but the fact that I was able to get into therapy as a kid, and I’ve done a lot since then — those are all moments, in the end, of strength. I’ve said outright, on the podcast and in life, not everybody’s gonna get therapy. Not everybody wants it, not everybody can afford it, but everybody deserves it, to have a place you can go where you can get to the bottom of it, go back to the beginning of it and get to the bottom of it.

And I think that process is so widely maligned and shamed and misunderstood, and I think it’s been overtaken by antidepressants and psychopharmacology. But there really is nothing like, in my experience, that process of talking with somebody whose sole job is to listen to the story of your life and help you make sense of it. And I think, in a sense, the film is so devastatingly precise about how people try to connect and fail to connect, or how people connect but can only go so deep with one another. And when a big, traumatic event disrupts people’s lives, some people can kind of arise from the ashes and really still lead a fully emotional life and get over it and forgive themselves and forgive the person who’s died; but other people really can’t.

And that is just true of how life is. And the longer I’ve been alive, the more I see that it’s a real struggle, to examine your life. I think Socrates talks about the “examined life,” but that lets you in for a lot of sorrow, if you really are determined to do that work. I think it makes your life more meaningful, but as Dr. Berger said, “It hurts to feel. It’s not gonna tickle; it’s gonna hurt.”

Ms. Percy: I love that line. “A little advice about feeling, kiddo. Don’t expect it always to tickle.”

Mr. Almond: It’s funny; I watch the film all the time, and I kind of have to be careful about it, because I get so emotional. I almost immediately start crying. And I watched it, maybe five or seven years ago, with a whole bunch of people. And the person who wanted to watch it was my friend Chris Castellani — he’s another amazing, brilliant novelist who lives here in Boston. And he said to me, “We’re having an Ordinary People party. I want to show the film.” And I was like, “Chris, you have no idea how deeply into your party I am.”

And it was fascinating, Lily, the reaction, because the reaction was — there were like seven or eight people watching the film. And like six of them were watching, and they were definitely feeling it, but they were kind of like, “Yeah, this is — it’s a film; it’s kind of an older film. I see it’s well-made, it’s well-crafted, it’s pretty intense.” And Chris and I were bawling our eyes out. We’re literally sobbing, quietly trying to keep it together. And I think maybe artists and writers are particularly vulnerable to this film, because it is a film about how you can only — that the only way to really lead a full and meaningful life is to tell the truth, even and especially when that’s painful.

And I think part of the contract of being a writer or an artist of any kind is that you’re at least trying to do that work. You’re trying to get to unbearable feeling. You’re trying to engage with productive bewilderment. What do we do in the face of loss? What do we do around the limits of our ability to love effectively in the world? What do we do when somebody is taken from us, and we can’t get over it? These questions that are really at the center of most art and are really, essentially, the form of bewilderment that art was intended to — not solve for us but help us feel less alone with.

[excerpt: “Ordinary People”]

[music: “Canon in D” by Johann Pachelbel, arranged by Jean-François Paillard, from Ordinary People: Original Soundtrack]

Ms. Percy: Steve Almond is the co-host of one of my all-time favorite podcasts, Dear Sugars. He is also one of the most prolific and beautiful writers around. His latest book is called Bad Stories: What the here Just Happened to Our Country. To find out where you can buy it, and for all your Steve Almond goodness, go to stevealmondjoy.org.

Next time, we’re going to be talking about the lovely Steve Carell movie, Dan in Real Life, a movie that I love and watch whenever I need a warm hug and can’t find a human nearby to give it to me. If you want to check that movie out before the conversation, you’ve got two weeks and can currently find it streaming on Amazon Video, iTunes, GooglePlay, YouTube, and Vudu.

This Movie Changed Me is produced by Maia Tarrell, Chris Heagle, Marie Sambilay, and Tony Liu, and is an On Being Studios production. Subscribe to us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts, and if you’re feeling friendly, leave us a review. We’ve loved reading what’s been posted thus far, and we promise that we take your thoughtful feedback into account. A special shout-out to username Midas Welby DDS — we heard you. As much as I love him, I’m no longer going to mention Mr. Rogers every episode.

I’m Lily Percy, be kind to yourself, and go watch a movie that makes you feel seen.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.